Metairie Cemetery

Metairie Cemetery | |

Monuments at Metairie Cemetery | |

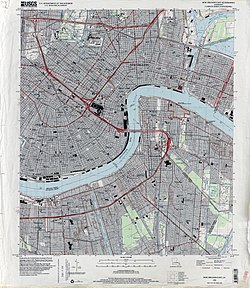

| Location | Junction of I-10 and Metairie Road, New Orleans, La. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 29°59′9″N 90°7′4″W / 29.98583°N 90.11778°W |

| Built | 1872 |

| Architect | Benjamin Morgan Harrod |

| Architectural style | Italianate, Classical Revival, Gothic Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 91001780[1] |

| Added to NRHP | December 6, 1991 |

Metairie Cemetery is a cemetery[2] in New Orleans, Louisiana, United States. The name has caused some people to mistakenly presume that the cemetery is located in Metairie, Louisiana; but it is located within the New Orleans city limits, on Metairie Road (and formerly on the banks of the since filled-in Bayou Metairie).

History

This site was previously a horse racing track, Metairie Race Course, founded in 1838.

The race track was the site of the famous Lexington-Lecomte Race, April 1, 1854, billed as the "North against the South" race. Former President Millard Fillmore attended. While racing was suspended because of the American Civil War, it was used as a Confederate Camp (Camp Moore) until David Farragut took New Orleans for the Union in April 1862. Metairie Cemetery was built upon the grounds of the old Metairie Race Course after it went bankrupt.

The race track, which was owned by the Metairie Jockey Club, refused membership to Charles T. Howard, a local resident who had gained his wealth by starting the first Louisiana State Lottery. After being refused membership, Howard vowed that the race course would become a cemetery. After the Civil War and Reconstruction, the track went bankrupt and Howard was able to see his curse come true. Today, Howard is buried in his tomb located on Central Avenue in the cemetery, which was built following the original oval layout of the track itself. Mr. Howard died in 1885 in Dobbs Ferry, New York when he fell from a newly purchased horse.[citation needed]

Undoubtedly the Metairie Cemetery is destined to be the great Necropolis of the South. As far as its location, ornaments, care and poetry are concerned, we say that this great city of the dead is unrivaled.

— Staff writer, "All Saints' Day: Yesterday's Visitations at the Homes of the Dead", New Orleans Daily Picayune (November 2, 1877)

Metairie Cemetery was previously owned and operated by Stewart Enterprises, Inc., of Jefferson, Louisiana. However, in December 2013, Service Corporation International bought Metairie Cemetery and other Stewart locations.

Sights

Metairie Cemetery has the largest collection of elaborate marble tombs and funeral statuary in the city.

One of the most famous is the Army of Tennessee, Louisiana Division monument, a monumental tomb of Confederate soldiers of the American Civil War. The monument includes two notable works by sculptor Alexander Doyle (1857–1922):

- Atop the tomb is an 1877 equestrian statue of General Albert Sidney Johnston on his horse "Fire-eater", holding binoculars in his right hand. General Johnston was for a time entombed here, but the remains were later removed to Texas.

- To the right of the entrance to the tomb is an 1885 life size statue represents a Confederate officer about to read the roll of the dead during the American Civil War. The statue is said to be modeled after Sergeant William Brunet of the Louisiana Guard Battery, but is intended to represent all Confederate soldiers.

Other notable monuments in Metairie Cemetery include:

- the pseudo-Egyptian pyramid;

- Laure Beauregard Larendon's tomb, which features Moorish details and beautiful stained glass;[3]

- the former tomb of Storyville madam Josie Arlington;

- the Moriarty tomb with a marble monument with a height of 60 feet (18 m) tall, which required the construction of a temporary special spur railroad line to transport the monument's building materials to the cemetery; and

- the memorial of 19th-century police chief David Hennessy, whose murder sparked a riot.

The initial construction of at least one of these elaborate final resting places – restaurateur Ruth Fertel's mausoleum – is estimated to have cost between $125,000 to $500,000 (in late 20th century dollars).[4]

List of notable and celebrity burials

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2020) |

- Algernon Sidney Badger, New Orleans government official during and after Reconstruction[5]

- T. L. Bayne, first Tulane University football coach and organizer of first football game in New Orleans

- P. G. T. Beauregard, Confederate General, former Superintendent at West Point

- Tom Benson, owner of New Orleans Saints and New Orleans Pelicans[6]

- John Bernecker, stunt performer

- Renato Cellini, operatic conductor

- William C. C. Claiborne, first U.S. Governor of Louisiana

- Marguerite Clark, stage and film actress

- Lewis Strong Clarke, sugar planter and Republican politician[7]

- Isaac Cline was the chief meteorologist at the Galveston, Texas office of the US Weather Bureau from 1889 to 1901. In that role, he became an integral figure in the devastating Galveston Hurricane of 1900.

- Hamilton D. Coleman was a businessman who held Louisiana's 2nd congressional district seat from 1889 to 1891. He was the last Republican member of the U.S. House from Louisiana until 1973.

- Al Copeland, founder of Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen

- Nathaniel Cortlandt Curtis Jr., architect, founder of Curtis and Davis Architects and Engineers.

- Jefferson Davis was buried at Metairie Cemetery, but his remains were later moved to Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia.

- Dorothy Dell, film actress of the 1930s

- Dorothy Dix, advice columnist

- Charles E. Dunbar, New Orleans attorney and civil service reformer

- Charles E. Fenner, founder of brokerage house that became part of Merrill Lynch, Pearce, Fenner, & Smith

- Joachim O. Fernández, U.S. Representative from Louisiana's 1st congressional district from 1931 to 1941

- Ruth U. Fertel, founder of Ruth's Chris Steak House

- Benjamin Flanders, Reconstruction-era state governor and New Orleans mayor

- Jim Garrison, New Orleans District Attorney

- Edward James Gay III, U.S. Senator

- Michael Hahn, Speaker of the Louisiana House of Representatives and Governor of Louisiana

- William W. Heard, Governor of Louisiana from 1900–1904

- William G. Helis, Sr., American oilman, racehorse/owner breeder

- Andrew Higgins, inventor of the "Higgins Boat"

- Al Hirt, jazz trumpeter

- Ken Hollis, state senator from Jefferson Parish

- John Bell Hood, Confederate General

- Chapman H. Hyams, stockbroker, businessman and philanthropist

- John E. Jackson, Sr., New Orleans lawyer and state Republican chairman from 1929 to 1934

- Grace King, author

- Richard W. Leche, Governor of Louisiana

- Harry Lee, Sheriff of Jefferson Parish, Louisiana

- Samuel D. McEnery, Governor of Louisiana

- Louis H. Marrero, Jefferson Parish Police Juror & President, Jefferson Parish Sheriff, Senator, Lafourche Basin Levee Board

- John Albert Morris, the "Lottery King"

- deLesseps Story "Chep" Morrison, Sr., Mayor of New Orleans

- deLesseps Story "Toni" Morrison, Jr., state legislator from Orleans Parish

- Isidore Newman, New Orleans philanthropist and founder of the Maison Blanche department store chain and the regarded Isidore Newman School

- Elwyn Nicholson, state senator from 1972 to 1988, grocery store owner

- Margaret Norvell, lighthouse keeper and namesake of the coastguard cutter USCGC Margaret Norvell

- Alton Ochsner, surgeon, co-founder of Ochsner Clinic (now Ochsner Health System)

- Lionel Ott, member of the Louisiana State Senate from 1940 to 1945 and the last New Orleans finance commissioner from 1946 to 1954

- Mel Ott, Hall of Fame Major League Baseball Player

- Benjamin M. Palmer, pastor of First Presbyterian Church of New Orleans (1856–1902)

- John M. Parker, governor of Louisiana

- P. B. S. Pinchback, first African American Governor of Louisiana 1872-1873

- Louis Prima, bandleader

- Stan Rice, poet

- John Leonard Riddell, melter and refiner of Mint 1839–1848, Postmaster 1859–1862, inventor of the binocular microscope

- John G. Schwegmann, supermarket pioneer and member of both houses of the Louisiana State Legislature

- James Z. Spearing, U.S. representative, 1924–1931, from Louisiana's 2nd congressional district

- Edgar B. Stern, businessman and civic leader

- Edith Rosenwald Stern, philanthropist

- Norman Treigle, opera star

- Helen Turner, painter

- Cora Witherspoon, stage and screen character actress

See also

References

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ Linden, Blanche M.G. (2007). Silent City on a Hill: Picturesque Landscapes of Memory and Boston's Mount Auburn Cemetery. Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 295. ISBN 978-1-55849-571-5. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- ^ Snyder, Laurie. Cities of the Dead: Metairie Cemetery (New Orleans, Louisiana), in The Contemplative Traveler, November 25, 2016.

- ^ Metairie Cemetery, The Contemplative Traveler.

- ^ "Badger, Algernon Sidney". Louisiana Historical Association, A Dictionary of Louisiana Biography. Archived from the original on October 13, 2010. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- ^ Tom Benson's final resting place: Large, ornate tomb stands out in Metairie Cemetery

- ^ "Clarke, Lewis Strong". Louisiana Historical Association, A Dictionary of Louisiana Biography (lahistory.com). Archived from the original on February 25, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2010.