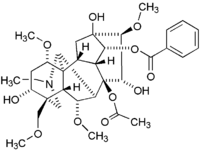

Aconitine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(1α,3α,6α,14α,16β)-8-(acetyloxy)-20-ethyl-3,13,15-trihydroxy-1,6,16-trimethoxy-4-(methoxymethyl)aconitan-14-yl benzoate

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.566 |

PubChem CID

|

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| Properties | |

| C34H47NO11 | |

| Molar mass | 645.73708 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Aconitine (sometimes known as the Queen of Poisons) is a highly poisonous alkaloid derived from various aconite species.

Uses

It is a neurotoxin that opens TTX-sensitive Na+ channels in the heart and other tissues,[1] and is used for creating models of cardiac arrhythmia. Aconitine was previously used as an antipyretic and analgesic, and still has some limited application in herbal medicine although the narrow therapeutic index makes calculating appropriate dosage difficult.[2]

Composition

Aconitine has the chemical formula C34H47NO11, and is soluble in chloroform or benzene, slightly in alcohol or ether, and only very slightly in water.

The Merck Index gives LD50s for mice: 0.166 mg/kg (intravenously); 0.328 mg/kg intraperitoneally (injected into the body cavity); approx. 1 mg/kg orally (ingested).[3] In rats, the oral LD50 is given as 5.97 mg/kg. Oral doses as low as 1.5–6 mg aconitine were reported to be lethal in humans.[4]

Effects

It is quickly absorbed via mucous membranes, but also via skin. Respiratory paralysis, in very high doses also cardiac arrest, leads to death. A few minutes after ingestion paresthesia starts, which includes tingling in the oral region. This extends to the whole body, starting from the extremities. Anesthesia, sweating and cooling of the body, nausea and vomiting and other similar symptoms follow. Sometimes there is strong pain, accompanied by cramps, or diarrhea. There is no antidote, so only the symptoms can be treated,[5] traditionally with compounds such as atropine, strychnine or barakol, although it is unclear whether any of these are effective. Some other toxins such as tetrodotoxin which bind to the same target site but have opposite effects, can reduce the effects of aconitine, but are so toxic themselves that death may result regardless.[6] The anti-dysrhythmic drug lidocaine, which is clinically used for treating unusual cardiac rhythms, also blocks these sodium channels and there is a single report of a successful treatment of accidental aconitine poisoning using this drug.[7] Serum or urine concentrations of the chemical may be measured to confirm diagnosis in hospitalized poisoning victims, while postmortem blood levels have been reported in at least 5 fatal cases[8]

Aconite poisoners

Aconitine was the poison used by George Henry Lamson in 1881 to murder his brother-in-law in order to secure an inheritance. Lamson had learnt about aconitine as a medical student from Professor Robert Christison, who had taught that it was undetectable—but forensic science had improved since Lamson's student days.[9][10][11]

Aconitine was also made famous by its use in Oscar Wilde's 1891 story Lord Arthur Savile's Crime. Aconite also plays a prominent role in James Joyce's Ulysses, in which the protagonist Leopold Bloom's father used pastilles of the chemical to commit suicide.

In 2009 Lakhvir Singh of Feltham, west London, used aconitine to poison the food of her ex-lover (who died as a result of the poisoning) and his current fiancée in what is believed to be the first such case since Lamson's use of the poison. Singh has since received a life sentence for the murder.[12]

References

- ^ Wang SY, Wang GK (2003). "Voltage-gated sodium channels as primary targets of diverse lipid-soluble neurotoxins". Cellular Signalling. 15 (2): 151–9. doi:10.1016/S0898-6568(02)00085-2. PMID 12464386.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Chan TY (2009). "Aconite poisoning". Clinical Toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa.). 47 (4): 279–85. doi:10.1080/15563650902904407. PMID 19514874.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Merck & Co. (1989): The Merck Index. Eleventh Edition: p.117. Rahway, N.J.. ISBN 091191028X

- ^ Ludewig, R., Regenthal, R. et al. (2007): Akute Vergiftungen und Arzneimittelüberdosierungen (German). ISBN 3-8047-2280-6.

- ^ Roth, L., Daunderer, M. & Kormann, K. (1994): Giftpflanzen - Pflanzengifte. ISBN 3-933203-31-7.

- ^ Ohno Y, Chiba S, Uchigasaki S, Uchima E, Nagamori H, Mizugaki M, Ohyama Y, Kimura K, Suzuki Y (1992). "The influence of tetrodotoxin on the toxic effects of aconitine in vivo". The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine. 167 (2): 155–8. doi:10.1620/tjem.167.155. PMID 1475787.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tsukada K, Akizuki S, Matsuoka Y, Irimajiri S (1992). "[A case of aconitine poisoning accompanied by bidirectional ventricular tachycardia treated with lidocaine]". Kokyu to Junkan. 40 (10): 1003–6. PMID 1439251.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Macinnis, Peter (2006). It's true!: you eat poison every day. It's true. Vol. 18. Allen & Unwin. pp. 80–81. ISBN 1741146267.

- ^ Macinnis, Peter (2005). Poisons: from hemlock to Botox and the killer bean of Calabar. Arcade Publishing. pp. 25–26. ISBN 1559707615.

- ^ Parry, Leonard A. (2000). Some Famous Medical Trials. Beard Books. p. 103. ISBN 1587980312.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Poisoning in west London in 2009 - BBC TV News report 10 February 2010.