Antitheatricality

Antitheatricality is any form of opposition or hostility to theater. Such opposition is as old as theater itself and can be found in all cultures [citation needed], suggesting a deep-seated ambivalence in human nature about the dramatic arts. Jonas Barish's 1981 book, The Antitheatrical Prejudice, was, according to one of his Berkeley colleagues, immediately recognized as having given intellectual and historical definition to a phenomenon which up to that point had been only dimly observed and understood. The book earned the American Theater Association's Barnard Hewitt Award for outstanding research in theater history.[1] Barish and some more recent commentators treat the anti-theatrical, not as an enemy to be overcome, but rather as an inevitable and valuable part of the theatrical dynamic.

Antitheatrical views have been based on philosophy, religion, morality, psychology, aesthetics and on simple prejudice. Opinions have focussed variously on the art form, the artistic content, the players, the lifestyle of theater people, and on the influence of theater on the behaviour and morals of individuals and society. Anti-theatrical sentiments have been expressed by government legislation, philosophers, artists, playwrights, religious representatives, communities, classes, and individuals.

The earliest documented objections to theatrical performance were made by Plato around 380 B.C. and re-emerged in various forms over the following 2,500 years. Plato's philosophical objection was that theatrical performance was inherently distanced from reality and therefore unworthy. Church leaders would rework this argument in a theological context. A later aesthetic variation, which led to closet drama, valued the play, but only as a book. From Victorian times, critics complained that self-aggrandizing actors and lavish stage settings were getting in the way of the play.

Plato's moral objections were echoed widely in Roman times, leading eventually to theater's decline. During the Middle Ages, theatrical performance gradually re-emerged, the mystery plays accepted as part of church life. From the 16th century onwards, once theater was re-established as an independent profession, concerns were regularly raised that the acting community was inherently corrupt and that acting had a destructive moral influence on both actors and audiences. These views were often expressed during the emergence of Protestant, Puritan and Evangelical movements.

Plato and ancient Greece

Athens

Around 400 B.C. the importance of Greek drama to ancient Greek culture was expressed by Aristophanes in his play, The Frogs, where the chorus leader says, "There is no function more noble than that of the god-touched Chorus teaching the city in song".[2] Theater and religious festivals were intimately connected.

Around 380 B.C. Plato became the first to challenge theater in the ancient world. Although his views expressed in The Republic were radical, they were aimed primarily at the concept of theater (and other mimetic arts). He did not encourage hostility towards the artists or their performances. For Plato, theater was philosophically undesirable, it was simply a lie. It was bad for society because it engaged the sympathies of the audience and so might make people less thoughtful. Furthermore, the representation of ignoble actions on the stage could lead the actors and the audience to behave badly themselves.[3]

Mimesis

Philosophically, acting is a special case of mimesis (μίμησις), which is the correspondence of art to the physical world understood as a model for beauty, truth, and the good. Plato explains this by using an illustration of an everyday object. First there is a universal truth, for example, the abstract concept of a bed. The carpenter who makes the bed creates an imperfect imitation of that concept in wood. The artist who paints a picture of the bed is making an imperfect imitation of the wooden bed. The artist is therefore several stages away from true reality and this is an undesirable state. Theater is likewise several stages from reality and therefore unworthy. The written words of a play can be considered more worthy since they can be understood directly by the mind and without the inevitable distortion caused by intermediaries.

Psychologically, mimesis is considered as formative, shaping the mind and causing the actor to become more like the person or object imitated. Actors should therefore only imitate people very much like themselves and then only when aspiring to virtue and avoiding anything base. Furthermore, they must not imitate women, or slaves, or villains, or madmen, or 'smiths or other artificers, or oarsmen, boatswains, or the like'.

Aristotle

In The Poetics (Περὶ ποιητικῆς) c. 335 BC, Aristotle argues against Plato’s objections to mimesis, supporting the concept of catharsis (cleansing) and affirms the human drive to imitate. Frequently, the term that Aristotle uses for ‘actor’ is prattontes, suggesting praxis or real action, as opposed to Plato’s use of hypocrites (ὑποκριτής) which suggests one who 'hides under a mask', is deceptive or expresses make-believe emotions. Aristotle wants to avoid the hypothetical consequence of Plato’s critique, namely the closing of theaters and the banishment of actors. Ultimately Aristotle’s attitude is ambivalent; he concedes that drama should be able to exist without actually being acted.[4]

Plutarch

The Moralia of Plutarch, written in the first century, contain an essay (often given the title, Were the Athenians More Famous in War or in Wisdom?) which reflects many of Plato's critical views but in a less nuanced way. Plutarch wonders what it tells us about the audience in that we take pleasure in watching an actor express strongly negative emotions on stage, whereas in real life, the opposite would be true.[5]: 34

Roman Empire and the rise of Christianity

Rome

Unlike Greece, theatre in Rome was distanced from religion and was largely led by professional actor-managers. From early days the acting profession was marginalised and, by the height of the Roman Empire, considered thoroughly disreputable. In the first century A.D., Cicero declared, "dramatic art and the theatre is generally disgraceful". During this time, permanent theater-building was forbidden and other popular entertainments often took theater's place. Actors, who were mainly foreigners, freedmen and slaves, had become a disenfranchised class. They were forbidden to leave the profession and were required to pass their employment on to their children.

Mimes included female performers, were heavily sexual in nature and often equated with prostitution. Attendance at such performances, says Barish, must have seemed to many Romans like visiting the brothels, "equally urgent, equally provocative of guilt, and hence equally in need of being scourged by a savage backlash of official disapproval".[5]: 38–43

Christian attitudes

Early Christian leaders, concerned to promote high ethical principles amongst the growing Christian community, were naturally opposed to the degenerate nature of contemporary Roman theatre. However, other arguments were also advanced.

In the second century, Tatian and later Tertullian, put forward ascetic principles. In De spectaculis, Tertullian argued that even moderate pleasure is to be avoided and that theater, with its large crowds and deliberately exciting performances, led to "mindless absorption in the imaginary fortunes of nonexistent characters". Absorbing Plato’s concept of mimesis into a Christian context, he also argued that acting was an ever-increasing system of falsifications. "First the actor falsifies his identity, and so compounds a deadly sin. If he impersonates someone vicious, he further compounds the sin." And if physical modification was required, say a man representing a woman, it was a "lie against our own faces, and an impious attempt to improve the works of the Creator".[5]: 44–49

In the fourth century, the famous preacher Chrysostom again stressed the ascetic theme. It was not pleasure but the opposite of pleasure that brought salvation. He wrote that "he who converses of theatres and actors does not benefit [his soul], but inflames it more, and renders it more careless... He who converses about hell incurs no dangers, and renders it more sober."[5]: 51

Augustine of Hippo, his North African contemporary, had in early life led a hedonistic lifestyle which changed dramatically following his conversion. In his Confessions, echoing Plato, he says about imitating others: "To the end that we may be true to our nature, we should not become false by copying and likening to the nature of another, as do the actors and the reflections in the mirror ... We should instead seek that truth which is not self-contradictory and two-faced."[5]: 57, 58 Augustine also challenged the cult of personality, maintaining that hero worship was a form of idolatry in which adulation of actors replaced the worship of God, leading people to miss their true happiness.

"For in the theatre, dens of iniquity though they may be, if a man is fond of a particular actor, and enjoys his art as a great or even as the very greatest good, he is fond of all who join with him in admiration of his favorite, not for their own sakes, but for the sake of him whom they admire in common; and the more fervent he is in his admiration, the more he works in every way he can to secure new admirers for him, and the more anxious he becomes to show him to others; and if he find anyone comparatively indifferent, he does all he can to excite his interest by urging his favorite's merits. If, however, he meet with anyone who opposes him, he is exceedingly displeased by such a man's contempt of his favorite, and strives in every way he can to remove it. Now, if this be so, what does it become us to do who live in the fellowship of the love of God, the enjoyment of whom is the true happiness of life...?"

Theatre and church in the Middle Ages

Around AD 470, as Rome declined, the Roman Church increased in power and influence, and theater was virtually eliminated.[6] In the Middle Ages, theatrical performance re-emerged as part of church life, telling Bible stories in a dramatic way; the aims of the church and of theater had now converged and there was very little opposition..

One of the few surviving examples of anti-theatrical attitude is found in A Treatise of Miraclis Pleyinge, a fourteenth-century sermon by an anonymous preacher. The sermon is generally agreed to be of Lollard inspiration. It is not clear if the text refers to the performance of mystery plays on the streets or to liturgical drama in the church. Possibly the author makes no distinction. Barish traces the basis of the preacher's prejudice to the lifelike immediacy of the theater, which sets it in unwelcome competition to everyday life and to the doctrines held in schools and churches. The preacher declares that since a play's basic objective is to please, its purpose must be suspect because Christ never laughed. If one laughs or cries at a play it is because of the "pathos of the story". One's expression of emotion is therefore useless in the eyes of God. The playmaking itself is at fault. "It is the concerted, organized, professionalized nature of the enterprise that offends so deeply, the fact that it entails planning and teamwork and elaborate preparation, making it different from the kind of sin that is committed inadvertently, or in a fit of ungovernable passion."[5]: 66–70

16th and 17th century English theatre

Theatricality in the church

In 1559, Thomas Becon, an English priest, wrote The Displaying of the Popish Mass, an early expression of emerging Protestant theology, while in exile during the reign of Queen Mary.[7] His argument was with the Church and the ritualised theatricality of the mass. "By introducing ceremonial costume, ritual gesture, and symbolic decor, and by separating the clergy from the laity, the church has perverted a simple communal event into a portentous masquerade, a magic show designed to hoodwink the ignorant." He believed that in a mass with too much pomp, the laity became passive spectators, entertained in a production that became a substitute for the message of God.[5]: 161, 165

English Renaissance theatre

The first English theatres were not built until the last quarter of the 16th century. One in eight Londoners regularly watched performances of Marlowe, Shakespeare, Jonson and others, an attendance rate only matched since by cinema around 1925–1939.[8] Objections were made, to live performances rather than to dramatic work itself or to its writers,[9] and some objectors made an explicit exception for closet dramas, especially those that were religious or had religious content.[10]

Variations of Plato's reasoning on mimesis re-emerged. One problem was the representation of rulers and the high-born by those of low birth.[11] Another issue was that of effeminization in the boy player when he took on female clothing and gesture. Both Ben Jonson and Shakespeare used cross-dressing as significant themes within their plays, and Laura Levine (1994) explores this issue in Men in Women's Clothing: Anti-theatricality and Effeminization, 1579-1642. In 1597 Stephen Gosson said that theatre "effeminized" the mind, and four years later Philip Stubbes claimed that male actors who wore women's clothing could "adulterate" male gender. Further tracts followed, and 50 years later William Prynne who described a man whom cross-dressing had caused to "degenerate" into a woman. Levine suggests these opinions reflect a deep anxiety over collapse into the feminine.[12]

Gosson and Stubbs were both playwrights. Ben Jonson was against the use of theatrical costume because it lent itself to unpleasing mannerisms and an artificial triviality.[5]: 151 In his plays, he rejected the Elizabethan theatricality that often relied on special effects, regarding it as involving false conventions.[5]: 134–135 His own court masques were expensive, exclusive spectacles.[13] He put typical anti-theatrical arguments into the mouth of his Puritan preacher Zeal-of-the-Land-Busy, in Bartholomew Fair, including the view that men mimicking women was forbidden in the Bible, in that the Book of Deuteronomy 22 verse 5, the text states that "The woman shall not wear that which pertaineth unto a man, neither shall a man put on a woman's garment: for all that do so are an abomination unto the Lord thy God." [KJV][14][15]

Puritan opposition

William Prynne's encyclopedic Histriomastix: The Player's Scourge, or Actor's Tragedy, represents the culmination of the Puritan attack on English Renaissance theatre and on celebrations such as Christmas, the latter alleged to have been derived from pagan Roman festivals. Although a particularly acute and comprehensive attack which emphasised spiritual and moral objections, it represented a common anti-theatrical view held by many during this time.

Prynne's outstanding objection to theater was that it encouraged pleasure and recreation over work, and that its excitement and effeminacy increased sexual desire.[5]: 83–85, 88

Published in 1633, the Histriomastix scourged many types of theater in broad, repetitious, and fiery ways. The title page reads:

"Histrio-mastix. The players scourge, or, actors tragædie, divided into two parts. Wherein it is largely evidenced, by divers arguments, by the concurring authorities and resolutions of sundry texts of Scripture, that popular stage-playes are sinfull, heathenish, lewde, ungodly spectacles, and most pernicious corruptions; condemned in all ages, as intolerable mischiefes to churches, to republickes, to the manners, mindes, and soules of men. And that the profession of play-poets, of stage-players; together with the penning, acting, and frequenting of stage-playes, are unlawfull, infamous and misbeseeming Christians. All pretences to the contrary are here likewise fully answered; and the unlawfulnes of acting, of beholding academicall enterludes, briefly discussed; besides sundry other particulars concerning dancing, dicing, health-drinking, &c. of which the table will informe you."

1642–1660 Theatre closure

By 1642, the Puritan view prevailed. As the First English Civil War got underway, London theaters were closed down. The order cited the current "times of humiliation" and their incompatibility with "public stage-plays", representative of "lascivious Mirth and Levity".[16] After the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, the performance of plays was again allowed. Under a new licensing system, two London theatres with royal patents were opened.[17]

Restoration theatre

Initially, the theatres performed many of the plays of the previous era, though often in adapted forms, but soon, new genres of Restoration comedy and Restoration spectacular evolved. A Royal Warrant from Charles II, who loved the theatre, brought English women onto the stage for the first time, putting an end to the practice of the 'boy player' and creating an opportunity for actresses to take on 'breeches' roles. This, says historian Antonia Fraser, meant that Nell Gwynn, Peg Hughes and others could show off their pretty legs in shows more titillating than ever before.[18]

Historian George Clark (1956) said the best-known fact about Restoration drama was that it was immoral. The dramatists mocked at all restraints. Some were gross, others delicately improper. "The dramatists did not merely say anything they liked: they also intended to glory in it and to shock those who did not like it."[19] Antonia Fraser (1984) took a more relaxed approach, describing the Restoration as a liberal or permissive era.[20]

The satirist, Tom Brown (1719) wrote, 'tis as hard a matter for a pretty Woman to keep herself honest in a Theatre as 'tis for an Apothecary to keep his treacle from the Flies in Hot Weather, for every Libertine in the Audience will be buzzing about her Honey-Pot...'[21]

The Restoration ushered in the first appearance of the casting couch in English social history. Most actresses were poorly paid and needed to supplement their income in other ways. Of the eighty women who appeared on the Restoration stage, twelve enjoyed an ongoing reputation as courtesans, being maintained by rich admirers of rank (including the King); at least another twelve left the stage to become 'kept women' or prostitutes. It was generally assumed that thirty of the women who had brief stage careers came from the brothels and had later returned to them. About a quarter of the actresses were considered to live respectable lives, most being married to fellow actors.[22]

Fraser reports that 'by the 1670s a respectable woman could not give her profession as "Actoress" and expect to keep either her reputation or her person intact... The word actress had secured in England that raffish connotation which would linger round it, for better or for worse, in fiction as well as in fact, for the next 250 years.'[23]

17th century Europe

Jansenism was the moral adversary to the theater in France, and in that respect similar to Puritanism in England. However, Barish argues, "the debate in France proceeds on an altogether more analytical, more intellectually responsible plane. The antagonists attend more carefully to the business of argument and the rules of logic; they indulge less in digression and anecdote."[5]: 193

Jansenism

Jansenists, rather like the Calvinists, denied the freedom of human will stating that "man can do nothing—could not so much as obey the ten commandments—without an express interposition of grace, and when grace came, its force was irresistible". Pleasure was forbidden because it became addictive.[5]: 200–201 According to Pierre Nicole, a distinguished Jansenist, the moral objection was, not so much about the makers of theater, or about the vice-den of the theater-space itself, or about the disorder it is presumed to cause, but rather about the intrinsically corrupting content. When an actor expresses base actions such as lust, hate, greed, vengeance, and despair, he must draw upon something immoral and unworthy in his own soul. Even positive emotions must be recognised as mere lies performed by hypocrites. The concern was a psychological one for, by experiencing these things, the actor stirs up heightened, temporal emotions, both in himself and in the audience, emotions that need to be denied. Therefore, both the actor and audience should feel ashamed for their collective participation.[5]: 194, 196

Francois de La Rochefoucauld (1731)

In 'Reflections on the Moral Maxims',[24] Francois de La Rochefoucauld wrote about the innate manners we were all born with and "when we copy others, we forsake what is authentic to us and sacrifice our own strong points for alien ones that may not suit us at all". By imitating others, including the good, all things are reduced to ideas and caricatures of themselves. Even with the intent of betterment, imitation leads directly to confusion. Mimesis ought therefore to be abandoned entirely.[5]: 217, 219–20

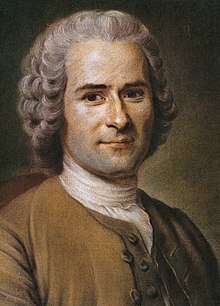

Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the Genevan philosopher, held the primary belief that all men were created good and that it was society that attempted to corrupt. Luxurious things were primarily to blame for these moral corruptions and, as stated in his Discourse on the Arts, Discourse on the Origins of Inequality and Letter to d'Alembert, the theater was central to this downfall. Rousseau argued for a nobler, simpler life free of the "perpetual charade of illusion, created by self-interest and self-love".The use of women in theater was disturbing for Rousseau; he believed women were designed by nature especially for modest roles and not for those of an actress. "The new society is not in fact to be encouraged to evolve its own morality but to revert to an earlier one, to the paradisal time when men were hardy and virtuous, women housebound and obedient, young girls chaste and innocent. In such a reversion, the theater—with all it symbolizes of the hatefulness of society, its hypocrisies, its rancid politeness, its heartless masqueradings—has no place at all."[5]: 257–258, 282, 294

18th century

By the end of the 17th century, the moral pendulum had swung back. Contributory factors included the Glorious Revolution of 1688, William and Mary's dislike of the theatre, and the lawsuits brought against playwrights by the Society for the Reformation of Manners (founded in 1692). When Jeremy Collier attacked playwrights like Congreve and Vanbrugh in his Short View of the Immorality and Profaneness of the English Stage in 1698, accusing them of profanity, blasphemy, indecency, and undermining public morality through the sympathetic depiction of vice, he was confirming a shift in audience taste that had already taken place.

Censorship

Censorship of stage plays had been exercised by the Master of the Revels in England from Elizabethan times until the order closing theatres in 1642, closure remaining until the Restoration in 1660. In 1737, a pivotal moment in theatrical history, Parliament enacted the Licensing Act, a law to censor plays on the basis of both politics and morals (sexual impropriety, blasphemy, and foul language). It also limited spoken drama to the two patent theatres. Plays had to be licensed by the Lord Chamberlain. Parts of these law were enforced unevenly. The act was modified by the Theatres Act 1843, which led later to the building of many new theatres across the country. Censorship was only finally abolished by the Theatres Act in 1968. (As the new medium of film developed in the 20th Century, the 1909 Cinematograph Act was passed. Initially a health and safety measure, its implementation soon included censorship. In time the British Board of Film Classification became the de facto film censor for films in the United Kingdom.)

Early America

In 1778, just two years after declaring the United States as a nation, a law was passed to abolish theater, gambling, horse racing, and cockfighting, all on the grounds of their sinful nature. This forced theatrical practice into the American universities where it is also met with hostility, particularly from Timothy Dwight IV of Yale University and John Witherspoon of Princeton College.[5]: 296 The latter, in his work, Serious Inquiry into the Nature and Effects of the Stage,[25] outlined similar arguments to his predecessors, but added a further moral argument that as theater was truthful to life, it was therefore an improper method of instruction. "Now are not the great majority of characters in real life bad? Must not the greatest part of those represented on the stage be bad? And therefore, must not the strong impression which they make upon the spectators be hurtful in the same proportion?"[5]: 297

William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce, a renowned English politician, had been a theatre-goer in his youth but, following an evangelical conversion while a Member of Parliament, gradually changed his attitudes, his behaviour and his lifestyle.[26] Most notably, he became a prime leader of the movement to stop the slave trade. The conspicuous involvement of Evangelicals and Methodists in the highly popular anti-slavery movement served to improve the status of a group otherwise associated with the less popular campaigns against vice and immorality.[27] Wilberforce expressed his views on authentic faith in A Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians, in the Middle and Higher Classes in this Country, Contrasted with Real Christianity (1797).[28] Barish summarises Wilberforce's description of contemporary theatre as 'a place haunted by debauchees bent on gratifying their appetites, from which modesty and regularity had retreated, while riots and lewdness were invited to the spot where God's name was profaned, and the only lessons to be learned were those Christians should shun like the pains of hell.'[5]: 303 The general tone of Wilberforce's argument is less contentious than Barish's summary would suggest and is only a small part of a wider call towards a true godliness. Wilberforce approaches theatricals tentatively, 'I am well aware that I am now about to tread on very tender ground; but it would be an improper deference to the opinions and manners of the age altogether to avoid it. There has been much argument concerning the lawfulness of theatrical amusements'.[28]: 202 Wilberforce also urged potential playgoers to consider the destructive impact of theatre on the moral and spiritual welfare of vulnerable actors.[28]: 209 Biographer and politician, William Hague, says of Wilberforce,[29]

His ambitious and energetic promotion of his views may well have contributed to the changed social conventions which dominated the Victorian age after his death, creating a British society very different from the licentious London against which he had revolted in the 1780s. As one of the ‘Fathers of the Victorians’ his views once again seem dated when seen from the vantage point of the more relaxed morality of later times, but in relation to his basic view that the long-term happiness of a society depends on how individuals behave towards each other, how families hold together, and how leaders keep the trust of people, who can say with confidence that he was wrong?

19th and early 20th century (psychomachia)

As theatre grew, so also did theatre-based anti-theatricality. Barish comments that from our present vantage point, nineteenth-century attacks on theater frequently have the air of a psychomachia, that is, a dramatic expression of the battle of good versus evil.[5]: 328–349

"The artistic conscience, struggling against the grossness of the physical stage, striving to free itself from the despotism of the actors, resembles the spirit warring against the flesh, the soul wrestling with the body, or the virtues launching their assault on the vices. But the persistence of the struggle seems to suggest that it is more than a temporary skirmish: it reflects an abiding tension in our natures as social beings."

Art versus theatre

Various notables including Lord Byron, Victor Hugo, Konstantin Stanislavsky, the actress Eleonora Duse, Giuseppe Verdi, and George Bernard Shaw, regarded the uncontrollable narcissism of Edmund Kean and those like him with despair. They were appalled by the self-regarding mania that the theatre induced in those whose lot it was to parade, night after night, before crowds of clamorous admirers. Playwrights found themselves driven towards closet drama, just to avoid the corruption of their work by self-aggrandizing actors.

For Romantic writers such as Charles Lamb, totally devoted to Shakespeare, stage performances inevitably sullied the beauty and integrity of the original work which the mind alone could appreciate. The fault of the theater lay in its superficiality. The delicacy of the written word was crushed by histrionic actors and distracting scenic effects.[5]: 326–9 In his essay On the Tragedies of Shakespeare, Considered with Reference to Their Fitness for Stage Representation, Lamb states that "all those delicacies which are so delightful in the reading...are sullied and turned from their very nature".[30]

Utopian philosopher Auguste Comte, although a keen theater-goer, like Plato, banned all theater from his idealist society. Theater was a "concession to our weakness, a symptom of our irrationality, a kind of placebo of the spirit with which the good society will be able to dispense".[5]: 323

The advent of Modernism would lead to a completely fresh and trenchant anti-theatricalism, beginning with attacks on Wagner who could be considered the 'inventor' of avant-garde theatricalism. Wagner became the object of Modernism's most polemic anti-theatrical attackers. Martin Puchner states that Wagner, 'almost like a stage diva himself, continues to stand for everything that may be grandiose and compelling, but also dangerous and objectionable, about the theatre and theatricality.' Critics have included Friedrich Nietzsche, Walter Benjamin and Michael Fried. Puchner argues that 'No longer interested in banishing actors or closing down theaters, modernist anti-theatricalism does not remain external to the theater but instead becomes a productive force responsible for the theater's most glorious achievements'.[4] Eileen Fisher (1982), describes the anti-theatrical as "spats, self criticism from theater practitioners and fine critics. Such 'prejudices' are usually based upon aesthetic dismay at our theaters' rampant commercialism, general triteness, boring star-system, narcissism, and overreliance on Broadway-style spectacle and razzmatazz."[31]

Church versus theatre

'Psychomachia' applies even more to.the battle of Church versus Stage. The Scottish Presbyterian Church's exertions concerning Kean were more overtly focussed on the spiritual battle. The English newspaper, The Era, sometimes known as the Actor's Bible, reported:[32]

"It is well-known that the Kirk of Scotland, strict, if not somewhat stern in its observances, is utterly opposed to all theatrical exhibitions; in fact, amusement of any kind is in direct opposition to the gloomy Calvinistic tenets on which the Presbyterian Kirk is based. Kean's arrival in Edinburgh made a great stir [c.1820]. In Auld Reekie, the more rigid viewed his coming with anything but pleasure. Many really pious and well-meaning teachers of the word were very strenuous in their exertions to prevent their flocks being contaminated by a visit under such strong temptations. A certain clergyman was extremely anxious to prevent any collision between the lambs of the elect and the children of Satan, as he conscientiously believed his followers and the Corps Dramatique to be, and earnestly cautioned the major part of his flock, particularly his own family, not to go near the theatre."

In 1860, the report of a sermon, a now occasional but still ferocious attack on the morality of the theatre, was submitted to The Era by an actor, S. Price:

"Sir, knowing your valuable paper to be the only medium through which the 'poor player' can defend himself and his honest calling against the bigotry, slander, and unchristian misrepresentations of certain reverend mawworms who occasionally attack the Drama and its expounders, I venture to forward you this communication... These aforesaid mawworms, creaming over with a superabundance of piety, and blinded by too much zeal, forget their divine calling, and stem to profit little by the divine behest which bears reference to evil-speaking and slander."

According to Price, who had attended the service, the minister declared that the present class of professionals, with very few exceptions, were dissipated in private and rakish in public, and that they pandered to the depraved and vitiated tastes of playgoers. Furthermore, theatre managers "held out the strongest inducements to women of an abandoned character to visit their theatres, in order to encourage the attendance of those of the opposite sex."[33]

In France the opposition was even more intense and ubiquitous. The Encyclopedie théologique (1847) records: "The excommunication pronounced against comedians, actors, actresses tragic or comic, is of the greatest and most respectable antiquity... it forms part of the general discipline of the French Church... This Church allows them neither the sacraments nor burial; it refuses them its suffrages and its prayers, not only as infamous persons and public sinners, but as excommunicated persons... One must deal with the comedians as with public sinners, remove them from participation with holy things while they belong to the theater, admit when they leave it."[5]: 321

Literature and theatricality

Walter Scott drew attention to vantage point when he recalled that a grand-aunt had asked him to get her some books by Restoration playwright Aphra Behn that she remembered from her youth. She later returned the books, recommending they be burnt and saying, "Is it not a very odd thing that I, an old woman of eighty and upwards, sitting alone, feel myself ashamed to read a book which, sixty years ago, I have heard read aloud for the amusement of large circles, consisting of the first and most creditable society in London."[34]

In Jane Austen's Mansfield Park (1814), Sir Thomas Bertram gives expression to social anti-theatrical views. Returning from his slave plantations in Antigua, he discovers his adult children preparing an amateur production of Elizabeth Inchbald's Lovers Vows. He argues vehemently, using statements such as "unsafe amusements" and "noisy pleasures" that will "offend his ideas of decorum" and burns all unbound copies of the play. Fanny Price, the heroine judges that the two leading female roles in Lovers Vows are "unfit to be expressed by any woman of modesty". Mansfield Park, with its strong moralist theme and criticism of corrupted standards, has generated more debate than any other of Austen's works, polarising supporters and critics. It sets up an opposition between a vulnerable young woman with strongly held religious and moral principles against a group of worldly, highly cultivated, well-to-do young people who pursue pleasure without principle.[35] Austen herself was an avid theatregoer and an admirer of actors like Kean. In childhood she had participated in full-length popular plays (and several written by herself) that were supervised by her clergyman father, performed in the family dining room and at a later stage in the family barn where theatrical scenery was stored.[36][37]

Barish suggests that by 1814 Austen may have turned against theatre following a supposed recent embracing of evangelicalism.[5]: 300–301 Claire Tomalin (1997) argues that there is no need to believe Austin condemned plays outside Mansfield Park and every reason for thinking otherwise.[35] Paula Byrne (2017) records that only two years before writing Mansfield Park, Austen, who was said to be a fine actor, had played the part of Mrs Candour in Sheridan’s popular contemporary play, The School for Scandal with great aplomb.[38] She continued to visit the theatre after writing Mansfield Park. Byrne also argues strongly that Austen's novels have considerable dramatic structure, making them particularly adaptable for screen representation.[36] A careful reading of Austen's text shows that while there is considerable debate about the propriety of amateur theatre, even Edmund and Fanny, who both oppose the production, have an appreciation of good theatricals.

In Thackeray's Vanity Fair (1847), Becky Sharp, exceptionally gifted with mimicry, is looked upon with much suspicion. Her talents of mimesis lend themselves to "a calculated deceptiveness" and "systematic concealment of her true intentions" that is unbecoming of any British woman.[5]: 307–310

Building bridges

Earlier divergence of church and stage

An editorial in The Era, quoted a contemporary writer outlining the history of the divergence of Church and Stage following the Middle Ages, and arguing that the conflict was unnecessary:

"So long as the drama had been content to be mainly the echo of the pulpit, some bond of sympathy, however slight, continued to exist between priests and players. But as soon as the theatre claimed to have a voice of its own, to have its own aims and objects, its own field of enterprise, its own mode of action, that bond was broken. The functions of the church were found to be different from those of the theatre; and because their functions were different the fatal fallacy, which has been, and still is, the cause of so much misunderstanding, sprang at once into existence, that therefore their interests must be opposed."

— 'Clerical Showmen', The Era, 13 November 1886

In the second half of the 19th century, Evangelical Christians established many societies for the relief of poverty. Some were created to help working women, particularly those whose occupation placed them in 'exceptional moral danger'. Evangelical groups tended towards 'charity' for the oppressed. 'Christian Socialists', distinctively different, (as in the Church and Stage Guild) were more likely to direct their energies towards what they considered to be the root causes of poverty.

1873 The Theatrical Mission

The Theatrical Mission was formed by two Evangelicals in 1873 to support vulnerable girls employed in travelling companies, the first being a group in a company that went on tour after performing their pantomime at the Crystal Palace. By 1884, the Mission was sending out some 1,000 supportive letters a month. They then opened a club, 'Macready House', in Henrietta Street, close to the London theatres, that provided cheap lunches and teas, and later, accommodation. They looked after children employed on the stage and, for any girl who was pregnant, encouraged her to seek help from the Theatre Ladies Guild which would arrange for the confinement and find other work for her after the baby was born.[39] The Mission attracted royal patronage. Towards the end of the century, an undercover journalist from The Era investigated Macready House, reporting it as 'patronising to the profession' and sub-standard.[40]

1879 Church and Stage Guild

In November 1879, The Era, responding to a resurgence of interest in religious circles about the Stage, reported a lecture defending the stage at a Nottingham church gathering. The speaker noted increased tolerance amongst church people and approved of the recent formation of the Church and Stage Guild. For too long, the clergy had referred to theatre as the 'Devil's House'. The chairman in his summary stated that while there was good in the theatre, he did not think the clergy could support the Stage as presently constituted.[41]

The Church and Stage Guild had been founded earlier that year by the Rev Stewart Headlam on 30 May. Within a year it had more than 470 members with at least 91 clergy and 172 professional theatre people. Its mission included breaking down "the prejudice against theatres, actors, music hall artists, stage singers, and dancers."[42] Headlam had been removed from his previous post by John Jackson, Bishop of London, following a lecture Headlam gave in 1877 entitled Theatres and Music Halls in which he promoted Christian involvement in these establishments. Jackson, writing to Headlam, and after distancing himself from any Puritanism, said, "I do pray earnestly that you may not have to meet before the Judgment Seat those whom your encouragement first led to places where they lost the blush of shame and took the first downward step towards vice and misery."[43]

1895 "The Sign of the Cross"

The Kansas City Journal reported on Wilson Barrett's new play, a religious drama, The Sign of the Cross, a work intended to bring church and stage closer together.[44]

Tonight at the Grand opera house Wilson Barrett produced his new play, "The Sign of the Cross." to a large audience. It is a professed attempt to conciliate the prejudices which church members are said to have for the stage and to bring the two nearer together. Of the play, the actor-author says: "With 'The Sign of the Cross' I stand today half way over the bridge that I have striven to construct to span the gulf between the two. I think it is but justice to expect the denouncers of my profession to come the other half of the way to meet me."

Ben Greet, an English actor-manager with a number of companies, formed a touring Sign of the Cross Company. The play proved particularly popular in England and Australia and was performed for several decades, often drawing audiences that did not normally attend the theatre.

1865–1935 A theatre manager's perspective

William Morton was a provincial theatre manager in England whose management experience spanned the 70 years between 1865 and 1935. He often commented on his experiences of theatre and cinema, and also reflected on national trends. He challenged the church when he believed it to be judgmental or hypocritical. He also strove to bring quality entertainment to the masses, though the masses did not always respond to his provision. Over his career, he reported a very gradual acceptance of theatre by the 'respectable classes' and by the church. Morton was a committed Christian though not a party man in religion or politics. A man of principle, he maintained an unusual policy of no-alcohol in all his theatres.

1860s bigotry

Morton commented in his memoirs, "At this period there was more bigotry than now. As a rule the religious community looked upon actors and press men as less godly than other people."[45] "Prejudice against the theatre was widespread amongst the respectable classes whose tastes were catered for by non-theatrical shows."[46] The Hull Daily Mail echoed, "To many of extreme religious views, his profession was anathema". It also reported that many had considered Morton's profession "a wasteful extravagance which lured young people from the narrow path they should tread".[47]

1910 The same goal

Morton stated in a public lecture held at Salem Chapel that he censured clergy "when they go out their way to preach against play-acting and warn their flock not to see it".[48] In another lecture he said that "the Protestant Church took too prejudiced a view against the stage. Considering their greater temptations I do not consider that actors are any worse than the rest of the community. Both the Church and the Stage are moving to the same goal. No drama is successful which makes vice triumphant. Many of the poor do not go to church and chapel, and but for the theatre they might come to fail to see the advantage in being moral".[49]

1921 Actor's Church Union

Morton received a circular from a Hull vicar, Rev. R. Chalmers. It described his small parish as full of evil-doing aliens, the crime-plotting homeless and a floating population of the theatrical profession. Said The Stage, this "represents a survival of that antagonistic spirit to the stage which the work of the Actors' Church Union has done so much to kill".[50] (Chalmers was noted for his charitable work so the real issue may have been more about poor communication.)

1938 Greater tolerance

Morton lived to see greater tolerance. On his hundredth birthday the Hull Daily Mail said Morton was held in great respect, "even by those who would not dream of entering any theatre. Whatever he brought for his patrons, grand opera, musical comedy, drama, or pantomime, came as a clean, wholesome entertainment."[47]

References

- ^ Pace, Eric (7 April 1998). "Jonas Barish, 76, Scholar of Theater History". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ^ Jean Kinney Williams (1 January 2009). Empire of Ancient Greece. Infobase Publishing. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-4381-0315-0.

- ^ Lewis, Pericles (2007). The Cambridge Introduction to Modernism. Cambridge University Press. p. 193. ISBN 9780521828093.

- ^ a b Martin Puchner (1 April 2003). Stage Fright: Modernism, Anti-Theatricality, and Drama. JHU Press. p. 9ff. ISBN 978-0-8018-7776-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Barish, Jonas (1981). The Antitheatrical Prejudice. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press. ISBN 0520052161.

- ^ Graham, Rob, Theatre, A Crash Course, East Sussex, 2003, p.20

- ^ Becon, Thomas (1559). The Early Works of Thomas Becon: Being the Treatises Published by Him in the Reign of King Henry VIII. University Press. p. xii.

- ^ Graham (2003) p. 32

- ^ Michael O'Connell (13 January 2000). The Idolatrous Eye: Iconoclasm and Theater in Early-Modern England. Oxford University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-19-534402-8.

- ^ Marta Straznicky (25 November 2004). Privacy, Playreading, and Women's Closet Drama, 1550-1700. Cambridge University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-521-84124-5.

- ^ Mark Thornton Burnett; Adrian Streete; Ramona Wray (31 October 2011). The Edinburgh Companion to Shakespeare and the Arts. Edinburgh University Press. p. 267. ISBN 978-0-7486-3524-5.

- ^ Laura Levine, Men in Women's Clothing: Anti-theatricality and Effeminization, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1994

- ^ Brocket, Oscar G. (2007). History of the Theatre: Foundation Edition. Boston, New York, San Francisco: Pearson Education. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-205-47360-1.

- ^ Jane Milling; Peter Thomson (23 November 2004). The Cambridge History of British Theatre. Cambridge University Press. p. 464. ISBN 978-0-521-65040-3.

- ^ Barish, Jonas (1966). "The Antitheatrical Prejudice". Critical Quarterly. 8 (4): 340. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8705.1966.tb01315.x.

- ^ Jane Milling; Peter Thomson (23 November 2004). The Cambridge History of British Theatre. Cambridge University Press. p. 439. ISBN 978-0-521-65040-3.

- ^ Brian Corman (21 January 2013). The Broadview Anthology of Restoration and Eighteenth-Century Comedy. Broadview Press. p. ix. ISBN 978-1-77048-299-9

- ^ Fraser, Antonia, Women's Lot in Seventeenth-Century England, vol. 2, London,1984, p.195

- ^ Clark, George (1956) The Later Stuarts, 1660-1714, Clarendon Press, Oxford. 2nd ed. p 369

- ^ Fraser, Antonia, Women's Lot in Seventeenth-Century England, vol. 1, 1984, pp. 365-6

- '^ Brown, Thomas, 'Letters from the Dead to the Living, 1719, cited in Fraser, 1984, vol 2, p. 198

- ^ Wilson, J.H. All the King's Ladies, Actresses of the Restoration, Chicago, 1958, pp. 109-192, quoted in Fraser, 1984 vol 2, p.197

- ^ Fraser, Antonia, Women's Lot in Seventeenth-Century England, Vol. 2, 1984, p.193

- ^ The Moral Maxims and Reflections of the Duke de La Rochefoucauld with an Introduction and Notes by George H. Powell (2 ed.). London: Methuen and Co. Ltd. 1912. Retrieved 7 January 2018

- ^ Witherspoon, John (1812). "Serious Inquiry into the Nature and Effects of the stage". Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ Hague, William. William Wilberforce: The Life of the Great Anti-Slave Trade Campaigner (2008) (Kindle Locations 1354-). HarperCollins Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Brown, Christopher Leslie (2006), Moral Capital: Foundations of British Abolitionism, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, pp. 386-387

- ^ a b c Wilberforce, William (1797). A Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians, in the Middle and Higher Classes in this Country, Contrasted with Real Christianity. Dublin: Kindle edition. pp. Section V.

- ^ Hague, Ch. 19 (Kindle Locations 9286-9291)

- ^ Lamb, Charles. "On the Tragedies of Shakspere Considered with Reference to Their Fitness for Stage Representation".

- ^ Fischer, Eileen (1982). "[Review of The Antitheatrical Prejudice by Jonas Barish]". Modern Drama. 25 (3). doi:10.1353/mdr.1982.0022.

- ^ Theatrical Recollections, The Era, 23 November 1856

- ^ 'The Theatre! Is the Stage Condusive to Morality?', The Era, 4 March 1860.

- ^ Lockhart, J. G. (1848). "Chapter 12 - The Life of Scott". www.arts.gla.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-02-07.

- ^ a b Tomalin, Claire. (1997). Jane Austen : a life (Penguin 1998 ed.). London: Viking. pp. 226–234. OCLC 41409993.

- ^ a b Byrne, Paula. The Real Jane Austen: A Life in Small Things, (2013) chapter 8 (Kindle Location 2471). HarperCollins Publishers.

- ^ Ross, Josephine. (2013) Jane Austen: A Companion (Kindle Location 1864-1869). Thistle Publishing. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Byrne, Paula (2017). The Genius of Jane Austen, Her Love of Theatre and Why She Is a Hit in Hollywood, (Kindle Locations 154). HarperCollins Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Heasman, Kathleen Evangelicals in Action London 1962 p. 277

- ^ Opinions are expressed in The Era, 10 February 1900, and on other dates.

- ^ Church and Stage, The Era, 23 November 1879 p.5

- ^ Joey A. Condon, An Examination Into the History and Present Interrelationship Between the Church and the Theatre Exemplified by the Manhattan Church of the Nazarene, the Lambs Club, and the Lamb's Theatre Company as a Possible Paradigm (ProQuest, 2007), p.148

- ^ Headlam, Stewart D, Theatres & music halls : a lecture given at the Commonwealth club, Bethnal Green, on Sunday, October 7, 1877. 2nd edition, London, Women's Printing Society, Ltd.

- ^ "The Kansas City Journal" (PDF). Chronicling America. 29 March 1895. p. 2. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ 'Early Days at Southport', Morton, William (1934). I Remember. (A Feat of Memory.). Market-place. Hull: Goddard. Walker and Brown. Ltd, pp. 40-44. (Morton had previously been a journalist.)

- ^ 'London's Entertainments in the Victorian Era', Morton, pp. 84-91

- ^ a b 'One Hundred And Fifty', Hull Daily Mail, 24 January 1938 p. 4

- ^ 'Mr. Morton on Amusement', The Era ,5 March 1910 p. 17

- ^ 'Secrets Of Success, "The Father Of Hull Theatres"', Hull Daily Mail, 15 November 1910, p. 7 {Lecture given by William Morton at the Fish Street Memorial Schoolroom}

- ^ 'Hull has a Hell—', The Stage, 17 March 1921 p.14

Further reading

- Davidson, C. (January 1997). "The Medieval Stage and the Antitheatrical Prejudice". Parergon. 14 (2): 1–14. doi:10.1353/pgn.1997.0019.

- Dennis, N. (March 2008). "The Illegitimate Theater. [Review of Against Theatre: Creative Destructions on the Modernist Stage]". Theatre Journal. 60 (1): 168–9. doi:10.1353/tj.2008.0058.

- Hawkes, D. (1999). "Idolatry and Commodity Fetishism in the Antitheatrical Controversy". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 39 (2): 255–73. doi:10.1353/sel.1999.0016.

- Stern, R. F. (1998). "Moving Parts and Speaking Parts: Situating Victorian Antitheatricality". ELH. 65 (2): 423–49. doi:10.1353/elh.1998.0016.

- Williams, K. (Fall 2001). "Anti-theatricality and the Limits of Naturalism". Modern Drama. 44 (3): 284–99. doi:10.3138/md.44.3.284.