NAFTA's effect on United States employment

It has been suggested that this article be merged into North American Free Trade Agreement. (Discuss) Proposed since July 2020. |

North American Free Trade Agreement's impact on United States employment has been the object of ongoing debate since the 1994 inception of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with Canada and Mexico. NAFTA's proponents believe that more jobs were ultimately created in the USA. Opponents see the agreements as having been costly to well-paying American jobs.

Overview

The economic impacts of NAFTA have been modest. In a 2015 report, the Congressional Research Service summarized multiple studies as follows: "In reality, NAFTA did not cause the huge job losses feared by the critics or the large economic gains predicted by supporters. The net overall effect of NAFTA on the U.S. economy appears to have been relatively modest, primarily because trade with Canada and Mexico accounts for a small percentage of U.S. GDP. However, there were worker and firm adjustment costs as the three countries adjusted to more open trade and investment among their economies."[1]

In a 2003 report, the Congressional Budget Office wrote: "CBO estimates that the increased trade resulting from NAFTA has probably increased U.S. gross domestic product, but by a very small amount—probably a few billion dollars or less, or a few hundredths of a percent." CBO estimated that NAFTA added $10.3 billion to exports and $9.4 billion to imports in 2001.[2] For scale, that was roughly 10% of the trade activity with Mexico in that year.[3]

Several other studies discussed below argue that impacts on particular U.S. industries were more significant and that the U.S. labor movement was weakened by opening trade with Mexico, a lower wage country.

Job loss

This section may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. (January 2019) |

In 1987 the U.S. was the destination of 69.2% of Mexico’s exports and the U.S. accounted for 74% of Mexico’s imports. [citation needed] In 2013, the U.S. was the destination of 78.8% of exports and accounted for 49.1% of the imports to the country.[citation needed] The agricultural and manufacturing industrial sectors were the hardest hit areas by NAFTA [citation needed][clarification needed]

According to the Economic Policy Institute, an American think tank which receives significant funding from labor unions, the rise in the trade deficit with Mexico alone since NAFTA was enacted led to the net displacement of 682,900 U.S. jobs by 2010.[5] A 2003 paper released by the Economic Policy Institute noted that President George W. Bush and other proponents of trade liberalization often cited only potential job gains from increased exports. The 2003 paper noted that increases in imports ultimately displaced the production of goods that would have been made domestically by workers within the United States.[6]

According to the Economic Policy Institute's study, 61% of the net job losses due to trade with Mexico under NAFTA, or 415,000 jobs, were relatively high paying manufacturing jobs.[5] Certain states with heavy emphasis on manufacturing industries like Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Indiana, and California were significantly affected by these job losses.[5] However, in Ohio, Trade Adjustment Assistance and NAFTA-TAA identified only 14,653 jobs directly lost due to NAFTA-related reasons like relocation of U.S. firms to Mexico.[7] In Pennsylvania, Keystone Research Center attributed 38,325 in job losses in the state to trade with Mexico and Canada.[8] Since 1993, 38,325 of those job losses are directly related to trade with Mexico and Canada. Although many of these workers laid off due to NAFTA were reallocated to other sectors, the majority of workers were relocated to the service industry, where average wages are 4/5 to that of the manufacturing sector.[6]

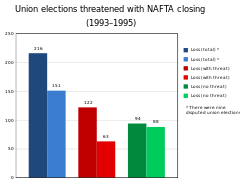

Opponents also argue that the ability for firms to increase capital mobility and flexibility has undermined the bargaining power of U.S. workers. In addition to enjoying lower tariffs for shipping goods from Mexico to the United States, multinational corporations also benefited from NAFTA's unprecedented section giving multinational corporations the right to sue governments for infringement of "investment rights".[9] According to the Economic Policy Institute, these investor protections facilitated the movement of manufacturing plants to Mexico.[10] Fifteen percent of employers in manufacturing, communication, and wholesale/distribution shut down or relocated plants due to union organizing drives since NAFTA's implementation.[11]

Job creation

U.S. employment increased over the period of 1993–2007 from 110.8 million people to 137.6 million people.[12] Specifically within NAFTA's first five years of existence, 709,988 jobs (140,000 annually), were created domestically.[13] The mid to late nineties was a period of strong economic growth in the United States. When a country is experiencing economic growth (i.e. GDP is increasing), there is usually also an increase in employment.[14] Thus, because trade liberalization can sometimes contribute to increases in GDP, it can help to bring the rate of unemployment down in a country. The U.S. experienced a 48% increase in real GDP from 1993–2005. The unemployment rate over this period was an average of only 5.1%, compared to 7.1% from 1982–1993, before NAFTA was implemented.[13] Critics of NAFTA argue that the 1990s economic boom was driven by technological change, however, and that employment growth in the 1990s would have been even greater without NAFTA.[15]

Proponents reject the claims of some that the free trade agreement is destroying the manufacturing industry and causing displacement of workers in that industry. The rate of job loss due to plant closings, a typical argument against NAFTA, showed little deviation from previous periods.[16] Also, US industrial production, in which manufacturing makes up 78%, saw an increase of 49% from 1993–2005. The period prior to NAFTA, 1982–1993, only saw a 28% increase.[13] In fact, according to NAM, National Association of Manufacturers, NAFTA has only been responsible for 10% of the manufactured goods trade deficit, something opponents criticize the agreement for exacerbating.[17] The growth of exports to Canada and Mexico accounted for a large proportion of total U.S. export gains.[18] However, the growth of exports to Canada and Mexico in percentage terms has lagged significantly behind the growth of exports to the rest of the world.[19]

According to the Democratic Leadership Council, "the most direct measurement of the impact of trade agreements on employment is the number of jobs supported by exports."[20] It is estimated that 8500 manufacturing jobs are supported by every $1 billion in US exports.[13] Because $12 billion of average annual gains in exports were created by expansion of North American trade, more than 100,000 additional US jobs were created, but this measure does not account for jobs lost due to rising imports.[13] More importantly, it has been noted that in export-oriented industries, wages are 13-16 percent higher than the national average.[13]

Others agree with the notion that there has been an increase in net jobs due to NAFTA's implementation, but also believe that these net gains are coming at the price of worker's wages.[citation needed] That is, high-paying manufacturing jobs are being lost and replaced by lower paying jobs and is causing wage deflation in certain sectors. However, during the Clinton administration, the sources of new job creation were in relatively high paid sectors and industries.[21]

See also

References

- ^ CRS-Villarreal and Fergusson-The North American Free Trade Agreement-April 16, 2015

- ^ CBO-The Effects of NAFTA on U.S.-Mexican Trade and GDP

- ^ a b U.S. Census Bureau-Trade in Goods with Mexico-Retrieved August 10, 2016

- ^ Kate Bronfenbrenner, 'We'll Close', The Multinational Monitor, March 1997, based on the study she directed, 'Final Report: The Effects of Plant Closing or Threat of Plant Closing on the Right of Workers to Organize'.

- ^ a b c Scott, Robert E. Economic Policy Institute. 3 May 2011. Retrieved 10 Nov. 2011 Heading South: U.S.-Mexico trade and job displacement after NAFTA.

- ^ a b Scott, Robert E. Economic Policy Institute. 17 Nov. 2003. Retrieved 22 Apr. 2008 The High Price of Free Trade.

- ^ Honeck, Jon (February 2004). International Trade and Job Loss in Ohio. A report from Policy Matters Ohio. Retrieved 2016-08-22.

- ^ Keystone Research Center. 2001. 28 Apr. 2008 Job Losses Due to Trade Since NAFTA Deepen Pennsylvania Manufacturing Crisis.

- ^ US Department of State. NAFTA Investor-State Arbitrations. NAFTA Investor-State Arbitrations Accessed 12 April 2010

- ^ Scott, Robert E. Economic Policy Institute. 25 Feb. 2010. Retrieved 10 Nov. 2011 Trade policy and job loss.

- ^ Woodhead, Greg. AFL-CIO. 2000. AFL-CIO Policy Department. 28 Apr. 2008 NAFTA's Seven-Year Itch: Promised Benefits Not Delivered to Workers Archived 2008-07-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ 24 Apr. 2008 NAFTA Facts. United States Trade Representative. 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Hufbauer, Gary C., and Jeffrey J. Scott. NAFTA Revisited: Achievements and Challenges. Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics, 2005.

- ^ Hubbard, Glenn, and Anthony P. O'brien. Macroeconomics. Upper Saddle River: Pearson: Prentice Hall, 2006. 233–34.

- ^ Salas, Carlos, Jeff Faux, and Robert E. Scott. Economic Policy Institute. 28 Sept. 2006. Retrieved 10 Nov. 2011 Revisiting NAFTA: Still not working for North America's workers.

- ^ Kletzer, Lori G. Journal of Economic Perspectives 12 (1998): 115–36. 25 Apr. 2008 Job Displacement.

- ^ National Association of Manufacturers. July 2005. 28 May 2008 The Truth About NAFTA:.

- ^ Thomas H. Becker, 2010, Doing Business in the New Latin America, p. 37

- ^ Travis McArthur and Todd Tucker. Public Citizen. Sept. 2010. Retrieved 10 Nov. 2011 Lies, Damn Lies, and Export Statistics: How Corporate Lobbyists Distort the Record of Flawed Trade Deals.

- ^ Datelle, David C. Democratic Leadership Council. 1 Oct. 1997. 22 Apr. 2008 NAFTA's Effect on U.S. Jobs: a Small But Positive Impact After Three Years.

- ^ DeLong, Chris; DeLong, Brad; Robinson, Sherman (May 17, 1996). "NAFTA and Jobs: Remember the 'Giant Sucking Sound'?". Brad DeLong's Homepage: Op-Eds. Archived from the original on 2012-03-13. Retrieved 2016-08-21. Adapted from the authors' article "The Case for Mexico's Rescue: The Peso Package Looks Even Better Now", which appeared in Foreign Affairs, vol. 75, no. 3 (May/June 1996), pp. 8–14.