Anton Drexler

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2009) |

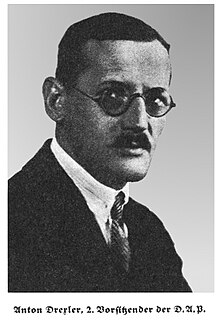

Anton Drexler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chairman of the DAP | |

| In office 5 January 1919 – 29 June 1921 | |

| Deputy | Karl Harrer (1919–1920) |

| Succeeded by | Adolf Hitler |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 13 June 1884 Munich, Germany |

| Died | 24 February 1942 (aged 57) Munich, Germany |

| Political party | DAP NSDAP |

| Occupation | Politician |

Anton Drexler (13 June 1884 – 24 February 1942) was a German far-right political leader of the 1920s who was instrumental in the formation of the pan-German and anti-Semitic German Workers' Party (Deutsche Arbeiterpartei – DAP), the antecedent of the Nazi Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei – NSDAP). Drexler served as mentor to Adolf Hitler during his early days in politics.

Biography

Born in Munich, Drexler was a machine-fitter before becoming a railway toolmaker and locksmith in Berlin.[1] He joined the Fatherland Party during World War I.[2] In March 1918 Drexler founded a branch of the Freien Arbeiterausschuss für einen guten Frieden (Free Workers' Committee for a Good Peace) league.[1] Thereafter in 1918, Karl Harrer (a journalist and member of the Thule Society), convinced Drexler and several others to form the Politischer Arbeiterzirkel (Political Workers' Circle) in 1918.[1] The members met periodically for discussions with themes of nationalism and antisemitism.[1] Drexler was a poet and a member of the völkisch agitators. Together with Harrer, Gottfried Feder and Dietrich Eckart, he founded the German Workers' Party (DAP) in Munich on 5 January 1919.[1]

At a meeting of the Party in Munich in September 1919, the main speaker was Gottfried Feder. When he had finished speaking, Adolf Hitler got involved in a heated political argument with a visitor, Professor Baumann, who questioned the soundness of Feder's arguments against capitalism and proposed that Bavaria should break away from Prussia and found a new South German nation with Austria. In vehemently attacking the man's arguments he made an impression on the other party members with his oratory skills, and according to Hitler, the "professor" left the hall acknowledging unequivocal defeat.[3] Drexler approached Hitler and thrust a booklet into his hand. It was My Political Awakening and, according to Hitler, it reflected the ideals he already believed in.[4] Impressed with Hitler, Drexler invited him to join the DAP. Hitler accepted on 12 September 1919,[5] becoming the party's 55th member.[6] In less than a week, Hitler received a postcard from Drexler stating he had officially been accepted as a DAP member and he should come to a "committee" meeting to discuss it. Hitler attended the "committee" meeting held at the run-down Alte Rosenbad beer-house.[7]

Hitler began to make the party more public, and he organized their biggest meeting yet of 2,000 people, for 24 February 1920 in the Hofbräuhaus in Munich. It was in this speech that Hitler, for the first time, enunciated the twenty-five points of the German Worker's Party's manifesto that had been drawn up by Drexler, Feder, and Hitler.[8] Through these points he gave the organisation a much bolder stratagem[9] with a clear foreign policy (abrogation of The Treaty of Versailles, a Greater Germany, Eastern expansion, exclusion of Jews from citizenship). On the same day the party was renamed the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei – NSDAP (Nazi Party).[10] Such was the significance of this particular move in publicity that Karl Harrer resigned from the party in disagreement.[11]

By 1921, Hitler was rapidly becoming the undisputed leader of the Party. In June 1921, while Hitler and Eckart were on a fundraising trip to Berlin, a mutiny broke out within the NSDAP in Munich. Members of its executive committee wanted to merge with the rival German Socialist Party (DSP).[12] Hitler returned to Munich on 11 July and angrily tendered his resignation. The committee members realised that the resignation of their leading public figure and speaker would mean the end of the party.[13] Hitler announced he would rejoin on the condition that he would replace Drexler as party chairman, and that the party headquarters would remain in Munich.[14] The committee agreed; he rejoined the party as member 3,680. Drexler was thereafter moved to the purely symbolic position of honorary president, and left the Party in 1923.[15]

Drexler was also a member of a völkisch political club for affluent members of Munich society known as the Thule Society. His membership in the NSDAP ended when it was temporarily outlawed in 1923 following the Beer Hall Putsch, in which Drexler had not taken part. In 1924 he was elected to the Bavarian state parliament for another party, in which he served as vice-president until 1928. He had no part in the NSDAP's refounding in 1925, and rejoined only after Hitler had come to power in 1933. He received the party's Blood Order in 1934 and was still occasionally used as a propaganda tool until about 1937, but he was never again allowed any real power or to play an active part in the movement. He died in Munich in February 1942.[16]

In popular culture

In the 2003 miniseries Hitler: The Rise of Evil, British actor Robert Glenister plays Drexler, although Drexler is portrayed without his trademark spectacles and moustache.

Notes

- ^ a b c d e Kershaw 2008, p. 82.

- ^ Hamilton 1984, p. 219.

- ^ Kershaw 2008, p. 75.

- ^ Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf, 1925.

- ^ Stackelberg 2007, p. 9.

- ^ Mitcham 1996, p. 67.

- ^ Kershaw 2008, pp. 75, 76.

- ^ Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, p. 37

- ^ Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, p. 89

- ^ Kershaw 2008, p. 87.

- ^ Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, p. 36

- ^ Kershaw 2008, pp. 100, 101.

- ^ Kershaw 2008, p. 102.

- ^ Kershaw 2008, p. 103.

- ^ Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, p. 41

- ^ Hamilton 1984, p. 220.

References

- Hamilton, Charles (1984). Leaders & Personalities of the Third Reich, Vol. 1. R. James Bender Publishing. ISBN 0-912138-27-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hitler, Adolf (1999) [1925]. Mein Kampf. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-92503-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler: A Biography. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06757-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mitcham, Samuel W. (1996). Why Hitler?: The Genesis of the Nazi Reich. Westport, Conn: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-95485-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shirer, William L. (1960). The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-62420-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stackelberg, Roderick (2007). The Routledge Companion to Nazi Germany. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-30860-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)