N-Nitrosodimethylamine

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

N,N-Dimethylnitrous amide | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.500 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| KEGG | |||

| MeSH | Dimethylnitrosamine | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 3382 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C2H6N2O | |||

| Molar mass | 74.083 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Yellow oil[1] | ||

| Odor | faint, characteristic[1] | ||

| Density | 1.005 g/mL | ||

| Boiling point | 153.1 °C; 307.5 °F; 426.2 K | ||

| 290 mg/ml (at 20 °C) | |||

| log P | −0.496 | ||

| Vapor pressure | 700 Pa (at 20 °C) | ||

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.437 | ||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Std enthalpy of

combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

1.65 MJ/mol | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |||

Main hazards

|

Known carcinogen[1], extremely toxic | ||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| Danger | |||

| H301, H330, H350, H372, H411 | |||

| P260, P273, P284, P301+P310, P310 | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | 61.0 °C (141.8 °F; 334.1 K) | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose)

|

37.0 mg/kg (oral, rat) | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible)

|

OSHA-Regulated Carcinogen[1] | ||

REL (Recommended)

|

Ca[1] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

Ca [N.D.][1] | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related compounds

|

|||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), also known as dimethylnitrosamine (DMN), is an organic compound with the formula (CH3)2NNO. It is one of the simplest members of a large class of N-nitrosamines. It is a volatile yellow oil. NDMA has attracted wide attention as being highly hepatotoxic and a known carcinogen in lab animals.[2]

Occurrence

Drinking water

Of more general concern, NDMA can be produced by water treatment by chlorination or chloramination. The question is the level at which it is produced. In the U.S. state of California, the allowable level is 10 nanograms/liter. The Canadian province of Ontario set the standard at 9 ng/L. The potential problem is greater for recycled water that can contain dimethylamine.[3] Further, NDMA can form or be leached during treatment of water by anion exchange resins.[4]

NDMA's contamination of drinking water is of particular concern due to the minute concentrations at which it is harmful, the difficulty in detecting it at these concentrations, and to the difficulty in removing it from drinking water. It does not readily biodegrade, adsorb, or volatilize. As such, it cannot be removed by activated carbon and travels easily through soils. Relatively high levels of UV radiation in the 200 to 260 nm range breaks the N–N bond and can thus be used to degrade NDMA. Additionally, reverse osmosis removes approximately 50% of NDMA.[5]

Cured meat

NDMA is found at low levels in numerous items of human consumption, including cured meat, fish, beer, tobacco smoke.[4][6] The pathway for NDMA formation involves nitrous acid produced from sodium nitrite, which is used to cure meat. NDMA arises by the combination of nitrous acid and dimethylamine derived from the degradation of protein (food) in the lower gut.

Rocket fuel

Unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine, a rocket fuel, is a highly effective precursor to NDMA:

- (CH3)2NNH2 + 2 O → (CH3)2NNO + H2O

Groundwater near rocket launch sites often has high levels of NDMA.[5]

Regulation

United States

The US Environmental Protection Agency has determined that the maximal admissible concentration of NDMA in drinking water is 7 ng/L.[7] The EPA has not yet set a regulatory maximal contaminant level (MCL) for drinking water. At high doses, it is a "potent hepatotoxin that can cause fibrosis of the liver" in rats.[8] The induction of liver tumors in rats after chronic exposure to low doses is well documented.[9] Its toxic effects on humans are inferred from animal experiments but not well-established experimentally.

It is classified as an extremely hazardous substance in the United States as defined in Section 302 of the U.S. Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (42 U.S.C. 11002) and is subject to strict reporting requirements by facilities that produce, store, or use it in significant quantities.[10]

It was found as an impurity in valsartan and other angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) used to treat high blood pressure and heart failure. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has confirmed levels of NDMA and/or NDEA exceeding the interim acceptable intake limits, and the affected medicines are being recalled as of November 2019.[11]

The FDA is also requesting makers of antacids that include ranitidine, such as Zantac, to recall their products because unacceptable levels of NDMA form in ranitidine over time, especially when these antacids are stored where it is warmer than room temperature.[12]

The FDA has further requested that the makers of Metformin recall their products because unacceptable levels of NDMA.[13]

Chemistry

The C2N2O core of NDMA is planar, as established by X-ray crystallography. The central nitrogen is bound to two methyl groups and the NO group with bond angles of 120°. The N-N and N-O distances are 1.32 and 1.26 Å, respectively.[14]

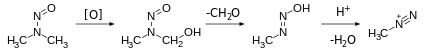

NDMA forms from a variety of dimethylamine-containing compounds, e.g. hydrolysis of dimethylformamide. Dimethylamine is susceptible to oxidation to unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine, which air-oxidizes to NDMA.[15]

In the laboratory, NDMA can be synthesised by the reaction of nitrous acid with dimethylamine:

- HONO + (CH3)2NH → (CH3)2NNO + H2O

The mechanism of its carcinogenicity involves metabolic activation steps resulting in the formation of methyl diazonium, an alkylating agent.[2]

As a poison

Several incidents in which NDMA was used to intentionally poison another person have garnered media attention. In 1978, a teacher in Ulm, Germany, was sentenced to life in prison for trying to murder his wife by poisoning jam with NDMA and feeding it to her. Both the wife and the teacher later died from liver failure.[16][17] Also in 1978, Steven Roy Harper spiked lemonade with NDMA at the Johnson family home in Omaha, Nebraska. The incident resulted in the deaths of 30-year-old Duane Johnson and 11-month-old Chad Shelton. For his crime, Harper was sentenced to death, but committed suicide in prison before his execution could be carried out.[18][full citation needed]

In the 2013 Fudan poisoning case, Huang Yang, a postgraduate medical student at Fudan University, was the victim of a poisoning in Shanghai, China. Huang was poisoned by his roommate Lin Senhao, who had placed NDMA into the water cooler in their dormitory. Lin claimed that he only did this as an April Fool's joke. He received a death sentence, and was executed in 2015.[19] In 2018, NDMA was used in an attempted poisoning at Queen's University in Kingston, Canada.[20]

Drug contamination

In 2018, and then again in late 2019, various brands of valsartan were recalled because of contamination with N-nitrosodimethylamine.[21] In 2019, ranitidine was recalled across the world due to contamination with NDMA.[22] In December 2019, the FDA began testing samples of the diabetes drug metformin for the carcinogen N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA). The FDA's announcement followed a recall of three versions of metformin in Singapore, and the European Medicines Agency's request that manufacturers test for NDMA.[23][24]

References

- ^ a b c d e f NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0461". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ a b c Tricker, A.R.; Preussmann, R. (1991). "Carcinogenic N-nitrosamines in the Diet: Occurrence, Formation, Mechanisms and Carcinogenic Potential". Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology. 259 (3–4): 277–289. doi:10.1016/0165-1218(91)90123-4. PMID 2017213.

- ^ "Sources and Fate of Nitrosodimethylamine and Its Precursors in Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants". Water Environment Research. 77 (1, Emerging Micropollutants in Treatment Systems (Jan.–Feb. 2005)): 32–39. 2005. doi:10.2175/106143005X41591. JSTOR 25045835.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b Najm, I.; Trussell, R. R. (2001). "NDMA Formation in Water and Wastewater". Journal American Water Works Association. 93 (2): 92–99. doi:10.1002/j.1551-8833.2001.tb09129.x. ISSN 0003-150X.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Mitch, W. A.; Sharp, J. O.; Trussell, R. R.; Valentine, R. L.; Alvarez-Cohen, L.; Sedlak, D. L. (2003). "N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) as a Drinking Water Contaminant: A Review". Environmental Engineering Science. 20 (5): 389–404. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.184.204. doi:10.1089/109287503768335896.

- ^ Hecht, Stephen S. (1998). "Biochemistry, Biology, and Carcinogenicity of Tobacco-Specific N-Nitrosamines†". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 11: 559–603. doi:10.1021/tx980005y. PMID 9625726.

- ^ Andrzejewski, P.; Kasprzyk-Hordern, B.; Nawrocki, J. (2005). "The hazard of N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) formation during water disinfection with strong oxidants". Desalination. 176 (1–3): 37–45. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2004.11.009.

- ^ George, J.; Rao, K. R.; Stern, R.; Chandrakasan, G. (2001). "Dimethylnitrosamine-induced liver injury in rats: the early deposition of collagen". Toxicology. 156 (2–3): 129–138. doi:10.1016/S0300-483X(00)00352-8. PMID 11164615.

- ^ Peto, R.; Gray, R.; Brantom, P.; Grasso, P. (1991). "Dose and Time Relationships for Tumor Induction in the Liver and Esophagus of 4080 Inbred Rats by Chronic Ingestion of N-Nitrosodiethylamine or N-Nitrosodimethylamine" (PDF). Cancer Research. 51 (23 Part 2): 6452–6469. PMID 1933907.

- ^ "40 C.F.R.: Appendix A to Part 355—The List of Extremely Hazardous Substances and Their Threshold Planning Quantities" (PDF) (July 1, 2008 ed.). Government Printing Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2012. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "FDA Updates and Press Announcements on Angiotensin II Receptor Blocker (ARB) Recalls (Valsartan, Losartan, and Irbesartan)". Drug Safety and Availability. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. November 7, 2019. Retrieved November 15, 2019.

- ^ Ed Silverman (2020), "FDA Asks Manufacturers to Recall Heartburn Drugs over Traces of a Possible Carcinogen", STAT, April 1, 2020, http://statnews.com . Accessed 2020 April 1.

- ^ Associated Press (2020), "FDA finds contamination in diabetes drug across several brands", May 29, 2020, https://www.foxbusiness.com/lifestyle/fda-finds-contamination-in-several-brands-of-diabetes-drug . Accessed 2020 May 29.

- ^ Krebs, Bernt; Mandt, Jürgen (1975). "Kristallstruktur des N-Nitrosodimethylamins". Chemische Berichte. 108 (4): 1130–1137. doi:10.1002/cber.19751080419.

- ^ Mitch, William A.; Sedlak, David L. (2002). "Formation of N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) from Dimethylamine during Chlorination". Environmental Science & Technology. 36 (4): 588–595. Bibcode:2002EnST...36..588M. doi:10.1021/es010684q.

- ^ Ein teuflischer Plan: Tod aus dem Marmeladeglas (in German).

- ^ Karsten Strey: "Die Welt der Gifte", Lehmanns, 2. Edition p. 193 (in German).

- ^ Roueche, Betron (January 25, 1982). "Annals of Medicine – The Prognosis for this Patient is Horrible". The New Yorker: 57–71.[full citation needed]

- ^ "15 days log in hospital". Archived from the original on 2014-01-09. Retrieved 2013-04-30.

- ^ https://www.thewhig.com/news/local-news/man-admits-poisoning-fellow-researcher-in-kingston?

- ^ EMA Staff (September 17, 2018). "EMA reviewing medicines containing valsartan from Zhejiang Huahai following detection of an impurity: some being recalled across the EU". European Medicines Agency. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ BBC Staff (September 29, 2019). "Sale of heartburn drug suspended over cancer fears". BBC News. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ Lauerman, John (December 4, 2019). "Diabetes Drugs Latest to Be Targeted for Carcinogen Scrutiny". Bloomberg Business. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Koenig, D. (December 6, 2019). "FDA Investigating Metformin for Possible Carcinogen". Medscape. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

External links

- Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) Information

- CDC - NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- Method Development for the Determination of N-Nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA) in Drinking Water

- SFPUC NDMA White Paper

- Public Health Statement for n-Nitrosodimethylamine

- Toxicological Profile for n-Nitrosodimethylamine CAS# 62-75-9