Our World in Data

Our World in Data (OWID) is a scientific online publication that focuses on large global problems such as poverty, disease, hunger, climate change, war, existential risks, and inequality.[1]

The publication's founder is the social historian and development economist Max Roser. The research team is based at the University of Oxford.[2]

Mission and content

The mission of Our World in Data is to present "research and data to make progress against the world’s largest problems".[3]

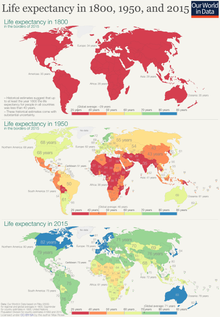

The web publication on global development uses interactive data visualizations (charts and maps) to present the research findings on development that explain the causes and consequences of the observed changes. The aim is to show how the world is changing and why.

Our World in Data covers a wide range of topics across many academic disciplines: Trends in health, food provision, the growth and distribution of incomes, violence, rights, wars, culture, energy use, education, and environmental changes are empirically analyzed and visualized in this web publication.

It often takes a long-term view to show how global living conditions have changed over the last centuries.

Covering all of these aspects in one resource makes it possible to understand how the observed long-run trends are interlinked. The research on global development is presented to the audience of interested readers, journalists, academics, and policy people. The articles cross-reference each other to make it possible for the reader to learn about the drivers of the observed long-run trends. For each topic the quality of the data is discussed and, by pointing the visitor to the sources, this website works as a database of databases – a meta-database.[4]

Our World in Data published a sister project called SDG-Tracker.org that presents all available data on the 232 SDG-Indicators with which the 17 Sustainable Development Goals are assessed.

In 2020, Our World in Data became one of the leading organizations publishing global data and research on the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.[5]

History

Roser started to work on Our World in Data in 2011.[6] During the first years he financed his project as a bicycle tour guide around Europe. Only later did he establish a research team at the University of Oxford that is studying global development.

In the first years Roser developed the publication together with inequality researcher Sir Tony Atkinson. The first grant to support the research project was given by the Nuffield Foundation, a London-based foundation focused on social policy. When the project ran out of funding it was rescued by the "Save OurWorldInData.org“ crowdsourcing campaign.[7]

Until 2015 the project was built in "nights and weekends" by Roser. Only later was it developed into a research project at the University of Oxford.

Infographics of Our World in Data, shared by Bill Gates in early 2019, show the history of human progress over the past 200 years.[8]

In 2014 the site was read by 120,000 readers.[9] Since then the number of readers increased. Between December 2018 and 2019 the site was read by more than 25 million readers.[10] Our World in Data is most widely used in the anglophone world.

In early 2019, Our World in Data was one of only 3 nonprofit organizations in Y Combinator's Winter 2019 cohort.[11][12]

In 2019 Tyler Cowen and Patrick Collison called for a new academic discipline of 'Progress Studies' that institutionalizes the mission of Our World in Data and Collison published a permanent recommendation to join the team of Our World in Data.[13][14]

In 2019 Our World in Data won the Lovie Award, the European web award, "in recognition of their outstanding use of data and the internet to supply the general public with understandable data-driven research – the kind necessary to invoke social, economic, and environmental change."[15]

Publishing model

Our World in Data is one of the largest scientific open-access publications. It is made available as a public good:

- The entire publication is freely available.

- All data published on the website is available for download.

- All visualizations created for the web publication are made available under a Creative Commons license.

- And all tools developed to publish Our World in Data and to create the visualizations are free to use (available open source on GitHub).[16]

The team developed the Our World in Data-Grapher, a combination of database and visualization tool. The database includes more than 70,000 variables.[17]

Collaborations and partnerships

The Our World in Data team partnered with several organizations:

The publication has received grants from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Nuffield Foundation as well as donations from hundreds of individuals.[18]

The non-profit Global Change Data Lab publishes the website and the open-access data tools that make the online publication possible. The research team is based at the University of Oxford's Oxford Martin School. Director is the founder Max Roser.[19]

The Our World in Data research team also publishes their research work in a number of widely accessed media outlets including the BBC,[20] Vox, The New York Times, The Guardian, and The Washington Post. The research team has also collaborated with science YouTube channel Kurzgesagt to reach millions of viewers.

The team's head of research is Dr Hannah Ritchie.

Usage

Research from Our World in Data is used in many ways:

Our World in Data is cited in academic scientific journals like Science,[21] Nature,[22][23][24] and PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences).[25]

In medicine and global health journals like the British Medical Journal[26] or The Lancet[27] and in social science journals like the Quarterly Journal of Economics[28] Our World in Data has been cited.

The website is used widely in the media.[29] The BBC[30] and publications like The Washington Post, The New York Times,[31] and The Economist[32] regularly rely on Our World in Data as a source.

Tina Rosenberg emphasized in The New York Times that Our World in Data presents a “big picture that’s an important counterpoint to the constant barrage of negative world news”. Steven Pinker placed Roser's Our World in Data on his list of his personal “cultural highlights”[33] and explained in his article on 'the most interesting recent scientific news' why he considers Our World in Data so very important.[34]

Private sector companies, like McKinsey Consulting, rely on Our World in Data publications to understand emerging markets and changes in poverty and prosperity.[35][36]

Many authors and researchers rely on Our World in Data for their work: these include[37] David Spiegelhalter, Wali Zahid, Harini Nagendra, William MacAskill, Harini Nagendra, John Green, Tim O’Reilly, Andrew Revkin, Steven Pinker, Joia Mukherjee, Sibylle Berg, Alice Evans, Tim Harford, George Monbiot, Michael Levitt, Kelsey Piper,[38] Patrick Webb, Scott Alexander,[39] John Cassidy, Ruth DeFries, Paul Krugman and Steven Berlin Johnson.

Institutions that rely on this online publication for their teaching include Harvard, the University of Oxford, Stanford University, the University of Chicago, The University of Cambridge, and the University of California Berkeley.[40] Our World in Data is used by teachers and lecturers in a range of subjects including medicine, psychology, biology, sustainable development, economics, history, politics and public policy.

In many parts of the world the research of Our World in Data is the top search result for topics the research team has worked on. These include ‘CO2 emissions’, ‘world poverty’, ‘child mortality’, and ‘population growth’.

See also

References

- ^ "About". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2019-08-23.

- ^ "The Oxford Martin Programme on Global Development". Oxford Martin School. Retrieved 2019-06-05.

- ^ "Our World in Data". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2019-08-23.

- ^ "About — Our World in Data". ourworldindata.org. Retrieved 2016-03-08.

- ^ "Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19)". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- ^ "History of Our World in Data". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2019-10-29.

- ^ "History of Our World in Data". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2019-11-02.

- ^ Gallo, Carmine. "Bill Gates Shares His 'Favorite Infographic' That Shows 200 Years Of Human Progress". Forbes. Retrieved 2019-02-05.

- ^ "History of Our World in Data". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ "How many visitors ourworldindata.org got in the last 12 months". www.visitorsdetective.com. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

- ^ "YC-backed Our World in Data wants you to know what's changing about the planet". TechCrunch. Retrieved 2019-01-23.

- ^ "Our World in Data is at Y Combinator". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- ^ "Work · Patrick Collison". patrickcollison.com. Retrieved 2019-09-22.

- ^ Cowen, Patrick Collison, Tyler (2019-07-30). "We Need a New Science of Progress". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2019-09-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Meet The 2019 Lovie Awards Special Achievement Winners". The Lovie Awards. 2019-10-07. Retrieved 2019-11-02.

- ^ "OurWorldInData/our-world-in-data-grapher". GitHub. Retrieved 2016-03-09.

- ^ "History of Our World in Data". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2019-11-02.

- ^ "Our supporters". OWID. Retrieved 2019-01-23.

- ^ "Our Team". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2019-06-18.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah (2019-02-04). "Which countries eat the most meat?". Retrieved 2019-06-05.

- ^ Nagendra, Harini; DeFries, Ruth (2017-04-21). "Ecosystem management as a wicked problem". Science. 356 (6335): 265–270. doi:10.1126/science.aal1950. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 28428392.

- ^ Lamentowicz, M.; Kołaczek, P.; Laggoun-Défarge, F.; Kaliszan, K.; Jassey, V. E. J.; Buttler, A.; Gilbert, D.; Lapshina, E.; Marcisz, K. (2016-12-20). "Anthropogenic- and natural sources of dust in peatland during the Anthropocene". Scientific Reports. 6: 38731. doi:10.1038/srep38731. PMC 5171771. PMID 27995953.

- ^ Topol, Eric J. (2019). "High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence". Nature Medicine. 25 (1): 44–56. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0300-7. ISSN 1546-170X. PMID 30617339.

- ^ Liu, Xin; Xu, Xun; Vigouroux, Yves; Wettberg, Eric von; Sutton, Tim; Colmer, Timothy D.; Siddique, Kadambot H. M.; Nguyen, Henry T.; Crossa, José (May 2019). "Resequencing of 429 chickpea accessions from 45 countries provides insights into genome diversity, domestication and agronomic traits" (PDF). Nature Genetics. 51 (5): 857–864. doi:10.1038/s41588-019-0401-3. ISSN 1546-1718. PMID 31036963.

- ^ Levitt, Jonathan M.; Levitt, Michael (2017-06-20). "Future of fundamental discovery in US biomedical research". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (25): 6498–6503. doi:10.1073/pnas.1609996114. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5488913. PMID 28584129.

- ^ Lartey, Anna; Shetty, Prakash; Wijesinha-Bettoni, Ramani; Singh, Sudhvir; Stordalen, Gunhild Anker; Webb, Patrick (2018-06-13). "Hunger and malnutrition in the 21st century". BMJ. 361: k2238. doi:10.1136/bmj.k2238. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 5996965. PMID 29898884.

- ^ Yamin, Alicia Ely; Uprimny, Rodrigo; Periago, Mirta Roses; Ooms, Gorik; Koh, Howard; Hossain, Sara; Goosby, Eric; Evans, Timothy Grant; DeLand, Katherine (2019-05-04). "The legal determinants of health: harnessing the power of law for global health and sustainable development". The Lancet. 393 (10183): 1857–1910. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30233-8. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 31053306.

- ^ Weil, David; Storeygard, Adam; Squires, Tim; Henderson, J. Vernon (2018-02-01). "The Global Distribution of Economic Activity: Nature, History, and the Role of Trade". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 133 (1): 357–406. doi:10.1093/qje/qjx030. ISSN 0033-5533. PMC 6889963. PMID 31798191.

- ^ "Media Coverage of OurWorldInData.org — Our World in Data". ourworldindata.org. Archived from the original on 2015-11-04. Retrieved 2016-03-08.

- ^ "Why income inequality is so much worse in the U.S. than in other rich countries". Washington Post.

- ^ Frakt, Austin (2018-05-14). "Medical Mystery: Something Happened to U.S. Health Spending After 1980". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-06-05.

- ^ "Africa is on track to be declared polio-free". The Economist. 2019-08-21. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2019-11-03.

- ^ Observer, Steven Pinker/the (2015-08-23). "On my radar: Steven Pinker's cultural highlights". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-03-08.

- ^ "Human Progress Quantified – Edge answer by Steven Pinker". www.edge.org. Retrieved 2016-03-08.

- ^ "Tech for Good". Mc Kinsey Global Institute.

- ^ "Chris Blattman blog". Chris Blattman. Retrieved 2016-03-08.

- ^ "Our Audience & Coverage". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- ^ Piper, Kelsey (2019-08-20). "We've worried about overpopulation for centuries. And we've always been wrong". Vox. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- ^ Alexander, Scott (2019-04-23). "1960: The Year The Singularity Was Cancelled". Slate Star Codex. Retrieved 2019-12-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Our World in Data for teaching – what we are learning from your feedback". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2019-06-05.