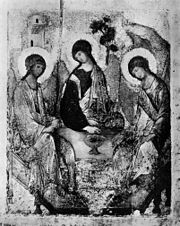

Trinity (Andrei Rublev)

| The Trinity | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Andrei Rublev |

| Year | 1411 or 1425–27 |

| Medium | Tempera |

| Dimensions | 142 cm × 114 cm (56 in × 45 in) |

| Location | Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow |

The Trinity (Russian: Троица, romanized: Troitsa, also called The Hospitality of Abraham) is an icon created by Russian painter Andrei Rublev in the 15th century.[1] It is his most famous work[2] and the most famous of all Russian icons,[3] and it is regarded as one of the highest achievements of Russian art.[4][5] Scholars believe that it is one of only two works of art (the other being the Dormition Cathedral frescoes in Vladimir) that can be attributed to Rublev with any sort of certainty.[1]

The Trinity depicts the three angels who visited Abraham at the Oak of Mamre (Genesis 18:1–8), but the painting is full of symbolism and is interpreted as an icon of the Holy Trinity. At the time of Rublev, the Holy Trinity was the embodiment of spiritual unity, peace, harmony, mutual love and humility.[6]

The icon was commissioned to honour Saint Sergius of Radonezh of the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius, near Moscow, now in the town of Sergiyev Posad. Little is known about The Trinity's history, and art historians make suggestions based on only the few known facts.[7] Even the authorship of Rublev has been questioned. Various authors suggest different dates, such as 1408–1425, 1422–1423 or 1420–1427. The official version states 1411 or 1425–27. The Trinity is currently held in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

Description

The Trinity was painted on a vertically aligned board. It depicts three angels sitting at a table. On the table, there is a cup containing the head of a calf. In the background, Rublev painted a house (supposedly Abraham's house), a tree (the Oak of Mamre), and a mountain (Mount Moriah). The figures of angels are arranged so that the lines of their bodies form a full circle. The middle angel and the one on the left bless the cup with a hand gesture.[8] There is no action or movement in the painting. The figures gaze into eternity in the state of motionless contemplation. There are sealed traces of nails from the icon's riza (metal protective cover) on the margins, halos and around the cup.

Iconography

The icon is based on a story from the Book of Genesis called Abraham and Sarah's Hospitality or The Hospitality of Abraham (§18). It says that the biblical Patriarch Abraham 'was sitting at the door of his tent in the heat of the day' by the Oak of Mamre and saw three men standing in front of him, who in the next chapter were revealed as angels. 'When he saw them, Abraham ran from the tent door to meet them and bowed himself to the earth.' Abraham ordered a servant-boy to prepare a choice calf, and set curds, milk and the calf before them, waiting on them, under a tree, as they ate (Genesis 18:1–8). One of the angels told Abraham that Sarah would soon give birth to a son.

The subject of The Trinity received various interpretations at different time periods, but by the 19th–20th century the consensus among scholars was the following: the three angels who visited Abraham represented the Christian Trinity, "one God in three persons" – the Father, the Son (Jesus Christ), and the Holy Spirit.[9] Art critics believe that Andrei Rublev's icon was created in accordance with this concept. In his effort to uncover the doctrine of the Trinity, Rublev abandoned most of the traditional plot elements which were typically included in the paintings of the Abraham and Sarah's Hospitality story. He did not paint Abraham, Sarah, the scene of calf's slaughter, nor did he give any details on the meal. The angels were depicted as talking, not eating. "The gestures of angels, smooth and restrained, demonstrate the sublime nature of their conversation".[10] The silent communion of the three angels is the centre of the composition.

In Rublev's icon, the form that most clearly represents the idea of the consubstantiality of the Trinity's three hypostases is a circle. It is the foundation of the composition. At the same time, the angels are not inserted into the circle, but create it instead, thus our eyes can't stop at any of the three figures and rather dwell inside this limited space. The impactful center of the composition is the cup with the calf's head. It hints at the crucifixion sacrifice and serves as the reminder of the Eucharist (the left and the right angels' figures make a silhouette that resembles a cup). Around the cup, which is placed on the table, the silent dialogue of gestures takes place.[11]

The left angel symbolizes God the Father. He blesses the cup, yet his hand is painted in a distance, as if he passes the cup to the central angel. Viktor Lazarev suggests that the central angel represents Jesus Christ, who in turn blesses the cup as well and accepts it with a bow as if saying "My Father, if it is possible, may this cup be taken from me. Yet not as I will, but as you will". (Mt 26:39Template:Bibleverse with invalid book)[12] The nature of each of the three hypostases is revealed through their symbolic attributes, i.e. the house, the tree, and the mountain.[6] The starting point of the divine administration is the creative Will of God, therefore Rublev places the Abraham's house above the corresponding angel's head. The Oak of Mamre can be interpreted as the tree of life,[6] and it serves as a reminder of the Jesus's death on the cross and his subsequent resurrection, which opened the way to eternal life. The Oak is located in the centre, above the angel who symbolizes Jesus. Finally, the mountain is a symbol of the spiritual ascent, which mankind accomplishes with the help of the Holy Spirit.[10] The unity of the Trinity's three hypostases expresses unity and love between all things: "That they may all be one, just as you, Father, are in me, and I in you, that they also may be in us, so that the world may believe that you have sent me." (John 17:21Template:Bibleverse with invalid book)

The wings of two angels, the Father and the Son, interlap. The blue colour of the Son's robe symbolizes divinity, the brown colour represents earth, his humanity, and the gold speaks of kingship of God.[13] The wings of the Holy Spirit do not touch the Son's wings, they are imperceptibly divided by the Son's spear. The blue colour of the Holy Spirit's robe symbolizes divinity, the green colour represents new life.[14] The poses and the inclinations of the Holy Spirit and the Son's heads demonstrate their submission to the Father, yet their placement on the thrones at the same level symbolizes equality.[15]

The rizas

According to Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius records as of 1575, the icon was "covered with gold" at the order of Ivan the Terrible, i.e. a golden riza was commissioned by him and added to the icon. The golden riza was renewed in 1600 during the tsardom of Boris Godunov. A new riza copied that of Ivan the Terrible, while the original was moved to the new copy of The Trinity painted specifically for that purpose. In 1626 Michael I ordered golden tsatas with enamel and gemstones to be added to the riza. In the 18th century the gilded silver stamped angel attires were added.[16] Another copy of the riza was made in 1926–28. Both copies are now kept in the Trinity Lavra's Trinity Cathedral iconostasis.

Dating and provenance

The dating of The Trinity is uncertain. There is not much historical data on the subject, and even at the beginning of the 20th century historians did not dare to claim any facts and could only make guesses and assumptions.[10] The icon was first mentioned in 1551 in The Book of One Hundred Chapters, the collection of Church laws and regulations made by the Stoglavy Synod. Among other things, The Book stated the Synod's decisions that had been made about the iconography of the Holy Trinity, in particular the details that were considered canonically necessary for such icons, such as crosses and halos.

... the icon painter [has] to paint icons from the ancient examples, as did the Greek icon painters, and as did Ondrei [sic] Rublev and other predecessors...(Template:Lang-ru)

It is evident from this text that participants of the Stoglavy Synod were aware of some Trinity icon which had been created by Andrei Rublev and which, in their opinion, corresponded with every church canon and could be taken as a model example.[17][18]

The next known source that mentions The Trinity is The Legend of the Saint Icon Painters (Template:Lang-ru) compiled at the end of 17th century—the beginning of the 18th century. It contains a lot of semi-legendary stories, including a mention that Nikon of Radonezh, the pupil of Sergius of Radonezh, asked Andrei Rublev "to paint the image of the Holy Trinity to honour the father Sergius".[19] Unfortunately this late source is viewed by most historians as unreliable. However, due to lack of other facts, this version of The Trinity's making is generally accepted.[2] The question of when the conversation with Nikon occurred remains open.

The original wooden Trinity Church, located on the territory of the Trinity Lavra, burned down in 1411, and Nikon of Radonezh decided to build a new church. By 1425 the stone Trinity Cathedral was erected, which still stands today. It is believed that Nikon, who became the prior after the death of Sergius of Radonezh, sensed his forthcoming death, and invited Andrei Rublev and Daniel Chorny to finish the decoration of the recently built cathedral. The icon painters were supposed to make the frescos and create the many-tiered iconostasis.[20] But neither Life of St. Sergius, the hagiographical account of his life, nor Life of St. Nikon mention The Trinity icon, it is only written the decoration of the Cathedral in 1425–1427.

This dating is based on the dates of the construction of both churches. Nevertheless, art critics, taking into account the style of the icon, do not consider the matter resolved. Igor Grabar dated The Trinity 1408–1425, Yulia Lebedeva suggested 1422–1423, Valentina Antonova suggested 1420–1427. It is unknown if The Trinity was created during Rublev's peak of creativity in 1408—1420 or late in his life. Style analysis shows that it could have been created around 1408, because it is stylistically similar to his frescoes in the Dormition Cathedral (created roughly at the same time).[21] On the other hand, The Trinity demonstrates firmness and perfection which was unmatched even by the best of Trinity Cathedral's icons painted between 1425 and 1427.[22]

The Soviet historian Vladimir Plugin had a theory that the icon had nothing to do with Nikon of Radonezh, but was brought to the Trinity Lavra by Ivan the Terrible. He theorized that all previous scholars after the famous historian Alexander Gorsky made the wrong assumption that Ivan the Terrible only "covered with gold" the icon that had already been kept at the Trinity Lavra.[23] Plugin said that the icon was brought to the Lavra by Ivan himself, and that The Trinity had been created much earlier, probably 150 years prior to that date.[10] However, in 1998 Boris Kloss pointed out that the so-called Troitsk Story of the Siege of Kazan, written before June 1553,[24] contains a clear reference to the fact that Ivan the Terrible only "decorated" the existing icon for the Lavra.[25][26]

Authorship

Rublev was first called the author of a Trinity icon in the middle of the 16th-century text The Book of One Hundred Chapters. Scholars can be quite certain that by the mid-16th century, Rublev was considered to be the author of an icon with such name. The Russian ethnographer Ivan Snegiryov made a suggestion that The Trinity kept in the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius was in fact the icon of Rublev, who then was one of the few Russian icon painters known by name. The idea gained popularity among scholars and by 1905, it was predominate.[27] The Trinity is still generally accepted as his work.

Nevertheless, after cleaning of the icon art critics were so amazed by its beauty that some theories arose about it being created by an Italian painter. The first person to make the suggestion was Dmitry Rovinsky even before the cleaning, but his idea "was immediately extinguished by the note from metropolitan Philaret; and again, on the basis of the legend, the icon was attributed to Rublev. It continued to serve to those who studied this painter's style as one of his main works of art". Dmitry Aynalov,[28] Nikolai Sychyov and then Nikolay Punin all compared The Trinity to the works of Giotto and Duccio.[29] Viktor Lazarev compared it to the works of Piero della Francesca.[30] However, they most likely intended to point out the high quality of the painting because none of them claimed that it was created under the influence of the Italians. Viktor Lazarev sums it up: "In the light of recent analysis we can definitely state that Rublev was not familiar with the works of Italian art and therefore could not borrow anything from that. His main source was the Byzantine art of the Palaiologos era, in particular the paintings created in its capital, Constantinople. The elegance of his angels, the inclined heads motive, the rectangular shape of the meal were derived exactly from there".[8]

History

According to the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius archives, the icon was kept in the Trinity Cathedral since 1575. It took the main place (to the right of the royal doors) in the bottom tier of the iconostasis. It was one of the most revered icons in the monastery, attracting generous donations from the reigning monarchs (first Ivan the Terrible, then Boris Godunov and his family), but the main object of veneration in the monastery was Sergius of Radonezh's relics. Until the end of 1904, The Trinity was hidden from the eyes under the heavy golden riza, which left only the faces and the hands of the angels (the so-called "face image") open.

At the turn of the 19th and 20th century, Russian iconography was "discovered" by art historians as a form of art. Icons were taken out of the rizas that used to cover them almost completely except for faces and hands and then cleaned. The clearing was necessary because the icons were traditionally coated with a layer of drying oil. Under normal conditions, the drying oil fully darkened in 30–90 years. A new icon could be painted over the darkened layer. Usually, it had the same theme but the style was changed accordingly to the new aesthetic principles of that time. In some cases, the new painter kept the proportions and the composition of the original, but in other cases, the painter copied the theme but made adjustments to the proportions of the figures and the poses and changed other details. It was called the "icon renewal" (Template:Lang-ru).[31] The Trinity was under "renewal" four or five times.[32] The first renewal probably happened during the tsardom of Boris Godunov. The next was most likely finished by 1635, with the renewal of all monumental paintings and the iconostasis of the Trinity Lavra. Art historians attribute most of the damage of the layer of paint to that period. The damage done by pumice is especially visible on the angels' clothing and the background. The Trinity was further renewed in 1777 at the times of the Metropolitan Platon, when the whole iconostasis was remade. Vasily Guryanov stated that it was renewed two more times in 1835 and 1854: by the Palekh school painters and by the artist I. M. Malyshev, respectively.[32]

The 1904 cleaning

At the beginning of the 20th century many icons were cleaned one by one, and many of them turned out to be masterpieces. Eventually scholars became interested in The Trinity from the Trinity Lavra. Compared to other icons such as Theotokos of Vladimir or Our Lady of Kazan The Trinity was not particularly revered, because there was nothing special about it, it was not "miracle-working" or myrrh-streaming, and it didn't become a source for a large number of copies. However it had a certain reputation due to the fact that it was believed to be the very icon from The Book of One Hundred Chapters. As Andrei Rublev's name appeared in The Book as well, he was held in high regard among the Christian believers. A lot of different icons and frescoes were attributed to him, e.g. the frescoes in the Church of the Dormition in Gorodok. The cleaning of The Trinity could theoretically reveal a perfect example of his style and help with the examination of the other icons that were attributed to him on the basis of legends or common belief.[17]

Invited by the prior of the Trinity Lavra in the spring of 1904, Vasily Guryanov took the icon out from the iconostasis, removed the riza and then cleaned it from the "renewals" and the drying oil.[17][33] Ilya Ostroukhov recommended him for the job. He was helped by V. A. Tyulin and A. I. Izraztsov. After removing the riza, Guryanov did not find out Rublev's painting, but discovered the results of all the "renewals". Rublev's art was underneath them. He wrote: "When the golden riza was removed from this icon, we saw a perfectly painted icon. The background and the margins were coloured brown, golden inscription were new. All angels' clothes were repainted in a lilac tone and whitewashed not with paint, but with gold; the table, the mountain and the house were repainted… There were only faces left on which it was possible to evaluate that this icon was ancient, but even they were shaded by brown oil paint.".[34] As it became clear during another restoration in 1919, Guryanov didn't reach the original layer in some places. After Guryanov removed three upper layers, the last of which was painted in the Palekh school style, he revealed the original layer. Both the restorer and the eyewitnesses of the occasion were stunned. Instead of dark smoky tones of drying oil and brown-toned clothing that was typical for iconography of that time, they saw bright colours and transparent clothing that reminded them of the 14th century Italian frescos and icons.[17] Then he repainted the icon according to his own views on how it should look like. After that The Trinity was returned to the iconostasis.

Guryanov's effort was panned even by his contemporaries. In 1915 Nikolai Sychyov pointed out that his restoration actually hid the work of art from us. It had to be liquidated later. Y. Malkov summed up:

Only the painting's exposure in 1918 can be called "a restoration" in the modern scientific meaning of this word (and even that cannot be said without some reservations); all previous works on The Trinity were, in fact, only "renewals", including the "restoration" that took place in 1904—1905 under the guidance of V. P. Guryanov... No doubt, the restorers consciously tried to strengthen all the graphic and linear structure of the icon, with rough augmentation of the figures' contours, clothes, halos. There was even an obvious meddling in the inner sanctum, the "face image" area, where insufficiently cleaned remains of the author's.. lines...(which were already rather schematically reproduced by the latest renewals of the 16—19th centuries) were literally rumpled and absorbed by the rigid graphics of V. P. Guryanov and his assistants.[32]

The 1918 cleaning

As soon as the icon returned to the Trinity Cathedral's iconostasis, it darkened again very quickly. It was necessary to open it again. The Ancient Paintings Cleaning Committee of Russia took charge of the restoration in 1918. Yury Olsufyev was the leader of the team which also included Igor Grabar, Alexander Anisimov, Alexis Gritchenko, and the Works of Art Protection Committee under the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius, which included Yury Olsufyev himself, Pavel Florensky, Pavel Kapterev. Restoration work commenced on 28 November 28, 1918 and lasted until 2 January 2, 1919. It was carried out by I. Suslov, V. Tyulin, and G. Chirikov. All stages of the cleaning were recorded in detail in the Diary. Based on this records and Yury Olsufyev's personal observations, the summary of the works called Protocol No. 1 was created in 1925.[32] These documents are kept in the Tretyakov Gallery archives. Some details and lines were restored, others were found damaged beyond restoration.[32]

Problems with the safe-keeping of The Trinity stated in 1918–19 immediately after its cleaning. Twice a year, in spring and in autumn, humidity in the Trinity Cathedral increased and the icon was transferred to the so-called First Icon Depository. The continued changes in temperature and humidity affected its condition.

In the Tretyakov Gallery

Before the October Revolution The Trinity remained in the Trinity Cathedral, but after the Soviet government sent it to the recently founded Central National Restoration Workshop. On 20 April 1920 the Council of People's Commissars issued a decree called About the Conversion of the Historical and Artistic Valuables of the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius into a Museum (Template:Lang-ru). It handed the Lavra itself and all its collections over to the jurisdiction of the National Education Commissariat "for the purpose of democratization of artistic and historical buildings by transformation of said buildings and collections into museums". The Trinity ended up in the Zagorsk National Park & Museum of History and Arts. In 1929 the icon arrived to the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, while the copy made by Nikolai Baranov replaced the original in the iconostasis.

The icon is kept in Andrei Rublev's room of the Tretyakov Gallery. It has left the Gallery only twice. First it happened in 1941 during World War II evacuation. It was temporarily moved to the Novosibirsk Opera and Ballet Theatre in Novosibirsk. On 17 May 1945 The Trinity was returned to the Tretyakov Gallery. In May 2007 The Trinity was is taken out for the Europe-Russia-Europe exhibition, but a piece of the board was dislocated and had to be fixed and reinforced. Since 1997 the icon is moved every Pentecost from Andrei Rublev's room to the Tretyakov Gallery's church. It is placed under a special show-window with perfect temperature and humidity conditions. The first President of the Russian Federation Boris Yeltsin had an idea of handing the icon over back to the Church. However Valentin Yanin with an assistance of Yuri Melentyev, the Minister of Culture at that time, managed to meet with the President and made him change his mind. The matter concluded with a decree published in the Rossiyskaya Gazeta, The Trinity was declared a property of the Tretyakov Gallery forever.

In 2008 Levon Nersesyan, one of the Gallery staff members, revealed that Patriarch Alexy had requested the icon to be brought to the Lavra for the religious holiday in the summer of 2009.[35] Most scholars agreed that the climate inside the Cathedral is completely unsuitable for the icon keeping, that candles, frankincense and the transportation could destroy it. The only person who supported the move was the director of the Gallery. All the other staff, art critics and art historians were against it. The director was accused of committing a misfeasance.[1] Valentin Yanin said: "The Trinity is an outstanding work of art, a national patrimony, which should be available to people of all beliefs regardless of their religion. Outstanding works of art are supposed to be kept not inside churches for a narrow circle of parishioners to see, but in public museums."[1] The icon eventually stayed in the museum.

Conservation

The present condition of The Trinity differs from its original condition. Changes were made to it at least as early as 1600, and most probably even earlier. The condition closest to the original one that the restorers managed to achieve was after the restoration of 1918. That restoration revealed most of Rublev's original work, but numerous traces of the work of Guryanov and of other centuries were preserved. The present surface is a combination of layers created during various time periods. The icon is presently strengthened by shponkas, i. e. small dowels that are used specifically for icons.

Presently The Trinity is kept in a special glass cabinet in the museum under constant humidity and temperature conditions.

The Tretyakov Gallery reported the present condition as "stable".[1] There are persistent gaps between the ground and paint layers, especially in the margins. The primary problem is a vertical crack passing through the surface in the front, which a rupture between the first and second ground boards at an unknown time caused. Guryanov recorded the crack during his cleaning: a 1905 photograph depicts the crack as already present.

The crack became noticeable in 1931 and was partially fixed in the spring of 1931. At that time, the gap reached 2 mm at the top part of the icon and 1 mm on the face of the right angel. Yury Olsufyev attempted repair by moving the icon to a special room with artificially induced high humidity of circa 70%. The gap between the boards closed almost completely in 1–5 months. By the summer of 1931 the progress of narrowing the gap via exposure to the humidity ceased. It was then decided to strengthen the layer of gesso and the layer of paint with mastic, and fill the gap with it.[1]

The restorers could not be certain how different layers of paint of different times might have reacted to the slightest ambient changes. The slightest climatic change may still cause unpredictable damage. The committee of restorers of the Tretyakov Gallery deliberated at length on various suggestions of how to further strengthen the icon, and on 10 November 2008 the committee concluded that the present, stable condition of the icon is not to be interfered with in any circumstance.[1]

Copies

There are two consecrated copies of The Trinity. By the Orthodox church tradition, the consecrated copy of an icon and the original (also called the protograph) are completely interchangeable.[1]

- The Godunov's copy, commissioned by Boris Godunov in 1598–1600 for the purpose of moving the Ivan the Terrible riza to it. It was kept in the Trinity Cathedral of the Trinity Lavra of St. Sergius.

- The Baranov and Chirikov's copy, commissioned in 1926–28 for the International Icon Restoration Exhibition in 1929.[1] It replaced the original icon after it had been moved to the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

Both icons are now kept in the iconostasis of the Trinity Cathedral in Sergiyev Posad.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Стенограмма расширенного реставрационного совещания в Государственной Третьяковской Галерее по вопросу "Троицы" Рублева 17 ноября 2008 года (in Russian). Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- ^ a b "The Trinity by Andrei Rublev" (in Russian). Tretyakov Gallery. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- ^ Аверинцев, С. С. "Красота изначальная." Наше наследие 4 (1988): 25–26.

- ^ Дружкова, НАТАЛИЯ ИВАНОВНА. "современные визуально-коммуникационные средства в преподавании теории и истории изобразительного искусства [Электронный ресурс]." Педагогика искусства: электрон. науч. журн. Учреждения Рос. академии образования «Институт художественного образования 1 (2014).

- ^ "Explanation of Andrei Rublev's Icon". St John's Anglican Church. Archived from the original on 2008-07-19. Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- ^ a b c Е.В.Гутов, ed. (2011-04-27). "1". Пасхальные чтения: Тезисы докладов студенческой научно-теоретической конференции (PDF) (in Russian). Нижневартовск: Издательство Нижневартовского государственного гуманитарного университета. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9785899888670.

- ^ "Holy Trinity of Andrei Rublev" (in Russian). AndreiRublev.ru. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ^ a b Лазарев В. Н. "Русская иконопись от истоков до начала XVI века. Глава VI. Московская школа. VI.15. "Троица" Андрея Рублева". Archived from the original on 2012-02-26. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ^ "Rublev's Icon of the Trinity". wellsprings.org.uk. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ^ a b c d ""Святая Троица" Андрея Рублева. Описание, история иконы". Archived from the original on 2011-08-25. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ^ Аудиоэкскурсия по Третьяковской Галерее // «Троица» Рублева. Текст Л. Нерсесяна

- ^ Лазарев В. Н. Андрей Рублев и его школа. М.,1966. С. 61–62

- ^ http://www.wellsprings.org.uk/rublevs_icon/christ.htm

- ^ http://www.wellsprings.org.uk/rublevs_icon/Spirit.htm

- ^ Гуляева, Е. Ю. "«ТРОИЦА» АНДРЕЯ РУБЛЕВА-ВЕЛИЧАЙШЕЕ ДОСТИЖЕНИЕ РУССКОГО ДУХА." Ежемесячный научный журнал № 6/2014. http://social-scope.ru/files/ARHIV/29-30.12.2014/scope_6_december.pdf#page=33

- ^ "Оклад "Троицы"". Портал «Культура России». Archived from the original on 2012-02-26. Retrieved 2008-12-23.

- ^ a b c d А. Никитин. Загадка «Троицы» Рублева. (Первая публикация: Никитин А. Кто написал «Троицу Рублева»? // НиР, 1989, № 8–9.)

- ^ Стоглав. Изд. Д. Е. Кожанчикова. СПб., 1863, с. 128

- ^ Nikitin, Andreĭ Leonidovich (2001). Основания русской историй: мифологемы и факты (in Russian). Аграф.

The Legend on Saint Icon Painters: "Преподобный отец Андрей радонежский, иконописец, прозванием Рублев, многая святыя иконы писал, все чудотворные. Яко же пишет о нем в Стоглаве святого чудного Макария митрополита, что с его письма писати иконы, а не своим умыслом. А преже живяше в послушании у преподобного отца Никона Радонежского. Он повеле при себе образ написати святыя Троицы в похвалу отцу своему святому Сергию Чудотворцу". - ^ Святая Троица Андрея Рублева. Описание, история иконы

- ^ Балязин, Вольдемар Николаевич (2007). Неофициальная история России (in Russian). ОЛМА Медиа Групп. p. 71. ISBN 5373012297.

- ^ ""Троица" на Икон-арт.инфо". Archived from the original on 2012-02-26. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ^ (Горский А. В.). Историческое описание Свято-Троицкия Сергиевы лавры. М., 1857, с. 10.

- ^ (Насонов А. Н. Новые источники по истории Казанского «взятия». — Археографический ежегодник за 1960 год. М., 1962, с. 10)

- ^ (Клосс 1998, с. 83)

- ^ "Андрей Рублев. Биография. Произведения. Источники. Литература". Archived from the original on 2012-02-26.

- ^ Анисимов А. И. Научная реставрация и «Рублевский вопрос». /'/ Анисимов А. И. О древнерусском искусстве. М., 1983, с. 105—134.

- ^ Айналов Д. В. История русской живописи от XVI по XIX столетие. СПб., 1913, с. 17

- ^ Пунин Н. Андрей Рублев. Пп, 1916

- ^ Лазарев В. Н. Русская средневековая живопись. М., 1970, с. 299

- ^ "Реставрация икон. Методические рекомендации". Archived from the original on 2012-02-26. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ^ a b c d e Ю. Г. Мальков. К изучению «Троицы» Андрея Рублева. // Музей № 8. Москва, Советский художник, 1987. c.238–258

- ^ Гурьянов В. П. Две местные иконы св. Троицы в Троицком соборе Свято-Троицко-Сергиевой лавры и их реставрация. М., 1906 г.

- ^ Андрей Рогозянский. "Троица Рублёва, тихое озарение Сергиевской Руси". Archived from the original on 2012-02-26. Retrieved 2008-12-26.

- ^ "Блог Л. В. Нерсесяна". Archived from the original on 2012-02-26. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

Further reading

- Saint Thomas Aquinas. "Thankagiving prayer after Mass". Archived from the original on January 20, 2018.

"And I pray that You will lead me, a sinner, to the banquet where you, with Your Son and holy Spirit, are true and perfect light, total fulfillment, everlasting joy, gladness without end, and perfect happiness to your saints. grant this through Christ our Lord. Amen."

- Gabriel Bunge, "The Rublev Trinity: The Icon of the Trinity by the Monk-Painter Andrei Rublev", Crestwood, NY, St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 2007.

- Troitca Andreya Rubleva [The Trinity of Andrey Rublev], Gerold I. Vzdornov (ed.), Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1989.

- Konrad Onasch, Das Problem des Lichtes in der Ikonomalerei Andrej Rublevs. Zur 600–Jahrfeier des grossen russischen Malers, vol. 28. Berlin: Berliner byzantinische Arbeiten, 1962.

- Eugeny N. Trubetskoi, Russkaya ikonopis'. Umozrenie w kraskah. Wopros o smysle vizni w drewnerusskoj religioznoj viwopisi [Russian icon painting. Colourful contemplation.

- Natalya A. Demina, Troitca Andreya Rubleva [The Trinity of Andrey Rublev]. Moscow: Nauka, 1963.

- Mikhail V. Alpatov, Andrey Rublev, Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1972.

- Florensky, Pavel A. Troitse-Sergieva Lavra i Rossiya [The Troitse-Sergiev's Lavra and Russia]. In Troitsa Andreya Rubleva [The Trinity of Andrey Rublev], Gerold I. Vzdornov (ed.), 52–53, Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1989.

- Nikolai A. Golubtsov, Presyataya Troitsa I domostroitel’stvo (Ob ikone inoka Andreya Rubleva) [The Holy Trinity and housebuilding (On the icon of Holy Trinity by Andrey Rublev)], Journal of Moscow Patriarchate 7, 32–40, 1960.

- Sergius Golubtsov, Ikona jivonachal’noy Troitsy [The icon of live-creating Trinity], Journal of Moscow Patriarchate 7, 69–76, 1972.

- Viktor N. Lazarev, Russkaya srednevekovaya zhivopis’ [Medieval Russian art], In Troitsa Andreya Rubleva [The Trinity of Andrey Rublev], Gerold I. Vzdornov (ed.), 104–110. Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1989.

- Henri J. M. Nouwen, Behold the Beauty of the Lord: Praying with Icons, Notre Dame, Ind., AveMariaPress, 1987, pp. 23–24

- Jinkins, Michael (2001). Invitation to Theology: A Guide to Study, Conversation & Practice. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Georgij Yu. Somov, Semiotic systemity of visual artworks: Case study of The Holy Trinity by Rublev . Semiotica 166 (1/4), 1–79, 2007. Alternative link.

- Huelin, Scott, "The Hospitality of Abraham: A Meditation," SEEN Journal 14/2 (spring 2014), pp. 16–18. Alternative link.

- A. Kriza, "Legitimizing the Rublev Trinity: Byzantine iconophile arguments in medieval Russian debates over the representation of the Divine," Byzantinoslavica 74 (2016) 134–152

External links

- "Trinity by Andrei Rublev" (in Russian). Tretyakov Gallery official website.