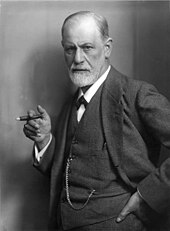

Sigmund Freud's views on homosexuality

This article has an unclear citation style. (May 2020) |

Sigmund Freud's views on homosexuality have been described as deterministic, whereas he would ascribe biological and psychological factors in explaining the principal causes of homosexuality. Sigmund Freud believed that humans are born with unfocused sexual libidinal drives, and therefore argued that homosexuality might be a deviation from this.[1] Nevertheless, he also felt that certain deeply rooted forms of homosexuality were difficult or impossible to change.[dubious – discuss][citation needed][clarification needed]

Overview

Freud's most important articles on homosexuality were written between 1905, when he published Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, and 1922, when he published "Certain Neurotic Mechanisms in Jealousy, Paranoia, and Homosexuality".[2] Freud believed that all humans were bisexual, by which he primarily meant that everyone incorporates aspects of both sexes, and that everyone is sexually attracted to both sexes. In his view, this was true anatomically and therefore also mentally and psychologically. Heterosexuality and homosexuality both developed from this original bisexual disposition.[3] As one of the causes of homosexuality, Freud mentions the distressing heterosexual experience: "Those cases are of particular interest in which the libido changes over to an inverted sexual object after a distressing experience with a normal one."[4]

Freud appears to have been undecided whether or not homosexuality was pathological, expressing different views on this issue at different times and places in his work.[citation needed] Freud frequently borrowed the term "inversion" from his contemporaries to describe homosexuality, something which in his view was distinct from the necessarily pathological perversions, and suggested that several distinct kinds might exist, cautioning that his conclusions about it were based on a small and not necessarily representative sample of patients.[5][6]

Freud derived much of his information on homosexuality from psychiatrists and sexologists such as Richard von Krafft-Ebing and Magnus Hirschfeld, and was also influenced by Eugen Steinach, a Viennese endocrinologist who transplanted testicles from straight men into gay men in attempts to change their sexual orientation. Freud stated that Steinach's research had "thrown a strong light on the organic determinants of homoeroticism",[7] but cautioned that it was premature to expect that the operations he performed would make possible a therapy that could be generally applied. In his view, such transplant operations would be effective in changing sexual orientation only in cases in which homosexuality was strongly associated with physical characteristics typical of the opposite sex, and probably no similar therapy could be applied to lesbianism.[6][8][9] In fact Steinach's method was doomed to failure because the immune systems of his patients rejected the transplanted glands, and was eventually exposed as ineffective and often harmful.[9]

Views on attempts to change homosexuality

Freud believed that homosexuals could seldom be convinced that sex with someone of the opposite sex would provide them with the same pleasure they derived from sex with someone of the same sex. Patients often pursued treatment due to social disapproval, which was not a strong enough motive for change.[citation needed]

Freud wrote in the 1920 paper The Psychogenesis of a Case of Homosexuality in a Woman, that changing homosexuality was difficult and therefore possible only under unusually favourable conditions, observing that "in general to undertake to convert a fully developed homosexual into a heterosexual does not offer much more prospect of success than the reverse."[10] Success meant making heterosexual feelings possible rather than eliminating homosexual feelings.[8]

Female homosexuality

Freud's main discussion of female homosexuality was the paper The Psychogenesis of a Case of Homosexuality in a Woman, which described his analysis of a young woman who had entered therapy because her parents were concerned that she was a lesbian.[10] Her father hoped that psychoanalysis would cure her lesbianism, but in Freud's view, the prognosis was unfavourable because of the circumstances under which the woman entered therapy, and because the homosexuality was not an illness or neurotic conflict.

Freud, therefore, told the parents only that he was prepared to study their daughter to determine what effects therapy might have. Freud concluded that he was probably dealing with a case of biologically innate homosexuality, and eventually broke off the treatment because of what he saw as his patient's hostility to men.[5][11][12]

1935 letter

In 1935, Freud wrote to a mother who had asked him to treat her son's homosexuality, a letter that would later become famous:[5]

I gather from your letter that your son is a homosexual. I am most impressed by the fact that you do not mention this term yourself in your information about him. May I question you why you avoid it? Homosexuality is assuredly no advantage, but it is nothing to be ashamed of, no vice, no degradation; it cannot be classified as an illness; we consider it to be a variation of the sexual function, produced by a certain arrest of sexual development. Many highly respectable individuals of ancient and modern times have been homosexuals, several of the greatest men among them. (Plato, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, etc). It is a great injustice to persecute homosexuality as a crime –and a cruelty, too. If you do not believe me, read the books of Havelock Ellis.

By asking me if I can help [your son], you mean, I suppose, if I can abolish homosexuality and make normal heterosexuality take its place. The answer is, in a general way we cannot promise to achieve it. In a certain number of cases we succeed in developing the blighted germs of heterosexual tendencies, which are present in every homosexual; in the majority of cases it is no more possible. It is a question of the quality and the age of the individual. The result of treatment cannot be predicted.

What analysis can do for your son runs in a different line. If he is unhappy, neurotic, torn by conflicts, inhibited in his social life, analysis may bring him harmony, peace of mind, full efficiency, whether he remains homosexual or gets changed.[13][14]

See also

Notes

- ^ Erwin, Edward (2002). The Freud Encyclopedia: Theory, Therapy, and Culture. Taylor & Francis. pp. 258–261. ISBN 978-0-415-93677-4.

- ^ Lewes 1988, p. 28

- ^ Ruse 1988, p. 22

- ^ Freud 1905, p. 48

- ^ a b c Lewes 1988

- ^ a b Freud 1991, pp. 58–59 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFreud1991 (help)

- ^ Lewes 1988, p. 58

- ^ a b Freud 1991, p. 375 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFreud1991 (help)

- ^ a b LeVay 1996, p. 32

- ^ a b Freud 1991, p. 376 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFreud1991 (help)

- ^ Freud 1991, pp. 371–400 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFreud1991 (help)

- ^ O’Connor & Ryan 1993, pp. 30–47

- ^ Freud, Sigmund. "Historical Notes: A Letter From Freud." American Journal of Psychiatry 107, no. 10 (1951): 786-787.

- ^ Freud 1992, pp. 423–424

References

- Freud, Sigmund, Hand-written letter dated 9 April 1935, published as "Historical Notes - A Letter from Freud", American Journal of Psychiatry 107, no. 10, 786–787. doi:10.1176/ajp.107.10.786

- Freud, Ernst L. (1992), Letters of Sigmund Freud, New York: Dover Publications, Inc, ISBN 0-486-27105-6

- Freud, Sigmund (1991), Case Histories II, London: Penguin, ISBN 0-14-013799-8

- Freud, Sigmund (1991), On Sexuality, London: Penguin, ISBN 0-14-013797-1

- LeVay, Simon (1996), Queer Science: The Use and Abuse of Research Into Homosexuality, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, ISBN 0262121999

- Lewes, Kenneth (1988), The Psychoanalytic Theory of Male Homosexuality, New York: New American Library, ISBN 0-452-01003-9

- O’Connor, Noreen; Ryan, Joanna (1993), Wild Desires & Mistaken Identities: Lesbianism and Psychoanalysis, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-10022-1

- Ruse, Michael (1988), Homosexuality: A Philosophical Inquiry, New York: Basil Blackwell, ISBN 0-631-15275-X