Hyksos

It has been suggested that Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since June 2020. |

| Periods and dynasties of ancient Egypt |

|---|

|

All years are BC |

The Hyksos (/ˈhɪksɒs/; Egyptian ḥqꜣ(w)-ḫꜣswt, Egyptological pronunciation: hekau khasut,[1] "ruler(s) of foreign lands"; Ancient Greek: Ὑκσώς, Ὑξώς) were Egyptian rulers of Levantine origins[2] who established the Fifteenth Dynasty of Egypt based at the city of Avaris in the Nile delta. From there they ruled the northern part of the country during the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1800-1550 BC). While the Hellenistic Egyptian historian Manetho portrayed the Hyksos as invaders and oppressors, modern Egyptology no longer believes that the Hyksos conquered Egypt in an invasion.[3] Instead, Hyksos rule had been preceded by groups of Canaanite peoples settled in the eastern delta who likely seceded from central Egyptian control near the end of the Thirteenth Dynasty.[4]

Many details about Hyksos rule, such as the true extent of their kingdom and even the names and order of their kings, remain uncertain. The Hyksos had many Levantine or Canaanite customs, but show many Egyptian cultural features as well.[5] They have been credited with introducing several technological innovations to Egypt, including the horse and chariot, as well as the sickle sword and composite bow, however this remains disputed.[6]

The Hyksos did not control all of Egypt, coexisting with Sixteenth and Seventeenth Dynasties, based in Thebes.[7] They were eventually conquered by Ahmose I, who founded the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Ahmose's conquest was preceeded by warfare between the Hyksos and Ahmose's predecessors Seqenenra Taa and Kamose of the Seventeenth Dynasty. Sources for the war are poor and are written from the Theban perspective.[8] Egyptians in the following centuries would use the Hyksos as examples of particularly blood-thirsty and oppressive foreign rulers.

Name

| Hyksos in hieroglyphs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

ḥḳꜣ-ḫꜣsw / ḥḳꜣw-ḫꜣswt[9][10], hekau khasut,[1] Ruler(s) of the foreign countries[9] | ||||||||

| Greek | Hyksos (Ὑκσώς), Hykussos (Ὑκουσσώς)[11] | |||||||

The term "Hyksos" derives, via the Greek Ὑκσώς (Hyksôs), from the Egyptian expression ḥḳꜣ-ḫꜣswt or ḥḳꜣw-ḫꜣswt, meaning "rulers [of] foreign lands".[9][10] The Greek form is likely a textual corruption of an earlier Ὑκουσσώς (Hykoussôς).[11] Properly speaking, the term Hyksos refers to the rulers of the dynasty rather than to a people, but was already used by the first-century CE Jewish historian Josephus as an ethnic term.[12]

The Egyptian term ḥḳꜣ-ḫꜣswt was used to refer to various Nubian and Levantine rulers.[13] Based on the use of the name in a Hyksos inscription from Avaris, the name was used by the Hyksos as a title for themselves.[14] Scarabs also attest the use of this title for pharaohs usually assigned to the Fourteenth or Sixteenth Dynasty of Egypt, who are sometimes called "'lesser' Hyksos."[15] All other texts in the Ancient Egyptian language except the Turin King List do not call the Hyksos by this name, instead referring to them as Asiatics (ꜥꜣmw).[16]

Josephus gives the name as meaning "shepherd kings" or "captive kings" in his Against Apion, where he describes the Hyksos as they appeared in the Hellenistic Egyptian historian Manetho.[17] Josephus's rendition may arise from a later Egyptian pronunciation of ḥḳꜣ-ḫꜣswt as ḥḳꜣ-šꜣsw, which was then understood to mean "lord of shepherds."[18] It is unclear if this translation was found in Manetho; an Armenian translation of an epitome of Manetho given by the late antique historian Eusebius gives the correct translation of "foreign kings".[19]

Origins

Ancient historians

In his epitome of Manetho, Josephus connected the Hyksos with the Jews,[20] but he also called them Arabs. In their own epitomes of Manetho, the Late antique historians Sextus Julius Africanus and Eusebius say that the Hyksos came from Phoenicia.[17] Until the excavation and discovery of Tell El-Dab'a (the site of the Hyksos capital Avaris) in 1966, historians relied on these accounts for the Hyksos period.[21][2]

Modern historians

Material finds at Tell El-Dab'a indicate that the Hyksos originated in either the northern or southern Levant.[2] The Hyksos' personal names indicate that they spoke a Western Semitic language and "may be called for convenience sake Canaanites."[22] Kamose, the last king of the Theban 17th Dynasty, refers to Apepi as a "Chieftain of Retjenu" in a stela that implies a Levantine background for this Hyksos king.[23] According to Anna-Latifa Mourad, the Egyptian application of the term ꜥꜣmw to the Hyksos could indicate a range of backgrounds, including newly arrived Levantines or people of mixd Levantine-Egyptian origin.[24] Earlier arguments that the Hyksos names might be Hurrian have been rejected,[25] while early-twentieth-century proposals that the Hyksos were Indo-Europeans "fitted European dreams of Indo-European supremacy, now discredited."[26]

History

Background and arrival in Egypt

The only ancient account of the whole Hyksos period is by the Hellenistic Egyptian historian Manetho, who, whoever, exists only as quoted by others.[27] As recorded by Josephus, Manetho describes the beginning of Hyksos rule thusly:

A people of ignoble origin from the east, whose coming was unforeseen, had the audacity to invade the country, which they mastered by main force without difficulty or even battle. Having overpowered the chiefs, they then savagely burnt the cities, razed the temples of the gods to the ground, and treated the whole native population with the utmost cruelty, massacring some, and carrying off the wives and children of others into slavery.[28]

Manetho's invasion narrative is "nowadays rejected by most scholars."[3] Instead, it appears that the establishment of Hyksos rule was mostly peaceful and did not involve an invasion of an entirely foreign population.[29] Archaeology shows a continuous Asiatic presence at Avaris for over 150 years before the beginning of Hyksos rule,[30] with gradual Canaanite settlement beginning there c. 1800 BC during the Twelfth Dynasty.[10] Manfred Bietak argues that Hyksos "should be understood within a repetitive pattern of the attraction of Egypt for western Asiatic population groups that came in search of a living in the country, especially the Delta, since prehistoric times."[31]

The final powerful pharaoh of the Egyptian Thirteenth dynasty was Sobekhotep IV, who died around 1725 BC, after which Egypt appears to have splintered into various kingdoms, including one based at Avaris ruled by the Fourteenth dynasty.[4] This dynasty would be replaced by the Hyksos Fifteenth Dynasty and would establish "loose control over northern Egypt by intimidation or force,"[32] thus greatly expanding the area under Avaris's control.[33] Kim Ryholt argues that the Fifteenth Dynasty invaded and displayed the Fourteenth, however Alexander Ilin-Tomich argues that this is "not sufficiently substantiated."[25]

Rule

The length of time the Hyksos ruled is unclear. The fragmentary Turin King List says that there were six Hyksos kings who collectively ruled 108 years,[34] however in 2018 Kim Ryholt proposed a new reading of as many as 149 years, while Thomas Schneider proposed a length between 160-180 years.[35]

The area under directed control of the Hyksos was probably limited to the eastern Nile delta.[7] The Hyksos claimed to be rulers of both Lower and Upper Egypt; however, their southern border was marked at Hermopolis and Cusae.[5] Some objects might suggest a Hyksos presence in Upper Egypt, however they may have been Theban war booty or attest simply to short term raids, trade, or diplomatic contact.[36] Although the royal seat was in Avaris, Memphis was probably also an important administrative center.[37] However, the nature of Hyksos control over the region of Thebes and Memphis remains unclear.[7] Most likely Hyksos rule covered the area from Middle Egypt to southern Palestine[38] Older scholarship believed, due to the distribution of Hyksos goods with the names of Hyksos rulers in places such as Baghdad and Knossos, that Hyksos had ruled a vast empire, however it seems more likely to have been the result of diplomatic gift exchange and far-flung trade networks.[39][7]

The rule of the Hyksos overlaps with that of the native Egyptian pharaohs of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Dynasties, better known as the Second Intermediate Period. The Theban rulers of the Seventeenth Dynasty are known to have imitated the Hyksos both in their architecture and regnal names.[40] There is evidence of friendly relations between the Hyksos and Thebes, including possibly a marriage alliance, prior to the reign of the Theban pharaoh Seqenenra Taa.[41]

Wars with the Seventeenth Dynasty

The conflict between Thebes and the Hyksos is known exclusively from pro-Theban sources, and it is difficult to construct a chronology.[8] These sources propagandistically portray the conflict as a war of national liberation. This perspective was formerly taken by scholars as well but is no longer thought to be accurate.[42][43]

Hostilities between the Hyksos and the Theban Seventeenth Dynasty appear to have begun during the reign of Theban king Seqenenra Taa. Seqenenra Taa's mummy shows that he was killed by several blows of an axe to the head, apparently in battle with the Hyksos.[44] It is unclear why hostilities may have started, but the much later fragmentary New Kingdom tale The Quarrel of Seqenenra Taa and Apepi blames the Hyksos ruler Apepi/Apophis for initiating the conflict by demanding that Seqenenra Taa remove a pool of hippopotamuses near Thebes.[41] However, this is a satire on an Egyptian story-telling genre of the "king's novel" rather than a historical text.[44]

Three years later, Seqenenra Taa's successor Kamose initiated a campaign against several cities loyal to the Hyksos, the account of which he had preserved on the Carnarvon Tablet.[45] The text includes a complaint by Kamose about the divided and occupied state of Egypt:

To what effect do I perceive it, my might, while a ruler is in Avaris and another in Kush, I sitting joined with an Asiatic and a Nubian, each man having his (own) portion of this Egypt, sharing the land with me. There is no passing him as far as Memphis, the water of Egypt. He has possession of Hermopolis, and no man can rest, being deprived by the levies of the Setiu. I shall engage in battle with him and I shall slit his body, for my intention is to save Egypt, striking the Asiatics.[46]

Following a common literary device, Kamose's advisors are portrayed as trying to dissuade the king, but the king attacks anyway.[45] He recounts his destruction of the city of Nefrusy as well as several other cities loyal to the Hyksos.[44] On a second stele, Kamose claims to have captured Avaris, but returned to Thebes after capturing a messenger between Apepi and the king of Kush.[44]

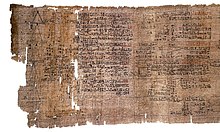

Ahmose I continued the war against the Hyksos, most likely conquering Memphis, Tjaru and Heliopolis early in his reign, the latter two of which are mentioned in an entry of the Rhind mathematical papyrus.[44] Knowledge of Ahmose I's campaigns against the Hyksos mostly comes from the tomb of Ahmose, son of Ebana, who claims that Ahmose I sacked Avaris.[47] Thomas Schneider places the conquest in year 18 of Ahmose's reign.[48] However, excavations of Tell El-Dab'a (Avaris) show no widespread destruction of the city, which instead seems to have been abandoned by the Hyksos.[44] Manetho, as recorded in Josephus, states that the Hyksos were allowed to leave after concluding a treaty.[49] Although Manetho indicates that the Hyksos population was expelled to the Levant, there is no archaeological evidence for this, and Manfred Bietak argues on the basis of archaeological finds throughout Egypt that it is likely that numerous Asiatics were resettled in other locations in Egypt as artisans and craftsmen.[50]

Rulers

The names, the order, length of rule, and even the total number of the Fifteenth Dynasty rulers are not known with full certainty. After the end of their rule, the Hyksos kings were not considered to have been legitimate rulers of Egypt and were therefore omitted from most king lists.[51] The fragmentary Turin King List included six Hyksos kings, however only the name of the last, Khamudi, is preserved.[52] Ryholt associates three other rulers known from inscriptions with the dynasty, Khyan, Sakir-Har, and Apepi.[53] The name of Khyan's son, Yanassi, is also preserved from Tell El-Dab'a.[33]

Some kings are attested from either fragments of the Turin King List or from other sources who may have been Hyksos rulers. According to Ryholt, kings Semqen and Aperanat, known from the Turin King List, may have been early Hyksos rulers,[54] however Jürgen von Beckerath assigns these kings to the Sixteenth Dynasty of Egypt.[55] Another king known from scarabs, Sheshi,[56] is believed by "many [...] scholars" to be a Hyksos king,[57] however Ryholt assigns this king to the Fourteenth Dynasty of Egypt.[58]

Josephus's epitome of Manetho lists the rulers of the fifteenth dynasty as Salatis, Bnon, Apachnas, Apophis, Jannas, and Assis.[59] It is difficult to reconcile the Turin King List and other sources with names known from Manetho via Josephus.[56] The name Apepi/Apophis appears on both lists, however.[60] Bietak identifies Sakir-Har with Salitis,[61] while Assis may be Yanassi,[33] although it is also possible that he is Jannas.[62] Thomas Schneider instead proposes that Khyan is identical with Apachnas and Sakir-Har with Assis.[63] Schneider's proposed identifications, with reconstructed Semitic names for the pharaohs, is found in the table below:[63][64]

| Name in Manetho | Name in other sources | Reconstructed Semitic name |

|---|---|---|

| Salitis | ? | Šarā-Dagan (Šȝrk[n]) |

| Bnon | ? | *Bin-ʿAnu |

| Apachnan | Khyan | (ʿApaq-)Hajran |

| Iannas | Yanassi | Jinaśśi’-Ad |

| Archles/Assis | Sakir-Har | Sikru-Haddu |

| Apophis | Apepi | Apapi |

| - | Khamudi | Halmu’di |

None of the proposed identifications besides of Apepi and Apophis is considered certain.[65]

The two best attested kings are Khyan and Apepi,[66] the latter of whom is attested as a contemporary of seventeenth-dynasty pharaohs Kamose and Ahmose I.[67] The only kings for whom their order is certain are Khyan and his son Yanassi.[68] Ryholt, however, has proposed that Yanassi may not have ruled in his own right.[69] Ryholt proposes a dynastic order of for the final three pharaohs of the fifteenth dynasty as: Khyan (10 years), Apophis (40 years), and then Khamudi (less than ten years).[70] However, on the basis of the Rhind mathematical papyrus, Schneider argues that Khamudi must have reigned at least 11 years,[48] and David Aston finds Ryholt's suggestion that Khyan immediately preceded Apepi unlikely.[63] Schneider agrees that Sakir-Har may be the first of the dynasty, although he does not identify him with Salitis.[64]

In Sextus Julius Africanus's epitome of Manetho, the rulers of Sixteenth Dynasty are also identified as "shepherds" (i.e. Hyksos) rulers.[71] Following the work of Ryholt in 1997, most but not all scholars now identify the sixteenth dynasty as a native Egyptian dynasty based in Thebes, following Eusebius's epitome of Manetho; this dynasty would be contemporary to the Hyksos.[72]

Culture and technology

The Hyksos show a mix of Egyptian and Syro-Palestinian cultural traits.[5] The Hyksos do not appear to have produced any court art,[73] instead appropriating monuments from earlier dynasties by writing their names on them. Many of these are inscribed with the name of King Khyan.[74] There are also no surviving Hyksos funeral monuments at Memphis in the Egyptian style, though these may have been destroyed.[75] King Apepi is known to have patronized Egyptian scribal culture, commissioning the copying of the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus.[76]

The Hyksos are known to have worshiped the Canaanite storm god Baal-zephon, who was associated with the Egyptian god Set.[77] Set appears to have been the patron god of Avaris as early as the Fourteenth dynasty.[78] Hyksos iconography of their kings on some scarabs shows a mixture of Egyptian pharaonic dress with a raised club, the iconography of Baal-zephon.[79] Despite later sources claiming the Hyksos were opposed to the worship of other gods, votive objects given by Hyksos rulers to gods such as Ra, Hathor, Sobek, and Wadjet have also survived.[80]

Further ethnic markers of the Hyksos in the archaeological record include burying their dead within settlements rather than outside them like the Egyptians.[81] The Hyksos also practiced the burial of horses and other equids, likely a composite custom of the Egyptian association of the god Seth with the donkey and near-eastern notions of equids as representing status.[82] The horse burials suggest that the Hyksos introduced both the horse and the chariot to Egypt,[83] however no archaeological, pictorial, or textual evidence exists that the Hyksos possessed chariots, which are first mentioned as ridden by the Egyptians in warfare against them by Ahmose, son of Ebana at the close of Hyksos rule.[84] Josef Wegner further argues that horse-riding may have been present in Egypt as early as the late Middle Kingdom, prior to the adoption of chariot technology.[85] Traditionally, the Hyksos have also been credited with introducing a number of other military innovations, such as the sickle-sword and composite bow; however, "[t]o what extent the kingdom of Avaris should be credited for these innovations is debatable," with scholarly opinion currently divided.[6] It is also possible that the Hyksos introduced more advanced bronze working and weaving techniques, though this is inconclusive.[86] They may have worn full-body armor, and introduced new musical instruments to Egypt as well.[86]

Legacy

The Hyksos' rule continued to be condemned by New Kingdom pharaohs such as Hatshepsut, who, 80 years after their defeat, claimed to rebuild many shrines and temples they had neglected.[73] The nineteenth-dynasty story Quarrel of Apepi and Seqenenra Taa claimed that the Hyksos worshiped no god but Set, making the conflict into one between Ra, the patron of Thebes, and Set as patron of Avaris.[87] Furthermore, the battle with the Hyksos was interpreted in light of the mythical battle between the gods Horus and Set, transforming Set into an Asiatic deity while also allowing for the integration of Asiatics into Egyptian society.[88]

Manetho's portrayal of the Hyksos, written nearly 1300 years after the end of Hyksos rule and found in Josephus, is even more negative than the New Kingdom sources.[73] This account portrayed the Hyksos "as violent conquerors and oppressors of Egypt" has been highly influential for perceptions of the Hyksos until modern times.[89] Marc van de Mieroop argues that Josephus's portrayal of the initial Hyksos invasion is no more trustworthy than his later claims that they were related to the Exodus, supposedly portrayed in Manetho as performed by a band of lepers.[90] The Hyksos supposed connections to the Exodus have continued to inspire interest in them.[26]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Bourriau 2000, p. 174.

- ^ a b c Mourad 2015, p. 10.

- ^ a b Ilin-Tomich 2016, p. 5.

- ^ a b Bourriau 2000, pp. 177–178.

- ^ a b c Bourriau 2000, p. 182.

- ^ a b Ilin-Tomich 2016, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d Ilin-Tomich 2016, p. 7.

- ^ a b Morenz & Popko 2010, pp. 108–109.

- ^ a b c Flammini 2015, p. 240.

- ^ a b c Ben-Tor 2007, p. 1.

- ^ a b Schneider 2008, p. 305.

- ^ Bietak 2010, p. 139.

- ^ Candelora 2017, pp. 208=209.

- ^ Candelora 2017, p. 204.

- ^ Müller 2018, p. 211.

- ^ Candelora 2017, pp. 206–208.

- ^ a b Mourad 2015, p. 9.

- ^ Morenz & Popko 2010, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Verbrugghe & Wickersham 1996, p. 99.

- ^ Assmann.

- ^ Flammini 2015, p. 236.

- ^ Bietak 2016, pp. 267–268.

- ^ Ryholt 1997, p. 128.

- ^ Mourad 2015, p. 216.

- ^ a b Ilin-Tomich 2016, p. 6.

- ^ a b Van de Mieroop 2011, p. 166.

- ^ Raspe 1998, p. 126-128.

- ^ Josephus 1926, p. 196.

- ^ Mourad 2015, p. 130.

- ^ Bietak 2006, p. 285.

- ^ Biatek 2006, p. 285.

- ^ Bietak 1999, p. 377.

- ^ a b c Bourriau 2000, p. 180.

- ^ Ryholt 1997, p. 186.

- ^ Aston 2018, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Popko 2013, p. 3.

- ^ Bourriau 2000, p. 183.

- ^ Popko 2013, p. 2.

- ^ Morenz & Popko 2010, p. 105.

- ^ Morenz & Popko 2010, p. 108.

- ^ a b Van de Mieroop 2011, p. 160.

- ^ Morenz & Popko 2010, p. 109.

- ^ Popko 2013, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b c d e f Popko 2013, p. 4.

- ^ a b Van de Mieroop 2011, p. 161.

- ^ Simpson 2003, p. 346.

- ^ Van de Mieroop 2011, p. 177.

- ^ a b Schneider 2006, p. 195.

- ^ Bourriau 2003, pp. 201–202.

- ^ Bietak 2010, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Ben-Tor 2007, p. 2.

- ^ Ryholt 1997, p. 118.

- ^ Ryholt 1997, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Ryholt 1997, pp. 121–122.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 120–121.

- ^ a b Bietak 1999, p. 378.

- ^ Müller 2018, p. 210.

- ^ Ryholt 1997, p. 409.

- ^ Josephus 1926, pp. 192–195.

- ^ Ilin-Tomich 2016, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Bourriau 2000, p. 179.

- ^ Ryholt 1997, pp. 120–121.

- ^ a b c Aston 2018, p. 17.

- ^ a b Schneider 2006, p. 194.

- ^ Ilin-Tomich 2016, p. 11.

- ^ Aston 2018, p. 18.

- ^ Aston 2018, p. 16.

- ^ Aston 2018, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Ryholt 1997, p. 256.

- ^ Ryholt 1997, pp. 119, 188.

- ^ Bourriau 2003, p. 179.

- ^ Ilin-Tomich 2016, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Bietak 1999, p. 379.

- ^ Müller 2018, p. 212.

- ^ Bouriau 2000, p. 183.

- ^ van de Mieroop 2011, pp. 151–153.

- ^ Bietak 1999, pp. 377–378.

- ^ Bourriau 2000, p. 177.

- ^ Morenz & Popko 2010, p. 104.

- ^ Ryholt 1997, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Bietak 2016, p. 268.

- ^ Mourad 2015, p. 15.

- ^ Hernandez 2014, p. 112.

- ^ Herslund 2018, p. 151.

- ^ Wegner 2015, p. 76.

- ^ a b Van de Mieroop 2011, p. 149.

- ^ Van de Mieroop 2011, p. 163.

- ^ Assmann 2003, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Van de Mieroop 2011, p. 164.

- ^ Van de Mieroop 2011, pp. 164–165.

References

- Aston, David A. (2018). "How Early (and How Late) Can Khyan Really Be: An Essay Based on ›Conventional Archaeological Methods‹". In Forstner-Müller, Irene; Moeller, Nadine (eds.). THE HYKSOS RULER KHYAN AND THE EARLY SECOND INTERMEDIATE PERIOD IN EGYPT: PROBLEMS AND PRIORITIES OF CURRENT RESEARCH. Proceedings of the Workshop of the Austrian Archaeological Institute and the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, Vienna, July 4 – 5, 2014. Holzhausen. pp. 15–56. ISBN 978-3-902976-83-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Assmann, Jan (2003). The mind of Egypt: history and meaning in the time of the Pharaohs. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674012110.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - von Beckerath, Jürgen (1999). Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen. von Zabern. ISBN 3-8053-2591-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ben-Tor, Daphne (2007). Scarabs, Chronology, and Connections: Egypt and Palestine in the Second Intermediate Period (PDF). Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bietak, Manfred (2016). "The Egyptian community in Avaris during the Hyksos period". Ägypten und Levante / Egypt and the Levant. 26: 263–274. JSTOR 44243953.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bietak, Manfred (2010). "FROM WHERE CAME THE HYKSOS AND WHERE DID THEY GO?". In Maréee, Marcel (ed.). THE SECOND INTERMEDIATE PERIOD (THIRTEENTH–SEVENTEENTH DYNASTIES): Current Research, Future Prospects. Peeters. pp. 139–181.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bietak, Manfred (2006). "The predecessors of the Hyksos". In Gitin, Seymour; Wright, Edward J.; Dessel, J. P. (eds.). Confronting the Past: Archaeological and Historical Essays on Ancient Israel in Honor of William G. Dever. Eisenbrauns.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bietak, Manfred (1999). "Hyksos". In Bard, Kathryn A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge. pp. 377–379.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bourriau, Janine (2000). "The Second Intermediate Period (c. 1650-1550 BC)". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Candelora, Danielle (2017). "Defining the Hyksos: A Reevaluation of the Title HqA xAswtand Its Implications for Hyksos Identity". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 53: 203–221.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Flammini, Roxana (2015). "BUILDING THE HYKSOS' VASSALS: SOME THOUGHTS ON THE DEFINITION OF THE HYKSOS SUBORDINATION PRACTICES". Ägypten und Levante / Egypt and the Levant. 25: 233–245. JSTOR 43795213.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ilin-Tomich, Alexander (2016). "Second Intermediate Period". In Wendrich, Willeke; et al. (eds.). UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Josephus, Flavius (1926). Josephus in Eight Volumes, 1: The Life; Against Apion. Translated by Thackeray, H. St. J.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hernández, Roberto A. Díaz (2014). "The Role of the War Chariot in the Formation of the Egyptian Empire in the Early 18th Dynasty". Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur. 43: 109–122. JSTOR 44160271.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Herslund, Ole (2018). "Chronicling Chariots: Texts, Writing and Language of New Kingdom Egypt". In Veldmeijer, André J; Ikram, Salima (eds.). Chariots in Ancient Egypt : The Tano Chariot, A Case Study. Sidestone Press. ISBN 9789088904684.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Morenz, Ludwig D.; Popko, Lutz (2010). "The second intermediate period and the new kingdom". In Lloyd, Alan B. (ed.). A Companion to Ancient Egypt. Vol. 1. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 101–119.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mourad, Anna-Latifa (2015). Rise of the Hyksos Egypt and the Levant from the Middle Kingdom to the early Second Intermediate Period. Oxford Archaeopress. doi:10.2307/j.ctvr43jbk. JSTOR j.ctvr43jbk.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Müller, Vera (2018). "Chronological Concepts for the Second Intermediate Period and Their Implications for the Evaluation of Its Material Culture". In Forstner-Müller, Irene; Moeller, Nadine (eds.). THE HYKSOS RULER KHYAN AND THE EARLY SECOND INTERMEDIATE PERIOD IN EGYPT: PROBLEMS AND PRIORITIES OF CURRENT RESEARCH. Proceedings of the Workshop of the Austrian Archaeological Institute and the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, Vienna, July 4 – 5, 2014. Holzhausen. pp. 199–216. ISBN 978-3-902976-83-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Popko, Lutz (2013). "Late Second Intermediate Period". In Wendrich, Willeke; et al. (eds.). UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Raspe, Lucia (1998). "Manetho on the Exodus: A Reappraisal". Jewish Studies Quarterly. 5 (2): 124–155. JSTOR 40753208.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ryholt, Kim (1997). The Political Situation in Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period c.1800-1550 B.C. Museum Tuscalanum Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schneider, Thomas (2006). "The Relative Chronology of the Middle Kingdom and the Hyksos Period". In Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David A. (eds.). Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Brill. pp. 168–196. ISBN 9004113851.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schneider, Thomas (2008). "DAS ENDE DER KURZEN CHRONOLOGIE: EINE KRITISCHE BILANZ DER DEBATTE ZUR ABSOLUTEN DATIERUNG DES MITTLEREN REICHES UND DER ZWEITEN ZWISCHENZEIT". Ägypten und Levante / Egypt and the Levant. 18: 275–313. JSTOR 23788616.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Simpson, William Kelly; et al., eds. (2003). The Literature of Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, and Poetry. Yale University Press. JSTOR j.ctt5vm2m5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Van de Mieroop, Marc (2011). A History of Ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781405160704.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Verbrugghe, Gerald P.; Wickersham, John M. (1996). Berossos and Manetho, introduced and translated: native traditions in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472107224.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wegner, Josef (2015). "A ROYAL NECROPOLIS AT SOUTH ABYDOS: New Light on Egypt's Second Intermediate Period". Near Eastern Archaeology. 78 (2): 68–78. JSTOR 10.5615/neareastarch.78.2.0068.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)