American realism

American realism was a movement in art, music and literature that depicted contemporary social realities and the lives and everyday activities of ordinary people. The movement began in literature in the mid-19th century, and became an important tendency in visual art in the early 20th century. Whether a cultural portrayal or a scenic view of downtown New York City, American realist works attempted to define what was real.

In the U.S. at the beginning of the 20th century a new generation of painters, writers and journalists were coming of age. Many of the painters felt the influence of older U.S. artists such as Thomas Eakins, Mary Cassatt, John Singer Sargent, James McNeill Whistler, Winslow Homer, Childe Hassam, J. Alden Weir, Thomas Pollock Anshutz, and William Merritt Chase. However they were interested in creating new and more urbane works that reflected city life and a population that was more urban than rural in the U.S. as it entered the new century.

America in the early 20th century

[edit]

From the late 19th to the early 20th centuries, the United States experienced huge industrial, economic, social and cultural change. A continuous wave of European immigration and the rising potential for international trade brought increasing growth and prosperity to America. Through art and artistic expression (through all mediums including painting, literature and music), American realism attempted to portray the exhaustion and cultural exuberance of the figurative American landscape and the life of ordinary Americans at home. Artists used the feelings, textures and sounds of the city to influence the color, texture and look of their creative projects. Musicians noticed the quick and fast-paced nature of the early 20th century and responded with a fresh and new tempo. Writers and authors told a new story about Americans; boys and girls real Americans could have grown up with. Pulling away from fantasy and focusing on the now, American Realism presented a new gateway and a breakthrough—introducing modernism, and what it means to be in the present. The Ashcan school also known as The Eight and the group called Ten American Painters created the core of the new American Modernism in the visual arts.

Ashcan school and the Eight

[edit]

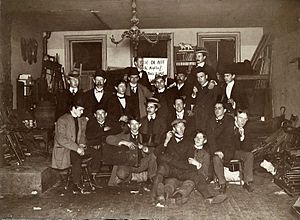

l to r, Everett Shinn, Robert Henri, John French Sloan

The Ashcan school was a group of New York City artists who sought to capture the feel of early-20th-century New York City through realistic portraits of everyday life. These artists preferred to depict the richly and culturally textured lower class immigrants, rather than the rich and promising Fifth Avenue socialites. One critic of the time did not like their choice of subjects, which included alleys, tenements, slum dwellers, and in the case of John Sloan, taverns frequented by the working class. They became known as the revolutionary black gang and apostles of ugliness.[1]

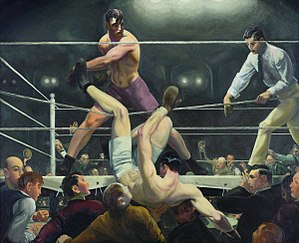

George Bellows

[edit]George Bellows (1882–1925), painted city life in New York City. His paintings had an expressionist boldness and a willingness to take risks. He had a fascination with violence as seen in his 1909 painting Both Members of This Club, which depicts a gory boxing scene. His 1913 painting Cliff Dwellers depicts a city-scape that is not one particular view but a composite of many views.

Robert Henri

[edit]

Robert Henri (1865–1921) was an important American Realist and a member of The Ashcan school. Henri was interested in the spectacle of common life. He focused on individuals, strangers, quickly passing in the streets in towns and cities. His was a sympathetic rather than a comic portrayal of people, often using a dark background to add to the warmth of the person depicted. Henri's works were characterized by vigorous brushstrokes and bold impasto which stressed the materiality of the paint. Henri influenced Glackens, Luks, Shinn and Sloan.[2] In 1906, he was elected to the National Academy of Design, but when painters in his circle were rejected for the academy's 1907 exhibition, he accused fellow jurors of bias and walked off the jury, resolving to organize a show of his own. He later referred to the academy as "a cemetery of art".

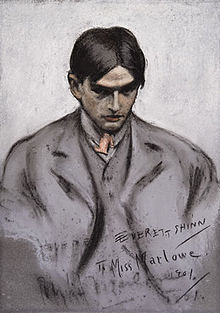

Everett Shinn

[edit]

Everett Shinn (1876–1953), a member of the Ashcan school, was famous for his numerous paintings of New York and the theater, and of various aspects of luxury and modern life inspired by his home in New York City. He painted theater scenes from London, Paris and New York. He found interest in the urban spectacle of life, drawing parallels between the theater and crowded seats and life. Unlike Degas, Shinn depicted interaction between the audience and performer.[3]

George Benjamin Luks

[edit]

George B. Luks (1866–1933) was an Ashcan school artist who lived on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. In Luks' painting Hester Street (1905), he shows children being entertained by a man with a toy while a woman and shopkeeper have a conversation in the background. The viewer is among the crowd rather than above it. Luks puts a positive spin on the Lower East Side by showing two young girls dancing in The Spielers, which is a type of dance among working-class immigrants; despite the poverty, children dance on the street. He looks for the joy and beauty in the life of the poor rather than the tragedy.[3]

William Glackens

[edit]

Early in his career, William Glackens (1870–1938) painted the neighborhood surrounding his studio in Washington Square Park. He also was a successful commercial illustrator, producing numerous drawings and watercolors for contemporary magazines that humorously portrayed New Yorkers in their daily lives. Later in life, he was much better known as "the American Renoir" for his Impressionist views of the seashore and the French Riviera.

John Sloan

[edit]

John Sloan (1871–1951) was an early-20th-century Realist of the Ashcan school, whose concerns with American social conditions led him to join the Socialist Party in 1910.[4] Originally from Philadelphia, he worked in New York after 1904. From 1912 to 1916, he contributed illustrations to the socialist monthly The Masses. Sloan disliked propaganda, and in his drawings for The Masses, as in his paintings, he focused on the everyday lives of people. He depicted the leisure of the working class with an emphasis on female subjects. Among his better known works are Picnic Grounds and Sunday, Women Drying Their Hair. He disliked the category of Ashcan school[5] and expressed his annoyance with art historians who identified him as a painter of the American Scene: "Some of us used to paint little rather sensitive comments about the life around us. We didn't know it was the American Scene. I don't like the name...A symptom of nationalism, which has caused a great deal of trouble in this world."[6]

Edward Hopper

[edit]

Edward Hopper (1882–1967) was a prominent American realist painter and printmaker. Hopper is the most modern of the American realists and the most contemporary. While most popularly known for his oil paintings, he was equally proficient as a watercolorist and printmaker in etching. In both his urban and rural scenes, his spare and finely calculated renderings reflected his personal vision of modern American life.[7]

Hopper's teacher Robert Henri encouraged his students to use their art to "make a stir in the world". He also advised his students "It isn’t the subject that counts but what you feel about it" and "Forget about art and paint pictures of what interests you in life".[8] In this manner, Henri influenced Hopper, as well as students George Bellows and Rockwell Kent, and motivated them to render realistic depictions of urban life. Some artists in Henri's circle, including John Sloan, another teacher of Hopper, became members of the Eight, also known as the Ashcan school of American art.[9] His first existing oil painting to hint at his famous interiors was Solitary Figure in a Theater (c. 1904).[10] During his student years, Hopper also painted dozens of nudes, still lifes, landscapes, and portraits, including his self-portraits.[11]

Other visual artists

[edit]Joseph Stella, Charles Sheeler, Jonas Lie, Edward Willis Redfield, Joseph Pennell, Leon Kroll, B.J.O. Nordfeldt, Gertrude Käsebier, Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, E. J. Bellocq, Philip Koch, David Hanna

-

Alfred Stieglitz, Winter – Fifth Avenue, 1893, photograph

-

Edward Steichen, The Flatiron Building, 1904, photograph

-

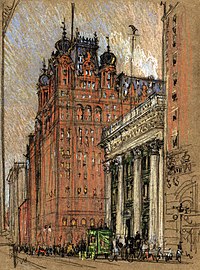

Joseph Pennell, The Waldorf-Astoria, c. 1904–1908, charcoal and pastel on brown paper

-

Edward Willis Redfield, Brooklyn Bridge at Night, 1909, oil on canvas

-

The Old Ships Draw to Home Again, 1920, Jonas Lie, Brooklyn Museum

Writers

[edit]Horatio Alger Jr.

[edit]Horatio Alger Jr. (1832–1899) was a prolific 19th-century American author whose principal output was formulaic rags-to-riches juvenile novels that followed the adventures of bootblacks, newsboys, peddlers, buskers, and other impoverished children in their rise from humble backgrounds to lives of respectable middle-class security and comfort. His novels, of which Ragged Dick is a typical example, were hugely popular in their day.[12]

Stephen Crane

[edit]Stephen Crane (1871–1900), born in Newark, New Jersey, had roots going back to the American Revolutionary War era, soldiers, clergymen, sheriffs, judges, and farmers who had lived a century earlier. Primarily a journalist who also wrote fiction, essays, poetry, and plays, Crane saw life at its rawest in slums and on battlefields. His haunting Civil War novel The Red Badge of Courage was published to great acclaim in 1895, but he barely had time to bask in the attention before he died at 28, having neglected his health. He has enjoyed continued success since his death—as a champion of the common man, a realist, and a symbolist. Crane's Maggie: A Girl of the Streets (1893) is one of the best, if not the earliest, naturalistic American novel. It is the harrowing story of a poor, sensitive girl whose uneducated, alcoholic parents utterly fail her. In love, and eager to escape her violent home, she allows herself to be seduced into living with a young man, who soon deserts her. When her self-righteous mother rejects her, Maggie becomes a prostitute to survive, but soon dies. Crane's earthy subject matter and his objective, scientific style, devoid of moralizing, earmark Maggie as a naturalist work.[13]

William Dean Howells

[edit]William Dean Howells (1837–1920) wrote fiction and essays in the realist mode. His ideas about realism in literature developed in parallel with his socialist attitudes. In his role as editor of the Atlantic Monthly and Harper's Magazine, and as the author of books such as A Modern Instance and The Rise of Silas Lapham, Howells exerted a strong opinion and was influential in establishing his theories.[14][15]

Mark Twain

[edit]Samuel Clemens (1835–1910), better known by his pen name of Mark Twain, grew up in the frontier town of Hannibal, Missouri. Early 19th-century American writers tended to be flowery, sentimental, or ostentatious—partially because they were still trying to prove that they could write as elegantly as the English. Ernest Hemingway in Green Hills of Africa wrote that many Romantics "wrote like exiled English colonials from an England of which they were never a part to a newer England that they were making...They did not use the words that people have always used in speech, the words that survive in language." In the same essay, Hemingway stated that all American fiction comes from Mark Twain's novel The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.[16][17] Twain's style, based on vigorous, realistic, colloquial American speech, gave American writers a new appreciation of their national voice. Twain was the first major author to come from the interior of the country, and he captured its distinctive, humorous slang and iconoclasm. For Twain and other American writers of the late 19th century, realism was not merely a literary technique: It was a way of speaking truth and exploding outworn conventions. Twain is best known for his works Tom Sawyer and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Sam. R. Watkins

[edit]Sam. R. Watkins (1839–1901) was a 19th-century American writer and humorist best known for his memoir Co. Aytch, which recounts his life as a soldier in the Confederate States Army. He "talked in a slow humorous drawl" and demonstrated unusual prowess as a storyteller. One of the book's commendable qualities is its realism. In an age noted for romanticizing "the war" and the men who fought it, he wrote with surprising frankness. The Johnny Rebs of his pages are not all heroes. Soldier life as portrayed by Watkins had more of the dullness and suffering than of excitement and glory. He tells much of the crushing fatigue of long marches; the boredom and discomfort of the long winter lulls; the caprice and harshness of discipline; the incompetency of the officers; the periodic lapses of morale; the uncertainty and meagerness of rations; and the wearying grind of army routine. His accounts of battle make frequent reference to the dreadful screaming of shells, the awful horror of mutilated bodies, and the agonizing cries of the wounded. War as detailed by his pen was a cruel and sordid business.[18]

Others

[edit]Other writers of this sort included Edward Eggleston, Theodore Dreiser, Henry James, Jack London, Upton Sinclair, John Steinbeck, Margaret Deland, Edith Wharton,[19] Ambrose Bierce, and J. D. Salinger.

Journalism

[edit]Jacob Riis

[edit]

Jacob August Riis (1849–1914), a Danish-American muckraker journalist, photographer, and social reformer, was born in Ribe, Denmark. He is known for his dedication to using his photographic and journalistic talents to help the less fortunate in New York City, which was the subject of most of his prolific writings and photographic essays. He helped with the implementation of "model tenements" in New York with the help of humanitarian Lawrence Veiller. As one of the early photographers to use flash, he is considered a pioneer in photography.[20]

Art Young

[edit]Art Young (1866–1943) was an American cartoonist and writer. He is most famous for his socialist cartoons, especially those drawn for the radical magazine The Masses, of which Young was co-editor, from 1911 to 1917. Young started as generally apolitical, but gradually became interested in left wing ideas, and by 1906 or so, considered himself a socialist. He became politically active; by 1910, racial and sexual discrimination and the injustices of the capitalist system became prevalent themes in his work.[21]

Music

[edit]James Allen Bland

[edit]James A. Bland (1854–1919) was the first prominent African-American songwriter[22] and is known for his ballad, Carry me Back to Old Virginny. "In the Evening by the Moonlight" and "Golden Slippers" are well-known songs that he wrote, and he wrote other hits of the period, including "In the Morning by the Bright Light" and "De Golden Wedding". Bland wrote most of his songs from 1879 to 1882; in 1881, he left the U.S. for England with Haverly's Genuine Colored Minstrels. Bland found England more rewarding than the United States and stayed there until 1890; either he stopped writing songs during this period or he was unable to find an English publisher.[22]

C.A. White

[edit]C.A. White (1829–1892) wrote the hit song "Put Me in My Little Bed" in 1869, establishing him as a major songwriter. White was a songwriter of serious aspirations: Many of his songs were written for vocal quartets. He also made several attempts at opera. As half-owner of the music publishing firm White, Smith & Company, he had a ready outlet for his work, but it was his songs that supported the publishing firm and not the other way around. White did not scorn writing for the popular stage—indeed he wrote a song for the pioneering African-American stage production Out of Bondage—but his principal output was for the parlor singer.[23]

W.C. Handy

[edit]W. C. Handy (1873–1958) was a blues composer and musician, often known as the "Father of the Blues". Handy remains among the most influential of American songwriters. Although he was one of many musicians who played the distinctively American form of music known as the blues, he is credited with giving it its contemporary form. While Handy was not the first to publish music in the blues form, he took the blues from a not very well known regional music style to one of the dominant forces in American music. Handy was an educated musician who used folk material in his compositions. He was scrupulous in documenting the sources of his works, which frequently combined stylistic influences from several performers. He loved this folk-musical form and brought a transforming touch to it.[24]

Scott Joplin

[edit]Scott Joplin (c. 1867/68–1917) was an African-American musician and composer of ragtime music and remains the best-known figure. His music enjoyed a considerable resurgence of popularity and critical respect in the 1970s, especially for his most famous composition "The Entertainer".[25]

See also

[edit]- Realism (arts) (includes "naturalism")

- Armory Show

- American modernism

- Photo-Secession

- Modernism

- Ashcan school

- Visual arts of Chicago

- Social realism

References

[edit]- ^ Art Center Information Presents the Ashcan school~Apostles of Ugliness » Art Center Information

- ^ Bennard B. Perlman, Robert Henri: his life and art pp74-79 Dover, 1991 Retrieved August 9, 2010

- ^ a b Shinn, Everett. "Everett Shin on George Luks: An Unpublished Memoir". Archives of American Art. 6.2 (Apr., 1966).

- ^ Loughery, 1997, pp. 144–46.

- ^ Brooks, 1955, p. 79.

- ^ Brooks, 1955, p. 73.

- ^ Sherry Maker, Edward Hopper, Brompton Books, New York, 1990, p. 6, ISBN 0-517-01518-8

- ^ Sherry Maker, Edward Hopper, Brompton Books, New York, 1990, p. 8, ISBN 0-517-01518-8

- ^ Sherry Maker, Edward Hopper, Brompton Books, New York, 1990, p. 9, ISBN 0-517-01518-8

- ^ Gail Levin, Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1995, p. 19, ISBN 0-394-54664-4

- ^ Gail Levin, Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1995, p. 38, ISBN 0-394-54664-4

- ^ Horatio Alger online

- ^ Holton, Milne. Cylinder of Fiction. - The Fiction and Journalistic Writing of Stephen Crane. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1972. 37.

- ^ Crow, Charles L. A companion to the regional literatures of America. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub., 2003: 92. ISBN 0-631-22631-1

- ^ Criticism and Fiction," by William Dean Howells, accessed January 6, 2010.

- ^ "Private Site".

- ^ Hemingway, Ernest (1935). Green Hills of Africa. New York: Scribners. p. 22.

- ^ Watkins, Sam R. (1994) [1st pub. Cumberland Presbyterian Pub. House:1882]. "Co. Aytch", Maury Grays, First Tennessee Regiment: or, A Side Show of the Big Show. With an introd. by Bell Irvin Wiley. Wilmington, N.C.: Broadfoot Pub. Co. pp. 17, 19. ISBN 0-916107-43-4. OCLC 34464004.

- ^ UI Journals

- ^ James Davidson and Mark Lytle, “The Mirror with a Memory, ” After the Fact: The Art of Historical Detection (New York: McGraw Hill, 2000).

- ^ "Art Young". The New York Times. December 31, 1943. Retrieved 2010-10-24.

Art Young, who died in this city Wednesday night at the age of 77, wouldn't have liked to have it said that he was a lovable soul in spite of his sometimes heterodox opinions. He valued his opinions. He had worked them out for himself, and for them he had sacrificed the chance to accumulated a fair share of this world's goods.

- ^ a b "Hall of Fame Retrieved January 14, 2009". Archived from the original on 2009-03-03. Retrieved 2009-01-14.

- ^ Music for the Nation: American Sheet Music, ca. 1870 to 1885 | loc.gov

- ^ Handy, William Christoper (1941). Father of the Blues: An Autobiography. New York: Macmillan. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-306-80421-2.

- ^ The Incredible Story of America's First Pop Star - Polyphonic on YouTube

Sources

[edit]- Brooks, Van Wyck (1955). John Sloan. New York: Dutton.

- Doezema, Marianne, and Elizabeth Milroy (1998). Reading American Art. New Haven: Yale University Press. (pps. 311) ISBN 0300073488.

- Loughery, John (1997). John Sloan: Painter and Rebel. New York: Holt. ISBN 0-8050-5221-6

- Pohl, Frances K. (2002). Framing America: A Social History of American Art. New York, N.Y.: Thames & Hudson. (pp. 302–312) ISBN 0500283346.

External links

[edit]- American Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, a fully digitized 3 volume exhibition catalog

- Music: New Generations of Songwriters

- Literature: American Realism

- Literature: American Realism