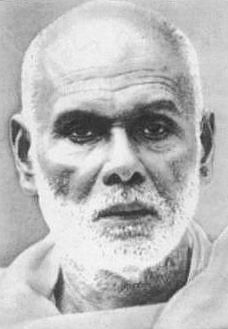

Vakkom Moulavi

Vakkom Abdul Khader Moulavi | |

|---|---|

| Born | Mohammed Abdul Khader 28 December 1873 |

| Died | 31 October 1932 (aged 58) |

| Nationality | India (formerTravancore state) |

| Other names | Vakkom Moulavi |

| Known for | islahiislamic leader, Freedom fighter,Founder and Publisher of Swadeshabhimani, Scholar, Social leader and reformer.[1] |

| Spouse | Aamina Umma |

| Children | Abdul Salam, Abdul Hai, Abdul Vahab, Abdul Kadar ( Junior), Obeidullah, Haque, Yahiya, Ameena Beevi,Sakeena, Mohammed Eeza, Mohammed Iqbal |

| Parent(s) | Aash Beevi (Mother) Muhammad Kunju (Father) |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Reformation in Kerala |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Notable people |

|

| Others |

Vakkom Mohammed Abdul Khader Moulavi (28 December 1873 - 31 October 1932) , popularly known as Vakkom Moulavi[2] was a social reformer[3], teacher, prolific writer, Muslim scholar, journalist, freedom fighter and newspaper proprietor in Travancore, a princely state of the present day Kerala, India. He was the founder and publisher of the newspaper Swadeshabhimani which was banned and confiscated by the Government of Travancore[3] in 1910 due to its criticisms against the government and the Diwan of Travancore, P. Rajagopalachari.[4]

Early life and family

Moulavi was born in 1873 in Vakkom, Chirayinkil Taluk, Thiruvananthapuram in Travancore. He was born into a prominent Muslim family Poonthran which had ancestral roots to Madurai and Hyderabad, and many of his maternal ancestors worked for the military of the state government.

His father, a prominent merchant, engaged a number of scholars from distant places, including an itinerant Arab savant, to teach him every subject he wished to learn. Moulavi made such rapid progress, that some of his teachers soon found that their stock of knowledge was exhausted and at least one of them admitted that had learnt from his student more than he could teach him. In a short time, Moulavi had learnt many languages including Arabic, Persian, Urdu, Tamil, Sanskrit and English.

In early 1900s, Moulavi was married to Haleema, daughter of Aliyar Kunju Poonthran Vilakom and Pathumma Kayalpuram. Moulavi - Haleema couple had one son Abdul Salam. Haleema died soon after the birth of their first child. A year later, Moulavi married Aamina Ummal. The couple had ten children, includes Abdul Hai, Abdul Vahab, Abdul Khader Jr. Abdul Haque, Obaidullah, Ameena, Yahiya, Sakeena, Mohammed Eeza and Mohammed Iqbal. His sons, Abdul Salam, Abdul Vahab and Mohammed Eeza were writers and scholars of Islamic studies, and Abdul Khader Jr was a writer, literary critic and journalist. One of his nephews, Vakkom Majeed, was an Indian freedom fighter and a former member of Travancore-Cochin State Assembly and another nephew, P.Habeeb Mohamed, was the first Muslim judge of the Travancore High Court of Kerala. His disciples included K.M Seethi Sahib, the former Speaker of Kerala Legislative Assembly and a social reformer among kerala Muslims.

Journalism and Swadeshabhimani

Maulavi started the Swadeshabhimani newspaper on 19 January 1905, declaring that "the paper will not hesitate to expose injustices to the people in any form", but on 26 September 1910, the newspaper and press were sealed and confiscated by the British Police, and the editor Ramakrishna Pillai was arrested and banished from Travancore to Thirunelveli.[4][5][6]

After the confiscation of the press, Moulavi concentrated more on social and cultural activities, becoming a social leader, also writing several books. Daussabah and Islam Matha Sidantha Samgraham are original works, while Imam Ghazali's Keemiya-e- Saadat, Ahlu Sunnathuwal Jammath, Islamic Sandesam, Surat-ul fathiha are translations.

Social Reformation

Moulavi is considered as one of the greatest reformers in the Kerala Muslim community, and is sometimes referred to as the "father of muslim renaissance".[7] He emphasised the religious and socioeconomic aspects much more than the ritualistic aspects of religion. He also campaigned for the need for modern education, the education of women, and the elimination of potentially bad customs among the Muslim community.[8] Influenced by the writings of Muhammad Abduh of Egypt and his reform movement, Moulavi started journals in Arabi-Malayalam and in Malayalam modelled on Al Manar.[9][10] The Muslim[3] was launched in January 1906 and was followed by Al-Islam[3](1918) and Deepika(1931). Through these publications, he tried to teach the Muslim community about the basic tenets of Islam. Al-Islam began publishing in April 1918 and played a pivotal role in Muslim renaissance in Kerala. It opposed Nerchas and Uroos festivals amongst the Muslim community, thereby attracting opposition from the orthodox ulema to the extent that they issued a fatwa declaring the reading of it as sacrilege. Financial troubles and lack of readership led to the closure of the journal within five issues, but it is regarded as the pioneer journal that attempted religious reform amongst the Mappilas of Kerala. While it was published in Malayalam language using Arabi-Malayalam script, Muslim and Deepika used Malayalam in script also.[7][11][12]

As a result of the continuous campaigning of Moulavi throughout the State, the Maharaja's Government introduced the teaching of Arabic in all state schools where there were Muslim pupils, and offered them fee concessions and scholarships. Girls were totally exempted from payment of fees. Moulavi wrote text books for children to learn Arabic, and a manual for training Arabic instructors for primary schools. At the instance of Moulavi Abdul Qadir the State Government soon instituted qualifying examinations for Arabic teachers of which he was made the chief examiner.[13]

There were many other dubious practices in the Muslim community of the time, such as the dowry system, extravagant expenditure on weddings, celebration of annual "urs" and Moharrum with bizarre unIslamic features bordering on idolatrous rituals. Moulavi launched his campaign against such practices with the help of his disciples, and with the co-operation of other learned men who shared his views and ideals.[14][15][16] As the campaign developed into a powerful movement, opposition was mounted by the Mullahs. Some issued "fatwas" that he was a "kafir", others branded him as a "Wahhabi".[citation needed]

He also tried to create unity among Muslims, starting the All Travancore Muslim Mahajanasabha[17] and Chirayinkil Taluk Muslim Samajam, and worked as the chairman of the Muslim Board of the Government of Travancore. His activities were further instrumental in the establishment of "Muslim Aikya Sangham"[18], a united Muslim forum in Eriyad, Kodungalloor for all the Muslims of the Travancore, Cochin and Malabar regions,with K M Moulavi, K M Seethi Sahib, Manappat Kunju Mohammed Haji and helped guide the Lajnathul Mohammadiyya Association of Alappuzha, Dharma Bhoshini Sabha of Kollam amongst others.[citation needed] In 1931, he founded the Islamia Publishing House, with his eldest son Abdul Salam supervising the translation into Malayalam and publication of Allama Shibli's biography of Omar Farooq in two volumes under the title Al Farooq.

See also

Further reading

- Vakkom Moulavi – (1981) Haji M. Muhammedkannu.[19]

- Vakkom Moulaviyude thiranjedutha kritikal(വക്കം മൗലവിയുടെ തിരഞ്ഞെടുത്ത കൃതികള്) (The Collected Works of Vakkom Moulavi – Malayalam) Published by Vakkom Moulavi Publications, 1979

- Muhammad Abdul Khader Moulavi, Pg 314, Modernist Islam, 1840–1940: a sourcebook By Charles Kurzman

- സ്വദേശാഭിമാനി വക്കം മൗലവി (ജീവചരിത്രം) ഡോ. ജമാല് മുഹമ്മദ് (2013), കോഴിക്കോട്: ഇസ്ലാമിക് പബ്ലിഷിംഗ് ഹൗസ്, പേജ് 216.

- ചരിത്രത്തെ സമ്മര്ദ്ദaത്തിലാക്കുന്ന ജീവചരിത്രം by പി. ശ്രീകുമാര്

See Also (Social reformers of Kerala)

- Sree Narayana Guru

- Dr. Palpu

- Kumaranasan

- Rao Sahib Dr. Ayyathan Gopalan

- Brahmananda Swami Sivayogi

- Vaghbhatananda

- Mithavaadi Krishnan

- Moorkoth Kumaran

References

- ^ Muhammed Rafeeq, T. Development of Islamic movement in Kerala in modern times (PDF). Abstract. p. 3. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ^ Koya, S. M. Mohamed. (1983). Mappilas of Malabar: Studies in Social and Cultural History. Calicut (Kerala): Sandhya Publications. pp. 80.

- ^ a b c d Gopalkrishna Gandhi (2012). "Kerala and Gandhi". Indian Literature. 56 (4): 147. JSTOR 23345936.

- ^ a b Pillai, Ramakrishna. (1911). Ende Naadukadathal (5 (2007) ed.). Kottayam (Kerala): DC Books. ISBN 81-264-1222-4.

- ^ Koshy, M. J. (1972). Constitutionalism in Travancore and Cochin. Trivandrum (Kerala): Kerala Historical Society. pp. 18–19.

- ^ Nayar, K. Balachandran (1974). In Quest of Kerala. Trivandrum (Kerala): Accent Publications. pp. 65, and 160.

- ^ a b Pg 239, Pg 345 – Proceedings of the 19th Annual conference, South India History Congress, 2000

- ^ "Leaders of Renaissance ( Social Studies Textbook,Standard X,)" (PDF). Department of School Education, Government of Kerala. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ^ Pg 67, Islam in Kerala: groups and movements in the 20th century- M. Abdul Samad,Laurel Publications, 1998

- ^ K M Bahauddin (1992). Kerala Muslims: The Long Struggle. Sahitya Pravarthaka Cooperative Society ; Modern Book Centre.

- ^ Pg 134, Journal of Kerala studies, Volume 17,University of Kerala.,1990

- ^ Malayalam Literary Survey. Kēraḷa Sāhitya Akkādami. 1984. p. 50.

- ^ Pg 36, Pg 56–58,Educational empowerment of Kerala Muslims: a socio-historical perspective By U. Mohammed, Other Books, Kozhikode

- ^ A. Sreedhara Menon (1979). Social and Cultural History of Kerala. Sterling. p. 210.

- ^ K. V. Krishna Ayyar (1966). A Short History of Kerala. Pai.

- ^ Siba Pada Sen (1979). Social and Religious Reform Movements in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Institute of Historical Studies, Calcutta, Institute of Historical Studies. p. 389.

- ^ =Asanaru Abdul Salim; Salim, P R Gopinathan Nair (2002). Educational Development in India. Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. p. 23. ISBN 9788126110391.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ SIHC 1981 PRO VOL II. Dr. Narinder Sharma (ed.). Muslim Resurgence in Kerala. p. 183. Retrieved 17 July 2019.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "The following biographies are available at the KCHR archives".