Human Desire

| Human Desire | |

|---|---|

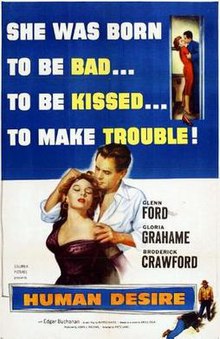

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Fritz Lang |

| Screenplay by | Alfred Hayes |

| Based on | the novel La Bête humaine 1890 novel by Émile Zola |

| Produced by | Lewis J. Rachmil |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Burnett Guffey |

| Edited by | Aaron Stell |

| Music by | Daniele Amfitheatrof |

Production company | Columbia Pictures |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 91 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Human Desire is a 1954 black-and-white film noir directed by Fritz Lang and starring Glenn Ford, Gloria Grahame and Broderick Crawford. It is loosely based on Émile Zola's 1890 novel La Bête humaine. The story had been filmed twice before: La Bête humaine (1938) directed by Jean Renoir and Die Bestie im Menschen starring Ilka Grüning (1920).

Plot

Returning Korean War vet Jeff Warren (Glenn Ford) is a train engineer who worked alongside Alec Simmons (Edgar Buchanan), and was a boarder in his home, before going off to fight for three years. Jeff has moved back in and is resuming his duties as an engineer. Alec's daughter, Ellen (Kathleen Case), always had a crush on Jeff and, in the interim, has matured into a very attractive young woman who's obviously still smitten with him.

Carl Buckley (Broderick Crawford) is a gruff, hard-drinking assistant yard supervisor married to the younger, and more vibrant, Vicki (Gloria Grahame). When Carl is fired for talking back to his boss, he pleads with Vicki to go into the city to see John Owens (Grandon Rhodes), in whose house she lived as a young girl when her mother worked for Owens as a housekeeper. He is an important customer of the railroad, whose influence Carl hopes will result in him getting his job back.

Unbeknownst to Carl, Vicki had more than just lived in Owens' house, which the viewer can surmise from Vicki's almost firm but subdued refusal to intercede on her husband's behalf. Nonetheless, after his persistent begging, she reluctantly agrees to go into the city to meet Owens and ask for his help. From her manner, and the way in which Owens greets her, we can tell what Vicki will do in order to get Carl rehired.

When Vicki doesn't return for almost five hours, it dawns on Carl that she's been unfaithful. After a violent argument during which he slaps the truth from her, Carl forces Vicki to write a short letter to Owens, setting up a meeting with him later that night in his train compartment. He's taking the train to Chicago and Carl and Vicki are returning home. Carl accompanies Vicki to Owens' compartment, barges in when Owens opens the door, and, with the knife he'd been whittling with on his way into town earlier in the day, Carl kills him. He then takes Owens' wallet and his pocket watch to make the murder appear to be one done in the course of a robbery, and he also takes the letter that Vicki had written. Carl makes it clear that he's keeping the letter as insurance against Vicki's going to the police.

Meanwhile, Jeff, who had driven the train Carl and Vicki had taken into town, is now hitching a free ride back home and happens to be smoking in the vestibule near Owens' compartment, blocking the couple's way back to their own. Carl makes Vicki entice Jeff, who isn't acquainted with her, away from the area so Carl can make his way unseen. Vicki and Jeff share a smoke, and a kiss. At the end of the journey, Jeff sees Carl and Vicki together and realizes they're married.

At the inquest for the murder of Owens, Jeff is called as a witness. The various passengers on the train that night are asked to stand. When he's asked if he had seen any of the people that night, Jeff looks intently at Vicki, then answers no.

Vicki and Jeff soon resume their relationship; she tells him how she's come to be married to Carl and shows him marks on her where Carl has beaten her. She reveals a truncated version of the truth, that she'd gone to Owens' compartment for a liaison, but had found him murdered. Jeff questions how she'd shown no sign of distress when she'd come upon him in the vestibule. Vicki explains that she's frightened of Carl's temper.

Meanwhile, Ellen still harbors her feelings for Jeff and sells him a ticket to a local dance; she clearly hopes he'll ask her to go with him, but she also reveals that she knows he's involved with Vicki.

Jeff tells Vicki he wants to marry her, that she should leave her husband. She finally tells the entire truth about Owens' murder and about the letter. Captivated even still, Jeff says they will work it all out somehow.

Carl has become a drunk and has again lost his job. Vicki summons Jeff to let him know that her husband is selling the house and is making her leave town with him. She can't find the letter anywhere, so suspects Carl must keep it with him. She suggests that she and Jeff will have to part forever and says, "If only we'd been luckier. If something had happened to him, at the yards." Jeff understands her implication.

Carl stumbles, drunk, from Duggan's Bar and starts making his way home through the rail yard. Jeff follows, clutching a large monkey wrench he's retrieved from a tool locker there. A passing train blocks the view, but the viewer will assume Jeff has bludgeoned Carl to death. However, Jeff appears at Vicki's, saying he couldn't do it. He accuses Vicki of setting him up from the start just so he would kill her husband. She protests that she really does love Jeff and that if he loved her he would've killed for her. She tries to equate his Korean War experience in killing men with this situation. Jeff leaves her, but gives her one thing as he goes –– the letter, which he has taken from the drunk Carl's pocket.

Vicki is now free to leave Carl and, alone, gets on the next train, which Jeff is engineering. Shortly after it leaves the station, Carl enters Vicki's compartment. He implores her not to leave him, even offers her the letter, but, as he's searching for it in his pockets, she tells him he doesn't have it. He then accuses her of running away with Jeff. She denies this but admits she's in love with Jeff, though he's rejected her because she asked him to murder Carl. Carl strangles her to death.

Meanwhile, Jeff has regained some happiness and, as he operates the train, is thinking about the dance he and Ellen will attend together.

Cast

- Glenn Ford as Jeff Warren

- Gloria Grahame as Vicki Buckley

- Broderick Crawford as Carl Buckley

- Edgar Buchanan as Alec Simmons

- Kathleen Case as Ellen Simmons

- Peggy Maley as Jean

- Diane DeLaire as Vera Simmons

- Grandon Rhodes as John Owens

Production

This film was largely shot in the vicinity of El Reno, Oklahoma.[1] It used the facilities of what was at the time the Rock Island Railroad (now Union Pacific),[2] though some of the moving background shots show East Coast scenes such as bridges including the Pulaski Skyway and the famous "Trenton Makes — The World Takes" bridge over the Delaware River.

Reception

Critic Dave Kehr wrote of the film, "Gloria Grahame, at her brassiest, pleads with Glenn Ford to do away with her slob of a husband, Broderick Crawford.... A gripping melodrama, marred only by Ford's inability to register an appropriate sense of doom."[3] Variety wrote that Lang "goes overboard in his effort to create mood."[4] Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote, "[T]here isn't a single character in it for whom it builds up the slightest sympathy—and there isn't a great deal else in it for which you're likely to have the least regard."[5]

Preservation

The Academy Film Archive preserved Human Desire in 1997.[6]

References

- ^ Medley, Robert (June 26, 1989). "USAO to Preserve State History at Film Repository". The Oklahoman. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ Carr, Jay (September 1, 2006). "Glenn Ford; actor's demeanor, quiet decency reflected an era". Boston.com. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ Kehr, Dave. Chicago Reader, review, 2008. Last accessed: January 27, 2007.

- ^ "Review: 'Human Desire'". Variety. 1954. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (August 7, 1954). "Human Desire (1954)". The New York Times. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ "Preserved Projects". Academy Film Archive.

External links

- 1954 films

- 1950s crime drama films

- American films

- American crime drama films

- English-language films

- American black-and-white films

- Adultery in films

- Film noir

- Rail transport films

- Columbia Pictures films

- Films based on French novels

- Films based on works by Émile Zola

- Films directed by Fritz Lang

- Films shot in Oklahoma

- Films scored by Daniele Amfitheatrof

- 1954 drama films