Armies of the Rus' principalities

The Medieval Russian army, from the foundation of Kievan Rus' till the reforms of Ivan the Terrible, can be roughly divided into the Kievan Rus' period, between the 9th to 13th century, mainly characterized by infantry armies of town militia that were supported by Druzhina cavalry; and the feudal period from 1240 to 1550, which was distinguished by cavalry armies of noble militia and their armed servants.

Before the Mongol invasion

Tribal militia formed the basis of the army in Kievan Rus'[1] until the tax reform of Olga of Kiev in the middle of the 10th century.[2] In the subsequent period, under Svyatoslav I of Kiev and Vladimir the Great, Druzhina played a dominant role.[3] It consisted of senior members – the boyars – along with the rank-and-file ‘youths’ ("otroki").

The regiments of city militia, raised by the decision of the Veche,[4] were formed in the 11th century. These regiments received weapons and horses for a campaign from the prince.

Tactics and equipment

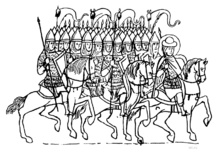

Before Mongol invasion of Rus' in the 13th century, a Prince would be accompanied by his Druzhina, a small retinue of heavy cavalry,[5] who would often fight dismounted (eq. Battle on the Ice). Massively heavy armor was used, mostly Scandinavian-style.[6] However, these squads, as a rule, did not exceed the number of several hundred men, and were unsuitable for united actions under a single command.[7]

At the same time, the main part of the Kievan Rus' army was the militia infantry. It was inferior to Druzhina in armament and the ability to own it. The militia used axes and hunting spears ("rogatina"). Swords were rarely used, and they had no armor other than plain clothes and fur hats.[5]

For the infantry, consisted of poorly armed peasants and tradesmen, numbers are uncertain. The only specific numbers mentioned for the Russians are 1.700 men of Evpaty Kolovrat [8](The Tale of the Destruction of Ryazan) and 3.000, men under Voivode Dorozh [9](Battle of the Sit River). However, these were exceptionally large numbers for Russian standards at the time. In 1242, Prince Alexander Nevski in Novgorod could muster no more than 1.000 Druzhina and 2.000 militia for the Battle on the Ice.[10] So, it is safe to estimate that, on average, a Russian Prince had hundreds of warriors in his retinue, rather than thousands.

Mongol invasions

After Mongol invasion of Rus' many independent principalities were destroyed. Remaining petty states were under growing pressure from Tatars, Sweden and Lithuania. Constant warfare precipitated the development of feudalism, and diminished the importance of the Veche.[11] The feudal militia, raised by the Boyars-landowners and individual Princes, came to replace popular militia. Princes (except in the Novgorod Republic) gathered and commanded the army.

In the second half of the 14th century, Druzhina was replaced by feudally organized units headed by Boyars or dependent Princes, and these units consisted of landed gentry (so called "Boyar's children" or "service people") and their armed servants ("military slaves"). In the 15th century, such organization of detachments replaced the city regiments.

Landed Army

The process of reforming the army was associated with the unification of the Russian lands in the 15th century. Gradually, the Grand Duchy of Moscow included new petty princedoms, courts of independent princes were dismissed, and "service people" passed to the Grand Duke. As a result, the vassal Princes and Boyars were transformed into state servants, who received estates for service in conditional holding (less often - in fiefdom). Thus, the "landed army" (Template:Lang-ru) was formed, the bulk of which were noblemen and "Boyar's children", with their armed slaves. This army organization would remain unchanged till 1550 (military reforms of Ivan the Terrible).

When the centralized state was formed, the people's militia was liquidated by the Grand Prince of Moscow. The prince called the masses to military service only in the event of serious military danger, regulating the extent and nature of this service at his own discretion.

Tactics and equipment

During the period of the Mongol invasions, Russia adopted much of Mongol military tactics and organization. While militia infantry still existed, they were, from XIV onward, mostly armed with ranged weapons, and delegated auxiliary duties, such as defending cities. The chronicles describe the Muscovites using arquebuses against the Tatars in 1480.[12] The men shooting these weapons were the forerunners of the Streltsy.[citation needed]

The bulk of the army were mounted archers,[12] who included Boyars, landed gentry ("Boyars' children") and armed slaves.

Under Tatar influence, the mail and lamellar armour of Kievan Rus' was replaced with brigandine ("Kuyak"), mail and plate ("Behterets") and mirror armour("Zertsalo"),[13] while poor noblemen and armed serfs wore long aketons ("Tyegilyai").

References

- ^ 1902-1960., Painter, Sidney (1953). A history of the Middle Ages, 284-1500. London: Macmillan. p. 71. ISBN 9780333043172. OCLC 216653180.

{{cite book}}:|last=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The Cambridge history of Russia. Perrie, Maureen, 1946-, Lieven, D. C. B., Suny, Ronald Grigor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2006. pp. 58. ISBN 9780521812276. OCLC 77011698.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ The Cambridge history of Russia. Perrie, Maureen, 1946-, Lieven, D. C. B., Suny, Ronald Grigor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2006. pp. 81. ISBN 9780521812276. OCLC 77011698.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ The Cambridge history of Russia. Perrie, Maureen, 1946-, Lieven, D. C. B., Suny, Ronald Grigor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2006. pp. 83. ISBN 9780521812276. OCLC 77011698.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Borisovich), Shirokorad, A. B. (Aleksandr; Борисович), Широкорад, А. Б. (Александр (2004). Rusʹ i Orda. Moskva: Veche. ISBN 5953302746. OCLC 56858783.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The Cambridge history of Russia. Perrie, Maureen, 1946-, Lieven, D. C. B., Suny, Ronald Grigor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2006. pp. 54. ISBN 9780521812276. OCLC 77011698.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Grigorʹevič., Hrustalev, Denis (2017). Rusʹ i mongolʹskoe našestvie : 20--50-e gg. XIII v. Sankt-Peterburg: Evraziâ. ISBN 9785918521427. OCLC 1003145949.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Никифоровская летопись. Никифорівський літопис. Том 35. Литовсько-білоруські літописи". litopys.org.ua. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- ^ "Новгородская летопись". krotov.info. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- ^ 1944-, Nicolle, David (1996). Lake Peipus 1242 : battle of the ice. London: Osprey Military. ISBN 9781855325531. OCLC 38550301.

{{cite book}}:|last=has numeric name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ The Cambridge history of Russia. Perrie, Maureen, 1946-, Lieven, D. C. B., Suny, Ronald Grigor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2006. ISBN 9780521812276. OCLC 77011698.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b The Cambridge history of Russia. Perrie, Maureen, 1946-, Lieven, D. C. B., Suny, Ronald Grigor. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2006. pp. 218. ISBN 9780521812276. OCLC 77011698.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "MEDIEVAL RUSSIAN ARMOR". www.xenophon-mil.org. Retrieved 2018-03-20.