Linamarin

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

2-methyl-2-[(2S,3R,4S,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-

| |

| Other names

Phaseolunatin

| |

| Identifiers | |

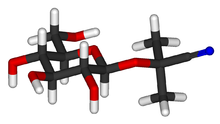

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.164.971 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C10H17NO6 | |

| Molar mass | 247.248 g/mol |

| Appearance | colorless needles [1] |

| Density | 1.41 g·cm−3 |

| Melting point | 143 to 144 °C (289 to 291 °F; 416 to 417 K)[1] |

| good [1] | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Linamarin is a cyanogenic glucoside found in the leaves and roots of plants such as cassava, lima beans, and flax. It is a glucoside of acetone cyanohydrin. Upon exposure to enzymes and gut flora in the human intestine, linamarin and its methylated relative lotaustralin can decompose to the toxic chemical hydrogen cyanide; hence food uses of plants that contain significant quantities of linamarin require extensive preparation and detoxification. Ingested and absorbed linamarin is rapidly excreted in the urine and the glucoside itself does not appear to be acutely toxic. Consumption of cassava products with low levels of linamarin is widespread in the low-land tropics. Ingestion of food prepared from insufficiently processed cassava roots with high linamarin levels has been associated with dietary toxicity, particularly with the upper motor neuron disease known as konzo to the African populations in which it was first described by Trolli and later through the research network initiated by Hans Rosling. However, the toxicity is believed to be induced by ingestion of acetone cyanohydrin, the breakdown product of linamarin.[2] Dietary exposure to linamarin has also been reported as a risk factor in developing glucose intolerance and diabetes, although studies in experimental animals have been inconsistent in reproducing this effect[3][4] and may indicate that the primary effect is in aggravating existing conditions rather than inducing diabetes on its own.[4][5]

The generation of cyanide from linamarin is usually enzymatic and occurs when linamarin is exposed to linamarase, an enzyme normally expressed in the cell walls of cassava plants. Because the resulting cyanide derivatives are volatile, processing methods that induce such exposure are common traditional means of cassava preparation; foodstuffs are usually made from cassava after extended blanching, boiling, or fermentation.[6] Food products made from cassava plants include garri (toasted cassava tubers), porridge-like fufu, the dough agbelima, and cassava flour.

Research efforts have developed a transgenic cassava plant that stably downregulates linamarin production via RNA interference.[7]

References

- ^ a b c Shmuel Yannai: Dictionary of Food Compounds with CD-ROM: Additives, Flavors, and Ingredients. CRC Press, 2003, ISBN 978-1-58488-416-3, P. 695

- ^ Banea-Mayambu JP, Tylleskar T, Gitebo N, Matadi N, Gebre-Medhin M, Rosling H. (1997). Geographical and seasonal association between linamarin and cyanide exposure from cassava and the upper motor neurone disease konzo in former Zaire. Trop Med Int Health 2(12):1143-51. PMID 9438470

- ^ Soto-Blanco B, Marioka PC, Gorniak SL. (2002). Effects of long-term low-dose cyanide administration to rats. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 53(1):37-41. PMID 12481854

- ^ a b Soto-Blanco B, Sousa AB, Manzano H, Guerra JL, Gorniak SL. 2001. Does prolonged cyanide exposure have a diabetogenic effect?. Vet Hum Toxicol. 43(2):106-8.

- ^ Yessoufou A, Ategbo JM, Girard A, Prost J, Dramane KL, Moutairou K, Hichami A, Khan NA. (2002). Cassava-enriched diet is not diabetogenic rather it aggravates diabetes in rats. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 20(6):579-86. PMID 17109651

- ^ Padmaja G. (1995). Cyanide detoxification in cassava for food and feed uses. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 35(4):299-339. PMID 7576161

- ^ Siritunga D, Sayre R (2003). "Generation of cyanogen-free transgenic cassava". Planta 217 (3): 367-73. doi:10.1007/s00425-003-1005-8 PMID 14520563