Sigurd stones

The Sigurd stones form a group of seven or eight runestones and one picture stone that depict imagery from the legend of Sigurd the dragon slayer. They were made during the Viking Age and they constitute the earliest Norse representations of the matter of the Nibelungenlied and the Sigurd legends in the Poetic Edda, the Prose Edda and the Völsunga saga.

In parts of Great Britain under Norse culture, the figure of Sigurd sucking the dragon's blood from his thumb appears on several carved stones, at Ripon and Kirby Hill, North Yorkshire, at York and at Halton, Lancashire.[1] Carved slates from the Isle of Man, broadly dated c. 950–1000, include several pieces interpreted as showing episodes from the Sigurd story.[2]

Uppland

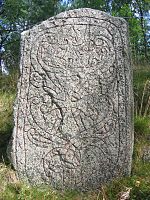

U 1163

This runestone is in runestone style Pr2. It was found in Drävle, but in 1878 it was moved to the courtyard of the manor house Göksbo in the vicinity where it is presently raised. It has an image of Sigurd who thrusts his sword through the serpent, and the dwarf Andvari, as well as the Valkyrie Sigrdrífa who gives Sigurd a drinking horn.

The runestone has a stylized Christian cross, as do a number of the Sigurd stones. Sigurd runestones with crosses are taken as evidence of the acceptance and use of legends from the Volsung saga by Christianity during the transition period from Norse paganism.[3] Other Sigurd stones with crosses in their designs include U 1175, Sö 327, Gs 2, and Gs 9.[3]

Latin transliteration:

- uiþbiurn × ok : karlunkr : ok × erinker : ok × nas(i) × litu × risa × stii × þina × eftir × eriibiun × f[aþu]r × sii × snelan

Old Norse transcription:

- Viðbiorn ok Karlungʀ ok Æringæiʀʀ/Æringærðr ok Nasi/Næsi letu ræisa stæin þenna æftiʀ Ærinbiorn, faður sinn sniallan.

English translation:

- "Viðbjôrn and Karlungr and Eringeirr/Eringerðr and Nasi/Nesi had this stone raised in memory of Erinbjôrn, their able father."

U 1175

This runestone is classified as being carved in runestone style Pr2 and it is located in Stora Ramsjö, which is just southeast of Morgongåva. It belongs to the category of nonsensical runestones that do not contain any runes, only runelike signs surrounding a design with a cross. The inscription has the same motifs and ornamentation as U 1163 and may be a copy of that runestone.[4]

Latin transliteration:

- ...

Old Norse transcription:

- ...

English translation:

- "..."

Södermanland

Sö 40, the Västerljung runestone

This runestone is located on the cemetery of the church of Västerljung, but it was originally found in 1959 in the foundation of the southwest corner of the church tower.[5] The stone is 2.95 meters in height and is carved on three sides. One side has the runic text within a serpent band with the head and tail of the serpent bound at the bottom. The inscription is classified as being carved in runestone style Pr2 and the text states that it was made by the runemaster Skamhals. Another runestone, Sö 323, is signed by a Skamhals, but that is believed to be a different person with the same name. The other two sides contain images, with one interpreted as depicting Gunnar playing the harp in the snake pit.

Of the names in the inscription, Geirmarr means "spear-steed"[6] and Skammhals is a nickname meaning "small neck."[7]

Latin transliteration:

- haunefʀ + raisti * at * kaiʀmar * faþur * sin + haa * iʀ intaþr * o * þiusti * skamals * hiak * runaʀ þaʀsi +

Old Norse transcription:

- Honæfʀ ræisti at Gæiʀmar, faður sinn. Hann eʀ ændaðr a Þiusti. Skammhals hiogg runaʀ þaʀsi.

English translation:

- "Hónefr raised (the stone) in memory of Geirmarr, his father. He met his end in Þjústr. Skammhals cut these runes."

Sö 101, the Ramsund carving

The Ramsund carving is not quite a runestone as it is not carved into a stone, but into a flat rock close to Ramsund, Eskilstuna Municipality, Södermanland, Sweden. It is believed to have been carved around the year 1030.[8] It is generally considered an important piece of Norse art in runestone style Pr1.

The Ramsund carving in Sweden depicts

- how Sigurd is sitting naked in front of the fire preparing the dragon heart, from Fafnir, for his foster-father Regin, who is Fafnir's brother. The heart is not finished yet, and when Sigurd touches it, he burns himself and sticks his finger into his mouth. As he has tasted dragon blood, he starts to understand the birds' song.

- The birds say that Regin will not keep his promise of reconciliation and will try to kill Sigurd, which causes Sigurd to cut off Regin's head.

- Regin is dead beside his own head, his smithing tools with which he reforged Sigurd's sword Gram are scattered around him, and

- Sigurd's horse Grani is laden with the dragon's treasure.

- is the previous event when Sigurd killed Fafnir, and

- shows Ótr from the saga's beginning.

The runic text is ambiguous, but one interpretation of the persons mentioned in the inscription, based on inscriptions on other runestones found nearby, is that Sigriþr (a woman) was the wife of Sigröd who has died. Holmgeirr is her father in law. Alrikr, son of Sigriþr, erected another stone for his father, named Spjut, so while Alrikr is the son of Sigriþr, he was not the son of Sigruþr. Alternatively, Holmgeirr is Sigriþr's second husband and Sigröd (but not Alrikr) is their son.

The inspiration for using the legend of Sigurd for the pictorial decoration was probably the close similarity of the names Sigurd (Sigurðr in Old Norse) and Sigröd.[9]

It is raised by the same aristocratic family as the Bro Runestone and the Kjula Runestone. The reference to bridge-building in the runic text is fairly common in rune stones during this time period. Some are Christian references related to passing the bridge into the afterlife. At this time, the Catholic Church sponsored the building of roads and bridges through the use of indulgences in return for intercession for the soul.[10] There are many examples of these bridge stones dated from the eleventh century, including runic inscriptions U 489 and U 617.[10]

Latin transliteration:

- siriþr : kiarþi : bur : þosi : muþiʀ : alriks : tutiʀ : urms : fur * salu : hulmkirs : faþur : sukruþar buata * sis *

Old Norse transcription:

- Sigriðr gærði bro þasi, moðiʀ Alriks, dottiʀ Orms, for salu Holmgæiʀs, faður Sigrøðaʀ, boanda sins.

English translation:

- "Sigríðr, Alríkr's mother, Ormr's daughter, made this bridge for the soul of Holmgeirr, father of Sigrøðr, her husbandman."

Sö 327, the Gök inscription

This inscription, located at Gök, which is about 5 kilometers west of Strängnäs, is on a boulder and is classified as being carved in runestone style Pr1-Pr2. The inscription, which has a width of 2.5 meters and a height of 1.65 meters, consists of runic text on two serpents that surround much of the Sigurd imagery. The inscription dates from the same time as the Ramsund carving and it uses the same imagery, but a Christian cross has been added and the images are combined in a way that completely distorts the internal logic of events.[11] Some have claimed that the runemaster either did not understand the underlying myth, or consciously distorted its representation.[11] Whatever the reason may have been, the Gök stone illustrates how the pagan heroic mythos was going towards its dissolution during the Christianization of Scandinavia.[11] However, the main figures from the story are represented in order when read from the right to the left.[12] Sigurd is shown below the lower serpent, stabbing up at it with his sword. Other images include a tree, the horse Grani, a bird, the head of Regin and a headless body, the roasting of the dragon heart, and Ótr.[12]

This inscription has never been satisfactorily transcribed nor translated.[12]

Latin transliteration:

- ... (i)uraʀi : kaum : isaio : raisti : stai : ain : þansi : at : : þuaʀ : fauþr : sloþn : kbrat : sin faþu... ul(i) * hano : msi +

Old Norse transcription:

- ...

English translation:

- "..."

Gästrikland

Gs 2

This sandstone runestone is classified as being carved in runestone style Pr2 and was rediscovered in 1974 outside of the wall of the church of Österfärnebo. It is not listed as a Sigurd runestone by the Rundata project, and only the bottom part of it remains. The inscription is reconstructed based upon a drawing made during a runestone survey in 1690 by Ulf Christoffersson.[13] The inscription originally included several figures from the Sigurd story, including a bird, Ótr with the ring, and a horse.[13]

The personal name Þorgeirr in the runic text means "Thor's spear."[14]

Latin transliteration:

- [ily]iki : ok : f[uluiki × ok : þurkair ... ...- × sin × snilan] : kuþ ilubi on(t)[a]

Old Norse transcription:

- Illugi ok Fullugi ok Þorgæiʀʀ ... ... sinn sniallan. Guð hialpi anda.

English translation:

- "Illugi and Fullugi and Þorgeirr ... their able ... May God help [his] spirit."

Gs 9

This runestone is found at the church of Årsunda and was documented during a survey in 1690.[15] It shows a man running at the top of the runestone, which by comparison with U 1163 from Drävle can be identified as Sigurd.[15] A second figure holds a ring in his hand. A cross is in the center of the design. Similar to the Sigurd stones U 1163, U 1175, Sö 327, and Gs 2, this combination of a cross and the Sigurd figure is taken as evidence of the acceptance and use by Christianity of legends from the Volsung Saga during the transition period from paganism.[3] The runic text, which is reconstructed from the 1690 drawing, uses a bind rune which combines the e- and l-runes in the name of the mother, Guðelfr.[16]

Latin transliteration:

- (i)nu-r : sun : r[u]þ[u](r) at × [uili](t)... ...[Ris:]t eftir : þurker : bruþu[r : sin : ok : kyþe=lfi : muþur : sina : uk] : eft[i]ʀ : [a]sbiorn : o[k : o]ifuþ

Old Norse transcription:

- Anun[d]r(?), sunn <ruþur>(?) at <uilit...> ... æftiʀ Þorgæiʀ, broður sinn, ok Guðælfi, moður sina ok æftiʀ Asbiorn ok <oifuþ>.

English translation:

- "Ônundr(?), <ruþur>'s son, in memory of <uilit>... ... in memory of Þorgeirr, his brother and Guðelfr, his mother, and in memory of Ásbjôrn and <oifuþ>"

Gs 19

This runestone which is tentatively categorized as style Pr2 is located at the church of Ockelbo. The original runestone was found in a foundation wall of the church in 1795 and removed and stored in the church in 1830. The runestone was destroyed together with the church in a fire in 1904. The present runestone is a copy made in 1932 after drawings and it is raised outside the church. The runestone has several illustrations including matter from the Sigurd legends. One shows two men playing Hnefatafl, a form of the boardgame called tofl.[17]

The name Svarthôfði in the inscription translates as "black head"[18] and was often used as a nickname.[19]

Latin transliteration:

- [blesa × lit × raisa × stain×kumbl × þesa × fa(i)(k)(r)(n) × ef(t)ir × sun sin × suar×aufþa × fr(i)þelfr × u-r × muþir × ons × siionum × kan : inuart : þisa × bhum : arn : (i)omuan sun : (m)(i)e(k)]

Old Norse transcription:

- Blæsa let ræisa stæinkumbl þessa fagru æftiʀ sun sinn Svarthaufða. Friðælfʀ v[a]ʀ moðiʀ hans <siionum> <kan> <inuart> <þisa> <bhum> <arn> <iomuan> sun <miek>.

English translation:

- "Blesa had these fair stone-monuments raised in memory of his son Svarthôfði. Friðelfr was his mother. ... "

Bohuslän

Bo NIYR;3

This baptismal font from c. 1100 is made in slate. It was discovered in pieces on the cemetery of Norum in 1847. On one side it shows Gunnar apparently resting in the snake pit surrounded by four snakes and with a harp at his feet.[20] Gunnar in the snake pit was used as a Biblical typology similar to that of Daniel in the lion den in representing Christ rising unharmed from hell.[21] Above the snake pit panel, there is a runic inscription. The inscription ends with five identical bind runes of which the last two are mirrored. The meaning of these five bind runes is not understood.

The font is currently at the Swedish Museum of National Antiquities.

- svæn : kærðe <m>

Old Norse transcription:

- Sveinn gerði m[ik](?).

English translation:

- "Sveinn made me(?)."

Gotland

Hunninge picture stone

The Hunninge picture stone was found on Gotland and it illustrates imagery from the tradition of the Nibelungenliend. On the top of the stone, there is a man on a horse with a dog meeting a woman and two men fighting near a dead man who is holding a ring.[3] This could represent Sigurd and Brynhild, Sigurd and Gunnar fighting, and Sigurd's death.[3] Alternatively, the man carrying a ring could be the messenger Knéfrøðr. On the bottom left, the scene depicts a woman watching the snake pit where Gunnar is lying, and at the bottom three men who possibly could be Gunnar and Hogli attacking Atli.[3]

The Hunninge picture stone is currently on display at the Gotland Museum in Visby.

See also

Notes

- ^ All noted by Richard Hall, Viking Age Archaeology 1995:40.

- ^ Hall 1995:40.

- ^ a b c d e f Staecker 2006:365-367.

- ^ Fuglesang 1980:182.

- ^ Jannson 1959:263-266.

- ^ Cleasby & Vigfússon 1878:196, 413.

- ^ Cleasby & Vigfússon 1878:537.

- ^ Düwel 1988:133.

- ^ Brate 1922:126; and Sawyer 2000:113.

- ^ a b Gräslund 2003:490-492.

- ^ a b c Lönnroth & Delblanc 1993:49.

- ^ a b c Liepe 1989:4-10

- ^ a b Schück 1932:257-265.

- ^ Cleasby & Vigfússon 1878:196.

- ^ a b Schück 1932:258-259, 263.

- ^ MacLeod 2002:37.

- ^ Helmfrid 2005:12.

- ^ Blackwell 1906:607.

- ^ Cleasby & Vigfússon 1878:607.

- ^ Du Chaillu 1882:358.

- ^ Düwel 1988:147.

References

- Blackwell, I. A. (transl.) (1906). The Elder Eddas of Saemund Sigfusson. Norreona Society.

- Brate, Erik. (1922). Sveriges Runinskrifter. Victor Petersons Bokindustriaktiebolag.

- Cleasby, Richard; Vigfússon, Guðbrandur (1878). An Icelandic-English Dictionary. Clarendon Press.

- Du Chaillu, Paul Belloni (1882). The Land of the Midnight Sun: Summer and Winter Journeys Through Sweden, Norway, Lapland, and Northern Finland. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Düwel, Klaus (1988). "On the Sigurd Representations in Great Britain and Scandinavia". In Jazayery, Mohammad Ali; Winter, Werner (eds.). Languages and Cultures: Studies in Honor of Edgar C. Polomé. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 133–156. ISBN 3-11-010204-8.

- Fuglesang, Signe Horn (1980). Some Aspects of the Ringerike Style: A Phase of 11th Century Scandinavian Art. Odense University Press. ISBN 87-7492-183-5.

- Gräslund, Anne-Sofie (2003). "The Role of Scandinavian Women in Christianisation: The Neglected Evidence". In Carver, Martin (ed.). The Cross Goes North: Processes of Conversion in Northern Europe, AD 300-1300. Boydell Press. pp. 483–496. ISBN 1-903153-11-5.

- Hammer, K. V. (1917). "Sigurdsristningar" in Nordisk familjebok 25, p. 461-462.

- Helmfrid, Sten (2005). "Hnefatafl: The Strategic Board Game of the Vikings" (PDF). Retrieved 3 August 2010.

- Jansson, Sven B. F. (1959). "Rapport om Östgötska och Småländska Runfynd" (PDF). Fornvännen. 54. Swedish National Heritage Board: 241–267. ISSN 1404-9430. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- Liepe, Lena (1989). "Sigurdssagan i Bild" (PDF). Fornvännen. 84. Swedish National Heritage Board: 1–11. ISSN 1404-9430. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- Lönnroth, L. & Delblanc, S. (1993). Den Svenska Litteraturen. 1, Från Forntid till Frihetstid : 800-1718. Stockholm : Bonnier Alba. ISBN 91-34-51408-2.

- MacLeod, Mindy (2002). Bind-Runes: An Investigation of Ligatures in Runic Epigraphy. Uppsala Universitet. ISBN 91-506-1534-3.

- Sawyer, Birgit (2000). The Viking-Age Rune-Stones: Custom and Commemoration in Early Medieval Scandinavia. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820643-7.

- Schück, Henrik (1932). "Två Sigurdsristningar" (PDF). Fornvännen. 27. Swedish National Heritage Board: 257–265. ISSN 1404-9430. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- Staecker, Jörn (2006). "Heroes, Kings, and Gods". In Andrén, Anders; Jennbert, Kristina; et al. (eds.). Old Norse Religion in Long-Term perspectives: Origins, Changes, and Interactions. Lund: Nordic Academic Press. pp. 363–368. ISBN 91-89116-81-X.

- An online article at the Foteviken Museum

- Project Samnordisk Runtextdatabas Svensk – Rundata