Sclaveni

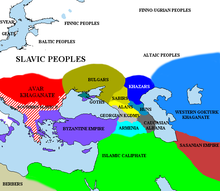

The Sclaveni (in Latin) or Sklavenoi (in Greek) were early Slavic tribes that raided, invaded and settled the Balkans in the Early Middle Ages and eventually became known as the ethnogenesis of the South Slavs. They were mentioned by early Byzantine chroniclers as barbarians having appeared at the Byzantine borders along with the Antes (East Slavs), another Slavic group. The Sclaveni were differentiated from the Antes and Wends (West Slavs); however, they were described as kin. Eventually, most South Slavic tribes accepted Byzantine suzerainty, and came under Byzantine cultural influence. The term was widely used as general catch-all term until the emergence of separate tribal names by the 10th century.

Terminology

The Byzantines broadly grouped the numerous Slav tribes living in proximity with the Eastern Roman Empire into two groups: the Sklavenoi and the Antes.[1] The Sclaveni were called as such by Procopius, and as Sclavi by Jordanes and Pseudo-Maurice (Greek: Σκλαβηνοί (Sklabēnoi), Σκλαυηνοί (Sklauēnoi), or Σκλάβινοι (Sklabinoi); Latin: Sclaueni, Sclavi, Sclauini, or Sthlaueni - Sklaveni). The derived Greek term Sklavinia(i) (Σκλαβινίαι; Template:Lang-lat) was used for Slav tribes in Byzantine Macedonia and the Peloponnese; these Slavic territories were initially outside of Byzantine control.[2] By 800, however, the term also referred specifically to Slavic mobile military colonists who settled as allies within the territories of the Byzantine Empire. Slavic military settlements appeared in the Peloponnese, Asia Minor, and Italy.

Byzantine historiography

Procopius gives the most detail about the Sclaveni and Antes.[3] The Sclaveni are also mentioned by Jordanes (fl. 551), Pseudo-Caesarius (560), Menander Protector (mid-6th c.), Strategikon (late 6th c.), etc.

History

6th century

The first Slavic raid south of the Danube was recorded by Procopius, who mentions an attack of the Antes, "who dwell close to the Sclaveni", probably in 518.[4][5] Scholar Michel Kazanski identified the 6th-century Prague culture and Sukow-Dziedzice group as Sclaveni archaeological cultures, and the Penkovka culture was identified as Antes.[3] In the 530s, Emperor Justinian seems to have used divide and conquer and the Sclaveni and Antes are mentioned as fighting each other.[6]

Sclaveni are first mentioned in the context of the military policy on the Danube frontier of Byzantine Emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565).[7] In 537, 1,600 cavalry, made up of mostly Sclaveni and Antes, were shipped by Justinian to Italy to rescue Belisarius.[8] Sometime between 533–34 and 545 (probably before the 539–40 Hun invasion),[8] there was a conflict between the Antes and Sclaveni in Eastern Europe.[9] Procopius noted that the two "became hostile to one another and engaged in battle" until a Sclaveni victory.[8] The conflict was likely aided or initiated by the Byzantines.[9] In the same period, the Antes raided Thrace.[10] The Romans also recruited mounted mercenaries from both tribes against the Ostrogoths.[8] The two tribes were at peace by 545.[10] Notably, one of the captured Antes claimed to be Roman general Chilbudius (who was killed in 534 by barbarians at the Danube). He was sold to the Antes and freed. He revealed his true identity but was pressured and continued to claim that he was Chilbudius.[10] The Antes are last mentioned as anti-Byzantine belligerents in 545, and the Sclaveni continued to raid the Balkans.[9] The Antes became Roman allies by treaty in 545.[11] Between 545 and 549, the Sclaveni raided deep into Roman territory.[12] In 547, 300 Antes fought the Ostrogoths in Lucania.[11] In the summer of 550, the Sclaveni came close to Naissus, and were seen as a great threat, however, their intent on capturing Thessaloniki and the surroundings was thwarted by Germanus.[13] After this, for a year, the Sclaveni spent their time in Dalmatia "as if in their own land".[13] The Sclaveni then raided Illyricum and returned home with booty.[14] In 558 the Avars arrived at the Black Sea steppe, and defeated the Antes between the Dnieper and Dniester.[15] The Avars subsequently allied themselves with the Sclaveni.[16]

Daurentius (fl. 577–579), the first Slavic chieftain recorded by name, was sent an Avar embassy requesting his Slavs to accept Avar suzerainty and pay tribute, because the Avars knew that the Slavs had amassed great wealth after repeatedly plundering the Balkans. Daurentius reportedly retorted that "Others do not conquer our land, we conquer theirs [...] so it shall always be for us", and had the envoys slain.[17] Bayan then campaigned (in 578) against Daurentius' people, with aid from the Byzantines, and set fire to many of their settlements, although this did not stop the Slavic raids deep into the Byzantine Empire.[18] In 578, a large army of Sclaveni devastated Thrace and other areas.[19] In the 580s, the Antes were bribed to attack Sclaveni settlements.[11]

John of Ephesus noted in 581: "the accursed people of the Slavs set out and plundered all of Greece, the regions surrounding Thessalonica, and Thrace, taking many towns and castles, laying waste, burning, pillaging, and seizing the whole country." However, John exaggerated the intensity of the Slavic incursions since he was influenced by his confinement in Constantinople from 571 up until 579.[20] Moreover, he perceived the Slavs as God's instrument for punishing the persecutors of the Monophysites.[20] By the 580s, as the Slav communities on the Danube became larger and more organised, and as the Avars exerted their influence, raids became larger and resulted in permanent settlement. By 586, they managed to raid the western Peloponnese, Attica, Epirus, leaving only the east part of Peloponnese, which was mountainous and inaccessible. In 586 AD, as many as 100,000 Slav warriors raided Thessaloniki. The final attempt to restore the northern border was from 591 to 605, when the end of conflicts with Persia allowed Emperor Maurice to transfer units to the north. However he was deposed after a military revolt in 602, and the Danubian frontier collapsed one and a half decades later (see Maurice's Balkan campaigns).

7th century

In 602, the Avars attacked the Antes; this is the last mention of Antes in historical sources.[21] In 615, during the reign of Heraclius (r. 610–641), the whole Balkans was regarded as Sklavinia – inhabited or controlled by Slavs.[22] Chatzon led the Slavic attack on Thessaloniki that year.[23] The Slavs asked the Avars for aid, resulting in an unsuccessful siege (617).[23] In 626, Sassanids, Avars and Slavs joined forces and unsuccessfully besieged Constantinople.[24] During the same year of the siege, the Sclaveni used their monoxyla in order to transport the 3,000 troops of the allied Sassanids across the Bosphorus which the latter had promised the khagan of the Avars.[25] In 630, Sclaveni attempted to take Thessaloniki again.[citation needed] Traditional historiography, based on DAI, holds that the migration of Croats and Serbs to the Balkans was part of a second Slavic wave, placed during Heraclius' reign.[26]

Constans II conquered Sklavinia in 657–658, "capturing many and subduing",[27] and settled captured Slavs in Asia Minor; in 664–65, 5,000 of these joined Abdulreman ibn Khalid.[28] Perbundos, the chieftain of the Rhynchinoi, a powerful tribe near Thessaloniki, planned a siege on Thessaloniki but was imprisoned and eventually executed after escaping prison; the Rhynchinoi, Strymonitai and Sagoudatai made common cause, rose up and laid siege to Thessaloniki for two years (676–678).[29]

Justinian II (r. 685–695) settled as many as 30,000 Slavs from Thrace in Asia Minor, in an attempt to boost military strength. Most of them however, with their leader Neboulos, deserted to the Arabs at the Battle of Sebastopolis in 692.[30]

8th century

Military campaigns in northern Greece in 758 under Constantine V (r. 741–775) prompted a relocation of Slavs under Bulgar aggression; again in 783.[31] The Bulgars had by 773 cut off the communication route, the Vardar valley, between Serbia and the Byzantines.[32] The Bulgars were defeated in 774, after Emperor Constantine V (r. 741–775) learnt of their planned raid.[33] In 783, a large Slavic uprising took place in the Byzantine Empire, stretching from Macedonia to the Peloponnese, which was subsequently quelled by Byzantine patrikios Staurakios (fl. 781–800).[34] Dalmatia, inhabited by Slavs in the interior, at this time, had firm relations with Byzantium.[35] In 799, Akameros, a Slavic archon, participated in the conspiracy against Empress Irene of Athens.[36]

Relationship between the Slavs in Byzantium

Byzantine literary accounts (i.e., John of Ephesus, etc.) mention the Slavs raiding areas of Greece during the 580s. According to later sources such as The Miracles of Saint Demetrius, the Drougoubitai, Sagoudatai, Belegezitai, Baiounetai, and Berzetai laid siege to Thessaloniki in 614–616.[37] However, this particular event was actually of local significance.[38] A combined effort of the Avars and Slavs two years later also failed to take the city. In 626, a combined Avar, Bulgar and Slav army besieged Constantinople. The siege was broken, which had repercussions upon the power and prestige of the Avar khanate. Slavic pressure on Thessaloniki ebbed after 617/618, until the Siege of Thessalonica (676–678) by a coalition of Rynchinoi, Sagoudatai, Drougoubitai and Stroumanoi attacked. This time, the Belegezites also known as the Velegeziti did not participate and in fact supplied the besieged citizens of Thessaloniki with grain. It seems that the Slavs settled on places of earlier settlements and probably merged later with the local populations of Greek descent to form a mixed Byzantine-Slavic communities. The process was stimulated by the conversion of the Slavic tribes to Orthodox Christianity on the Balkans, during the same period.[39]

A number of medieval sources attest to the presence of Slavs in Greece. While en route to the Holy Land in 732, Willibald "reached the city of Monemvasia, in the land of Slavinia". This particular passage from the Vita Willibaldi is interpreted as an indication of a Slavic presence in the hinterland of the Peloponnese.[41] In reference to the plague of 744–747, Constantine VII wrote during the 10th century that "the entire country [of the Peloponnese] was Slavonized".[42][better source needed] Another source for the period, the Chronicle of Monemvasia speaks of Slavs overrunning the western Peloponnese, but of the eastern Peloponnese, together with Athens, remaining in Byzantine hands throughout this period.[43] However, such sources are far from ideal,[44] and their reliability is debated. For example, while the Byzantinist Peter Charanis believes the Chronicle of Monemvasia to be a reliable account, other scholars point out that it greatly overstates the impact of the Slavic and Avar raids of Greece during this time.[45]

Max Vasmer, a prominent linguist and Indo-Europeanist, complements late medieval historical accounts by listing 429 Slavic toponyms from the Peloponnese alone.[41][46] To what extent the presence of these toponyms reflects compact Slavic settlement is a matter of some debate,[47] and might represent an accumulative strata of toponyms rather than being attributed to the earliest settlement phase.

Relations between the Slavs and Greeks were probably peaceful apart from the (supposed) initial settlement and intermittent uprisings.[48] Being agriculturalists, the Slavs probably traded with the Greeks inside towns.[43] Furthermore, the Slavs surely did not occupy the whole interior or eliminate the Greek population; some Greek villages continued to exist in the interior, probably governing themselves, possibly paying tribute to the Slavs.[43] Some villages were probably mixed, and quite possibly some degree of Hellenization of the Slavs by the Greeks of the Peloponnese had already begun during this period, before re-Hellenization was completed by the Byzantine emperors.[49]

When the Byzantines were not fighting in their eastern territories, they were able to slowly regain imperial control. This was achieved through its theme system, referring to an administrative province on which an army corps was centered, under the control of a strategos ("general").[50] The theme system first appeared in the early 7th century, during the reign of the Emperor Heraclius, and as the Byzantine Empire recovered, it was imposed on all areas that came under Byzantine control.[50] The first Balkan theme created was that in Thrace, in 680 AD.[50] By 695, a second theme, that of "Hellas" (or "Helladikoi"), was established, probably in eastern central Greece.[50] Subduing the Slavs in these themes was simply a matter of accommodating the needs of the Slavic elites and providing them with incentives for their inclusion into the imperial administration.

It was not until 100 years later that a third theme would be established. In 782–784, the eunuch general Staurakios campaigned from Thessaloniki, south to Thessaly and into the Peloponnese.[34] He captured many Slavs and transferred them elsewhere, mostly Anatolia (these Slavs were dubbed Slavesians).[51] However it is not known whether any territory was restored to imperial authority as result of this campaign, though it is likely some was.[34] Sometime between 790 and 802, the theme of Macedonia was created, centered on Adrianople (i.e., east of the modern geographic entity).[34] A serious and successful recovery began under Nicephorus I (802–811).[34] In 805, the theme of the Peloponnese was created.[52] According to the Chronicle of Monemvasia in 805 the Byzantine governor of Corinth went to war with the Slavs, obliterated them, and allowed the original inhabitants to claim their own;[52] the city of Patras was recovered and the region re-settled with Greeks.[53] In the 9th century, new themes continued to arise, although many were small and were carved out of original, larger themes. New themes in the 9th century included those of Thessalonica, Dyrrhachium, Strymon, and Nicopolis.[54] From these themes, Byzantine laws and culture flowed into the interior.[54] By the end of the 9th century most of Greece was culturally and administratively Greek again, with the exception of a few small Slavic tribes in the mountains such as the Melingoi and Ezeritai.[55] Although they were to remain relatively autonomous until Ottoman times, such tribes were the exception rather than the rule.[54]

Apart from military expeditions against Slavs, the re-Hellenization process begun under Nicephorus I involved (often forcible) transfer of peoples.[56] Many Slavs were moved to other parts of the empire, such as Anatolia and made to serve in the military.[57] In return, many Greeks from Sicily and Asia Minor were brought to the interior of Greece, to increase the number of defenders at the Emperor's disposal and dilute the concentration of Slavs.[53] Even non-Greeks were transferred to the Balkans, such as Armenians.[51] As more of the peripheral territories of the Byzantine Empire were lost in the following centuries, e.g., Sicily, southern Italy and Asia Minor, their Greek-speakers made their own way back to Greece. That the re-Hellenization of Greece through population transfers and cultural activities of the Church was successful suggests Slavs found themselves in the midst of many Greeks.[58] It is doubtful that such large number could have been transplanted into Greece in the 9th century; thus there surely had been many Greeks remaining in Greece and continuing to speak Greek throughout the period of Slavic occupation.[58] The success of re-Hellenization also suggests the number of Slavs in Greece was far smaller than the numbers found in the former Yugoslavia and Bulgaria.[58] For example, Bulgaria could not be Hellenized when Byzantine administration was established over the Bulgarians in 1018 to last for well over a century, until 1186.[58]

Eventually, the Byzantines recovered the imperial border north all the way to today's region of Macedonia (which would serve as the northern border of the Byzantine Empire until 1018), although independent Slavic villages remained. As the Slavs supposedly occupied the entire Balkan interior, Constantinople was effectively cut off from the Dalmatian cities under its (nominal) control.[59] Thus Dalmatia came to have closer ties with the Italian Peninsula, because of ability to maintain contact by sea (however, this too, was troubled by Slavic pirates).[59] Additionally, Constantinople was cut off from Rome, which contributed to the growing cultural and political separation between the two centers of European Christendom.[59]

See also

References

- ^ Hupchick 2004.

- ^ Andrew Louth (2007). Greek East and Latin West: The Church, AD 681-1071. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. pp. 171–. ISBN 978-0-88141-320-5.

- ^ a b James 2014, p. 96.

- ^ James 2014, p. 95.

- ^ Curta 2001, p. 75.

- ^ James 2014, p. 97.

- ^ Curta 2001, p. 76.

- ^ a b c d Curta 2001, p. 78.

- ^ a b c Byzantinoslavica. Vol. 61–62. Academia. 2003. pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b c Curta 2001, p. 79.

- ^ a b c Curta 2001, p. 81.

- ^ Curta 2001, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b Curta 2001, p. 86.

- ^ Curta 2001, p. 87.

- ^ Kobyliński 1995, p. 536.

- ^ Kobyliński 1995, p. 537–539.

- ^ Curta 2001, pp. 47, 91.

- ^ Curta 2001, pp. 91–92, 315

- ^ Curta 2001, p. 91.

- ^ a b Curta 2001, p. 48.

- ^ Kobyliński 1995, p. 539.

- ^ Jenkins 1987, p. 45.

- ^ a b Fine 1991, p. 41–44.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, pp. 297–299.

- ^ Howard-Johnston 2006, p. 33.

- ^ Curta 2001, p. 66.

- ^ Stratos 1975, p. 165.

- ^ Stratos 1975, p. 234.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Treadgold 1998, p. 26.

- ^ Vlasto 1970, p. 9.

- ^ Živković 2002, p. 230.

- ^ Fine 1991, pp. –77.

- ^ a b c d e Fine 1991, p. 79.

- ^ Živković 2002, p. 218.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 110.

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 41.

- ^ Curta 2001, p. 108.

- ^ Bintliff J.L. (2003), The ethnoarchaeology of a 'passive' ethnicity: The Arvanites of Central Greece, p. 142. In: Brown K.S., Hamilakis Y. (Eds.) The Usable Past. Greek Metahistories. Lanham-Boulder: Lexington Books. 129-144.

- ^ "Companion website for "A genetic atlas of human admixture history", Hellenthal et al, Science (2014)". A genetic atlas of human admixture history.

Hellenthal, Garrett; Busby, George B.J.; Band, Gavin; Wilson, James F.; Capelli, Cristian; Falush, Daniel; Myers, Simon (14 February 2014). "A Genetic Atlas of Human Admixture History". Science. 343 (6172): 747–751. Bibcode:2014Sci...343..747H. doi:10.1126/science.1243518. ISSN 0036-8075. PMC 4209567. PMID 24531965.

Hellenthal, G.; Busby, G. B.; Band, G.; Wilson, J. F.; Capelli, C.; Falush, D.; Myers, S. (2014). "Supplementary Material for "A genetic atlas of human admixture history"". Science. 343 (6172): 747–751. doi:10.1126/science.1243518. PMC 4209567. PMID 24531965.S7.6 "East Europe": The difference between the 'East Europe I' and 'East Europe II' analyses is that the latter analysis included the Polish as a potential donor population. The Polish were included in this analysis to reflect a Slavic language speaking source group." "We speculate that the second event seen in our six Eastern Europe populations between northern European and southern European ancestral sources may correspond to the expansion of Slavic language speaking groups (commonly referred to as the Slavic expansion) across this region at a similar time, perhaps related to displacement caused by the Eurasian steppe invaders (38; 58). Under this scenario, the northerly source in the second event might represent DNA from Slavic-speaking migrants (sampled Slavic-speaking groups are excluded from being donors in the EastEurope I analysis). To test consistency with this, we repainted these populations adding the Polish as a single Slavic-speaking donor group ("East Europe II" analysis; see Note S7.6) and, in doing so, they largely replaced the original North European component (Figure S21), although we note that two nearby populations, Belarus and Lithuania, are equally often inferred as sources in our original analysis (Table S12). Outside these six populations, an admixture event at the same time (910CE, 95% CI:720-1140CE) is seen in the southerly neighboring Greeks, between sources represented by multiple neighboring Mediterranean peoples (63%) and the Polish (37%), suggesting a strong and early impact of the Slavic expansions in Greece, a subject of recent debate (37). These shared signals we find across East European groups could explain a recent observation of an excess of IBD sharing among similar groups, including Greece, that was dated to a wide range between 1,000 and 2,000 years ago (37)

- ^ a b Fine 1991, p. 62.

- ^ Davis, Jack L. and Alcock, Susan E. Sandy Pylos: An Archaeological History from Nestor to Navarino. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1998, p. 215.

- ^ a b c Fine 1991, p. 61.

- ^ Fine 1983, p. 62

- ^ Mee, Christopher; Patrick, Michael Atherton; Forbes, Hamish Alexander (1997). A Rough and Rocky Place: The Landscape and Settlement History of the Methana Peninsula, Greece: Results of the Methana Survey Project, sponsored by the British School at Athens and the University of Liverpool. Liverpool, United Kingdom: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 9780853237419.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Max Vasmer (1941). "Die Slaven in Griechenland". Berlin: Verlag der Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- ^ Vacalopoulos, Apostolos E. (translated by Ian Moles). Origins of the Greek Nation: The Byzantine Period, 1204–1461. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1970, p. 6.

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 63.

- ^ Hupchick 2004, p. ?.

- ^ a b c d Fine 1991, p. 70.

- ^ a b Curta 2006, p. ?.

- ^ a b Fine 1991, p. 80.

- ^ a b Fine 1991, p. 82.

- ^ a b c Fine 1991, p. 83.

- ^ Fine 1991, pp. 79–83.

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 81.

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d Fine 1991, p. 64.

- ^ a b c Fine 1991, p. 65.

Sources

- Curta, Florin (2001). The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500–700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139428880.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521815390.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Michigan: The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Howard-Johnston, J. D. (2006). East Rome, Sasanian Persia and the End of Antiquity: Historiographical and Historical Studies. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0860789925.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hupchick, Dennis P. (2004). The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-6417-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kaimakamova, Miliana; Salamon, Maciej (2007). Byzantium, new peoples, new powers: the Byzantino-Slav contact zone, from the ninth to the fifteenth century. Towarzystwo Wydawnicze "Historia Iagellonica". ISBN 978-83-88737-83-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kobyliński, Zbigniew (1995). The Slavs. Cambridge University Press. pp. 524–. ISBN 978-0-521-36291-7.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - James, Edward (2014). Europe's Barbarians AD 200-600. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-86825-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Janković, Đorđe (2004). "The Slavs in the 6th Century North Illyricum". Гласник Српског археолошког друштва. 20: 39–61.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jenkins, Romilly James Heald (1987). Byzantium: The Imperial Centuries, AD 610-1071. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-6667-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Louth, Andrew (2007). Greek East and Latin West: The Church AD 681–1071. Crestwood, N.Y.: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press. ISBN 9780881413205.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stratos, Andreas Nikolaou (1968). Byzantium in the Seventh Century. Vol. 1. Adolf M. Hakkert.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stratos, Andreas Nikolaou (1968). Byzantium in the Seventh Century. Vol. 2. Adolf M. Hakkert. ISBN 978-0-902565-78-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stratos, Andreas Nikolaou (1975). Byzantium in the Seventh Century. Vol. 3. Adolf M. Hakkert.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Treadgold, Warren (1998). Byzantium and Its Army, 284-1081. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3163-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Treadgold, Warren T. (1997). A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804726306.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vlasto, A. P. (1970). The Entry of the Slavs into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval History of the Slavs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521074599.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Živković, Tibor (2008). Forging unity: The South Slavs between East and West 550-1150. Belgrade: Čigoja štampa.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Živković, Tibor (2002). Јужни Словени под византијском влашћу 600-1025 [South Slavs under the Byzantine Rule (600–1025)]. Belgrade: Историјски институт САНУ.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Đekić, Đorđe (2014). "Were the Sclavinias states?". Zbornik Matice Srpske Za Drustvene Nauke (in Serbian) (149): 941–947. doi:10.2298/ZMSDN1449941D.

External links

- "Byzantine Sources for History of the Peoples of Yugoslavia". Zbornik Radova. Vizantološki institut SANU: 19–51. 1955. (Public Domain)