Law of Nazi Germany

From 1933 to 1945, the Nazi regime ruled Germany and controlled much of Europe. During this time, Nazi Germany shifted from the post-World War I society which characterized the Weimar Republic and introduced an ideology of "biological racism" into the country's legal and justicial systems.[1] The shift from the traditional legal system (the "normative state") to the Nazis' ideological mission (the "prerogative state")[1] enabled all of the subsequent acts of the Hitler regime, including its atrocities) to be performed "legally". For this to succeed, the normative judicial system needed to be reworked; judges, lawyers and other civil servants acclimatized themselves to the new Nazi laws and personnel.

History

After World War I, Germany considered the law a "most respected entity"[2] as the country regained stability and public confidence. Many German lawyers and judges were Jewish.[2] Adolf Hitler was inspired by Benito Mussolini's October 1922 March on Rome, which brought Mussolini's National Fascist Party to power in Italy.[2]

Hitler's Beer Hall Putsch took place in Munich, Bavaria, on 8–9 November 1923. The attempted coup was halted by Bavarian police; 16 Nazis were killed, and Hitler was imprisoned (where he wrote Mein Kampf).[2] Hitler exploited Weimar's economic hardships, which included hyperinflation and the effects of the Great Depression.[2] His actions and goals have been described as using the "constitution to destroy the constitution" and the "rules of the republic to destroy the republic".[2]

Nazi influence increased after the party became the largest in the Reichstag. Increasing public pressure, including marches, lawlessness and racism, forced president Paul von Hindenburg to appoint Hitler Chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933; this was known as the Machtergreifung.[3]

The 27 February 1933 Reichstag fire was used as a pretext to suspend the Weimar Constitution and impose a four-year state of emergency. The Reichstag Fire Decree would "safeguard public security"[4] by restricting civil liberties and granting increased power to the police, and the SA arrested 4,000 members of the Communist Party.[5] Legislative power was given to Hitler so his government could create laws without Rechstag consent.[6]

Several principles were invoked during the state of emergency. The Führerprinzip ("leader principle") designated Hitler as above the law.[4] The Volkist Principle of Racial Inequality organised the judiciary by race; anyone not considered part of the Volksgemeinschaft (people's community) was seen as undeserving of legal protection.[4]

In 1933, The Reich Ministry of the Interior (RMI) was utilised by the Nazi government to consolidate Hitler's rise to power. New civil-service legislation enabled the removal of non-Aryans and the "politically unreliable."[1] Autonomy was removed from individual German states and provinces through a process of coordination (Gleichschaltung), and Nazi ideology was imposed by racial and ancestral legislation which defined who was (or was not) a German.[1] In 1936, SS leader and RMI state secretary Heinrich Himmler was placed in charge of the civil police. With the growth of Nazi Germany, the RMI organized the administration of newly-acquired countries and territories.

During the Night of the Long Knives, which began on 30 June 1934, 80 stormtrooper leaders and other opponents of Hitler were arrested and shot. Von Hindenberg's death on 2 August 1934 enabled Hitler to usurp his presidential powers, and his dictatorship was built upon his position as Reich president (head of state), Reich Chancellor (head of government) and Führer (leader of the Nazi Party).[6] The 9–10 November 1938 Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass) had attacks on synagogues and Jewish businesses and citizens. Over 100 were killed, and thousands were arrested.[7] Two hundred sixty-seven synagogues in Germany, Austria and the Sudetenland were destroyed; firefighters were instructed to only prevent the flames from spreading. About 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and imprisoned or interned in concentration camps. The government blamed the Jewish people for the attacks, and imposed a fine of one billion ℛℳ. After Kristallnacht, additional decrees removed the Jews from German economic and social life; those who could emigrated.[8]

Laws

After the Reichstag Fire Decree, the Enabling Act of 1933 amended the Weimar Constitution to allow Hitler and his government to enact laws (even laws violating the constitution) without going through the Reichstag. Nazi intimidation of the opposition resulted in a vote of 444 to 94.[5]

Flag law

According to the Reich flag law, Germany's national colors were black, red and white and its flag incorporated the swastika. In the words of Hitler, this was to "repay a debt of gratitude to the movement under whose symbol Germany regained its freedom, fulfilling a significant item on the program of the National Socialist Party".[9]

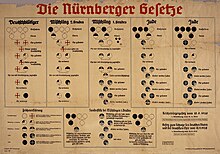

Nuremberg Laws

When Germany was completely under Nazi rule, the number and severity of laws increased. The Nuremberg Laws were announced after the annual Nazi party rally in Nuremberg on 15 September 1935. The two laws authorized arrests of, and violence against, Jews. Initially imposed in Germany, Nazi expansion during the Second World War resulted in the imposition of the Nuremberg Laws in occupied territories.[10]

Citizenship Law

The Citizenship Law specified to whom full political rights would be granted and those who would be denied them. Only citizens, with "German or related blood", received these rights; Jews, "foreigners in their own country" who were now Staatsangehörige (state subjects), were denied them.[9][11]

Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor

This law had five articles:

- Marriages between Jews and Germans or relatives were forbidden, and existing marriages of this kind were void.

- Sexual relations outside marriage between Jews and Germans or relatives were forbidden.

- Jews were not allowed to employ female German citizens or relatives as domestic servants.

- Jews were forbidden to display the national flag and/or colours

- Violations of the first article were punishable by hard labor; violations of the second article were punishable by imprisonment, and violations of the third article were punishable by fine and imprisonment.[1]

A 14 November 1935 supplemental decree defined Jewishness. No longer limited to religious beliefs, the decree classified those who followed the Jewish faith, belonged to the Jewish religion when the decree was promulgated, or later entered the Jewish religion,[12] anyone who had three or more Jewish grandparents or two Jewish grandparents and was married to a Jewish spouse and anyone who joined a Jewish community as Jewish, regardless of whether they still followed the religion.[13][13]

Nineteen hundred "special Jewish laws" emphasized Aryan morality and antisemitic stereotypes of "Jewish counter-morality".[1] Jewish lawyers and notaries had been prohibited from working for the city of Nuremberg in a 1933 decree, and Nazi ideology continue to creep into the legal system:

- The use of Jewish names for spelling in telephone delivery of telegrams was banned (22 April 1933).

- Non-Aryans could not be lay judges or jury members (13 November 1933).

- The perception that Aryan students were receiving assistance from Jews in preparing their exams must end (4 April 1935).

- The kosher slaughter of animals was prohibited.[1]

- Sports laws prohibiting Jewish boxing and public swimming[1]

For a brief period before and during the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, antisemitic laws and attacks were moderated and discriminatory signage removed.[12] Although this was regarded as an attempt by Hitler to appease the international audience and limit criticism and interference, nearly all German Jewish athletes were excluded from Olympic competition.[12]

Later antisemitic laws

According to historian Saul Friedländer, the "fateful turning point" was reached in 1938 and 1939[14] with the passage of additional laws which used economic harassment and violence to drive Jews from Germany and Austria:[14]

- Jewish physicians were de-certified, and were no longer allowed to treat German patients.

- Jews were not allowed to own gardens.

- All streets in Germany were renamed.

- Jews were prohibited from cinemas, the opera, and concerts.

- Jewish children were banned from public schools.

- Robbing Jews became legal, and Jews were forced to surrender "all jewelry of any value".[15]

Legal system

In Nazi Germany, the civil service provided a legal framework to deprive Jews of their rights.[1] Opportunities to create anti-Jewish policies were coveted and career bureaucrats came together and developed increasingly radical policies. Their familiarity with the legal system enabled them to easily manipulate it.[1] The judiciary lost its independence as it was increasingly controlled by the Nazis. Judges who did not join the National Socialist League for the Maintenance of Law were dismissed. Jewish lawyers and judges and those with socialist or other views inconvenient to the Nazi Party were removed. The fundamental legal principle became Nazi "common sense", "Whatever is good for Germany is legal".[16] The People's Court (Volksgerichtshof) was created in 1934 for people accused of political crimes. In 1938, all crimes began to be tried in the court; in 1939, its remit was expanded to include minor offenses.[17] Roland Freisler, appointed in 1942 as judge and interrogator, was infamous for "berating and belittling" defendants and lawyers.[17] Statutes were "systematically misinterpreted”, and the court has been described as committing "judicial murders".[17] Separation of defendants and lawyers was calculated to prevent communication, and defense presentations were often interrupted.[16] Courts were made up of three judges; all verdicts were final, and the convicted defendant was immediately executed. The 20 July plot in 1944 was accompanied by a series of aggressive prosecutions, and over 110 death sentences were imposed in fifty trials.[17]

Nuremberg trials

After the end of World War II, the Nuremberg trials were conducted in 1945 and 1946 to bring Nazi war criminals to justice. The Nuremberg Charter, decreeing an International Military Tribunal (IMT), was announced on 8 August 1945 to conduct 13 trials made up of judges from the United States, Great Britain, France and the Soviet Union. Article six of the charter outlines the crimes for which Nazi officials would be tried:

- Conspiracy to commit charges two, three, and four below

- Crimes against peace – participation in the planning and waging of a war of aggression in violation of international treaties

- War crimes – violations of the internationally agreed-on rules for waging war

- Crimes against humanity – murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population, before or during the war, or persecution on political, racial, or religious grounds in execution of or in connection with any crime within the jurisdiction of the tribunal, whether or not in violation of the domestic law of the country where it was perpetrated.[18]

Twenty-four Nazi officials were indicted for these crimes on 6 October 1945, including Hermann Goring (Hitler's designated heir),[citation needed] Rudolf Hess (Nazi deputy leader), Joachim von Ribbentrop (foreign minister), and Wilhelm Keitel (head of the armed forces). Verdicts included 12 death sentences, three life imprisonments, four prison terms of 10–20 years and three acquittals. Those acquitted were Hjalmar Schacht (economics minister), former vice-chancellor Franz von Papen, and Hans Fritzsche (head of press and radio).[18]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j E., Steinweis, Alan (2013). Law in Nazi Germany, The : Ideology, Opportunism, and the Perversion of Justice. Rachlin, Robert D. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 9780857457813. OCLC 861080571.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f "Nazi Law: Legally Blind".

- ^ Shirer, William L. (1960). The rise and fall of the Third Reich. New York. ISBN 978-0671624200. OCLC 1286630.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c GOLDBERG, AMOS; SERMONETA-GERTEL, SHMUEL; GREENBERG, AVNER (2017). Trauma in First Person: Diary Writing during the Holocaust. Indiana University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1zxz15p.12. ISBN 9780253029744.

- ^ a b J., Evans, Richard (2004). The coming of the Third Reich (1st US ed.). New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1594200045. OCLC 53186626.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Nazi Rule". Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- ^ "Remembering Kristallnacht". The Jerusalem Report. 2008 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Kristallnacht". Holocaust Encyclopedia.

- ^ a b Friedlander, Saul (1997). Nazi Germany and The Jews. HarperCollins, p. 142. ISBN 0-06-019042-6.

- ^ "Nurnberg Laws | Definition, Date, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- ^ Bankier, David (1992). The Germans and the Final Solution. pp. 41–42. ISBN 0-631-17968-2.

- ^ a b c "The Nuremberg Race Laws". encyclopedia.ushmm.org. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ a b Friedlander, Saul (1997). Nazi Germany and the Jews. HarperCollins. p. 149.

- ^ a b Friedlander, Saul (1997). Nazi Germany and The Jews. HarperCollins. p. 180.

- ^ Efron, Weitzman, Lehmann, John, Steven, Matthias (2004). The Jews: A History. Pearson Education Inc. pp. 410–411. ISBN 0-205-89626-X.

- ^ a b "Lawyers and Judges in Nazi Germany". www.sydneycriminallawyers.com.au. 2016-02-26. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- ^ a b c d "The "People's Court"". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- ^ a b "The Nuremberg Trials". Retrieved 2018-10-19.