Battle of Athens (1946)

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Battle of Athens | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

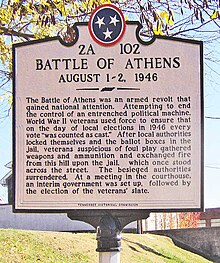

THC marker at the "Battle of Athens" site | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Local World War II veterans and other citizens | McMinn County Sheriff's Department | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Bill White James Buttram Knox Henry Frank Charmichael George Painter Charles Picket E. R. Self |

Pat Mansfield Boe Dunn Paul Cantrell | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Some injuries, no fatalities | Many injuries, some severe, no fatalities | ||||||

The Battle of Athens (sometimes called the McMinn County War) was a rebellion led by citizens in Athens and Etowah, Tennessee, United States, against the local government in August 1946. The citizens, including some World War II veterans, accused the local officials of predatory policing, police brutality, political corruption, and voter intimidation.

Background

In 1936, the E. H. Crump political machine based in Memphis, which controlled much of Tennessee, extended to McMinn County with the introduction of Paul Cantrell as the Democratic candidate for sheriff.[1] Cantrell, who came from a family of money and influence in nearby Etowah, tied his campaign closely to the popularity of the Roosevelt administration and rode FDR's coattails to victory over his Republican opponent in what came to be known as "vote grab of 1936" which delivered McMinn County to Tennessee's Crump Machine.[1] Paul Cantrell was elected sheriff in the 1936, 1938, and 1940 elections, and was elected to the state senate in 1942 and 1944, while his former deputy, Pat Mansfield, a transplanted Georgian, was elected sheriff.[1] A state law enacted in 1941 reduced local political opposition to Crump's officials by reducing the number of voting precincts from 23 to 12 and reducing the number of justices of the peace from fourteen to seven (including four "Cantrell men").[2] The sheriff and his deputies were paid under a fee system whereby they received money for every person they booked, incarcerated, and released; the more arrests, the more money they made.[2] Because of this fee system, there was extensive "fee grabbing" from tourists and travelers.[3] Buses passing through the county were often pulled over and the passengers were randomly ticketed for drunkenness, regardless of their intoxication or lack thereof.[2] Between 1936 and 1946, these fees amounted to almost $300,000.[3]

Citizens of McMinn County had long been concerned about political corruption and possible election fraud though some of the complaints, especially at first, may have been partisan carping.[2][4][non-primary source needed] The U.S. Department of Justice had investigated allegations of electoral fraud in 1940, 1942, and 1944, but had not taken action.[2] Voter fraud and vote control perpetuated McMinn County's political problems.[need quotation to verify] Manipulation of the poll tax and vote counting were the primary methods, but it was common for dead voters' votes to appear in McMinn County elections.[3] The political problems were further entrenched by economic corruption of political figures enabled by the gambling and bootlegging they permitted. Most of McMinn County's young men were fighting in World War II, allowing appointment of some ex-convicts as deputies.[3] These deputies furthered the political machine's goals and exerted control over the citizens of the county.[3] While the machine controlled the law enforcement, its control also extended to the newspapers and schools. When asked if the local newspaper, the Daily Post-Athenian, supported the GIs, veteran Bill White, replied: "No, they didn't help us none." White elaborated: "Mansfield had complete control of everything, schools and everything else. You couldn't even get hired as a schoolteacher without their okay, or any other job."[5]

During the war, two service men on leave were shot and killed by Cantrell supporters.[3] The servicemen of McMinn County heard of what was going on and were anxious to get home and do something about it. According to a contemporaneous article by Theodore H. White in Harper's Magazine, one veteran, Ralph Duggan, who had served in the Pacific in the Navy and became a leading lawyer in the postwar period, "thought a lot more about McMinn County than he did about the Japs. If democracy was good enough to put on the Germans and the Japs, it was good enough for McMinn County, too!"[3] The scene was ripe for a confrontation when McMinn County's GIs were demobilized. When they arrived home the deputies targeted the returning GIs, one reported: "A lot of boys getting discharged [were] getting the mustering out pay. Well, deputies running around four or five at a time grapping [sic] up every GI they could find and trying to get that money off of them, they were fee grabbers, they wasn't on a salary back then."[6][non-primary source needed]

In the August 1946 election, Paul Cantrell ran again for sheriff, while Pat Mansfield ran for the State Senate seat. Stephen Byrum, a local history author, speculates that the reason for this switch was an attempt to spread the graft among themselves.[3] Bill White, meanwhile, claims the reason for the swap was because they thought Cantrell stood a better chance running against the GIs.[7][non-primary source needed] The GIs were motivated more by hostility towards Sheriff Mansfield and his deputies rather than against Cantrell whose period as sheriff had been relatively benign.[8][non-primary source needed]

McMinn County had around 3,000 returning military veterans, constituting almost 10 percent of the county population. Some of the returning veterans resolved to challenge Cantrell's political control by fielding their own nonpartisan candidates and working for a fraud-free election. A meeting was called in May; veteran ID was required for admission. A non-partisan slate of candidates was selected.[9]

Veteran Bill White described the veterans' motivation:

There were several beer joints and honky-tonks around Athens; we were pretty wild; we started having trouble with the law enforcement at that time because they started making a habit of picking up GIs and fining them heavily for most anything—they were kind of making a racket out of it. After long hard years of service—most of us were hard-core veterans of World War II—we were used to drinking our liquor and our beer without being molested. When these things happened, the GIs got madder—the more GIs they arrested, the more they beat up, the madder we got ....[2]

The members of the GI Non-Partisan League were very careful to make their list of candidates match the demographics of the county, three Republicans and two Democrats.[10][11] A respected and decorated veteran of the North African campaign, Knox Henry, stood as candidate for sheriff in opposition to Cantrell.[2]

Large contributions made by local businessmen to the GIs' campaign ensured that it was well-funded, although many of McMinn County's citizens believed the machine would rig the election. The veterans capitalized on this belief with the slogan "Your Vote Will Be Counted As Cast."[9]

Well aware of the methods of Sheriff Mansfield and his associates, the League organized a counterpoise. A "fightin' bunch" was organized by Bill White "to keep the thugs from beating up GIs and keep them from taking the election."[12][non-primary source needed] White created his organization carefully; he later recalled: "I got out and started organizing with a bunch of GIs. Well spirits—I learned that you get the poor boys out of poor families, and the ones that was frontline warriors that's done fighting and didn't care to bust a cap on you. I learned to do that. So that's what I picked. I had thirty men and ... I took what mustering out pay I got and bought pistols. And some of them had pistols. I had thirty men organized".[12][non-primary source needed] Sheriff Mansfield also organized for the upcoming election, hiring 200 deputies, most from neighboring counties, some from out of state, at $50 a day (equivalent to $781 in 2023).[2]

Initial confrontations

Water Works polling place

Polls for the county election opened August 1, 1946. Normally, there were about 15 patrolmen on duty for the precincts, but about 200 armed deputies were on patrol for the election, with many of these reinforcements from other counties and states. In Etowah, a GI poll watcher requested a ballot box to be opened and certified as empty. Although he was allowed by law to make the request, he was arrested and taken to jail. In Athens, Walter Ellis protested irregularities in the election and was also arrested and charged with what was explained to him as a "federal offense".[9]

Around 3:00 p.m. local time, C.M. "Windy" Wise, a patrolman, prevented an elderly African American farmer, Tom Gillespie, from casting his ballot at the Athens Water Works polling place. When Gillespie and a GI poll watcher objected, Wise struck Gillespie with brass knuckles, which caused Gillespie to drop his ballot and run away from the deputy. Wise then pulled his pistol and shot Gillespie in the back.[2][9]

Wise was the only person to face charges from the events of August 1–2, 1946, and was sentenced to 1–3 years in prison.[11]

Response

GIs gathered in front of L.L. Shaefer's store which was used as an office by campaign manager Jim Buttram.[2] Buttram had telegraphed Governor McCord in Nashville and U.S. Attorney General Tom Clark asking for help in ensuring a lawful election, but received no response.[2] When the group learned that Sheriff Mansfield had sent armed guards to all polling places, they convened at the Essankay Garage where they decided to arm themselves.[2]

Sheriff Mansfield arrived at the Water Works and ordered the poll closed. In the commotion that followed, Wise and Karl Nell, the deputies inside the Water Works, took two poll watchers, Charles Scott and Ed Vestal, captive. By one account, Scott and Vestal jumped through a glass window and fled to the safety of the crowd while Wise followed behind.[2] By another account there was a guns-drawn confrontation between Jim Buttram, who was accompanied by Scott's father, and Sheriff Mansfield. A third account argues that when Neal Esminger from the Daily Post-Athenian showed up to get a vote count, his entrance was a distraction that allowed Scott and Vestal to break through a door and escape. In any case, the escape was followed by gunfire which sent the crowd diving for cover.[9]

Someone in the crowd yelled, "Let's go get our guns," causing the crowd to head for the Essankay Garage. Deputy Chief Boe Dunn took the two deputies and the ballot box to the jail.[2] Two other deputies were dispatched to arrest Scott and Vestal. These deputies were disarmed and detained by the GIs, as were a set of reinforcements. GI advisor, Republican Election Commissioner and Republican Party Chairman, Otto Kennedy, asked Bill White what he was going to do. White said, "I don't know Otto; we might just kill them." According to White, Kennedy grew alarmed and announced "Oh Lord, oh Lord, oh Lord! No! I'm not having nothing else to do with this. Me and my brother and son-in-law is leaving here."[13] Lones Selber in American Heritage magazine says Kennedy "left, vowing to have no part in murder."[2] The crowd and most GIs left. The remaining GIs took the seven deputies-turned-hostages to a woods ten miles from Athens, stripped them, tied them to a tree and beat them.[2][13]

Twelfth Precinct Polling Place

At the twelfth precinct the GI poll watchers were Bob Hairrell and Leslie Doolie, a one-armed veteran of the North African theater. The polling place was commanded by Mansfield man Minus Wilburn. Wilburn tried to let a young woman vote, who Hairrell believed was underage, and had no poll tax receipt and was not listed in the voter registration.[9] Hairrell grabbed Wilburn's wrist when he tried to deposit the ballot in the box. Wilburn struck Hairrell on the head with a blackjack and kicked him in the face. Wilburn closed the precinct and took the GIs and ballot box across the street to the jail.[2] Hairrell was brutally beaten and was taken to the hospital.[9]

In response to cussing and taunts from the deputies, and the actions so far that day, Bill White, leader of the "fighting bunch," told his lieutenant Edsel Underwood to take 5 or 6 men and break into the National Guard Armory to steal weapons. The GIs took the front door keys from the caretaker and entered the building. They then armed themselves with sixty .30-06 Enfield rifles, two Thompson sub-machine guns and ammo. Lones Selber says White went for the guns himself.[2] Bill White then distributed the rifles and a bandoleer of ammo to each of the 60 GIs.[14][non-primary source needed]

Polls closing

As the polls closed, and counting began (sans the three boxes taken to the jail), the GI-backed candidates had a 3 to 1 lead.[2][9][15] When the GIs heard the deputies had taken the ballot boxes to the jail, Bill White exclaimed, "Boy, they doing something. I'm glad they done that. Now all we got to do is whip on the jail."[14]

The GIs recognized that they had broken the law, and that Cantrell would likely receive reinforcements in the morning, so the GIs felt the need to resolve the situation quickly.[16] The deputies knew little of military tactics, but the GIs knew them well. By taking up the second floor of a bank across the street from the jail, the GIs were able to reciprocate any shots from the jail with a barrage from above.[16]

By 9:00 PM, Paul Cantrell, Pat Mansfield, George Woods (Speaker of the State House of Representatives and Secretary of the McMinn County Election Commission), and about 50 deputies were in the jail, allegedly rummaging through the ballot boxes. Woods and Mansfield constituted a majority of the election commission and could therefore certify and validate the count from within the jail.[16]

Battle

Estimates of the number of veterans besieging the jail vary from several hundred[15] to as high as 2,000.[11] Bill White had at least 60 under his command. White split his group with Buck Landers taking up position at the bank overlooking the jail while White took the rest by the Post Office.[14][non-primary source needed]

Just as the estimates of people involved vary widely, accounts of how the Battle of Athens began and its actual course disagree.

Egerton and Williams recall that when the men reached the jail, it was barricaded and manned by 55 deputies. The veterans demanded the ballot boxes but were refused. They then opened fire on the jail, initiating a battle that lasted several hours by some accounts,[11][15] considerably less by others.[17]

As Lones Selber, author of the 1985 American Heritage magazine article wrote: "Opinion differs on exactly how the challenge was issued." White says he was the one to call it out: "Would you damn bastards bring those damn ballot boxes out here or we are going to set siege against the jail and blow it down!" Moments later the night exploded in automatic weapons fire punctuated by shotgun blasts. "I fired the first shot," White claimed, "then everybody started shooting from our side." A deputy ran for the jail. "I shot him; he wheeled and fell inside of the jail."[2]

In 2000 Bill White claimed he said "Boys, ... I'm going to tell them to bring the ballot box out of there, and if they don't we're gonna open up on them.' I hollered in there, I said, 'You damn thieve grabbers, bring them damn ballot boxes out of there.' 'That's just what I said. He didn't make a move down there and finally one of them said, 'By God I heard a bolt click.' Down there—one of them grabbers did, you know—they started scattering around. And I had a pistol in my belt with a shotgun. I had a shotgun and a rifle. And I pulled the pistol out and started firing down there at them. Well, when I did that, all that whole line up there started firing down there in there. A lot of them got in the jail, some of them didn't, some of them got shot laying outside. And the battle started."[14]

Byrum wrote in 1984 that there was a volley of fire that lasted for "several hours," although gives no exact time for the end of hostilities or an account of the course of the battle. He noted that the deputies surrendered at 3:30 AM.[16]

The day after the battle, the New York Times front page reported a sheriff had been killed, and that the shooting had started with a shot through a jail window and with the demand the hostages be released. Then the Times reported the deputies refused and the siege ensued. The account followed, revealing the Times's source as Lowell F. Arterburn, publisher of The Athens Post Athenian. Arterburn reported shots being fired, 2,000 persons milling around, and "at least a score of fist fights were in progress."[18]

An attempt by deputies outside the jail to reinforce (or take refuge in) the jail was thwarted by Bill White's "fighting band". Some people in the jail managed to escape out the back door.[14][non-primary source needed] The fleeing people threw down their weapons and ran off, so White ordered his forces not to shoot the escapees.[19] One of the escapees was George Woods who had telephoned Birch Biggs, the boss of next door Polk County, requesting that Biggs send reinforcements to break the siege. Biggs replied "Do you think I'm crazy?"[2]

For the veterans it was either win before morning or face a long time in jail for violating local, state, and federal laws.[16] Rumors spread that the National Guard or state troopers were coming.[2] White made hourly demands for surrender. The GIs attempted to bombard the jail with Molotov cocktails but were not able to throw them far enough to reach the jail.[14] The GIs decided to resort to dynamite. At about that time an ambulance pulled up to the jail. The GIs assumed it was called to remove the wounded and held fire. Two men jumped in, and it sped off carrying Paul Cantrell and Sheriff Mansfield to safety out of town.[2]

Then the dynamite was deployed. Bill White said, "We'd put two or three sticks of dynamite together and tape it together and put a cap in there and a fuse. And we'd rear back and throw them. Well, we couldn't get them all the way to the jail, but we got them out to them cars. They'd blow them cars up in the air and turn them over and land them back on the top. Several cars down there were blowing up."[19] That first bomb landed under Bob Dunn's cruiser, flipping it on its back.[2] Bill White, commander of the "fighting bunch" knew the GIs had to do better: "I ... said, 'We're going to have to get some charges up there on that jail.' I said, 'Make a couple charges there.... We'll go down there and we'll place some charges.' So I made up a couple charges and I crawled up and put a charge on the jailhouse porch."[19] In fact three bombs went off almost simultaneously. One destroyed Mansfield's car, one landed on the jail porch roof, and one went off against the jail wall. The bombs caused some damage to the jail and scattered debris.[2]

As with the beginning of the battle accounts of the end differ: American Heritage states, "In the end, the door of the jail was dynamited and breached. The barricaded deputies—some with injuries—surrendered, and the ballot boxes were recovered."[2]

The New York Times observed in an article the night was "bloody" and that it ended after the GIs detonated 3 "home-made demolition charges."[20]

End of the battle and vote counting

Byrum reported the end of the battle thusly: "By 3:30 a.m., the men holding the jail had been dynamited into submission, and by early morning George Woods was calling Ralph Duggan to ask if he could come to Athens and certify the election of the GI slate. Bill White reported that "when the GIs broke into the jail, they found some of the tally sheets marked by the machine had been scored fifteen to one for the Cantrell forces." When the final tally was completed, Knox Henry was elected.[16]

During the fight at the jail, rioting had broken out in Athens, mainly targeting police cars.[11][15] This continued after the ballot boxes were recovered, but subsided by morning.[17] The mob also destroyed automobiles of the deputies, many bearing out-of-state plates.[20] During the disorder the Mayor of Athens was on vacation and the city policemen were "nowhere to be found."[21]

The morning of August 2 found the town quiet. Some minor acts of revenge happened, but the public mood was one of "euphoria that had not been experienced in McMinn County in a long time."[22] Governor McCord initially moved to activate the National Guard but quickly rescinded the order.[21] The morning saw the GIs call a meeting. GI Non-Partisan League Treasurer Harry Johnson opened the meeting observing it was necessary because "for some reason or other, the Sheriff's force is not around."[20] The approximately 400 persons in the court room elected a special committee headed by Methodist minister Bernie Hampton, joined by C.A. Anderson and Gobo Cartwright, both members of the Business Men's Evangelical Committee, to preserve law and order. George Woods, the escaped Secretary of the County Election Commission, sent a written missive saying: "Next Monday at 10 A.M. I will sign an election certificate certifying that the GI ticket was elected." Later the veterans turned responsibility for maintaining order in Athens to Police Chief Herbert Walker. The GIs said they were still "holding control" of McMinn County until September 1 when Knox Henry was to be installed as sheriff.[20]

August 2 also saw the return to McMinn County of Sheriff-elect Knox Henry, who had spent the night of August 1–2 in safe keeping in the Sweetwater jail. Sheriff Henry, a 33-year-old former Army Air Force Sergeant, observed "They were going to kill me yesterday, and I had to leave town."[20]

Nearby conflicts

In adjacent Meigs County, another use of weapons to effect electoral change occurred. On August 5 the Meigs County Election Commission certified Republican Oscar Womac as sheriff. Womac admitted to a reporter that he had ordered some associates to burn "a bunch of ballots." The ballots, he claimed, were found in the Meigs County Courthouse the previous day. It was reported in The Chattanooga Times that Sheriff J.T. Pettit claimed the Peakland ballot box was taken at gun-point by Womac and companions from the County Clerk's office the day before the ballot burning. "There was little we could do to stop him, he was armed, and the four men with him were armed," Sheriff Pettit said.[23] In Monroe County, east of McMinn County and north of Polk County, 65 year old county sheriff Jake Tipton was shot and killed during a dispute at the Vale precinct.[24]

Aftermath

The recovered ballots certified the election of the five GI Non-Partisan League candidates.[17] Among the reforms instituted was a change in the method of payment and a $5,000 salary cap for officials. In the initial momentum of victory, gambling houses in collusion with the Cantrell regime were raided and their operations demolished. Deputies of the prior administration resigned and were replaced.[17]

The ballots, when tallied, proved a landslide for the GI Non-Partisan League. Scores of veterans were present when Speaker of the state House of Representatives and secretary of the McMinn County election commissioners George Woods was marched into the County Courthouse under the guard of ex-GIs. Speaker Woods had fled after the gun battle.[23] League member Knox Henry received 2,175 against 1,270 for Sheriff Cantrell. The League also won the other races: 2,194 to 1,270 for Frank Carmichael as trustee; George Painter won the county clerk race 2,175 to 1,198; the circuit court clerk broke 2,165 to 1,197 for Charles Picket.[23]

Bill White, leader of the "fighting bunch," was made a sheriff's deputy. "They put me in as a deputy. Because, one of the reasons they put me in as deputies was to scare them GIs. (Laughs) They wanted me to control the GIs. Which they did—they fired into them people's houses and everything else. And that was my job to get out there and keep the GIs straight. And I did. I had sixteen fights in one weekend. Fighting GIs, keeping them from shooting them people's houses and beating up people. My fists got so sore I couldn't stick them in my pocket ... If you fight them with your fists, they had respect for you. But you didn't use blackjacks or guns on them. If you did they'd gang up on you and kill you."[8] According to deputy Bill White the fee basis for deputy pay continued for four more years. It was only the last four years he served that he was paid a salary.[8]

In early September the fall of the County political machine was followed by the resignation of Athens' Mayor, Paul Walker, and the town's four Aldermen. The resignations met with popular approval. The resignations came after a night time shot-gun blast through the front of Alderman Hugh Riggs's home.[25] Mayor Walker had previously refused a demand to resign made immediately after the gun-fight by the McMinn County American Legion and VFW posts.[26]

The "Battle of Athens" was followed by movements of veterans in other Tennessee counties promoting a statewide coalition against corrupt political machines in the upcoming November elections. Governor McCord countered an attempt to form a "Non-Partisan GI Political League" by directing the Young Democrats Clubs of Tennessee to recruit ex-GIs. There were strenuous efforts by the "Crump Organization," based in Shelby County, to counter the nascent GI organization.[27] A convention was held in Alamo, Tennessee, with the intention to establish a new national party. The convention was dissuaded by General Evans Carlson, USMC, who argued that the GIs should work through the existing political parties.[28]

The new GI government of Athens quickly encountered challenges including the re-emergence of old party loyalties.[29] On January 4, 1947, four of the five leaders of the GI Non-Partisan League declared in an open letter: "We abolished one machine only to replace it with another and more powerful one in the making."[30] The GI government in Athens eventually collapsed. Tennessee's GI political movement quickly faded and politics in the state returned to normal.[11][31] The Non-Partisan GI Political League replied to enquiries by veterans elsewhere in the United States with the advice that shooting it out was not the most desirable solution to political problems.[25]

Legacy

Joseph C. Goulden, in his history of immediate post-war America, The Best Years 1945-1950, discussed the Battle of Athens, how it sparked political ex-GI movements in three other Tennessee counties, as well as other boss-ruled Southern states, led to a convention with representatives from several Southern states, and how it raised fears that veterans would resort to further violence.[28] The Battle of Athens came in the mid-1940s, when there was much concern that returning GIs would be dangerously violent. Those concerns were addressed in an opinion piece by Warden Lawes, the author of Twenty Thousand Years at Sing Sing, in a New York Times opinion piece.[32] In a newspaper column, Eleanor Roosevelt had expressed a somewhat popular opinion that GIs should be checked for violent tendencies before they were demobilized. Bill White, the leader of Athens' "fighting band", came to see her point.[33] One of the reasons the GI League collapsed was the continuing GI related violence in McMinn County.[34][35] The Battle of Athens initially received criticism in the press. Coverage however quickly faded, and after Alan J. Gould, an executive with the Associated Press, told the Conference of State Directors of the Veterans Administration that the AP would try to suppress the use of the word "veteran" in conjunction with crime stories, the story of GI violence began to disappear.[36]

The 1992 made-for-television movie An American Story (produced by the Hallmark Hall of Fame) was loosely based upon the McMinn County War but set in a Texas town in 1945. It was nominated for two 1993 prime time Emmy Awards and one American Society of Cinematographers award.[37] The battle is also mentioned in the 1996 pro-gun rights novel Unintended Consequences and in the 2007 film Shooter. In 1996, C. Stephen Byrum, author of the history of McMinn County, published August 1, 1946. The Battle of Athens, Tennessee.

References

- ^ a b c Byrum, C. Stephen (1984). McMinn County. Memphis, Tennessee: Memphis State University Press. p. 115. ISBN 0-87870-176-1. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Lones Seiber (February–March 1985). "The Battle of Athens". American Heritage. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Byrum, C. Stephen (1984). McMinn County. Memphis, Tennessee: Memphis State University Press. p. 116. ISBN 0-87870-176-1. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ White, Bill (July 20, 2000). "An Interview with Bill White For the Veteran's Oral History Project Center for the Study of War and Society, Department of History, The University of Tennessee Knoxville" (PDF) (Interview). Interviewed by G. Kurt Piehler and Brandi Wilson. Athens, Tennessee. p. 25. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ White, Bill (July 20, 2000). "An Interview with Bill White For the Veteran's Oral History Project Center for the Study of War and Society, Department of History, The University of Tennessee Knoxville" (PDF) (Interview). Interviewed by G. Kurt Piehler and Brandi Wilson. Athens, Tennessee. p. 26. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ White, Bill (July 20, 2000). "An Interview with Bill White For the Veteran's Oral History Project Center for the Study of War and Society, Department of History, The University of Tennessee Knoxville" (PDF) (Interview). Interviewed by G. Kurt Piehler and Brandi Wilson. Athens, Tennessee. pp. 18–19. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ White, Bill (July 20, 2000). "An Interview with Bill White For the Veteran's Oral History Project Center for the Study of War and Society, Department of History, The University of Tennessee Knoxville" (PDF) (Interview). Interviewed by G. Kurt Piehler and Brandi Wilson. Athens, Tennessee. p. 24. Retrieved April 5, 2016.

- ^ a b c White, Bill (July 20, 2000). "An Interview with Bill White For the Veteran's Oral History Project Center for the Study of War and Society, Department of History, The University of Tennessee Knoxville" (PDF) (Interview). Interviewed by G. Kurt Piehler and Brandi Wilson. Athens, Tennessee. p. 24. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Byrum, C. Stephen (1984). McMinn County. Memphis, Tennessee: Memphis State University Press. p. 117. ISBN 0-87870-176-1. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ "Tennessee Veterans Are Wary Now" (PDF). The New York Times. August 18, 1946. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Egerton, John (1995). Speak Now Against the Day: the Generation Before the Civil Rights Movement in the South. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 393–396. ISBN 0-8078-4557-4.

- ^ a b White, Bill (July 20, 2000). "An Interview with Bill White For the Veteran's Oral History Project Center for the Study of War and Society, Department of History, The University of Tennessee Knoxville" (PDF) (Interview). Interviewed by G. Kurt Piehler and Brandi Wilson. Athens, Tennessee. p. 19. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ^ a b White, Bill (July 20, 2000). "An Interview with Bill White For the Veteran's Oral History Project Center for the Study of War and Society, Department of History, The University of Tennessee Knoxville" (PDF) (Interview). Interviewed by G. Kurt Piehler and Brandi Wilson. Athens, Tennessee. p. 20. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f White, Bill (July 20, 2000). "An Interview with Bill White For the Veteran's Oral History Project Center for the Study of War and Society, Department of History, The University of Tennessee Knoxville" (PDF) (Interview). Interviewed by G. Kurt Piehler and Brandi Wilson. Athens, Tennessee. p. 21. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Brooks, Jennifer E. (December 25, 2009). "Battle of Athens". The Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Byrum, C. Stephen (1984). McMinn County. Memphis, Tennessee: Memphis State University Press. p. 118. ISBN 0-87870-176-1. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Williams, Kate. "Riots in Tennessee". Tennessee State Library and Archives. Archived from the original on January 10, 2013. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

- ^ "Tennessee Sheriff Is Slain In Primary Day Violence" (PDF). The New York Times. August 2, 1946. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ^ a b c White, Bill (July 20, 2000). "An Interview with Bill White For the Veteran's Oral History Project Center for the Study of War and Society, Department of History, The University of Tennessee Knoxville" (PDF) (Interview). Interviewed by G. Kurt Piehler and Brandi Wilson. Athens, Tennessee. p. 22. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Armed Veterans Run Town After Tennessee Bloodshed" (PDF). The New York Times. August 2, 1946. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ^ a b "Election In Tennessee" (PDF). The New York Times. August 3, 1946. Retrieved April 5, 2016.

- ^ Byrum, C. Stephen (1984). McMinn County. Memphis, Tennessee: Memphis State University Press. p. 119. ISBN 0-87870-176-1. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Town's GI Leaders Take New Officers" (PDF). The New York Times. August 5, 1946. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ "Tennessee Sheriff is Slain in Primary Day Violence" (PDF). The New York Times. August 2, 1946. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ^ a b "(M)ayorless Athens Calm in Clean-Out" (PDF). The New York Times. September 8, 1946. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ "Mayor Resigns Post in Town Won by GIs" (PDF). The New York Times. September 7, 1946. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ "GI Movement Laps at Crump Province" (PDF). The New York Times. August 28, 1946. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ a b Goulden, Joseph C. (1976). The Best Years 1945–1950. New York: Antheneum. pp. 228. ISBN 0-689-10708-0.

- ^ "Elected GIs Doubt Course in Athens" (PDF). The New York Times. August 10, 1946. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ "Athens, Tenn., Regime Set Up by GIs Falls". The New York Times. January 12, 1947. Retrieved February 16, 2013.

- ^ "Tennesseans Act For 2-Party Rule" (PDF). The New York Times. August 1, 1947. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ "Will There Be A Crime Wave?" (PDF). The New York Times. November 5, 1944. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

- ^ White, Bill (July 20, 2000). "An Interview with Bill White For the Veteran's Oral History Project Center for the Study of War and Society, Department of History, The University of Tennessee Knoxville" (PDF) (Interview). Interviewed by G. Kurt Piehler and Brandi Wilson. Athens, Tennessee. p. 38. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ^ "Lesson From Tennessee" (PDF). The New York Times. January 16, 1947. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

- ^ White, Bill (July 20, 2000). "An Interview with Bill White For the Veteran's Oral History Project Center for the Study of War and Society, Department of History, The University of Tennessee Knoxville" (PDF) (Interview). Interviewed by G. Kurt Piehler and Brandi Wilson. Athens, Tennessee. pp. 23–24. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- ^ Goulden, Joseph C. (1976). The Best Years 1945–1950. New York: Antheneum. pp. 38. ISBN 0-689-10708-0.

- ^ "An American Story". Hallmark Hall of Fame Productions. IMDb. Retrieved January 8, 2013.