The Gay Science

| |

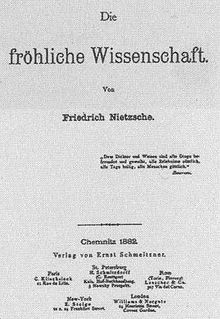

| Author | Friedrich Nietzsche |

|---|---|

| Original title | Die fröhliche Wissenschaft |

| Language | German |

| Published | first edition in 1882, second edition in 1887 |

| Publication place | Germany |

| Preceded by | Idylls from Messina (1881) |

| Followed by | Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883–1885) |

The Gay Science (Template:Lang-de), occasionally translated as The Joyful Wisdom or The Joyous Science is a book by Friedrich Nietzsche, first published in 1882 and followed by a second edition, which was published after the completion of Thus Spoke Zarathustra and Beyond Good and Evil, in 1887. This substantial expansion includes a fifth book and an appendix of songs. It was noted by Nietzsche to be "the most personal of all [his] books", and contains the greatest number of poems in any of his published works.

Title

The book's title, in the original German and in translation, uses a phrase that was well-known at the time in many European cultures and had specific meaning.

One of its earliest literary uses is in Rabelais's Gargantua and Pantagruel ("gai sçavoir"). It was derived from a Provençal expression (gai saber) for the technical skill required for poetry-writing. The expression proved durable and was used as late as 19th century American English by Ralph Waldo Emerson and E. S. Dallas. It was also used in deliberately inverted form, by Thomas Carlyle in "the dismal science", to criticize the emerging discipline of economics by comparison with poetry.

The book's title was first translated into English as The Joyful Wisdom, but The Gay Science has become the common translation since Walter Kaufmann's version in the 1960s. Kaufmann cites The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (1955) that lists "The gay science (Provençal gai saber): the art of poetry."

In Ecce Homo, Nietzsche refers to the poems in the Appendix of The Gay Science, saying they were

... written for the most part in Sicily, are quite emphatically reminiscent of the Provençal concept of gaia scienza—that unity of singer, knight, and free spirit which distinguishes the wonderful early culture of the Provençals from all equivocal cultures. The very last poem above all, "To the Mistral", an exuberant dancing song in which, if I may say so, one dances right over morality, is a perfect Provençalism.

This alludes to the birth of modern European poetry that occurred in Provence around the 11th century, whereupon, after the culture of the troubadours fell into almost complete desolation and destruction due to the Albigensian Crusade (1209–1229), other poets in the 14th century ameliorated and thus cultivated the gai saber or gaia scienza. In a similar vein, in Beyond Good and Evil Nietzsche observed that,

... love as passion—which is our European speciality—[was invented by] the Provençal knight-poets, those magnificent and inventive human beings of the "gai saber" to whom Europe owes so many things and almost owes itself.[1]

The original English translation as The Joyful Wisdom could be considered more comprehensible to the modern reader given new connotations in English usage for both "gay" and "science" in the last quarter of the twentieth century. However, it could be considered flawed in poorly reflecting the then still-current use of the phrase in its original meaning for poetry, which Nietzsche was deliberately evoking, poorly reflecting the Provencal and French origins of the phrase, and in poorly translating the German. The German fröhliche can be translated "happy" or "joyful", cognate to the original meanings of "gay" in English and other languages. However Wissenschaft never indicates "wisdom" (wisdom = Weisheit), but a propensity toward any rigorous practice of a poised, controlled, and disciplined quest for knowledge. This word is typically translated to English as "science", both in this broader meaning and for the specific sets of disciplines now called "sciences" in English. The term "science" formerly had a similarly broad connotation in English, referring to useful bodies of knowledge or skills, from the Latin scientia.

Content

The book is usually placed within Nietzsche's middle period, during which his work extolled the merits of science, skepticism, and intellectual discipline as routes to mental freedom. The affirmation of the Provençal tradition (invoked through the book's title) is also one of a joyful "yea-saying" to life.

In The Gay Science, Nietzsche experiments with the notion of power but does not advance any systematic theory.

Eternal recurrence

The book contains Nietzsche's first consideration of the idea of the eternal recurrence, a concept which would become critical in his next work Thus Spoke Zarathustra and underpins much of the later works.[2]

What if some day or night a demon were to steal after you into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: 'This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more' ... Would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke thus? Or have you once experienced a tremendous moment when you would have answered him: 'You are a god and never have I heard anything more divine.'[3]

"God is dead"

Here is also the first occurrence of the famous formulation "God is dead", first in section 108.

After Buddha was dead, people

showed his shadow for centuries afterwards in a

cave,—an immense frightful shadow. God is dead:

but as the human race is constituted, there will

perhaps be caves for millenniums yet, in which

people will show his shadow.—And we—we have

still to overcome his shadow![4]

Section 125 depicts the parable of the madman who is searching for God. He accuses us all of being the murderers of God. "'Where is God?' he cried; 'I will tell you. We have killed him—you and I. All of us are his murderers..."

Notes

References

- Kaufmann, Walter, Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist, Princeton University Press, 1974.

- The Gay Science: With a Prelude in Rhymes and an Appendix of Songs by Friedrich Nietzsche; translated, with commentary, by Walter Kaufmann (Vintage Books, March 1974, ISBN 0-394-71985-9)

- Pérez, Rolando. Towards a Genealogy of the Gay Science: From Toulouse and Barcelona to Nietzsche and Beyond. eHumanista/IVITRA. Volume 5, 2014.

External links

- Die fröhliche Wissenschaft at Nietzsche Source

- Oscar Levy's 1924 English edition, trans. Thomas Common at the Internet Archive

The Gay Science public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Gay Science public domain audiobook at LibriVox