Li Cunxin

Li Cunxin | |

|---|---|

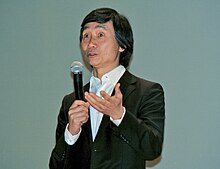

Li Cunxin in 2010 | |

| Born | 26 January 1961 |

| Spouse(s) |

Elizabeth Mackey

(m. 1981; div. 1987)Mary McKendry (m. 1987) |

| Children | 3 |

| Li Cunxin | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 李存信 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Li Cunxin AO (born 26 January 1961) is a Chinese-Australian former ballet dancer turned stockbroker. He is currently the artistic director of the Queensland Ballet in Brisbane, Australia.[2]

Life and career

Li was the sixth of seven brothers,[3] born into poverty in the Li Commune near the city of Qingdao in the Shandong province of the People's Republic of China. He often had to support his extremely poor family. Li's early life coincided with Mao Zedong's rule over the new Communist nation. Li had a strong desire to serve China's Communist Party. He was quite politically devout, eventually joining in the CCP's Youth League. At the age of eleven, he was chosen by Madame Mao's cultural advisors to attend the Beijing Dance Academy, where students had to undergo 16-hour-a-day training. He attended the Academy for seven years. The regime in Beijing Dance was harsh, starting each morning at 5:30. Li performed well in the politics class,[4] but did badly in ballet. This changed when he met Teacher Xiao, who had a passion for ballet. Xiao's passion influenced Li, and by the end of the seven years' training he became a very good dancer.[5][3]

Artistic Director of the Houston Ballet Ben Stevenson was teaching two semesters at the Beijing Dance Academy. He offered a full scholarship for two dancers to study at the Houston Ballet summer school and Li was chosen as one. (Li was one of the first students from the Beijing Dance Academy to go to the United States under financial support from the central government of the People's Republic of China.)[3]

After his study at the summer school, Li defected to the West. He was held in the Chinese Consulate in Houston, his defection creating headlines in America. He had begun a relationship with an aspiring American dancer, Elizabeth Mackey, and in 1981, they married so that Li could avoid deportation. After 21 hours of negotiations, and intervention by George Bush Sr. (U.S. Vice President at the time), Li was allowed to stay in the US as a free man, but his Chinese citizenship was revoked.[3][6]

Li subsequently danced with the Houston Ballet for sixteen years, during which he won two silver and a bronze medal at International Ballet Competitions. While dancing in London, he met ballerina Mary McKendry from Rockhampton, Australia. They married in 1987.[7] In 1995 they moved to Melbourne, Australia, with their two children. Li became a principal dancer with The Australian Ballet. McKendry and Li have three children: Sophie (1989) Thomas (1992) and Bridie (1997).[8]

In July 2012,[2] Li was named as Artistic Director of the Queensland Ballet.[9] Li established himself as a mainstay of Brisbane's cultural scene.[10] He was named Australian Father of the Year in 2009.[11]

In July 2016, Barbara Baehr and Robert Whyte from the Queensland Museum named a newly discovered spider species Maratus licunxini after Li Cunxin.[12] Dr Baehr said a Queensland Ballet performance of Li Cunxin's A Midsummer Night's Dream reminded her of the stunning mating display of the peacock spider. Li said he was honoured to have the spider named after him saying "having seen this incredible spider, the intricate mating dance, the fancy peacock markings, I can understand why Barbara would make a link with our ballet dancers."[13][14]

After 18 years off-stage, Cunxin returned for a one-off performance as Drosselmeyer, specially choreographed by Ben Stevenson,[15] in The Nutcracker for the Queensland Ballet, dancing again with his wife, Mary McKendry, with whom he last danced in this work 26 years ago in Houston.[16][17]

In the 2019 Birthday Honours, Cunxin was appointed officer (AO) of the Order of Australia for "distinguished service to the performing arts, particularly to ballet, as a dancer and artistic director".[18]

Career as a stockbroker

After arriving in Australia in 1995, when sidelined by a sprained ankle, Li occupied himself by gaining work experience with ANZ Securities and embarking on a three-year diploma course with the Australian Securities Institute. He had previously become interested in the stock market while in Houston. The Australian Ballet and ANZ Securities accommodated his desire to work at two professions simultaneously, dancing and stockbroking. On Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays he worked at the stockbroking firm from 7:30am till noon when he arrived at the Australian Ballet for rehearsals and to prepare for performances. He followed this routine for two years. He believed these were his best years as a dancer. "I got to a level I thought I would never reach, a fusion of technique and artistry. When I was younger I might have been better technically, but I was lacking artistic maturity." Li retired from ballet in 1999 at the age of 38 and joined Bell Potter Securities to establish its Asian desk.[19]

Mao's Last Dancer

In 2003 Li published his autobiography, Mao's Last Dancer. It has received numerous accolades, including the Australian Book of the Year award. In 2008, the children's version of this book, Mao's Last Dancer: The Peasant Prince (illustrated by Anne Spudvilas), won the Australian Publishers Association's Book of the Year for Younger Children[20] and the Queensland Premier's Literary Awards Children's Book Award.[21]

Mao's Last Dancer was adapted into a 2009 feature film of the same name by director Bruce Beresford and writer Jan Sardi, starring Chi Cao, Bruce Greenwood and Kyle MacLachlan.[22] At the São Paulo International Film Festival 2009 the film won Best Foreign Feature Film Audience Award (tied with Broken Embraces).

References

- ^ NG, David (20 August 2010). "'Mao's Last Dancer' follows Chinese defector Li Cunxin's odyssey". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ a b Queensland Ballet (2012). Li Cunxin returns to the stage as Queensland Ballet's new Artistic Director Archived 4 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d Mao's Last Dancer, Li Cunxin homepage

- ^ Li Cunxin (27 August 2010). "Mao's Last Dancer". HuffPost. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ Li Cunxin (24 March 2014). "My Day: Ballet director Li Cunxin". BBC News. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ Taylor, Christie (14 May 2004). "'Mao's last dancer' tells his story". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ Jillett, Neil (6 September 2003). "Dance of the peasant prince". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ Mao's Last Dancer film tie-in by Li Cunxin. Penguin Books Australia. ISBN 9780670073481.

- ^ Li Cunxin speaker profile, Saxton Speakers Bureau

- ^ Brisbane Times, 31 July 2014 [full citation needed]

- ^ "Mao's Last Dancer is Australia's top dad". Australian Associated Press. 28 August 2009. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ "New dancing spider named for dancing icon". Arts Queensland. 11 July 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ Mitchell-Whittington, Amy (11 July 2016). "Mao's last dancer Li Cunxin inspires name of peacock spider". Brisbane Times. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ "Dancing peacock spider named after Mao's Last Dancer, Queensland Ballet artistic director Li Cunxin". ABC News. 11 July 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ "The Nutcracker: Li brings his magic to a cracking chestnut" by Deborah Jones, The Australian, 12 December 2017.

- ^ "Mao's Last Dancer Li Cunxin makes ballet return in the Nutcracker after 18 years off stage" by Lesley Robinson, ABC News, 7 December 2017.

- ^ Gateley, Michelle (14 September 2017). "Mao's Last Dancer Li Cunxin and ballerina wife reunite on stage". The Morning Bulletin. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ Zhou, Naaman (10 June 2019). "Queen's birthday honours list recognises trailblazers Rosie Batty and Ita Buttrose". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ "From Mao to now, a dancer takes stock". The Age. 31 August 2003. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ "Brooks wins Book of the Year award". The Sydney Morning Herald. 15 June 2008. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ "Queensland Premier's Literary awards 2008 winners". Department of the Premier and Cabinet (Queensland). 17 September 2008. Archived from the original on 20 September 2008. Retrieved 17 September 2008.

- ^ Mao's Last Dancer at IMDb

Further reading

- Li Cunxin (2003). Mao's Last Dancer. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-02924-6.

External links

- Official website

- Family portrait

- Li Cunxin at IMDb

- Li Cunxin – Mao's Last Dancer on YouTube, public speaking engagement

- 1961 births

- Living people

- Chinese male ballet dancers

- Australian male ballet dancers

- Artistic directors

- Artists from Brisbane

- Australian people of Chinese descent

- Chinese defectors

- Maoist China

- People from Melbourne

- Artists from Qingdao

- Beijing Dance Academy alumni

- Officers of the Order of Australia

- 20th-century ballet dancers

- 21st-century ballet dancers