Patrick Hamilton (martyr)

Patrick Hamilton | |

|---|---|

Patrick Hamilton by John Scougal, c. 1645-1730. This is the only known portrait of the martyr. | |

| Born | c. 1504 |

| Died | 29 February 1528 |

| Occupation(s) | churchman and Reformer |

Patrick Hamilton (1504 – 29 February 1528) was a Scottish churchman and an early Protestant Reformer in Scotland. He travelled to Europe, where he met several of the leading reformed thinkers, before returning to Scotland to preach. He was tried as a heretic by Archbishop James Beaton, found guilty and handed over to secular authorities to be burnt at the stake in St Andrews.

Early life

He was the second son of Sir Patrick Hamilton of Kincavil and Catherine Stewart, daughter of Alexander, Duke of Albany, second son of James II of Scotland. He was born in the diocese of Glasgow, probably at his father's estate of Stanehouse in Lanarkshire, and was most likely educated at Linlithgow. In 1517 he was appointed titular Abbot of Fearn Abbey, Ross-shire. The income from this position paid for him to study at the University of Paris, where he became a Master of the Arts in 1520.[1] It was in Paris, where Martin Luther's writings were already exciting much discussion, that he first learnt the doctrines he would later uphold. According to sixteenth century theologian Alexander Ales, Hamilton subsequently went to Leuven, attracted probably by the fame of Erasmus, who in 1521 had his headquarters there.[2]

Return and flight

Returning to Scotland, Hamilton selected St Andrews, the Scottish capital of the church and of learning, as his residence. On 9 June 1523 he became a member of St Leonard's College, part of the University of St Andrews, and on 3 October 1524 he was admitted to its faculty of arts, where he was first a student of, and then a colleague of the humanist and logician John Mair. At the university Hamilton attained such influence that he was permitted to conduct, as precentor, a musical mass of his own composition in the cathedral.[3]

The reforming doctrines had now obtained a firm hold on the young abbot, and he was eager to communicate them to his fellow-countrymen.[4] Early in 1527 the attention of James Beaton, Archbishop of St Andrews, was directed to the heretical preaching of the young priest, whereupon he ordered that Hamilton should be formally tried. Hamilton fled to Germany, enrolling himself as a student, under Franz Lambert of Avignon, in the new University of Marburg, opened on 30 May 1527 by Philip of Hesse. Among those he met there were Hermann von dem Busche, one of the contributors to the Epistolæ Obscurorum Virorum, John Frith and William Tyndale.[2]

Late in the autumn of 1527 Hamilton returned to Scotland, living up to his convictions. He went first to his brother's house at Kincavel, near Linlithgow, where he preached frequently, and soon afterwards he married a young lady of noble rank; her name is unrecorded. David Beaton, the Abbot of Arbroath, avoiding open violence through fear of Hamilton's high connections, invited him to a conference at St Andrews.[5] The reformer, predicting that he was going to "confirm the pious in the true doctrine" by his death,[2] accepted the invitation, and for nearly a month was allowed to preach and dispute.[2]

With the publication of Patrick's Places[6] in 1528, he introduced into Scottish theology Martin Luther's emphasis of the distinction of Law and Gospel.[7]

Trial and execution

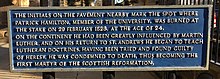

At length, he was summoned before a council of bishops and clergy presided over by the archbishop. There were thirteen charges, seven based on the doctrines affirmed in Philip Melanchthon's Loci Communes, the first theological exposition of Martin Luther's scriptural study and teachings in 1521. On examination Hamilton maintained their truth, and the council condemned him as a heretic on all thirteen charges. Hamilton was seized, and, it is said, surrendered to the soldiery on an assurance that he would be restored to his friends without injury.[2] However, the council convicted him, after a sham disputation with Friar Campbell, and handed him over to the secular power, to be burnt at the stake as a heretic, outside the front entrance to St Salvator's Chapel in St Andrews. The sentence was carried out on the same day to preclude any attempted rescue by friends. He burnt from noon to 6 p.m.. His last words were "Lord Jesus, receive my spirit".[8] The spot is today marked with a monogram of his initials set into the cobblestones of the pavement of North Street.

His courageous bearing attracted more attention than ever to the doctrines for which he suffered, and greatly helped to spread the Reformation in Scotland. It was said that the "reek of Master Patrick Hamilton infected as many as it blew upon".[9] His fortitude during martyrdom won over Alexander Ales, who had been appointed to convince Hamilton of his errors, to the Lutheran cause.[10] His martyrdom is unusual in that he was almost alone in Scotland during the Lutheran stage of the Reformation. His only known writings, based upon Loci communes and known as "Patrick's Places", echoed the doctrine of justification by faith and the contrast between the gospel and the law in a series of clear-cut propositions.'"Patrickes Places"' was not Hamilton's own title, but was given in the translation into English by John Fryth in 1564, and are presented in Book 8 of the 1570 edition of John Foxe's "Acts and Monuments".[2].

Students at the University of St Andrews traditionally avoid stepping on the monogram of Hamilton's initials outside St Salvator's Chapel for fear of being cursed and failing their final exams. To lift the curse students may participate in the annual May dip where they traditionally run into the North Sea at 05.00 to wash away their sins and bad luck.

A school in Auckland, New Zealand called 'Saint Kentigern College' has a house named after Patrick Hamilton

Katherine Hamilton

Patrick's sister, Katherine Hamilton, was the wife of the Captain of Dunbar Castle and also a committed Protestant. In March 1539 she was forced in exile to Berwick upon Tweed for her beliefs. She had been in England before and met the Queen, Jane Seymour.[11]

According to the historian John Spottiswood, Katherine was brought to trial for heresy before James V at Holyroodhouse in 1534, and her other brother James Hamilton of Livingston fled. The King was impressed by her conviction shown in her short answer to the prosecutor. He laughed and spoke to her privately, convincing her to abandon her profession of faith. The other accused also recanted for the time.[12]

Bibliography

For a more extensive bibliography see George M. Ella's book review.[13]

Mackay's bibliography:

- Knox's Hist, of the Reformation ;

- Buchanan and Lindsay of Pitscottie's Histories of Scotland ;

- the writings of Alexander Alesius and the records of St. Andrews and Paris are the original authorities ;

- Life of Patrick Hamilton, by the Rev. Peter Lorimer, 1857, to which this article is much indebted ;

- Patrick Hamilton, a poem by T. B. Johnston of Cairnie, 1873

- Rainer Haas, Franz Lambert und Patrick Hamilton in ihrer Bedeutung für die Evangelische Bewegung auf den Britischen Inseln, Marburg (theses) 1973

- The most recent biography in almost 100 years Patrick Hamilton – The Stephen of Scotland (1504-1528): The First Preacher and Martyr of the Scottish Reformation, by Joe R. D. Carvalho, AD Publications, Dundee 2009.

See also

References

- Citations

- ^ Dallmann 1918, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e Chisholm 1911, p. 887. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFChisholm1911 (help)

- ^ Lorimer 1857.

- ^ M'Crie 1905, p. 32-34.

- ^ Lorimer 1857, p. 139.

- ^ Patrick`s Places (1528)[1]

- ^ Wiedermann 1984, p. 17-20.

- ^ Tjernagel 2015, p. 6.

- ^ Mitchell 1900, p. 34.

- ^ Jacobs & Jacobs 1899, p. 212.

- ^ State Papers Henry VIII, vol. 5 part 4 cont. (1836), p.155 & note

- ^ Spottiswood, John, The History of the Church of Scotland, (1668), Bk. 2, pp.65-66

- ^ Ella 2009c.

- Sources

- Anderson, William (1877). "Patrick Hamilton of Kincavel". The Scottish nation: or, The surnames, families, literature, honours, and biographical history of the people of Scotland. Vol. 2. A. Fullarton & co. p. 427.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Barnett, T. Ratcliffe (1915). The makers of the kirk. London, Edinburgh, Boston: T. N. Foulis. pp. 63–68. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Beveridge, William (1908). Makers of the Scottish church. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark. pp. 73–84. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cameron, James K. (1984). Aspects of the Lutheran contribution to the Scottish Reformation. Scottish Church History Society. pp. 1–12. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carslaw, William Henderson (1907). Six martyrs of the Scottish reformation (includes Patrick's Places). Paisley: A. Gardner, publisher by appointment to the late Queen Victoria. pp. 9–30, 183–191. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Hamilton, Patrick". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Dallmann, William (1918). Patrick Hamilton: The First Lutheran Preacher and Martyr of Scotland. Retrieved 3 January 2008.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ella, George M. (2009c). Patrick Hamilton: The Stephen of Scotland. The First Preacher and Martyr of the Scottish Reformation, AD Publications, Dundee, 2009 By Joe Carvalho. Book Review. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fischer, Ernst Ludwig (1902). The Scots in Germany : being a contribution towards the history of the Scots abroad. Edinburgh: Otto Schulze & Co. pp. 163–165. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fleming, David Hay (1887). The Martyrs and Confessors of St. Andrews. Cupar: "Fife Herald" Office. pp. 28–69. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fleming, David Hay (1910). The Reformation in Scotland : causes, characteristics, consequences. London: Hodder and Stoughton. pp. 185–190. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Foxe, John (1837). "The Condemnation of Master George Wisehart". In Cattley, Stephen Reed (ed.). The acts and monuments of John Foxe: a new and complete edition. Vol. 8. London: R. B. Seeley and W. Burnside. pp. 625–636. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Grub, George (1861). An ecclesiastical history of Scotland: from the introduction of Christianity to the present time. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. pp. 8–13. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Howie, John; Carslaw, W. H. (1870). "Patrick Hamilton". The Scots worthies. Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson, & Ferrier. pp. 11–17.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Irving, Joseph (1881). The book of Scotsmen eminent for achievements in arms and arts, church and state, law, legislation, and literature, commerce, science, travel, and philanthropy. Paisley: A. Gardner. pp. 200–201. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Jacobs, Henry Eyster (1899). "Hamilton, Patrick". The Lutheran cyclopedia. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 212. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Keith, Robert (1844). History of the affairs of church and state in Scotland, from the beginning of the reformation to the year 1568. By Robert Keith...with biographical sketch, notes, and index, by the editor. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: The Spottiswoode Society. pp. 13–16, 329–332. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kidd, James (1885). "Patrick Hamilton and George Wishart". The Reformers: lectures delivered in St. James' Church, Paisley. Glasgow: J. Maclehose & Sons. pp. 344–379. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Knox, John (1949a). Dickinson, William Croft (ed.). History of the Reformation in Scotland. Vol. 1. London: Thomas Nelson and Son Ltd. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Knox, John (1949b). Dickinson, William Croft (ed.). History of the Reformation in Scotland. Vol. 2. London: Thomas Nelson and Son Ltd. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lorimer, Peter (1857). Patrick Hamilton, the First Preacher and Martyr of the Scottish Reformation. Edinburgh: Thomas Constable.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lorimer, Peter (1860). The Scottish Reformation : a historical sketch. London & Glasgow: Ricahrd Griffin & co. pp. 6–17. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - MacIntosh, J. S. (1884). The breakers of the yoke : sketches and studies of the men and scenes of the Reformation. Philadelphia: Henry B. Ashmead. pp. 194–212. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mackay, Aeneas James George (1885–1900). "Hamilton, Patrick". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - M'Crie, Thomas (1905). Life of John Knox : containing illustrations of the history of the Reformation in Scotland. Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath-school work. pp. 32–34. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Merle d'Aubigné, J. H. (1877). History of the reformation in Europe in the time of Calvin. Vol. 6. Translated by Cates, William L. B. New York: Robert Carter & brothers. pp. 12–70. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Merle d'Aubigné, J. H.; Bulkley, Charles Henry Augustus (1882). D'Aubigné's Martyrs of the reformation. Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication. pp. 363–418. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mitchell, Alexander Ferrier (1900). "Patrick Hamilton". In Fleming, David Hay (ed.). The Scottish Reformation: Its Epochs, Episodes, Leaders and Distinctive Characteristics (Being the Baird Lecture for 1899). Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons. pp. 19–33.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Muller, Gerhard (1985). Protestant theology in Scotland and Germany in the early days of the reformation. Scottish Church History Society. pp. 103–117. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shaw, Duncan (1985). Zwinglian influences on the Scottish Reformation. Scottish Church History Society. pp. 119–139. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thomson, J. H.; Hutchison, Matthew (1903). The martyr graves of Scotland. Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson & Ferrier. pp. 210–211. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tjernagel, Neelak S (2015). "Patrick Hamilton: Precursor of the Reformation in Scotland". Retrieved 11 October 2007.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wiedermann, Gotthelf (1984). "Martin Luther versus John Fisher; some ideas concerning the debate on Lutheran theology at the University of St Andrews 1525-30". Scottish Church History Society. pp. 13–34. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Hamilton, Patrick". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- 1504 births

- 1528 deaths

- People executed for heresy

- Executed Scottish people

- Alumni of the University of St Andrews

- University of Paris alumni

- 16th-century Scottish clergy

- Scottish abbots

- 16th-century Protestant religious leaders

- 16th-century Protestant martyrs

- People from Linlithgow

- People from South Lanarkshire

- People executed by the Kingdom of Scotland by burning

- 16th-century executions by Scotland

- Scottish Reformation

- Protestant martyrs of Scotland