Furan

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Furan[1] | |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

1,4-Epoxybuta-1,3-diene 1-Oxacyclopenta-2,4-diene | |||

| Other names

Oxole

Oxa[5]annulene 1,4-Epoxy-1,3-butadiene 5-Oxacyclopenta-1,3-diene 5-Oxacyclo-1,3-pentadiene Furfuran Divinylene oxide | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.390 | ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C4H4O | |||

| Molar mass | 68.075 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless, volatile liquid | ||

| Density | 0.936 g/mL | ||

| Melting point | −85.6 °C (−122.1 °F; 187.6 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 31.3 °C (88.3 °F; 304.4 K) | ||

| -43.09·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| Hazards | |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | −69 °C (−92 °F; 204 K) | ||

| 390 °C (734 °F; 663 K) | |||

| Explosive limits | Lower: 2.3% Upper: 14.3% at 20 °C | ||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose)

|

> 2 g/kg (rat) | ||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | Pennakem | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related heterocycles

|

Pyrrole Thiophene | ||

Related compounds

|

Tetrahydrofuran (THF) 2,5-Dimethylfuran Benzofuran Dibenzofuran | ||

| Structure | |||

| C2v | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

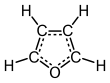

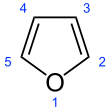

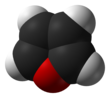

Furan is a heterocyclic organic compound, consisting of a five-membered aromatic ring with four carbon atoms and one oxygen. Chemical compounds containing such rings are also referred to as furans.

Furan is a colorless, flammable, highly volatile liquid with a boiling point close to room temperature. It is soluble in common organic solvents, including alcohol, ether, and acetone, and is slightly soluble in water.[2] Its odor is "strong, ethereal; chloroform-like".[3] It is toxic and may be carcinogenic in humans. Furan is used as a starting point to other speciality chemicals.[4]

History

The name "furan" comes from the Latin furfur, which means bran.[5] The first furan derivative to be described was 2-furoic acid, by Carl Wilhelm Scheele in 1780. Another important derivative, furfural, was reported by Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner in 1831 and characterised nine years later by John Stenhouse. Furan itself was first prepared by Heinrich Limpricht in 1870, although he called it "tetraphenol" (as if it were a four-carbon analog to phenol, C6H6O).[6][7]

Production

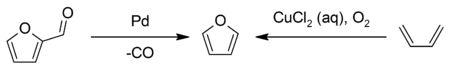

Industrially, furan is manufactured by the palladium-catalyzed decarbonylation of furfural, or by the copper-catalyzed oxidation of 1,3-butadiene:[4]

In the laboratory, furan can be obtained from furfural by oxidation to 2-furoic acid, followed by decarboxylation.[8] It can also be prepared directly by thermal decomposition of pentose-containing materials, and cellulosic solids, especially pine wood.

Synthesis of furans

The Feist–Benary synthesis is a classic way to synthesize furans, although many syntheses have been developed.[9] One of the simplest synthesis methods for furans is the reaction of 1,4-diketones with phosphorus pentoxide (P2O5) in the Paal–Knorr synthesis. The thiophene formation reaction of 1,4-diketones with Lawesson's reagent also forms furans as side products. Many routes exist for the synthesis of substituted furans.[10]

Chemistry

Furan is aromatic because one of the lone pairs of electrons on the oxygen atom is delocalized into the ring, creating a 4n + 2 aromatic system (see Hückel's rule) similar to benzene. Because of the aromaticity, the molecule is flat and lacks discrete double bonds. The other lone pair of electrons of the oxygen atom extends in the plane of the flat ring system. The sp2 hybridization is to allow one of the lone pairs of oxygen to reside in a p orbital and thus allow it to interact within the π system.

Due to its aromaticity, furan's behavior is quite dissimilar to that of the more typical heterocyclic ethers such as tetrahydrofuran.

- It is considerably more reactive than benzene in electrophilic substitution reactions, due to the electron-donating effects of the oxygen heteroatom. Examination of the resonance contributors shows the increased electron density of the ring, leading to increased rates of electrophilic substitution.[11]

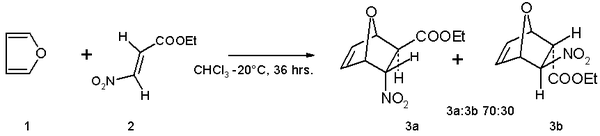

- Furan serves as a diene in Diels–Alder reactions with electron-deficient dienophiles such as ethyl (E)-3-nitroacrylate.[12] The reaction product is a mixture of isomers with preference for the endo isomer:

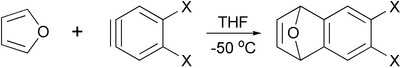

- Diels-Alder reaction of furan with arynes provides corresponding derivatives of dihydronaphthalenes, which are useful intermediates in synthesis of other polycyclic aromatic compounds.[13]

- Hydrogenation of furans sequentially affords dihydrofurans and tetrahydrofurans.

- In the Achmatowicz reaction, furans are converted to dihydropyran compounds.

- Pyrrole can be prepared industrially by reacting furan and ammonia in the presence of solid acid catalysts, such as SiO2 and Al2O3.[14]

Safety

Furan is found in heat-treated commercial foods and is produced through thermal degradation of natural food constituents.[15][16] It can be found in roasted coffee, instant coffee, and processed baby foods.[16][17][18] Research has indicated that coffee made in espresso makers, and, above all, coffee made from capsules, contains more furan than that made in traditional drip coffee makers, although the levels are still within safe health limits.[19]

Exposure to furan at doses about 2000 times the projected level of human exposure from foods increases the risk of hepatocellular tumors in rats and mice and bile duct tumors in rats.[20] Furan is therefore listed as a possible human carcinogen.[20]

See also

- BS 4994 – Furan resin as thermoset FRP for chemical process plant equipments

- Furanocoumarin

- Furanoflavonoid

- Furanose

- Furantetracarboxylic acid

- Simple aromatic rings

- Furan fatty acids

- Tetrahydrofuran

References

- ^ Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 392. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- ^ Jakubke, Hans Dieter; Jeschkeit, Hans (1994). Concise Encyclopedia of Chemistry. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 1–1201. ISBN 0-89925-457-8.

- ^ DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2016–171, p. 2, Accessed Nov 2019

- ^ a b Hoydonckx, H. E.; Van Rhijn, W. M.; Van Rhijn, W.; De Vos, D. E.; Jacobs, P. A. "Furfural and Derivatives". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a12_119.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Senning, Alexander (2006). Elsevier's Dictionary of Chemoetymology. Elsevier. ISBN 0-444-52239-5.

- ^ Limpricht, H. (1870). "Ueber das Tetraphenol C4H4O". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 3 (1): 90–91. doi:10.1002/cber.18700030129.

- ^ Rodd, Ernest Harry (1971). Chemistry of Carbon Compounds: A Modern Comprehensive Treatise. Elsevier.

- ^ Wilson, W. C. (1941). "Furan". Organic Syntheses; Collected Volumes, vol. 1, p. 274.

- ^ Hou, X. L.; Cheung, H. Y.; Hon, T. Y.; Kwan, P. L.; Lo, T. H.; Tong, S. Y.; Wong, H. N. (1998). "Regioselective syntheses of substituted furans". Tetrahedron. 54 (10): 1955–2020. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(97)10303-9.

- ^ Katritzky, Alan R. (2003). "Synthesis of 2,4-disubstituted furans and 4,6-diaryl-substituted 2,3-benzo-1,3a,6a-triazapentalenes" (PDF). Arkivoc. 2004 (2): 109. doi:10.3998/ark.5550190.0005.208.

- ^ Bruice, Paula Y. (2007). Organic Chemistry (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-196316-0.

- ^ Masesane, I.; Batsanov, A.; Howard, J.; Modal, R.; Steel, P. (2006). "The oxanorbornene approach to 3-hydroxy, 3,4-dihydroxy and 3,4,5-trihydroxy derivatives of 2-aminocyclohexanecarboxylic acid". Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2 (9): 9. doi:10.1186/1860-5397-2-9. PMC 1524792. PMID 16674802.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Filatov, M. A.; Baluschev, S.; Ilieva, I. Z.; Enkelmann, V.; Miteva, T.; Landfester, K.; Aleshchenkov, S. E.; Cheprakov, A. V. (2012). "Tetraaryltetraanthra[2,3]porphyrins: Synthesis, Structure, and Optical Properties" (PDF). J. Org. Chem. 77 (24): 11119–11131. doi:10.1021/jo302135q. PMID 23205621.

- ^ Harreus, Albrecht Ludwig. "Pyrrole". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a22_453. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Anese, M.; Manzocco, L.; Calligaris, S.; Nicoli, M. C. (2013). "Industrially Applicable Strategies for Mitigating Acrylamide, Furan and 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural in Food" (PDF). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 61 (43): 10209–14. doi:10.1021/jf305085r. PMID 23627283.

- ^ a b Moro, S.; Chipman, J. K.; Wegener, J. W.; Hamberger, C.; Dekant, W.; Mally, A. (2012). "Furan in heat-treated foods: Formation, exposure, toxicity, and aspects of risk assessment" (PDF). Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 56 (8): 1197–1211. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201200093. hdl:1871/41889. PMID 22641279.

- ^ European Food Safety Authority (2011). "Update on furan levels in food from monitoring years 2004–2010 and exposure assessment". EFSA Journal. 9 (9): 2347. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2347.

- ^ Waizenegger, J.; Winkler, G.; Kuballa, T.; Ruge, W.; Kersting, M.; Alexy, U.; Lachenmeier, D. W. (2012). "Analysis and risk assessment of furan in coffee products targeted to adolescents". Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A. 29 (1): 19–28. doi:10.1080/19440049.2011.617012. PMID 22035212.

- ^ "Espresso makers: Coffee in capsules contains more furan than the rest". Science Daily. April 14, 2011.

- ^ a b Bakhiya, N.; Appel, K. E. (2010). "Toxicity and carcinogenicity of furan in human diet" (PDF). Archives of Toxicology. 84 (7): 563–578. doi:10.1007/s00204-010-0531-y. PMID 20237914.