Godfrey Herbert

Godfrey Herbert | |

|---|---|

| Nickname(s) | Baralong Herbert |

| Born | 28 February 1884 Coventry, England |

| Died | 8 August 1961 (aged 77) Umtali, Southern Rhodesia |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1898–1919; 1939–1943 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Battles / wars | First World War Second World War |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Order and Bar |

Captain Godfrey Herbert, DSO and bar, (28 February 1884 – 8 August 1961) was an officer of the Royal Navy who was sometimes referred to as 'Baralong Herbert', in reference to the Baralong incidents, alleged British war crimes that took place during World War I. In a naval career stretching from 1898 to 1919, and with a return to duty between 1939 and 1943 in World War II, Herbert had several close encounters with death.[1]

Early life

Godfrey Herbert was born on 28 February 1884 in Coventry. His father was a local solicitor, John Herbert, and his mother was Lucy Mary Herbert (née Draper). He attended Stubbington House School in the village of Stubbington, Hampshire.[1] This was an early example of a preparatory school established primarily with the purpose of educating boys for service in the Royal Navy and it was probably the most successful of such institutions, becoming known as "the cradle of the navy".[2][3] Following a period at Littlejohn's School, a naval crammer in Greenwich, Herbert became a naval cadet on HMS Britannia in 1898,[4] and in June 1900 was enlisted as a midshipman in the Navy.[1]

Submarines

Following promotion to sub-lieutenant in 1903 and specialised training in submarine technology on depot ship HMS Thames in 1905, Herbert became second-in-command of HMS A4, an early British submarine. His superior was Eric Nasmith, slightly older than Herbert and who had been educated at another well-known naval preparatory school, Eastman's Royal Naval Academy; Nasmith was to be awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions in the Gallipoli Campaign.[1][5] The two men and their crew survived when the A4 sank in 90 feet (27 m) of water a few months later. The Times commented that:

Nothing but the admirable steadiness of the men and the splendid presence of mind of Lieutenant Nasmith and Sub-Lieutenant Herbert could have saved the country from another appalling submarine disaster.[4]

Herbert was called to give evidence in October 1905 at the court martial of Nasmith, who was reprimanded for the events of that day.[6]

Promoted to the rank of lieutenant in December 1905, Herbert then spent some time gaining experience on non-submarine ships prior to taking command of the submarine HMS C36. In February 1911,[1] C36 was transferred to Hong Kong under his command for operational service with the China Squadron. This was a record-breaking and hazardous voyage for the period, given the unreliability of early submarines. On his return in 1913, he commanded HMS C30 for a time.[4]

Herbert was commanding HMS D5 at the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, and his time in charge of that submarine, prior to moving to Q-ships in January 1915, was not without incident. He had already risked his life on C36 when he reattached a hawser connecting the vessel to the ship that was towing it during a storm in the Red Sea, and on D5 he experienced an incident where two torpedoes launched at the German light cruiser SMS Rostock missed their target because they were 40 pounds (18 kg) heavier than the versions used in training. That incident occurred on 21 August and, on 3 November, D5 hit a floating mine while voyaging to combat the raid on Yarmouth. The ship sank within a minute and few of the crew survived, of whom Herbert was one.[1][4] Paul Halpern, a naval historian and biographer of Herbert, says that this was a British mine that had come loose but The Times reported in 1929 that it was one that had been laid by German battle cruisers as they retreated from a raid on Great Yarmouth.[7]

Service in Q-ships

Q-ships were heavily armed merchant ships with concealed weaponry, designed to lure submarines into making surface attacks. This gave Q-ships the chance to open fire and sink them. Herbert's transfer to that arm of the Navy arose from there being no submarines available of which he could take command following the sinking of the D5.[4]

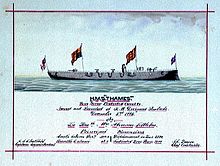

His first Q-ship was a converted steam packet – RMS Antwerp, owned by the Great Eastern Railway – whose peacetime operations had been primarily on the route between Harwich and Hook of Holland.[8] With this he had no notable success and in April 1915 he was transferred to command HMS Baralong, the vessel that was to give him the unwanted nickname of 'Baralong Herbert'.[1] In command, he was known by the merchant navy pseudonym 'Captain William McBride'.[9]

Baralong had been built as a steam cargo liner and was converted for wartime use in March 1915, although the Q-ship campaign did not officially begin until after the events in which she is remembered and it was those events that encouraged the official recognition.[10] She was falsely flying the flag of the then-neutral United States when she answered an SOS call from a merchant ship, SS Nicosian, which was being pursued by a German submarine around 80 nautical miles (150 km) west of the Scillies. The Nicosian was carrying a cargo of munitions from the United States to Britain as well as mules for military use. The subsequent events are mired in controversy and differences of opinion regarding fact.[1]

The commandant of the German SM U-27, Bernard Wegener, would have been within his rights under the Prize Regulations to commence shelling once the vessel was crew-less. Naval historian Dwight Messimer believes that the crew had in fact abandoned ship and that this was what was happening when Herbert arrived. According to Messimer, U-27 stopped firing on Nicosian when Baralong signalled that she was going to rescue the crew. Instead, Baralong took advantage of being screened from the submarine by the merchant ship in order to raise the Royal Navy's White Ensign in replacement for the false flag, and then to launch a devastating attack on U-27 as she came into view once more. The German vessel sank within a minute and the only survivors were the 12 men who were manning deck guns and in the conning tower.[11]

Other writers differ from Messimer on a significant detail. Gibson and Prendergast say that SOS messages were still being sent from the Nicosian when Herbert arrived, implying that at least some crew were still on board while U-27 commenced shelling. Halpern equivocates on the issue: they may or may not all have abandoned ship by that time. Both of these sources also say that a second German submarine was present.[1][12]

The surviving U-27 crew swam towards the Nicosian for safety. Being aware of the cargo and that the Nicosian also had some rifles and ammunition on board, Herbert feared that any boarding German sailors might seek to destroy the cargo by setting fire to the fodder or might even attempt to scuttle the ship. He thus sent a party of Royal Marines aboard with orders to shoot the German sailors and to do so without granting mercy. Feelings had been running high in the aftermath of the sinking of the RMS Lusitania in May 1915 and the sinking of a liner, SS Arabic, earlier in the day of 19 August. The four[12] fugitives were found below deck and the order was carried out. With the other eight German crew having been shot and killed while still in the sea, there were no survivors from U-27.[1][11] The Nicosian was then re-boarded by her crew and made the journey into Avonmouth despite being holed.[12]

The affair was hushed up in Britain at the time, but the story became news when some American members of Nicosian's crew (mostly employed as muleteers) returned to the US and some of her crew spoke with news reporters. Having been subjected to various accusations of war crimes, the Germans saw an opportunity to lay such a charge against their enemies, demanding that Herbert should be tried for murder and pointing to both the deaths and the misuse of the US flag. The story was played out in the newspapers and in diplomatic back-and-forth but without any specific outcome.[1][13] An impasse was reached when German demands for an impartial inquiry[14] met with a British counter-response: they were happy to see the matter investigated in such a way but only if three recent incidents of German aggression were considered at the same time. Those incidents were the sinking of the Arabic; the wounding and killing in their lifeboats of some crew from the Ruel, who had abandoned their collier after a U-boat shelled it; and the killing by German destroyers of some crew of HMS E15 while it was stranded in Danish territorial waters.[10][a] In the wider context, Halpern believes that the incident "... became one of the most celebrated of the war and a German justification for the adoption of unrestricted submarine warfare."[1]

The British Admiralty decorated Herbert with the DSO and appear to have tried to prevent any recriminations in the event that he was captured by continuing to name the commander of the Baralong as being 'Captain William McBride'.[1] Herbert's identity remained hidden from many until the publication of E. Keble Chatterton's biography of the man – Amazing Adventure – in 1935. With that, The Times noted that Herbert had "packed into his sea-life sufficient material for half-a-dozen thrillers".[16][b]

K13 sinking

Herbert returned to submarine warfare briefly, taking command of HMS E22, and was then assigned to Carrigan Head, which was configured as a Q-ship. Subsequently, he requested a return to submarines and, in October 1916, was put in command of HMS K13. This vessel, which was still under construction at the time, was of the steam-powered K-class.[1] Although Herbert's prior commands had been with both petrol- and diesel-powered submarines,[4] he had sampled the problems of steam power in December 1914 when acting as British Liaison Officer on board the French submarine, Archimède. On that occasion, while patrolling off Heligoland, high seas proved too much for the submarine to proceed on the surface and her funnel was damaged when she manoeuvred in an attempt to return to port. The damage made it impossible to fully retract and seal off the funnel, and thus impossible to dive. Her crew had to endure considerable hardship in atrocious weather, baling out incoming water with a bucket brigade on the voyage to safety. Herbert won the hearts of the crew by assisting with the baling and by his encouraging comments.[18]

The French had tended to persist with their steam-powered designs despite some glaring problems, and the British Admiralty went ahead with both HMS Swordfish and the K Class of steam submarines even though aware of those problems. Neither design was a success.[18] K13 sank in Gareloch, Argyll, Scotland, on 29 January 1917, having signalled that she was about to dive. There were 80 people on board, including some civilians. As she dived, seawater entered her engine room and flooded it along with the aft torpedo room. Two men were seen on the surface by a maid in a hotel a mile or so away, but her report was ignored and the alarm was raised when crew of HMS E50 became concerned when the submarine did not surface again and they found traces of oil on the surface. Despite the lack of proper escape apparatus, Herbert and the captain of HMS K14, Goodhart, who was also on board, attempted an escape to the surface by using the space between the inner and outer hatches of the conning tower as an airlock. Herbert reached the surface alive, but Goodhart's body was later found trapped in the superstructure.[c] Eventually, the bows were brought to just above the surface and the final survivor emerged 57 hours after the accident. Including Goodhart, 32 people died in the accident and 48 were rescued. 31 were expected to be still on the submarine, but only 29 were found, and it was concluded that the maid had indeed seen two people escaping from the engine room. One of their bodies was recovered from the Clyde two months later. A later enquiry determined that K13 had dived with various ventilators and the engine room hatch still open, despite warning lights to that effect.

Return to Q-ships

Herbert returned to duty on Q-ships, commanding a flotilla of four trawlers – the Sea King, Sea Sweeper, Nelly Dodds and W. H. Hastie.[19] These were equipped with the recently introduced hydrophone technology and, while patrolling off the coast of The Lizard in Cornwall, they were the first that were thus equipped to have success. That success, however, was not due to the hydrophones: on 12 June 1917, Sea King sighted a submarine, allegedly SM UC-66, on the surface and in moving towards it caused the submarine to dive. The flotilla then let loose their depth charges. It was only after the event that the hydrophones were used, with the purpose being to detect any sound that might indicate the enemy had survived. They heard nothing.[20] The identification of the submarine is questionable, as the Wiki entry for UC-66 states that it had already been sunk by HM seaplane No. 8656 off the Isles of Scilly on 27 May 1917.

Herbert was promoted to the rank of commander and belatedly, in 1919, he was awarded a bar to his DSO when the identity and destruction of UC-66 had been confirmed.[1][4] Later still, in 1921, he gave evidence at a Prize Court investigating the award of bounties for the sinking of enemy submarines. Each of the trawlers received £145.[19]

In November 1919, soon after the end of the war, Herbert retired from the Navy. He had completed his service by working on the staff of Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly at Queenstown in Ireland and with a brief period spent in the Baltic Sea on HMS Caledon, a C-class cruiser.[1]

Later life

Herbert became a sales manager for the Daimler car division of the Birmingham Small Arms Company,[4] of which he had become a director by 1931.[21]

With the outbreak of World War II, Herbert saw action once again. He commanded the armed merchant cruiser Cilicia, which was involved mostly in the escort of convoys off the coast of West Africa. He retired from duty once more in 1943 and settled in Beira, Mozambique, where he became managing director of Allen, Wack, and Shepherd Ltd, a forwarding agency that was part of British Overseas Stores.[4][22]

Herbert had married Ethel Ellen Nelson,[d] the widow of a Royal Marines officer, on 3 May 1916 and with her he had two daughters. Having moved to Umtali, Southern Rhodesia, in 1948, he was chairman of three different companies. He died there, still in office at two of those companies, on 8 August 1961.[1][4]

References

Notes

- ^ Germany did eventually attempt to mollify the anger of the United States regarding the Arabic sinking, although without much success.[15]

- ^ Despite the pre-publication comments made by The Times, when Chatterton's biography was eventually reviewed the newspaper remarked that "Commander Herbert's War service was exciting and creditable, but it may be doubted if his naval career really provides material for a whole book".[17]

- ^ Paul Halpern says that this was a deliberate escape attempt[1] but Herbert's obituarist in The Times, B. J. Howard, believed it was itself an accident and that "... while investigating with another officer the situation of those of the crew from whom he was cut off, [they were] accidentally projected to the surface through the water-filled conning tower".[4]

- ^ The notification of his death records his wife's name as being Elizabeth.[23]

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Halpern, Paul G. (2008), "Herbert, Godfrey (1884–1961)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press, retrieved 2 December 2012 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^

"The History of the Crofton Community Centre", Crofton Community Centre http://www.croftoncommunitycentre.org/history.php, retrieved 5 December 2012

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Leinster-Mackay (1984), pp. 66–68

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Howard, B. J. (26 August 1961), "Captain Godfrey Herbert", The Times, p. 10, retrieved 5 December 2012 (subscription required)

- ^ Woolven, Robin (2008), "Nasmith, Sir Martin Eric Dunbar- (1883–1965)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press, retrieved 2 December 2012 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ Gibson & Prendergast (2002), p. 47

- ^ Messimer, Dwight R (2002). Verschollen: World War I U-boat Losses. Naval Institute Press. p. 23. ISBN 1-55750-475-X.

- ^ a b Gibson & Prendergast (2002), pp. 53–54

- ^ a b Messimer (2002), pp. 46–47 sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMessimer2002 (help)

- ^ a b c Gibson & Prendergast (2002), pp. 52–53

- ^ "The 'Baralong Case'", The Times, p. 6, 5 January 1916, retrieved 7 December 2012 (subscription required)

- ^ "Memorandum of the German Government ... and reply of His Majesty's Government thereto". WWW Virtual Library. Retrieved 8 December 2012.[note: the British reply is not included]

- ^ Gibson & Prendergast (2002), p. 59

- ^ "Books To Come", The Times, p. 22, 4 June 1935, retrieved 5 December 2012 (subscription required)

- ^ "A 'Q-Ship' Commander", The Times, p. 8, 14 June 1935, retrieved 5 December 2012 (subscription required)

- ^ a b Compton-Hall (2004), pp. 90–91 sfnp error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFCompton-Hall2004 (help)

- ^ a b "The Prize Court", The Times, p. 4, 17 February 1921, retrieved 5 December 2012 (subscription required)

- ^ Gibson & Prendergast (2002), pp. 186–188

- ^ "The Birmingham Small Arms Company", The Times, p. 17, 28 November 1931, retrieved 5 December 2012 (subscription required)

- ^ "British Overseas Stores", The Times, p. 8, 30 October 1944, retrieved 5 December 2012 (subscription required)

- ^ "Deaths", The Times, p. 1, 9 August 1961, retrieved 5 December 2012 (subscription required)

Bibliography

- Compton-Hall, Richard (2004) [1983], First Submarines: The Beginnings of Underwater Warfare, Penzance: Periscope Publishing, ISBN 978-1-904381-19-8

- Gibson, R. H.; Prendergast, Maurice (2002) [1931], German Submarine War 1914–1918, Periscope Publishing, ISBN 978-1-904381-08-2

- Leinster-Mackay, Donald P. (1984), The Rise of the English Prep School, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-905273-74-7

- Messimer, Dwight R. (2002), Verschollen: World War I U-Boat Losses, Naval Institute Press, ISBN 978-1-55750-475-3

Further reading

- Bishop, Patrick (2012). Target Tirpitz: X-Craft, Agents and Dambusters — The Epic Quest to Destroy Hitler's Mightiest Warship. HarperCollins UK. ISBN 978-0-00-731926-8.

- Bridgland, Tony (1999). Sea killers in disguise: the story of Q-ships and decoy ships in the first World War. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-895-9.

- Chadwick, Elizabeth (August 2007). "The "Impossibility" of Maritime Neutrality During World War 1". Netherlands International Law Review. 54 (2): 337–360. doi:10.1017/S0165070X07003373.

- Coder, Barbara J. (2000). Q-Ships of the Great War. Maxwell AFB: Air University Press.

- Coles, Alan (1986). Slaughter at sea: the truth behind a naval war crime. London: Robert Hale. ISBN 978-0-7090-2597-9.

- Compton-Hall, Richard (2004). Submarines at War 1914–1918 (Reprinted ed.). Periscope Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904381-21-1.

- Everitt, Don (1974) [1963]. The K Boats. London: George Harrap & Co. OCLC 254477370.

- Halpern, Paul G. (2012) [1995]. A Naval History of World War I. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-61251-172-6.

- Lake, Simon (May 1906). "The Submarine Versus The Submersible". Journal of the American Society for Naval Engineers. 18 (2): 533–545. doi:10.1111/j.1559-3584.1906.tb05792.x.

- McGill, Harold W.; Norris, Marjorie Barron (2007). Medicine and Duty: The World War I Memoir of Captain Harold W. McGill, Medical Officer, 31st Battalion, C.E.F. University of Calgary Press. ISBN 978-1-55238-193-9.

- Nolan, Liam; Nolan, John E. (2009). Secret Victory: Ireland and the War at Sea, 1914–1918. Mercier Press. ISBN 978-1-85635-621-3.

- Thompson, Julian (2011). Imperial War Museum Book of the War at Sea 1914–18. Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-330-54076-6.

- Walker, Mick (2004). The BSA Gold Star. Redline Books. ISBN 978-0-9544357-3-8.

- Zetterling, Nikl; Tamelander, Michael (2009). Tirpitz: The Life and Death of Germany's Last Super Battleship. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1-935149-18-7.