Pincer movement

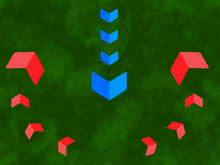

The pincer movement, or double envelopment, is a military maneuver in which forces simultaneously attack both flanks (sides) of an enemy formation.

The pincer movement typically occurs when opposing forces advance towards the center of an army that responds by moving its outside forces to the enemy's flanks to surround it. At the same time, a second layer of pincers may attack the more distant flanks to keep reinforcements from the target units.

Description

A full pincer movement leads to the attacking army facing the enemy in front, on both flanks, and in the rear. If attacking pincers link up in the enemy's rear, the enemy is encircled. Such battles often end in surrendering or destroying the enemy force, but the encircled force can try to break out. They can attack the encirclement from the inside to escape, or a friendly external force can attack from the outside to open an escape route.

History

Sun Tzu, in The Art of War (traditionally dated to the 6th century BC), speculated on the maneuver but advised against trying it for fear that an army would likely run first before the move could be completed. He argued that it was best to allow the enemy a path to escape (or at least the appearance of one), as the target army would fight with more ferocity when surrounded. Still, it would lose formation and be more vulnerable to destruction if shown an avenue of escape.

The maneuver may have first been used at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC. The historian Herodotus describes how the Athenian general Miltiades deployed 900 Plataean and 10,000 Athenian hoplites in a U-formation with the wings manned much more deeply than the centre. His enemy outnumbered him heavily, and Miltiades chose to match the breadth of the Persian battle line by thinning out the center of his forces while reinforcing the wings. In the course of the battle, the weaker central formations retreated, allowing the wings to converge behind the Persian battle line and drive the more numerous but lightly armed Persians to retreat in panic.

The tactic was used by Alexander the Great at the Battle of the Hydaspes in 326 BC. Launching his attack at the Indian left flank, the Indian king Porus reacted by sending the cavalry on the right of his formation around in support. Alexander had positioned two cavalry units on the left of his formation, hidden from view, under the command of Coenus and Demitrius. The units were then able to follow Porus's cavalry around, trapping them in a classic pincer movement. That tactically-astute move from Alexander was key in ensuring what many regard as his last great victory.

The most famous example of its use was at the Battle of Cannae in 216 BC, when Hannibal executed the maneuver against the Romans. Military historians view it as one of the greatest battlefield maneuvers in history and cite it as the first successful use of the pincer movement that was recorded in detail,[1] by the Greek historian Polybius.

It was also later used effectively by Khalid ibn al-Walid at the Battle of Walaja in 633, by Alp Arslan at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 (under the name crescent tactic), at Battle of Mohács by Süleyman the Magnificent in 1526 and by Field Marshal Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld at the Battle of Fraustadt in 1706.

Daniel Morgan used it effectively at the Battle of Cowpens in 1781 in South Carolina. Many consider Morgan's cunning plan at Cowpens the tactical masterpiece of the American War of Independence.

Zulu impis used a version of the manoeuvre that they called the buffalo horn formation.

Genghis Khan used a rudimentary form known colloquially as the horns tactic. Two enveloping flanks of horsemen surrounded the enemy, but they usually remained unjoined, leaving the enemy an escape route to the rear, as described above. It was key to many of Genghis's early victories over other Mongolian tribes.

Even in the horse-and-musket era, the maneuver was used across many military cultures. A classic double envelopment was deployed by the Iranian conqueror Nader Shah at the Battle of Kirkuk (1733) against the Ottomans; the Persian army, under Nader, flanked the Ottomans on both ends of their line and encircled their centre despite being numerically at a disadvantage. In another battle at Kars in 1745, Nader routed the Ottoman army and subsequently encircled their encampment. The Ottoman army soon after collapsed under the pressure of the encirclement. Also during the famous Battle of Karnal in 1739, Nader drew out the Mughal army which outnumbered his own force by over six to one, and managed to encircle and utterly decimate a significant contingent of the Mughals in an ambush around Kunjpura village.

The manoeuvre was used in the blitzkrieg of the armed forces of Nazi Germany during World War II. Then it developed into a complex, multidisciplinary endeavor that involved fast movement by mechanized armor, artillery barrages, air force bombardment, and effective radio communications, with the primary objective of destroying enemy command and control chains, undermining enemy troop morale and disrupting supply lines. During the Battle of Kiev (1941) the Axis forces managed to encircle the largest number of soldiers in the history of warfare. Well over half-a-million Soviet soldiers were taken prisoner by the end of the operation.

Examples

- Battle of Xuge (707 BC)

- Battle of Marathon (490 BC)

- Battle of the Hydaspes (325 BC)

- Battle of the Bagradas (255 BC)

- Battle of the Trebia (218 BC)

- Battle of Cannae (216 BC)

- Battle of Herdonia (212 BC)

- Battle of Baecula (208 BC)

- Battle of Ilipa (206 BC)

- Battle of the Great Plains (203 BC)

- Battle of Panium (200 BC)

- Battle of Italica (75 BC)

- Battle of the Abas (65 BC)

- Battle of Faventia (542)

- Battle of Taginae (552)

- Battle of the Volturnus (554)

- Battle of Walaja (633)

- Battle of Toulouse (721)

- Battle of Andernach (876)

- Battle on the Raxa (955)

- Battle of Manzikert (1071)

- Battle of Ager Sanguinis (1119)

- Battle of Hattin (1187)

- Battle of Indus (1221)

- Battle of Mohi (1241)

- Battle of Bapheus (1302)

- Battle of Dupplin Moor (1332)

- Battle of Roosebeke (1382)

- Battle of Othée (1408)

- Battle of Agincourt (1415)

- Battle of Dabul (1508)

- Battle of Mohács (1526)

- Battle of Kawanakajima (1561)

- Battle of Alcácer Quibir (1578)

- Battle of Hansan Island (1592)

- Battle of Urmia (1604)

- Battle of Wittstock (1636)

- Battle of Kempen (1642)

- Battle of Rocroi (1643)

- Battle of Lens (1648)

- Battle of Fleurus (1690)

- Battle of Zenta (1697)

- Battle of Fraustadt (1706)

- Battle of Kirkuk (1733)

- Battle of Karnal (1739)

- Battle of Kars (1745)

- Battle of Maxen (1759)

- Battle of Trenton (1776)

- Battle of Bennington (1777)

- Battle of Cowpens (1781)

- Battle of Castiglione (1796)

- Ulm Campaign (1805)

- Battle of Jena–Auerstedt (1806)

- Battle of Castellón (1809)

- Battle of Medellín (1809)

- Battle of Ocaña (1809)

- Battle of San Lorenzo (1813)

- Battle of Dresden (1813)

- Battle of Gqokli Hill (1818)

- Battle of Aliwal (1846)

- Second Bull Run (1862)

- Battle of Corydon (1863)

- Battle of Brice's Crossroads (1864)

- Battle of Königgrätz (1866)

- Battle of Sedan (1870)

- Battle of Isandlwana (1879)

- Battle of Rossignol (1914)

- Battle of Tannenberg (1914)

- Second Battle of the Masurian Lakes (1915)

- Siege of Kut (1915–1916)

- Battle of Kilosa (1916)

- Battle of the Argeș (1916)

- Battle of Magdhaba (1916)

- Battle of Rafa (1917)

- Battle of Beersheba (1917)

- Battle of Dumlupınar (1922)

- Battle of Alfambra (1938)

- Battle of Merida pocket (1938)

- Battle of Khalkhin Gol (1939)

- Battle of the Bzura (1939)

- Siege of Warsaw (1939)

- Battle of France (1940)

- Defense of Brest Fortress (1941)

- Battle of Białystok–Minsk (1941)

- Battle of Smolensk (1941)

- Battle of Uman (1941)

- Battle of Porlampi (1941)

- Battle of Kiev (1941)

- Battle of the Sea of Azov (1941)

- Battle of Petrikowka (1941)

- Battle of Moscow (1941–1942)

- Battle of the Kerch Peninsula (1942)

- Second Battle of Kharkov (1942)

- Battle of Mersa Matruh (1942)

- Battle of Kalach (1942)

- Sinyavino Offensive (1942)

- Operation Uranus (1942)

- Operation Little Saturn (1942–1943)

- Third Battle of Kharkov (1943)

- Operation Postern (1943)

- Operation Bagration (1944)

- Battle of Ilomantsi (1944)

- Battle of Radzymin (1944)

- Battle of Falaise (1944)

- Second Jassy–Kishinev Offensive (1944)

- Battle of St. Vith (1944)

- Siege of Budapest (1944–1945)

- Heiligenbeil Pocket (1945)

- Battle of Königsberg (1945)

- Battle of Kolberg (1945)

- Ruhr Pocket (1945)

- Battle of Berlin (1945)

- Battle of Halbe (1945)

- Manchurian Strategic Offensive Operation (1945)

- Battle of Jinan (1948)

- Huaihai Campaign (1948–1949)

- Battle of Chochiwon (1950)

- Operation Beit ol-Moqaddas (1982)

- Battle of Aanandapuram (2009)

- Second Battle of Tikrit (2015)

- Battle of al-Bab (2016)

- Battle of Afrin (2018)

See also

References

- ^ "Appendix C" (PDF). The complete book of military science, abridged. Archived from the original (PDF file —viewed as cached HTML—) on 2002-01-13. Retrieved March 25, 2006.

Further reading

- U.S. Army training manual diagram of different modes of attack, including double envelopment.

- GlobalSecurity.org essay with a section on envelopments.

- Academic paper on military diagramming with diagram of a double envelopment.

- Map of Georgy Zhukov's double envelopment at the battle of Stalingrad.