Propaganda during the Reformation

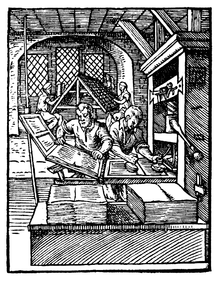

Propaganda during the Reformation, helped by the spread of the printing press throughout Europe and in particular within Germany, caused new ideas, thoughts, and doctrine to be made available to the public in ways that had never been seen before the sixteenth century. The printing press was invented in approximately 1450 and quickly spread to other major cities around Europe; by the time the Reformation was underway in 1517 there were printing centers in over 200 of the major European cities.[1][2] These centers became the primary producers of Reformation works by the Protestants, and in some cases Counter-Reformation works put forth by the Roman Catholics.

Printed texts and pamphlets

| Reformation-era literature |

|---|

There were a number of different methods of propaganda used during the Reformation including pamphlets/leaflets, texts, letters, and translations of the Bible/New Testament. Pamphlets or leaflets were one of the most common forms of propaganda, usually consisting of about eight to sixteen pages – were relatively small and easy to conceal from the authorities. This made them very useful to reformers whose ideas were not accepted by the Roman Catholic authorities. The majority of these pamphlets promoted the Reformation and the Protestant ideas; however pamphlets were also used by Roman Catholic propagandists, but not to the same effect.[3]

Protestant and Roman Catholic propaganda during the Reformation attempted to sway the public into adopting or continuing religious practices. Propagandists from both groups attempted to publish documents about church doctrine, to either retain their believers or influence new believers. Occasionally these printed texts also acted as manuals for lay people to refer to about the appropriate way to conduct themselves within the church and society.

Printed texts and pamphlets were available to a large number of literate people, at a relatively affordable price. Furthermore, the ideas and beliefs of the reform writers, including Martin Luther, were also widely disseminated orally to large numbers of illiterate people who may not have been involved with the Reformation otherwise.[3] The Roman Catholic propagandists also utilized this method of propaganda within the church but it was not as effective as the Protestant propagandists.

Protestant propaganda

Protestant propaganda and church doctrine broke away from the traditional conventions of the Catholic Church. They called for a change in the way that the church was run and insisted that the buying and selling of indulgences and religious positions be stopped as well as the papal corruption that had been allowed to occur.[9][10][11][12] In addition to this, Reformers questioned the authority of the Church and in particular the Pope. Protestants believed that the main authority of their church should be the Gospel or Scripture (expounded by private interpretation) and not the Pope, who is the earthly head of the Catholic Church.[13]

Another dominant message that was found in Protestant propaganda was the idea that every person should be granted access to the Bible to interpret it for themselves; this was the primary reason why Luther translated and published numerous copies of the New Testament during the Reformation years.[13] Protestants questioned the belief that the Pope had the sole authority to interpret scripture. This can be seen in Luther’s publication titled To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, which criticized the Catholic belief that the Pope was supreme and could interpret scripture however he saw fit.[14] To combat this, Luther put forth arguments from the Bible that indicated that everyone had the ability to interpret scripture and not just the Pope.

In terms of tone and style, Reformation propaganda, while sometimes serious in tone, was often satirical, featuring word-play and sarcasm. In this it developed earlier medieval traditions of religious satire.[15][16] One example of this would be Martin Luther's commentary on the Life of John Chrysostom in his Die Lügend von S. Johanne Chrysostomo.

The Reformation messages were very controversial and were frequently banned in a number of Catholic cities.[17] Despite this attempt by the Catholic Church to contain and repress Protestant propaganda, the Protestant propagandists found effective ways of disseminating their messages to their believers. The use of pamphlets became the primary method of spreading Protestant ideas and doctrine. Pamphlets took little time to produce and they could be printed and sold quickly making them harder to track down by the authorities and thus making them a very effective method of propaganda. The sheer number of pamphlets produced during this time period indicates that Protestant works during the Reformation were available on a consistent basis and on a large scale, making the controversial ideas accessible to the masses. This is one of the reasons that the Protestants were successful in their propaganda campaign and in the Reformation.[3]

Roman Catholic reaction to Protestant propaganda

The dissension of the Reformers was not welcomed by Roman Catholics who called this behaviour and the works of the Protestant Propagandists heretical.[18] They disagreed with the Protestant Reformers and the messages that they were presenting to the public. The majority of Roman Catholics believed that Church matters should not be discussed with lay people, but kept behind closed doors.[19] The majority of the works published by Roman Catholics were Counter-Reformational and reactive.[20]

Rather than publishing proactive works, the Catholic apologists would often refute Luther’s and other Protestants’ arguments after they had been published. An example of a reactive propaganda campaign publicized by Roman Catholics was with regards to the Peasants War of 1525. The propagandists blamed the Peasants War, and all the turmoil caused by it, on Luther. Many leading Roman Catholic writers believed that had Luther not written his heretical works, the violence caused by the Peasants War would not have occurred.[21] This can be seen in Hieronymus Emser’s work titled Answer to Luther’s “Abomination” Against the Holy Secret Prayer of the Mass, Also How, Where, and With Which Words Luther Urged, Wrote, and promoted Rebellion in his books published in Dresden in 1525.[22] Emser actually quoted Luther’s work in this article and in doing so inadvertently introduced Protestant ideas and doctrine to Roman Catholic readers who may not have had any prior exposure to them.[23]

Unlike the Protestants who targeted the masses through printed works in the vernacular of the people, Roman Catholic propagandists targeted influential people such as priests who preached to their congregations on a weekly basis. Thus with fewer works they reached large Catholic audiences.[24]

Although the Roman Catholic propagandists did put forth some effective propaganda campaigns, primarily the campaign against Luther regarding the Peasants War, they neglected to get their message across to the general public. They failed to capitalize in the ways that the Protestant propagandists were able to; they did not commonly produce works in the vernacular of the people, which had been an effective tactic for Protestants. Also Roman Catholic publications, either in German or Latin, produced during the reformation years were greatly outnumbered by the Protestants.[25] The sheer volume of Protestant publications made it impossible for the Roman Catholic propagandists to quell the Protestant ideas and doctrine that transformed religious thought and doctrine in the sixteenth century.

Leading propagandists during the Reformation

There were a number of Protestant reformers who played a role in the success of Protestant propaganda, such as Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt, Urbanus Rhegius, and Philipp Melanchthon. The single most influential person was Martin Luther.[26] Luther wrote much more than any other leading reformer, and the majority of his works were in the German vernacular. It is estimated that Luther's works had over 2200 printings (with re-printings) by 1530, and he continued to write until the time of his death in 1546.[27][28]

Luther's use of the language of the people was one of the primary ideas of the Reformation. He believed in the "Priesthood of All Believers", that every person was a priest in their own right and could take control of their own faith.[14] Of the total lifetime printings of Luther, estimated to be around 3183, 2645 were written in German and only 538 in Latin.[29] Luther's predominance meant that the Protestant propaganda campaign was cohesive, with a consistent and accessible message.

Luther produced other works: sermons, which were read in Churches around the Empire; translations of the Bible, primarily the New Testament written in German; doctrine on how to conduct oneself within the church and society; and a multitude of letters and treatises. Often Luther wrote in response to others who had criticized his works or asked for clarification or justification on an issue.[30][31] Three of Luther’s major treatises, written in 1520, are To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, On the Freedom of a Christian, and On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church; these works were significant documents for the Reformation as a whole.[32]

Catholic propagandists were not initially as successful as the Protestants were, but included several noteworthy figures: Johannes Cochlaeus, Hieronymus Emser, Georg Witzel, and John Eck who wrote in defense of Catholicism and against Luther and Protestantism.[33] They produced a combined total of 247 works.[33]

References

- ^ Edwards (1994), p. 15

- ^ Holborn (1942), p. 123

- ^ a b c Edwards (1994), p. 16

- ^ Oberman, Heiko Augustinus (1 January 1994). The Impact of the Reformation: Essays. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802807328 – via Google Books.

- ^ Luther's Last Battles: Politics And Polemics 1531-46 By Mark U. Edwards, Jr. Fortress Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-8006-3735-4

- ^ In Latin, the title reads "Hic oscula pedibus papae figuntur"

- ^ "Nicht Bapst: nicht schreck uns mit deim ban, Und sey nicht so zorniger man. Wir thun sonst ein gegen wehre, Und zeigen dirs Bel vedere"

- ^ Mark U. Edwards, Jr., Luther's Last Battles: Politics And Polemics 1531-46 (2004), p. 199

- ^ Bainton (1952), p. 5

- ^ Rupp & Drewery (1970a)

- ^ Taylor (2002), p. 98

- ^ Todd (1964), p. 282

- ^ a b Edwards (1994), p. 12

- ^ a b Rupp & Drewery (1970b)

- ^ Schenda (1974), p. 187 n. 19

- ^ Kalinke (1996), pp. 3–4

- ^ Taylor (2002), p. 101

- ^ Bainton (1952), p. 41

- ^ Edwards (1994), p. 31

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ Edwards (1994), p. 149

- ^ Emser (1525), quoted in Edwards (1994), p. 150.

- ^ Edwards (1994), p. 165

- ^ Edwards (1994), p. 38

- ^ Edwards (1994), p. 21

- ^ Edwards (1994), p. 26

- ^ Edwards (1994), p. 27

- ^ Todd (1964), p. 271

- ^ Edwards (1994), p. 20

- ^ Edwards (1994), pp. 7, 9, 27

- ^ Cole (1984), p. 327

- ^ Edwards (1994), p. 5

- ^ a b Edwards (1994), p. 36

Bibliography

- Bainton, Roland H. (1952). The Reformation of the Sixteenth Century. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cole, Richard G. (1984). "Reformation printers: unsung heroes". Sixteenth Century Journal. 15 (3): 327–339. doi:10.2307/2540767. JSTOR 2540767.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Crofts, Richard A. (1985). "Printing, reform and Catholic Reformation in Germany 1521–1545". Sixteenth Century Journal. 16 (3): 369–381. doi:10.2307/2540224. JSTOR 2540224.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Edwards, Mark U. (1994). Printing, Propaganda and Martin Luther. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Emser, Hieronymus (1525). Answer to Luther's "Abomination" Against the Holy Secret Prayer of the Mass, Also How, Where, and With Which Words Luther Urged, Wrote, and promoted Rebellion in his book. Dresden.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Encyclopedia Britannica, Counter-Reformation

- Holborn, Louise W. (1942). "Printing and the growth of the Protestant movement in Germany from 1517 to 1524". Church History. 11 (2): 123–137. doi:10.2307/3160291. JSTOR 3160291.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kalinke, Marianne E. (1996). The Book of Reykjahólar: the Last of the Great Medieval Legendaries. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rupp, E. G.; Drewery, Benjamin (1970a). "Martin Luther, 95 Theses, 1517". Martin Luther, Documents of Modern History. London: Edward Arnold. pp. 19–25.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rupp, E. G.; Drewery, Benjamin (1970b). "Martin Luther, To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, 1520". Martin Luther, Documents of Modern History. London: Edward Arnold. pp. 42–45.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schenda, Rudolf (1974). "Hieronymus Rauscher und die protestantisch-katholische Legendenpolemik". In Wolfgang Brückner (ed.). Volkserzählung und Reformation. Ein Handbuch zur Tradierung und Funktion von Erzählstoffen und Erzählliteratur im Protestantismus. Berlin: Erich Schmidt.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Taylor, Philip M. (2002). Munitions of the Mind: a History of Propaganda from the Ancient World to the Present Day. New York: Manchester University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Todd, John M. (1964). Martin Luther: a Biographical Study. London: Burns & Oates.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)