Hallidie Plaza

| Hallidie Plaza | |

|---|---|

View east in East Hallidie Plaza in 2020 | |

| Location | Union Square |

| Nearest city | San Francisco |

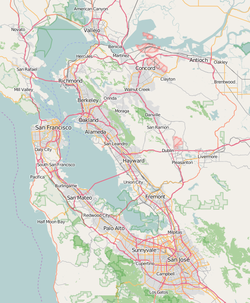

| Coordinates | 37°47′4″N 122°24′29″W / 37.78444°N 122.40806°W |

| Created | 1973 |

| Designer | |

| Public transit access | Muni Metro/BART (Powell Street) |

Hallidie Plaza is a public square located at the entrance to Powell Street Station (the third-busiest BART station as of 2015[1]) on Market Street in the Union Square area of downtown San Francisco, California, United States. Hallidie Plaza was designed jointly by Lawrence Halprin, John Carl Warnecke, and Mario Ciampi and opened in 1973.[2] In 1997, a perforated stainless steel-screened elevator was added to provide access to the plaza and station for disabled people.

Although Powell Street station is one of the busiest stations in the BART system, Hallidie Plaza is relatively underused and has been criticized for its isolation from Market.

Location and history

Hallidie Plaza lies within the triangular block bounded by Market, Mason, and Eddy, north of Market;[2] the plaza is below grade, crossed by a bridge carrying Cyril Magnin/5th which divides the plaza into eastern and western parts. The western part receives relatively little use.[3][4]

It is just south of the Flood Building, One Powell Street, and the cable car turntable at Powell and Market streets,[5] and lies across Market from the Westfield San Francisco Centre mall. Hallidie Plaza also includes the Powell Street mall, which is the one-block-long portion of Powell south of Eddy that has been closed to road traffic.[6]: 4–62

Concept and design

After San Francisco Bay Area voters approved the creation of the Bay Area Rapid Transit District in 1962, the report What to Do About Market Street was published later that year. In it, Halprin and Associates, led by landscape architect Lawrence Halprin, called for pedestrian arcades to connect the planned transit station with parking garages, north or south of Market, in this retail district.[7]: 31

Two potential sites were examined in the 1965 Market Street Design Report, written by the firms led by Mario J. Ciampi and John Carl Warnecke; one site was the triangular block eventually selected, bounded by Mason, Eddy, and Market; the other site was south of Market across from the Phelan Building.[8] By 1967, Ciampi and Warnecke had refined the design for the planned Powell Station Plaza; the 1967 site and design largely matched the eventual implementation of Hallidie Plaza, a sunken triangular plaza with escalators parallel to Market Street at the eastern and western ends. However, the 1967 plan called for more gradual amphitheater-style steps leading north to street level.[9]

The three architecture firms formed the Market Street Joint Venture Architects in 1968 to take on the Market Street Redevelopment Project in 1968, which also encompassed the design for two other large plazas along Market: United Nations Plaza at the neighboring Civic Center/UN Plaza station and Embarcadero Plaza near the San Francisco Ferry Building.[6]: 4–30

Hallidie Plaza opened in 1973, as a central element of a remodeling of Market Street spurred by BART reconstruction after the double-deck Market Street Subway tunnel was built using cut-and-cover construction.[4] It was named after Andrew Smith Hallidie, who developed the world's first cable car system in 1873.[4][10]

Mr. Halprin has created, along Market Street, not only a cluster of places but a cluster of kinetic, human-scale experiences which make it architecture.

— William Marlin, The Architectural Forum (April 1973)[11]

As built, the plaza sits 20 feet (6.1 m) below street level, built with granite walls, terraced concrete planters and brick paving laid in a herringbone pattern, extending into a walkway underneath Cyril Magnin Street.[1] Mezzanine levels are provided on both the eastern and western portions of the plaza, and wood slat benches were originally installed on the lower and mezzanine levels of the plaza. In addition to the eastern and western escalators, the plaza can be accessed from street level via stairs in both portions, parallel to Cyril Magnin/5th.[6]: 4–62 The plaza also contained a 1,880 sq ft (175 m2) visitor information center off the tunnel under Cyril Magnin/5th[12] from 1976 until it moved to Moscone Center at the end of 2018.[13]

Updates

Construction of an elevator started in 1997; Michael Willis was the architect responsible for the perforated metal design.[14] The $510,000 elevator was approved after a lawsuit from disability rights activists charged that Hallidie Plaza was not accessible. The San Francisco Arts Commission was involved in the approval process, and took the opportunity to create a new public sculpture.[15]

During the administration of Mayor Willie Brown, more frequent police patrols initially displaced homeless residents from Civic Center Plaza to UN Plaza and Hallidie Plaza;[16] a committee of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors voted to bring the latter two under the city's Parks code which would allow stricter enforcement of laws criminalizing vagrancy;[17][18] the full Board passed the measure in late January 1999.[19] John King noted that making the plazas more unwelcoming did not discourage the homeless from gathering and recommended instead "the city should strive for places that are vibrant and attract all walks of life."[20] Indeed, after Cable Car Coffee opened up a branch location in Hallidie Plaza in June 1998, the increase in retail activity depressed the number of homeless in the plaza.[21] The wood slat benches were removed in 1998, along with trees along the northeastern edge.[4]

In 2003, the mezzanine terrace was closed after reports of criminal activity;[22] the benches were removed and the terrace was reopened in 2005.[10]

In 2009, it was proposed to close the western part of the plaza; the area west of 5th/Cyril Magnin would be covered and a 480,000 US gal (1,800,000 L) cistern would be installed in the below-grade space, while the new deck would be used for cafe seating and public performances. The cistern would be used to hold groundwater pumped from Powell Street station; the station requires continuous pumping to prevent flooding from underground creeks.[3]

The city kicked off the Better Market Street project in 2012, aimed at improving the appeal of Market for the first time since the Market Street Redevelopment Plan was completed in the 1970s.[23] The Union Square Business Improvement District (USBID) released its Public Realm Design Manual in 2015, including a section entitled "Activating Hallidie Plaza" with suggestions to improve the site's usability and attract retail development.[24]

A sign with the names and distances to the nineteen sister cities of San Francisco was installed at Hallidie Plaza in late June 2018.[25] USBID has studied the possibility of adding flags of the sister cities to Hallidie Plaza and installing the large sculpture R-Evolution by Marco Cochrane to attract more activity.[26][27]

Reception

San Francisco Chronicle urban design critic John King has described Hallidie Plaza as desolated, denounced its design as deeply flawed, and commented that "what was envisioned as a grand entrance instead is a void to avoid, a deep, angled space beloved by none but too pricey to fix."[1] King also said the plaza was "flawed from the start, products of a 1960s-era planning mentality that says spaces work best when they're kept apart from traffic and noise."[20] In contrast, architect Lajos Héder said the contrast created by the "technologically oriented BART environment [opening] directly onto the visual and social complexity of the San Francisco street scene ... has a genuine aesthetic value that transcends that of many more harmoniously integrated situations. It is a piece of powerful urban theater, by virtue of the impressions and lessons imparted by its contrasts."[28]

Clare Cooper Marcus faulted the lack of interesting features and the dramatic difference in elevation for its paucity of users: "At Hallidie Plaza in San Francisco, there is little to look at beyond a large expanse of brick paving, glaring granite walls (on a hot day it is like an oven), small trees that offer no shade, and colorless planters. ... It is little wonder that the seats at the intermediate and upper levels, where passersby and traffic on Market Street create some interest, are always more heavily used than are those in the sunken plaza areas."[29]

Hank Donat called the metal-screened elevator added in 1997 "San Francisco's Poop Chute", describing it as "a hideous and cold addition to the open plaza."[30] On April 30, 2018, BART started a pilot program to provide elevator attendants to discourage drug use and the elimination of human waste in the elevators at Powell Street and Civic Center/UN Plaza.[31] The pilot was expanded to the other two downtown BART stations in 2019.[32]

References

- ^ a b c King, John (November 11, 2015). "Sunken Hallidie Plaza was a deeply wrong design idea". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- ^ a b King, John (August 16, 2014). "Spoilers: Eyesore buildings that taint their environment". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- ^ a b Gordon, Rachel (December 2, 2009). "Ideas for Hallidie Plaza include reservoir". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d King, John (February 2, 2006). "Just start over with desolate Hallidie Plaza". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ King, John (March 10, 2005). "Attention shoppers -- This building is a beautifully restored piece of history". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ a b c ICF (November 2016). Cultural Landscape Evaluation, Better Market Street Project (PDF) (Report). Final. San Francisco Department of Public Works. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- ^ Halprin, Lawrence; Carter, Donald Ray; Rockrise, George T. (1962). "The Look of Market Street". What to Do About Market Street: A prospectus for a development program prepared for the Market Street Development Project, an associate of SPUR: The San Francisco Planning and Urban Renewal Association (Report). Livingston and Blayney, City and Regional Planners. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ Mario J. Ciampi & Associates, Architects & Urban Consultants; John Carl Warnecke & Associates, Architects & Planning Consultants (23 June 1965). Market Street design report number 2 – Subway Entrance Plazas (Report). City and County of San Francisco. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ Warnecke, John Carl; Ciampi, Mario (1967). Market Street design plan: summary report (Report). Department of City Planning, San Francisco. Retrieved 5 October 2018.

- ^ a b Pullen, Suzanne (July 14, 2005). "CHRONICLEWATCH Results / Working for a better Bay Area". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ Marlin, William (April 1973). "San Francisco: The Streets of Camelot" (PDF). Architectural Forum. Vol. 138, no. 3. Billboard. p. 34. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ "Visitor Information Center FAQ". San Francisco Travel. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- ^ Li, Roland (July 20, 2018). "San Francisco's visitor center moving from Powell area to Moscone Center". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ Adams, Gerald D. (April 12, 1997). "Elevator will go to Hallidie Plaza". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ Matier, Philip; Ross, Andrew; Marinucci, Carla (October 13, 1997). "MATIER & ROSS -- That's Not Just an Elevator, It's Public Sculpture, S.F. Style". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ Gordon, Rachel (January 12, 1999). "U.N. Hallidie plazas next for S.F. homeless sweeps". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ Epstein, Edward (January 21, 1999). "Crackdown on Homeless Extended to Hallidie, U.N. Plazas / Proposal would put areas under city's park code". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ Gordon, Rachel (January 21, 1999). "New crackdown on city's homeless". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ Epstein, Edward (January 26, 1999). "More Ground Pulled From Under S.F. Homeless / Union Square spruce-up approved, crackdown in U.N., Hallidie plazas". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ a b King, John (March 10, 2002). "Common ground / By shooing vagrants, S.F. plazas have gone from bad to worse -- now planners plead for city to put out the welcome mat". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ Epstein, Edward (September 8, 1998). "Proposal to Roust Homeless From Downtown Plazas / Foe says S.F. supervisor's suggestion is re-election ploy". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ Pullen, Suzanne (October 5, 2003). "ChronicleWatch: Working for a better Bay Area". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ Wildermuth, John (September 16, 2012). "SF Market Street up for a face-lift". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ RHAA (April 17, 2015). "4.02 Activating Hallidie Plaza". Public Realm Design Manual (PDF) (Report). Union Square Business Improvement District. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ Costley, Drew (July 2, 2018). "San Francisco's 19 sister cities get new sign in Hallidie Plaza. Do you know them all?". SFGate. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ "Hallidie Plaza". Union Square Foundation. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ Union Square Business Improvement District Executive Committee Meeting (PDF) (Report). Union Square Business Improvement District. October 24, 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ Héder, Lajos; Shoshkes, Ellen (November 1980). "Facility Design: Rapid Transit | Case Study 2.5b – BART, A High Technology System". Aesthetics in Transportation: Guidelies for Incorporating Design, Art and Architecture Into Transportation Facilities (Report). Washington DC: U.S. Department of Transportation. pp. 131–132. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ Marcus, Clare Cooper; Francis, Carolyn; Russell, Robert (1998). "1. Urban Plazas". In Marcus, Clare Cooper; Francis, Carolyn (eds.). People Places: Design Guidelines for Urban Open Space (Second ed.). New York City: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 46–47. ISBN 0-471-28833-0. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ Donat, Hank (2005). "Wall of Infamy". Mister SF. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ Rodriguez, Joe Fitzgerald (April 30, 2018). "BART and Muni elevator attendants shoo away urinators, drug users". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- ^ McFarland, Cody (November 6, 2019). "Attendant program keeping BART elevators safe, clean expands to two more downtown stations". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

External links

- Ho-hum Hallidie Video commentary by John King (2015)