Alaric I

| Alaric | |

|---|---|

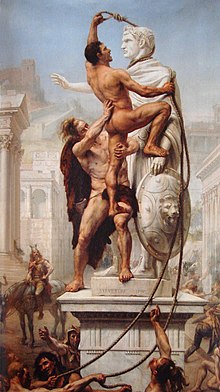

1920s artistic depiction of Alaric parading through Athens after conquering the city in 395 | |

| King of the Visigoths | |

| Reign | 395–410 |

| Coronation | 395 |

| Predecessor | Athanaric |

| Successor | Ataulf |

| Born | 370 (or 375) Peuce Island, Dobruja (present-day Romania) |

| Died | 410 Cosenza, Calabria, Italy |

| Burial | |

| Dynasty | Balt |

| Father | Unknown[1] |

| Religion | Arianism |

Alaric I (/ˈælərɪk/; Gothic: Alareiks, 𐌰𐌻𐌰𐍂𐌴𐌹𐌺𐍃, "ruler of all";[2] Latin: Alaricus; 370 (or 375) – 410 AD) was the first king of the Visigoths, from 395 to 410. He ruled the tribe that came to occupy Moesia – territory acquired a couple of decades earlier by a combined force of Goths and Alans in the wake of the dramatic Battle of Adrianople.

Alaric began his career under the Gothic soldier Gainas, and later joined the Roman army. Once an ally of Rome under the Emperor Theodosius, Alaric helped defeat the Franks. Despite losing many thousands of his men, he received little recognition from Rome for his efforts and left the Roman army disappointed. In 395, he was made elected king of the Visigoths and on several occasions marched against Rome. He is best known for his sack of Rome in 410, which marked one of several decisive events in the Western Roman Empire's eventual decline.

Early life

According to Jordanes, a 6th-century Roman bureaucrat of Gothic origin—who later turned his hand to history—Alaric was born on Peuce Island at the mouth of the Danube Delta in present-day Romania and belonged to the noble Balti dynasty of the Tervingian Goths, but there's no way to verify the veracity of this claim.[3][a] Historian Douglas Boin does not make such an unequivocal assessment about Alaric's Gothic heritage and instead claims he came from either the Tervingi or the Greunthung tribes.[5] When the Goths suffered setbacks against the Huns, they made a mass migration across the Danube, and fought a war with Rome. Alaric was probably a child during this period who grew up along Rome's periphery.[6] To this end, Alaric's upbringing was shaped by living along the border of Roman territory in a region that the Romans viewed as a veritable "backwater" and if the Roman poet Ovid's first century writings while in exile are in any way telling, the area along the Danube and Black sea where Alaric was reared constituted a land of "barbarians" and was among "the most remote in the vast world."[7][b]

Alaric's childhood in the Balkans, where the Goths had settled by way of an agreement with Theodosius, was spent in the company of veterans who had fought at the Battle of Adrianople in 378,[c] during which they had annihilated much of the Eastern army and killed Emperor Valens.[10] Imperial campaigns against the Visigoths were conducted until a treaty was reached in 382. This treaty was the first foedus on imperial Roman soil and required these semi-autonomous Germanic tribes—among whom Alaric was raised—to supply troops for the Roman army in exchange for peace, the access to cultivatable land, and freedom from Roman legal strictures.[11] Correspondingly, there was hardly a region along the Roman frontier during Alaric's day without Gothic slaves and servants of one form or another.[12] For several subsequent decades, many Goths like Alaric were "called up into regular units of the eastern field army" while others served as auxiliaries in campaigns led by Theodosius against the western usurpers Magnus Maximus and Eugenius.[13]

In Roman service and rise to Gothic leadership

A new phase in the relationship between the Goths and the empire resulted from the treaty signed in 382, as more and more Goths attained aristocratic rank from their service in the imperial army.[14] Alaric began his military career under the Gothic soldier Gainas, and later joined the Roman army.[d] He first appeared as leader of a mixed band of Goths and allied peoples, who invaded Thrace in 391 but were stopped by the half-Vandal Roman General Stilicho. While the Roman poet Claudian diminished Alaric as "a little-known menace" terrorizing southern Thrace during this time, the latter's strategic abilities and forces were formidable enough to prevent the Roman Emperor Theodosius from crossing the Maritsa River.[16] By 392, Alaric had entered Roman military service, which coincided a reduction of hostilities between Goths and Romans.[17] In 394, he led a Gothic force that helped Emperor Theodosius defeat the Frankish usurper Arbogast—fighting at the behest of Eugenius—at the Battle of Frigidus.[18] Despite sacrificing around 10,000 of his men, who had been victims of Theodosius' callous tactical decision to overwhelm the enemies front lines using Gothic foederati,[19] Alaric received little recognition from the emperor. Alaric was among the few who survived the protracted and bloody affair.[20] Many Romans considered it their "gain" and a victory that so many Goths had died during the Battle of Frigidus River.[21] Recent biographer, Douglas Boin, posits that seeing ten thousand of his (Alaric's) dead kinsman likely elicited questions about what kind of ruler Theodosius actually had been and whether remaining in direct Roman service was best for men like him.[22] Refused the reward he expected, which included a promotion to magisterium and command of regular Roman units, Alaric mutinied and began to march against Constantinople.[23]

On 17 January 395, Theodosius died of an illness, leaving his two young sons Arcadius and Honorius in Stilicho's guardianship.[24] Distinguishing himself among his people, Alaric, who had once dreamed of becoming a Roman general,[25] a rank he acquired first from Constantinople but lost, then regained in Milan (later Ravenna) and lost a second time,[26] became instead, king of the Visigoths in 395.[27] According to historian Peter Heather, it is not entirely clear in the sources if Alaric rose to prominence at the time the Goths revolted following Theodosius's death, or if he had already risen within his tribe as early as the war against Eugenius.[28][e] Whatever the circumstances, Jordanes recorded that the new king persuaded his people to "seek a kingdom by their own exertions rather than serve others in idleness."[31]

Whether or not Alaric was a member of an ancient Germanic royal clan—claimed by Jordanes and debated by historians—is less important than his emergence as a leader, the first of his kind since Fritigern.[32] Around the time Alaric became king and began asserting his authority, controversy and intrigue erupted between the Eastern and Western sides of the Roman Empire, as General Stilicho attempted to increase his position.[33] Since Theodosius's death left the Empire divided between his two sons, one taking the eastern and the other the western portion of the Empire, Stilicho sought to exploit the situation.[34] Historian Roger Collins points out that while the rivalries created by the two halves of the Empire vying for power worked to Alaric's advantage and that of his people, simply being called to authority by the Gothic people did not solve the practicalities of their needs for survival.[35] Perhaps with these concerns in mind, Alaric took his Gothic army on what historian Edward James describes as a "pillaging campaign" that began first in the East.[27]

In Greece

Alaric's forces made their way down to Athens and along the Adriatic coast, where he sought to force a new peace upon the Romans.[27] His march in 396 included passing through Thermopylae further into Greece, during which his troops plundered for the next year or so as far south as the mountainous Peloponnese peninsula.[36] Only Stilicho's surprise attack with his western field army (having sailed from Italy) stemmed the plundering as he pushed Alaric's forces north into Epirus. Despite the successful efforts of Stilicho, the east Roman official Eutropius—to whom power had passed after the death of Rufinus—expressed outrage at this unsanctioned intervention and instead of recognizing Stilicho, conferred in 397 on Alaric the title, magisterium militum, as he thought the Gothic king more malleable than the ambitious Roman general.[36]

After having received this new rank, Alaric acquired ample gold and grain to grant to his followers and negotiations were underway for a more permanent settlement.[37] Stilicho's supporters in Milan were outraged at this seeming betrayal; meanwhile, Eutropius was celebrated in 398 via a parade through Constantinople for having achieved victory over the "wolves of the North."[38][f] Fought more or less to a standstill by Stilicho, the Gothic forces under Alaric were relatively quiet for the next couple of years.[40]

Invading Italy

According to historian Michael Kulikowski, sometime in the spring of 402 Alaric decided to invade Italy, but no sources from antiquity indicate to what purpose.[41][g] Using Claudian as his source, historian Guy Halsall reports that Alaric's attack actually began in late 401, but since Stilicho was in Raetia "dealing with frontier issues" the two did not first confront one another in Italy until 402.[43] Alaric's entry into Italy followed the trek identified in the poetry of Claudian, as he crossed the peninsula' s Alpine frontier near the city of Aquileia.[44] For a period of six to nine months, there were reports of Gothic attacks along the northern Italian roads, where Alaric was spotted by Roman townspeople.[45] Along the route on Via Postumia, Alaric first encountered Stilicho.[46]

Two battles were fought. The first was at Pollentia on Easter Sunday, where Stilicho achieved an impressive victory, taking Alaric's wife and children prisoner, and more significantly, seizing much of the treasure that Alaric had amassed over the previous five years' worth of plundering.[47][h] Pursuing the retreating forces of Alaric, Stilicho offered to return the prisoners but was refused. The second battle was at Verona,[47] where Alaric was defeated for a second time. Stilicho once again offered Alaric a truce and allowed him to withdraw from Italy. Kulikowski explains this confounding, if not outright conciliatory behavior by stating, "given Stilicho's cold war with Constantinople, it would have been foolish to destroy as biddable and violent a potential weapon as Alaric might well prove to be".[47] Halsall's observations are similar, as he contends that the Roman general's "decision to permit Alaric's withdrawal into Pannonia makes sense if we see Alaric's force entering Stilicho's service, and Stilicho's victory being less total than Claudian would have us believe".[49] Perhaps more revealing is a report from the Greek historian Zosimus—writing a half a century later—that indicates an agreement was concluded between Stilicho and Alaric in 405, which suggests Alaric being in "western service at that point", likely stemming from arrangements made back in 402.[50][i] Between 404 and 405, Alaric remained in one of the four Pannonian provinces, from where he could "play East off against West while potentially threatening both".[47]

Fate was not kind to the Empire, as "Alaric’s return to the north-west Balkans brought only temporary respite to Italy, for in 405 another substantial body of Goths and other barbarians, this time from outside the empire, crossed the middle Danube and advanced into northern Italy, where they plundered the countryside and besieged cities and towns" under their leader Radagaisus.[52] Although the imperial government was struggling to muster enough troops to contain these barbarian invasions, Stilicho managed to stifle the threat posed by the tribes under Radagaisus, when the latter split his forces into three separate groups. Stilicho cornered Radagaisus near Florence and starved the invaders into submission.[52][j] Meanwhile, Alaric—bestowed with codicils of magister militum by Stilicho and now supplied by the West—awaited for one side or the other to incite him to action as Stilicho faced further difficulties from more barbarians.[54]

Second invasion of Italy

Sometime in 406 and into 407, another assemblage of barbarians, consisting primarily of Vandals, Sueves and Alans, crossed the Rhine into Gaul while at the same time a rebellion—under a common soldier named Constantine—occurred in Britain and spread to Gaul.[55] Burdened by so many enemies, Stilicho's position was strained. During this crisis in 407, Alaric again marched on Italy, taking a position in Noricum (modern Austria), where he demanded a sum of 4,000 pounds of gold lest he embark again on a full-scale invasion. At this point, Stilicho, whose earlier efforts to deal with the usurper Constantine had failed, convinced the Western Emperor Honorius and the Roman senate—who begrudgingly agreed[56]—to pay the sum and unleash Alaric's forces on their new enemy.[57] Despite how sensible Stilicho’s plan was in the grand scheme of things, since he had correctly evaluated the dangers, arguing for Alaric's intervention after having failed to contain the threat to Rome, fatally weakened his standing.[57] Twice Stilicho had allowed Alaric to escape his grasp and despite having also stopped Radagaisus, who made it all the way to the outskirts of Florence, the Roman general now came under suspicion.[58]

In 408, Western Emperor Honorius ordered the execution of Stilicho and his family, in response to rumors that the general had made a deal with Alaric.[k] While Stilicho had been murdered, so too had his loyal supporters and many thousands of barbarian auxiliaries, along with their wives and children, those that remained alive or escaped joined Alaric at Noricum.[60] Rome had made itself more vulnerable as a result and Alaric now once again made demands on Honorius for an unknown sum of gold and for the return of the civilian dependent hostages belonging to his new followers—if they remained alive.[61]

When Alaric was rebuffed, he led his force of around 30,000 men—many newly enlisted and understandably motivated—on a march toward Rome to avenge their murdered families.[62] Crossing the Julian Alps in September 408, Alaric stood before the walls of Rome (now with no capable general like Stilicho as a defender) and began a strict blockade. No blood was shed this time; Alaric relied on hunger as his most powerful weapon. When the ambassadors of the Senate, entreating for peace, tried to intimidate him with hints of what the despairing citizens might accomplish, he laughed and gave his celebrated answer: "The thicker the hay, the easier mowed!" After much bargaining, the famine-stricken citizens agreed to pay a ransom of 5,000 pounds of gold, 30,000 pounds of silver, 4,000 silken tunics, 3,000 hides dyed scarlet, and 3,000 pounds of pepper.[63] Along came 40,000 freed Gothic slaves. Thus ended Alaric's first siege of Rome.[51]

After having provisionally agreed to the terms offered by Alaric for lifting the blockade, Honorius recanted; historian A.D. Lee highlights that one of the points of contention for the emperor was Alaric's expectation of being named head of the Roman Army, a post Honorius was not prepared to grant to Alaric.[64] When this title was not bestowed onto Alaric, he proceeded to not only "besiege Rome again in late 409, but also to proclaim a leading senator, Priscus Attalus, as a rival emperor, from whom Alaric then received the appointment" he desired.[64] Meanwhile, Alaric's newly appointed "emperor" Attalus, who seems not to have known the limits of his power or understand his dependence on Alaric, failed to take the latter's advice and lost the grain supply in Africa to a pro-Honorian comes Africae, Heraclian.[65] Then, sometime in 409, Attalus—accompanied by Alaric—marched on Ravenna and after receiving unprecedented terms and concessions from the legitimate emperor Honorius, refused him and instead, demanded that Honorius be deposed and exiled.[65] Fearing for his safety, Honorius made preparations to flee to Ravenna when a ship carrying 4,000 troops arrived from Constantinople, restoring his resolve.[64] Now that it was clear Honorius no longer needed to negotiate, Alaric (regretting his choice of puppet emperor) deposed him, perhaps to re-open negotiations with Ravenna.[66]

Sack of Rome

Negotiations with Honorius might have succeeded had it not been for the influence of another Goth, Sarus, an Amali, and therefore hereditary enemy of Alaric and his house.[51] Why Sarus, who had been in imperial service for years under Stilicho, intervened at this moment remains a mystery, but Alaric interpeted this attack as Ravenna-directed and as bad faith from Honorius. No longer would negotiations suffice for Alaric, as his patience had reached its end, which led him to march on Rome for a third and final time.[67]

On 24 August 410, Alaric and his forces began the sack of Rome, an assault that lasted three days.[68] After hearing reports that Alaric had entered the city—possibly aided by Gothic slaves inside—there were reports that Emperor Honorius (safe in Ravenna) broke into "wailing and lamentation" but quickly calmed once "it was explained to him that it was the city of Rome that had met its end and not 'Roma'," his pet fowl.[68] Writing from Bethlehem, St. Jerome (Letter 127.12, to Principia)[l] lamented: "A dreadful rumour reached us from the West. We heard that Rome was besieged, that the citizens were buying their safety with gold . . . The city which had taken the whole world was itself taken; nay, it fell by famine before it fell to the sword."[68] Nonetheless, Christian apologists also cited how Alaric ordered that anyone who took shelter in a Church was to be spared.[69][m] When liturgical vessels were taken from the basilica of St. Peter and Alaric heard of this, he ordered them returned and had them ceremoniously restored in the church.[70] If the account from the historian Orosius can be seen as accurate, there was even a celebratory recognition of Christian unity by way of a procession through the streets where Romans and barbarians alike "raised a hymn to God in public"; historian Edward James concludes that such stories are likely more political rhetoric of the "noble" barbarians than a reflection of historical reality.[70]

According to historian Patrick Geary, Roman booty was not the focus of Alaric's sack of Rome but that he had come for needed food supplies.[71][n] Historian Stephen Mitchell asserts that Alaric's followers seemed incapable of feeding themselves and relied on provisions "supplied by the Roman authorities."[72] Whatever Alaric's intentions were cannot be known entirely, but Kulikowski certainly sees the issue of available treasure in a different light, writing that "For three days, Alaric’s Goths sacked the city, stripping it of the wealth of centuries."[67] The barbarian invaders were not gentle in their treatment of property as substantial damage was still evident into the sixth century.[70] Certainly the Roman world was shaken by the fall of the Eternal City to barbarian invaders, but as Guy Halsall emphasizes, "Rome’s fall had less striking political effects. Alaric, unable to treat with Honorius, remained in the political cold."[69] Kulikowski sees the situation similarly, commenting:

But for Alaric the sack of Rome was an admission of defeat, a catastrophic failure. Everything he had hoped for, had fought for over the course of a decade and a half, went up in flames with the capital of the ancient world. Imperial office, a legitimate place for himself and his followers inside the empire, these were now forever out of reach. He might seize what he wanted, as he had seized Rome, but he would never be given it by right. The sack of Rome solved nothing and when the looting was over Alaric’s men still had nowhere to live and fewer future prospects than ever before.[67]

Still, the importance of Alaric cannot be "overestimated" according to Halsall, since he had desired and obtained a Roman command even though he was a barbarian; his real misfortune was being caught between the rivalry of the Eastern and Western empires and their court intrigue.[73] According to historian Peter Brown, when one compares Alaric with other barbarians, "he was almost an Elder Statesman."[74] Nonetheless, Alaric's respect for Roman institutions as a former servant to its highest office did not stay his hand in violently sacking the city that had for centuries exemplified Roman glory, leaving behind physical destruction and social disruption, while Alaric took clerics and even the emperor’s sister, Galla Placidia, with him when he left the city.[70] More than the city of Rome itself was victim to the forces under Alaric, but the remainder of Italy, as Procopius (Wars 3.2.11–13) writing in the sixth-century later relates:

For they destroyed all the cities which they captured, especially those south of the Ionian Gulf, so completely that nothing has been left to my time to know them by, unless, indeed, it might be one tower or gate or some such thing which chanced to remain. And they killed all the people, as many as came in their way, both old and young alike, sparing neither women nor children. Wherefore even up to the present time Italy is sparsely populated.[75]

Whether Alaric's forces wrought the level of destruction described by Procopius or not cannot be known, but evidence speaks to the subsequent population decrease, as the number of people on the food dole dropped from 800,000 in 408 to 500,000 by 419.[76] Rome's fall to the barbarians was as much a psychological blow to the empire as anything else, since some Romans citizens saw the collapse resultant from the conversion to Christianity, while Christian apologists like Augustine (writing City of God) responded in turn.[77] Lamenting Rome's capture, famed Christian theologian Jerome, wrote how "day and night" he could not stop thinking of everyone's safety, and moreover, how Alaric had extinguished "the bright light of all the world."[78] Some contemporary Christian observers even saw Alaric—himself a Christian—as God's wrath upon a still pagan Rome.[79]

Death and aftermath

Not only had Rome's sack been a significant blow to the Roman people's morale, they had also endured two years' worth of trauma brought about by fear, hunger (consequent the blockades), and illness.[80] However, the Goths were not long in the city of Rome, as only three days after the sack, Alaric marched his men south to Campania, from where he intended to sail to Sicily—probably to obtain grain and other supplies—when a storm destroyed his fleet.[81] During the early months of 411, while on his northward return journey through Italy, Alaric took ill and died at Consentia in Bruttium.[81] His cause of death was likely fever,[82][o] and his body was, according to legend, buried under the riverbed of the Busento in accordance with the pagan practices of the Visigothic people. The stream was temporarily turned aside from its course while the grave was dug, wherein the Gothic chief and some of his most precious spoils were interred. When the work was finished, the river was turned back into its usual channel and the captives by whose hands the labor had been accomplished were put to death that none might learn their secret.[83][p]

Alaric was succeeded in the command of the Gothic army by his brother-in-law, Ataulf,[84] who married Honorius' sister Galla Placidia three years later.[85] Following in the wake of Alaric's leadership, which Kulikowski claims, had given his people "a sense of community that survived his own death...Alaric’s Goths remained together inside the empire, going on to settle in Gaul. There, in the province of Aquitaine, they put down roots and created the first autonomous barbarian kingdom inside the frontiers of the Roman empire."[86] The Goths were able to settle in Aquitaine only after Honorius granted the once Roman province to them; territory he divested sometime in 418 or 419.[87] Not long after Alaric's exploits in Rome and Athaulf's settlement in Aquitaine, there is a "rapid emergence of Germanic barbarian groups in the West" who begin controlling many western provinces.[88] These barbarian peoples included: Vandals in Spain and Africa, Visigoths in Spain and Aquitaine, Burgundians along the upper Rhine and southern Gaul, and Franks on the lower Rhine and in northern and central Gaul.[88]

Sources

The chief authorities on the career of Alaric are: the historian Orosius and the poet Claudian, both contemporary, neither disinterested; Zosimus, a historian who lived probably about half a century after Alaric's death; and Jordanes, a Goth who wrote the history of his nation in 551, basing his work on Cassiodorus's Gothic History. The legend of Alaric's burial in the Buzita River comes from Jordanes.

See also

References

Notes

- ^ To a large extent, Alaric's kin were largely comprised by Tervingi, with whom Constantine had concluded a lasting peace in the 330s.[4]

- ^ Ovid never singled out any particular barbarian group and at the time of his writings, was referencing the ethnic Sarmatians, Getae, Dacians and Thracians.[8]

- ^ Many of Rome's leading officers and some of their most elite fighting men died during the battle which struck a major blow to Roman prestige and the Empire's military capabilities.[9]

- ^ Alaric had a fascination for the 'golden age' of Rome and insisted on his tribesmen calling him 'Alaricus'.[15]

- ^ Heather surmises that Alaric's participation in the earlier revolt that followed Maximus' defeat and his "command of Gothic troops on the Eugenius campaign suggest...a noble steadily advancing his prestige among the Goths settled in the Balkans by Theodosius."[29] Kulikowski has heartburn with implying that Alaric held an important position among the Goths before 395 since the sources do not make it clear if Alaric’s “desire for a generalship" was a means to legitimize himself "further within a Gothic following,” or whether he was simply an ambitious man, who was at heart, “essentially a Roman soldier.” Kulikowski adds that trying to determine either “depends upon our own previous assumptions, not upon the evidence.”[30]

- ^ This victory celebration included recognizing Eutropius's part in allowing Roman troops to be reinforced by Goths, who jointly ejected the Huns from nearby Armenia.[39]

- ^ Some lines from the Roman poet Claudian inform us that he heard a voice proceeding from a sacred grove, "Away with delay, Alaric; boldly cross the Italian Alps this year and thou shalt reach the city."[42]

- ^ Stilicho's enemies later reproached him for not having finished off the enemy by slaying them in their entirety.[48]

- ^ While Alaric had not penetrated into the city, his invasion of Italy still produced important results. It caused the imperial residence to be transferred from Milan to Ravenna, and necessitated the withdrawal of Legio XX Valeria Victrix from Britain.[51]

- ^ Historian Walter Goffart points out that while many sources identify Radagaisus as an Ostrogoth, he and his forces were likely composed of "odds and ends of peoples who crossed into the empire" and that their documented numbers have been inflated.[53]

- ^ Despite skillful maneuvering against the Goths, historian J.M. Wallace-Hadrill explains that Stilicho could not endear himself to the Romans, even though he had rescued Rome on two occasions before it fell to Alaric. The reasons he remained "the scapegoat of Roman writers" were many; including that they saw Stilicho as "the man who "sold the pass." Wallace-Hadrill adds, "Partly, it seems, because he (Stilicho) was ready to compromise with the Goths in an attempt to wrest the much-coveted eastern parts of Illyricum from the control of Constantinople. Partly, too, because his concentration on Italian and Balkan affairs left Gaul open to invasion. Partly because his defense policy proved costly to the senatorial class. But most of all, perhaps, because to the Romans, he signified the arrival of Arianism," a belief system that Western Catholics found sacrilegious.[59]

- ^ See the New Advent source here: https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/3001127.htm

- ^ Evidently the piety and restraint of the barbarian soldiers under Alaric, despite their adherence to Arianism, was less pagan in the eyes of Christian writers than the practices of the Romans themselves.[68]

- ^ Geary also contends that Alaric had the long term intention to lead his people to North Africa, much like the later Vandals would do.[71]

- ^ Scholars have often wondered about the cause of King Alaric's death. As recent as 2016, Francesco Galassi and his colleagues pored over all the historical, medical and epidemiological sources they could find about Alaric's death, and concluded that the underlying cause was malaria. For further information, see: "The sudden death of Alaric I (c. 370–410 AD), the vanquisher of Rome: A tale of malaria and lacking immunity." Francesco M. Galassi, Raffaella Bianucci, Giacomo Gorini, Giacomo M. Paganottie, Michael E. Habicht, Frank J. Rühli. European Journal of Internal Medicine June 2016 Volume 31, Pages 84–87. https://www.ejinme.com/article/S0953-6205(16)00067-4/abstract

- ^ A similar story is told of the Decebalus Treasure, buried under a river in 106 AD. These burials repeat Scythian models from the Lower Danube and the Black Sea. See the following Spanish language source: Alarico I (in Spanish), Diccionario biográfico español, Luis Agustín García Moreno, Real Academia de la Historia.

Citations

- ^ Wolfram 1997, p. 90.

- ^ Harder 1986, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Boin 2020, p. 31.

- ^ Kulikowski 2006, p. 31.

- ^ Boin 2020, p. 14.

- ^ Boin 2020, pp. 14–15, 37.

- ^ Boin 2020, p. 15.

- ^ Boin 2020, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Halsall 2007, p. 179.

- ^ Kulikowski 2006, p. 11.

- ^ Halsall 2007, pp. 179–180.

- ^ Boin 2020, p. 19.

- ^ Kulikowski 2006, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Kulikowski 2006, p. 155.

- ^ Bayless 1976, pp. 65–67.

- ^ Boin 2020, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Boin 2020, p. 53.

- ^ Bauer 2010, pp. 72–74.

- ^ Boin 2020, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Boin 2020, p. 94.

- ^ Boin 2020, p. 97.

- ^ Boin 2020, p. 103.

- ^ Kulikowski 2019, p. 125.

- ^ Burns 2003, p. 335.

- ^ Burns 2003, p. 336.

- ^ Burns 2003, p. 367.

- ^ a b c James 2014, p. 54.

- ^ Heather 1991, p. 197.

- ^ Heather 1991, p. 198.

- ^ Kulikowski 2002, p. 79.

- ^ Jordanes 1915, p. 92 [XXIX.147].

- ^ Collins 1999, p. 54.

- ^ Heather 2013, pp. 153–160.

- ^ McEvoy 2013, p. 142.

- ^ Collins 1999, pp. 54–55.

- ^ a b Kulikowski 2019, p. 126.

- ^ Kelly 2009, p. 52.

- ^ Kelly 2009, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Kelly 2009, p. 53.

- ^ Halsall 2007, p. 200.

- ^ Kulikowski 2019, p. 122.

- ^ Claudian 1922, p. 165 [XXVI.545].

- ^ Halsall 2007, p. 201.

- ^ Boin 2020, p. 139.

- ^ Boin 2020, p. 140.

- ^ Boin 2020, pp. 140–141.

- ^ a b c d Kulikowski 2019, p. 135.

- ^ Bunson 1995, p. 12.

- ^ Halsall 2007, pp. 201–202.

- ^ Halsall 2007, p. 202.

- ^ a b c Hodgkin 1911, p. 471.

- ^ a b Lee 2013, p. 112.

- ^ Goffart 2006, p. 78.

- ^ Kulikowski 2006, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Kulikowski 2006, p. 171.

- ^ Lee 2013, pp. 112–113.

- ^ a b Kulikowski 2006, p. 172.

- ^ Boin 2020, p. 148.

- ^ Wallace-Hadrill 2004, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Kulikowski 2006, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Kulikowski 2006, p. 173.

- ^ Heather 2005, p. 224.

- ^ Norwich 1988, p. 134.

- ^ a b c Lee 2013, p. 113.

- ^ a b Kulikowski 2006, p. 175.

- ^ Kulikowski 2006, p. 176.

- ^ a b c Kulikowski 2006, p. 177.

- ^ a b c d James 2014, p. 57.

- ^ a b Halsall 2007, p. 216.

- ^ a b c d James 2014, p. 58.

- ^ a b Geary 1988, p. 70.

- ^ Mitchell 2007, p. 98.

- ^ Halsall 2007, p. 217.

- ^ Brown 2000, p. 286.

- ^ James 2014, p. 59.

- ^ Lançon 2001, pp. 14, 119.

- ^ Lee 2013, p. 114.

- ^ Boin 2020, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Burns 1994, p. 233.

- ^ Lançon 2001, p. 39.

- ^ a b Mitchell 2007, p. 101.

- ^ Durschmied 2002, p. 401.

- ^ Hodgkin 1911, pp. 471–472.

- ^ Lee 2013, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Bunson 1995, p. 53.

- ^ Kulikowski 2006, p. 158.

- ^ Boin 2020, p. 176.

- ^ a b Mitchell 2007, p. 110.

Bibliography

- Bauer, Susan Wise (2010). The History of the Medieval World: From the Conversion of Constantine to the First Crusade. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-39305-975-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bayless, William N. (1976). "The Visigothic Invasion of Italy in 401". The Classical Journal. 72 (1): 65–67. JSTOR 3296883.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bradley, Henry (1888). The Goths: from the Earliest Times to the End of the Gothic Dominion in Spain. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Boin, Douglas (2020). Alaric the Goth: An Outsider’s History of the Fall of Rome. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0-39363-569-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Brown, Peter (2000). Augustine of Hippo: A Biography. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22835-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bunson, Matthew (1995). A Dictionary of the Roman Empire. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19510-233-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Burns, Thomas (1994). Barbarians within the Gates of Rome: A Study of Roman Military Policy and the Barbarians, CA. 375–425 A.D. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-25331-288-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Burns, Thomas (2003). Rome and the Barbarians, 100 B.C.–A.D. 400. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-80187-306-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Claudian (1922). Claudian II. Translated by Maurice Platnauer. London: W. Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-67499-151-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Collins, Roger (1999). Early Medieval Europe, 300–1000. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 978-0-31221-885-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Durschmied, Erik (2002). From Armageddon to the Fall of Rome. London: Coronet Books. ISBN 978-0-34082-177-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Geary, Patrick J. (1988). Before France and Germany: The Creation & Transformation of the Merovingian World. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19504-458-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Goffart, Walter (2006). Barbarian Tides: The Migration Age and the Later Roman Empire. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-81222-105-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Halsall, Guy (2007). Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West, 376–568. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52143-543-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harder, Kelsie B. (1986). Names and Their Varieties: A Collection of Essays in Onomastics. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-81915-233-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Heather, Peter (1991). Goths and Romans, 332–489. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19820-234-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Heather, Peter (2005). The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19515-954-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Heather, Peter (2013). The Restoration of Rome: Barbarian Popes and Imperial Pretenders. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19936-851-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - James, Edward (2014). Europe's Barbarians, AD 200–600. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-58277-296-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jordanes (1915). The Gothic History of Jordanes. Translated by Charles C. Mierow. London: Oxford University Press. OCLC 463056290.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kelly, Christopher (2009). The End of Empire: Attila the Hun and the Fall of Rome. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-39333-849-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kulikowski, Michael (2002). "Nation versus Army: A Necessary Contrast?". In Andrew Gillett (ed.). On Barbarian Identity: Critical Approaches to Ethnicity in the Early Middle Ages. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. ISBN 2-503-51168-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kulikowski, Michael (2006). Rome's Gothic Wars: From the Third Century to Alaric. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84633-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kulikowski, Michael (2019). The Tragedy of Empire: From Constantine to the Destruction of Roman Italy. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-67466-013-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lançon, Bertrand (2001). Rome in Late Antiquity: AD 312–609. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41592-975-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lee, A. D. (2013). From Rome to Byzantium AD 363 to 565: The Transformation of Ancient Rome. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-74863-175-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McEvoy, Meaghan (2013). Child Emperor Rule in the Late Roman West, AD 367–455. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19164-210-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mitchell, Stephen (2007). A History of the Later Roman Empire, AD 284–641. Oxford and Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Norwich, John Julius (1988). Byzantium: The Early Centuries. London: Viking. ISBN 978-0-67080-251-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wallace-Hadrill, J. M. (2004). The Barbarian West, 400–1000. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-63120-292-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wolfram, Herwig (1997). The Roman Empire and its Germanic Peoples. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08511-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Online

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Hodgkin, Thomas (1911). "Alaric". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 470–472.

External links

- Alaric I

- Edward Gibbon, History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Chapter 30 and Chapter 31.

- The Legend of Alaric's Burial

- For a modern-day novel exploring the historical sources relating to Alaric's riverbed grave see Alaric's Gold by Robert Fortune