Acanthus (ornament)

The acanthus is one of the most common plant forms to make foliage ornament and decoration.[1]

Architecture

In architecture, an ornament may be carved into stone or wood to resemble leaves from the Mediterranean species of the Acanthus genus of plants, which have deeply cut leaves with some similarity to those of the thistle and poppy. Both Acanthus mollis and the still more deeply cut Acanthus spinosus have been claimed as the main model, and particular examples of the motif may be closer in form to one or the other species; the leaves of both are in any case, rather variable in form. The motif is found in decoration in nearly every medium.

The relationship between acanthus ornament and the acanthus plant has been the subject of a long-standing controversy. Alois Riegl argued in his Stilfragen that acanthus ornament originated as a sculptural version of the palmette, and only later, began to resemble Acanthus spinosus.[2]

Greek and Roman

In Ancient Greek architecture acanthus ornament appears extensively in the capitals of the Corinthian and Composite orders, and applied to friezes, dentils, and other decorated areas. The oldest known example of a Corinthian column is in the Temple of Apollo Epicurius at Bassae in Arcadia, c. 450–420 BC, but the order was used sparingly in Greece before the Roman period. The Romans elaborated the order with the ends of the leaves curled, and it was their favourite order for grand buildings, with their own invention of the Composite, which was first seen in the epoch of Augustus.[3] Acanthus decoration continued in popularity in Byzantine, Romanesque, and Gothic architecture. It saw a major revival in the Renaissance, and still is used today.

The Roman writer Vitruvius (c. 75 – c. 15 BC) related that the Corinthian order had been invented by Callimachus, a Greek architect and sculptor who was inspired by the sight of a votive basket that had been left on the grave of a young girl. A few of her toys were in it, and a square tile had been placed over the basket, to protect them from the weather. An acanthus plant had grown through the woven basket, mixing its spiny, deeply cut leaves with the weave of the basket.

Byzantine

Some of the most detailed and elaborate acanthus decoration occurs in important buildings of Byzantine architecture, where the leaves are undercut, drilled, and spread over a wide surface. Use of the motif continued in Medieval art, particularly in sculpture and wood carving and in friezes, although usually it is stylized and generalized, so that one doubts that the artists connected it with any plant in particular. After centuries without decorated capitals, they were revived enthusiastically in Romanesque architecture, often using foliage designs, including acanthus. Curling acanthus-type leaves occur frequently in the borders and ornamented initial letters of illuminated manuscripts, and are commonly found in combination with palmettes in woven silk textiles. In the Renaissance classical models were followed very closely, and the acanthus becomes clearly recognisable again in large-scale architectural examples. The term is often also found describing more stylized and abstracted foliage motifs, where the similarity to the species is weak.

Gallery

-

Roman-period Greek Corinthian capital, 14 AD

-

The type of palmette commonly found as an acroterion

-

Byzantine capital from Hagia Sophia, Istanbul

-

Twelfth Century Acanthus capital at St Bees Priory, England

-

Unusually elaborate Early Renaissance capital on the Doge's Palace in Venice

-

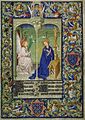

Illuminated Book of Hours with acanthus leaf ornamental border, c. 1406–09

-

Silk fabric with acanthus and palmette design in a portrait of Edward IV of England (1442-1483)

-

Profusion of Baroque acanthus ornament on the Cathedral of Syracuse, Sicily]]

-

Acanthus motifs in an English Baroque stair baluster, c. 1700

-

Very stylized acanthus motif engraving on an ennobled watch movement

-

Acanthus wallpaper designed by William Morris, 1875

-

Fourth-century Roman silver jug from the Water Newton Treasure, with acanthus decoration in two of the zones

-

Third-century Roman floor mosaic

-

Penfold design pillar box decorated with Acanthus leaves on cap, 1866–79, UK

See also

References

- ^ Lewis, Philippa; Darley, Gillian (1986). Dictionary of Ornament. New York: Pantheon. p. not cited.

- ^ Riegl, A; Kain, E (trans.) (1992). Problems of style: foundations for a history of ornament. Princeton. pp. 187–206.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Strong, D.E. (1960). "Some early examples of the composite capital". Journal of Roman Studies. 50: 119–128.

External links

Media related to Acanthus ornaments at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Acanthus ornaments at Wikimedia Commons

![Profusion of Baroque acanthus ornament on the Cathedral of Syracuse, Sicily]]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/40/0608_-_Siracusa_-_Facciata_del_Duomo_-_Foto_Giovanni_Dall%27Orto%2C_22_May_2008.jpg/120px-0608_-_Siracusa_-_Facciata_del_Duomo_-_Foto_Giovanni_Dall%27Orto%2C_22_May_2008.jpg)