Arkadi Monastery

The Arkadi Monastery (in Greek: / Moní Arkadhíou) is an Eastern Orthodox monastery, situated on a fertile plateau 23 km (14 mi) to the southeast of Rethymnon on the island of Crete in Greece.

The current catholicon (church) dates back to the 16th century and is marked by the influence of the Renaissance. This influence is visible in the architecture, which mixes both Roman and baroque elements. As early as the 16th century, the monastery was a place for science and art and had a school and a rich library. Situated on a plateau, the monastery is well fortified, being surrounded by a thick and high wall.

The monastery played an active role in the Cretan resistance of Ottoman rule during the Cretan revolt of 1866. 943 Greeks, mostly women and children,[1] sought refuge in the monastery. After three days of battle and under orders from the hegumen (abbot) of the monastery, the Cretans blew up barrels of gunpowder, choosing to sacrifice themselves rather than surrender.

The monastery became a national sanctuary in honor of the Cretan resistance. 8 November is a day of commemorative parties in Arkadi and Rethymno. The explosion did not end the Cretan insurrection, but it attracted the attention of the rest of the world.

Topography

The Arkadi Monastery is located in the Rethymno regional unit, 25 km southeast of Rethymno. The Monastery is situated on a rectangular plateau on the northwest side of Mount Ida (Crete), at an altitude of 500 m.[2] The Arkadian region is fertile and has vineyards, olive groves and pine, oak and Cyprus forests. The plateau on which the monastery rests is surrounded by hills. The west side of the plateau stops abruptly and falls off into gorges. The gorges start at Tabakaria and lead to Stavromenos, to the east of Rethymno. The Arkadian gorges have a rich diversity of plants and native wildflowers.[3]

The area the monastery is located in first developed in antiquity. The presence of Mount Ida (Crete), which is a sacred mountain because it was legendarily the childhood home of Zeus, made the area attractive to early settlers. Five km to the northeast, the city of Eleftherna had its cultural peak in the time of Homer and in classical antiquity, but its influence was also felt in the early Christian and Byzantine periods.

The closest village to the monastery is Amnatos, located three km to the north. The villages that surround Arkadi are rich in Byzantine relics that prove the early wealth of the region. The Moni Arseniou monastery, which is several km north of Arkadi, was also an example of the grand Cretan monasteries.

Arkadi Monastery is in the shape of a nearly rectangular parallelogram. The interior resembles a fortress and is 78.5 metres long on the north wall, 73.5 metres on the south wall, 71.8 metres on the east wall and 67 metres on the west wall. The total area of the monastery is 5200 m².[4]

History

Founding

The exact date of the founding of the monastery is not precisely known. According to tradition, the foundation of the monastery is sometimes attributed to the Byzantine emperor Heraclius and sometimes to the emperor Arcadius in the 5th century. And, according to the second version, the monastery took its name from the name of the emperor. However, in Crete, it is common for monasteries to be named after the monk that founded the building, which lends support to the theory that Arkadi may have been founded by a monk named Arkadios. Other such monasteries are Vrontisiou, Arsiniou and Aretiou.

According to Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, the monastery was built on the site of an ancient city, Arcadia. Legend tells that after the destruction of Arcadia, all the springs and fountains stopped flowing until a new city was built.[5][Note 1] However, in 1837, Robert Pashley found evidence to suggest that it was impossible for the monastery to have been built on the ruins of another city,[6] so this idea has lost credence.

In 1951, the professor K. Kalokyris published an inscription dating to the 14th century and verified the hypothesis that a monastery was dedicated to Saint Constantine in this period. The inscription was located on the pediment of a church that predates the current one, over the entrance door. It read:

"The church carrying the name of Arkadi is consecrated to Saint Constantine."[Note 2]

Restorations

Towards the end of the 16th century, the monastery was subject to restorations and transformations largely headed by Klimis and Vissarion Chortatzis, without a doubt from the family of Hortatzis of Rethymno (a name associated with the Cretan Renaissance) and Georgios Chortatzis, the author of Erofili. Klimis Hortatzis was the hegumen of the abbey and in 1573, he made the monastery cenobitic.

He oversaw the building of the church, which took twenty-five years and was believed to have begun in 1562.[7] In 1586, the façade of the building was built,[8] as were the two naves. An inscription at the base of the clock also dates it back to 1587. This inscription is as following:

« ΑΦ ΚΛΜΧΤΖ ΠΖ »

or : « 15 Klimis Chortatzis 87 »

Klimis Chortatzis likely died soon after the completion and was not able to attend the inauguration of the new church, which was sometime between 1590 and 1596. This is known thanks to a letter of the Patriarch of Alexandria, Mélétios Pigas, in which he wrote that the inauguration ceremony was entrusted to Klimis's successor, the hegumen Mitrofanis Tsyrigos. Although this letter wasn't dated, one can place it between 1590, when Mélétios Pigas was ordained the Patriarch, and 1596, when the hegumen Nicéphore succeeded Tsygiros.[9]

During the period of the first three hegumens, and up to the beginning of the 17th century, the Arkadi Monastery continued to boom, economically and culturally. The monastery became a great centre for the copying of manuscripts, and although the majority were lost during the destruction of the building by the Ottomans in 1866, some survive in foreign libraries. The monastery grew, with the construction of a stables in 1610 and a refectory in 1670.[8]

Ottoman period

In 1645, the Ottoman Empire began their campaign to conquer Crete. In the spring of 1648, they controlled the major part of the island, with the exception of Heraklion, Gramvousa, Spinalonga and Suda, which remained under Venetian rule.

After the capture of Rethymno in 1648, the Ottomans pillaged the monastery. The monks and the hegumen Simon Halkiopoulos took refuge in the Vrontissi Monastery. They were allowed to return after having sworn allegiance to Hussein Pasha, who also gave them the right to ring the monastery's bell. The Arkadi Monastery therefore became the Çanlı Manastır (Monastery where the bell is rung in Turkish). A firman authorized the rebuilding of the destroyed monasteries according to their original plans, without changes. Arkadi benefited but abused its rights by adding new buildings.[9]

During the Ottoman Period, the monastery continued to prosper, which was shown in the writing of Joseph Pitton de Tournefort. For the traveller, Arkadi was the richest and most beautiful of the monasteries of Crete.[5] There were 100 monks that lived in the convent and 200 others that lived in the surrounding countryside. The monastery's territory extended north of the sea and to the east of Rethymno to the top of Mount Ida in the south. These lands allowed the monastery to support itself through agriculture.

Tournefort notes "400 measures of oil" produced each year, a figure which would have been doubled if the monastery did not give the inferior olives to charity. Tournefort also boasts of the monastery's cellars, which had at least 200 barrels, labelled with the name of the hegumen who blessed them each year with a prayer.[10] The wine made at Arkadi was well known.[Note 3] This wine was called Malvoisie and was named after a town close to Heraklion. Franz Wilhelm Sieber, during his time in the monastery, recalled the hegumen's cellar and attributed the making of the wine to an excellent grape raised in high altitude, but that it was not produced at Malvoisie.[11]

At the beginning of the 17th century, the monastery fell into decline. Sieber, who stopped there nearly a century after Tournefort and Pococke, left a less flattering description. By the time the German visited, the monastery only had eight priests and twelve monks. Farming continued, but the monastery had debts. He recalled the hegumen who often had to go to Rethymno in order to acquire funds to pay the bills.[11]

Sieber described the library of the monastery as rich in more than a thousand texts, including religious texts and those of Pindar, Petrarch, Virgil, Dante, Homer, Strabon, Thucydides and Diodore of Sicily. But the traveller mentioned their sad state, noting that he had never seen books in such bad condition and that it was impossible to distinguish the works of Aristophanes from those of Euripedes.[11]

In 1822, a group of Turkish soldiers led by a Getimalis (Yetim Ali) took hold of Arkadi and pillaged it. The civilians of Amari gathered to plan how to retake the monastery and expel Getimalis and his troops.

Another version tells of a certain Anthony Melidonos, a Sphakian from Asia Minor, who came to the island at the head of a group of Greek volunteers from Asia Minor in order to support the Cretan efforts in the War of Greek Independence. With 700 troops, he set out across the island from west to east. After the pillaging of the monastery, he changed his course and went to Arkadi instead. Arriving in the night, his troops scaled the walls of the building and fired the monastery. He jumped on Getimalis who was drinking, grabbed him and threw him to the ground outside the room. He was about to kill Getimalis when Getimalis claimed to be at the point of converting to Christianity. A baptism immediately took place and the new convert was allowed to go free.[12]

Turkish and Greek documents mention the capacity of the monastery to produce enough food for the residents of the region and to hide fugitives from the Turkish authorities. The monastery also provided education for the local Christian population. From 1833 to 1840, the monastery invested 700 Turkish piastres in the schools in the region.[13]

Cretan Revolt of 1866

Context

By the mid-19th century, the Ottomans had occupied Crete for more than two centuries, despite frequent bloody uprisings by Cretan rebels. While the Cretans were rising against the Ottoman occupation during the War of Greek Independence, the London Protocol of 1830 dictated that the island could not be a part of the new Greek state.

On 30 March 1856, the Treaty of Paris obligated the Sultan to apply the Hatti-Houmayoun, which guaranteed civil and religious equality to Christians and Muslims.[14] The Ottoman authorities in Crete were reluctant to implement any reform.[15] Before the majority of Muslim conversions (the majority of the former Christians had converted to Islam and then recanted), the Empire tried to recant on liberty of conscience.[14] The institution of new taxes and a curfew also added to the discontent. In April 1858, 5,000 Cretans met at Boutsounaria. Finally an imperial decree on July 7, 1858 guaranteed them privileges in religious, judicial and financial matters. One of the major motivations of the revolt of 1866 was the breech of the Hatti-Houmayoun.[16]

A second cause of the insurrection of 1866 was the interference of Isma'il Pasha in an internal quarrel about the organization of the Cretan monasteries.[17] Several laymen recommended that the goods of the monasteries come under the control of a council of elders and that they be used to create schools, but they were opposed by the bishops. Isma'il Pasha intervened and designated several people to decide the subject and annulled the election of "undesirable" members, imprisoning the members of the committee that had been charged with going to Constantinople for presenting the subject to the Patriarch. This intervention provoked violent reactions from the Christian population of Crete.[17]

In the spring of 1866, meetings took place in several villages. On May 14, an assembly was held in the Aghia Kyriaki monstary in Boutsounaria near Chania. They sent a petition to the Sultan and the consuls of the big powers in Chania.[18] At the time of the first meetings of the revolutionary committees, the representatives were elected by province and the representative of the Rethymno region was the hegumen of Arkadi, Gabriel Marinakis.

At the announcement of these nominations Isma'il Pasha sent a message to the hegumen via the Bishop of Rethymno, Kallinikos Nikoletakis. The letter demanded that the hegumen dissemble the revolutionary assembly or the monastery would be destroyed by Ottoman troops. In the month of July 1866, Isma'il Pasha sent his army to capture the insurgents, but the members of the committee fled before his troops arrived. The Turks left again after destroying icons and other sacred objects that they found in the monastery.[19]

In September, Isma'il Pasha sent the hegumen a new threat of destroying the monastery if the assembly did not yield. The assembly decided to implement a system of defense for the monastery.[20] On September 24, Panos Koronaios arrived in Crete and landed at Bali. He marched to Arkadi, where he was made commander-in-chief of the revolt for the Rethymno region. A career military man, Koronaios believed that the monastery was not defensible. The hegumen and the monks disagreed and Koronaios conceded to them, but advised the destruction of the stables so that they could not be used by the Turks. This plan was ignored. After having named Ioannis Dimakopoulos to the post of commander of the garrison of the monastery, Koronaios left.[21] At his departure, numerous local residents, mostly women and children, took refuge in the monastery, bringing their valuables in hopes of saving them from the Turks. By 7 November 1866, the monastery sheltered 964 people: 325 men, of which 259 were armed, the rest women and children.[22]

Arrival of the Ottomans

Since the mid-October victory of Mustafa Pasha's troops at Vafes, the majority of the Turkish army was stationed in Apokoronas and were particularly concentrated in the fortresses around the bay of Souda. The monastery refused to surrender, so Mustafa Pasha marched his troops on Arkadi. First, he stopped and sacked the village of Episkopi.[23] From Episkopi, Mustafa sent a new letter to the revolutionary committee at Arkadi, ordering them to surrender and informing them that he would arrive at the monastery in the following days. The Ottoman army then turned toward Roustika, where Mustafa spent the night in the monastery of the prophet Elie, while his army camped in the villages of Roustika and Aghios Konstantinos. Mustafa arrived in Rethymno on 5 November where he met Turkish and Egyptian reinforcements. The Ottoman troops reached the monastery during the night of November 7-November 8. Mustafa, although he had accompanied his troops to a site relatively close, camped with his staff in the village of Messi.[24]

Attack

On the morning of 8 November, an army of 15,000 Ottomans and 30 cannons, directed by Suleyman, arrived on the hills of the monastery while Mustafa Pasha waited in the Messi. Suleyman, positioned on the hill of Kore.[Note 4] to the north of the monastery sent a last request for surrender. He received only gunfire in response.[22]

The assault was begun by the Ottomans. Their primary objective was the main door of the monastery on the western face. The battle lasted all day without the Ottomans infiltrating the building. The asseiged had barricaded the door and, from the beginning, taking it would be difficult.[25] The Cretans were relatively protected by the walls of the monastery, while the Ottomans, vulnerable to the insurgents' gunfire, suffered numerous losses. Seven Cretans took their position within the windmill of the monastery. This building was quickly captured by the Ottomans, who set it on fire, killing the Cretan warriors inside.[26]

The battle stopped with nightfall. The Ottomans received two heavy cannons from Rethymno, one which was called Koutsahila. They placed them in the stables. On the side of the insurgents, a war council decided to ask for help from Panos Koronaios and other Cretan leaders in Amari. Two Cretans left by way of the windows by ropes and, disguised as Turks, crossed the Ottoman lines.[27] The messengers returned later in the night with the news that it was now impossible for reinforcements to arrive in time because all of the access roads had been blocked by the Ottomans.[26]

Combat began again in the evening of November 9. The cannons destroyed the doors and the Turks made it into the building, where they suffered more serious losses. At the same time, the Cretans were running out of ammunition and many among them were forced to battle with only bayonets or other sharp objects. The Turks had the advantage.[28]

Destruction

The women and children inside the monastery were hiding in the powder room. The last Cretan fighters were finally defeated and hid within the monastery. Thirty-six insurgents found refuge in the refectory, near the ammunitions. Discovered by the Ottomans, who forced the door, they were massacred.[29]

In the powder room, where the majority of the women and children hid, Konstantinos Giaboudakis gathered the people hiding in the neighbouring rooms together. When the Turks arrived at the door of the powder room, Giaboudakis set the barrels of powder on fire and the resulting explosion resulted in numerous Turkish deaths.[29]

In another room of the monastery holding an equal number of powder barrels, insurgents made the same gesture. But the powder was humid and only exploded partially, so it only destroyed part of the northwest wall of the room.

Of the 964 people present at the start of the assault, 846 were killed in combat or at the moment of the explosion. 114 men and women were captured, but three or four managed to escape, including one of the messengers who had gone for reinforcements. The hegumen Gabriel was among the victims. Tradition holds that he was among those killed by the explosion of the barrels of powder, but it is more likely that he was killed on the first day of combat.[30] Turkish losses were estimated at 1500. Their bodies were buried without memorials and some were thrown in the neighboring gorges.[31] The remains of numerous Cretan Christians were collected and placed in the windmill, which was made into a reliquary in homage to the defenders of Arkadi. Among the Ottoman troops, a group of Coptic Egyptians were found on the hills outside the monastery. These Christians had refused to kill other Christians. They were executed by the Ottoman troops, and their ammunition cases left behind.[30]

114 survivors were taken prisoner and transported to Rethymno where they were subjected to numerous humiliations from the officers responsible for their transport, but also by the Muslim population who arrived to throw stones and insults when they entered the city.[31] The women and children were imprisoned for a week in the church of the Presentation of the Virgin. The men were imprisoned for a year in difficult conditions. The Russian consulate had to intervene to require Mustafa Pasha to keep basic hygienic conditions and provide clothing to the prisoners.[32] After one year, the prisoners were released.

-

Konstantinos Giaboudakis preparing the powder barrels

-

The explosion of the powder room

-

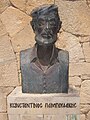

Konstantinos Giaboudakis

International reaction

The Ottomans considered taking Arkadi a big victory and celebrated it with cannon fire.[32] However, the events at Arkadi provoked indignation among the Cretans, but also in Greece and the rest of the world. The tragedy of Arkadi turned world opinion on the conflict. The event recalled the Third Siege of Missolonghi and the numerous Philhellenists of the world were in favor of Crete. Volunteers from Serbia, Hungary and Italy arrived on the island. Gustave Glourens, a teacher at the Collège de France, enlisted and arrived in Crete by the end of 1866. He formed a small group of philhellenists with three other Frenchmen, an Englishman, an American, an Italian and a Hungarian. This group published a brochure on The question of the Orient and the Cretan Renaissance, contacted French politicians and organized conferences in France and in Athens. The Cretans named him a deputy at the assembly, but he turned the position down.[33]

Giuseppe Garibaldi, in his letters, praised the patriotism of the Cretans and their wish to gain their independence. Numerous Garibaldians, moved by an ardent philhellenism, came to Crete and participated in several battles.[34] Letters written by Victor Hugo were published in the newspaper Kleio in Trieste, which contributed to the worldwide reaction. The letters gave encouragement to the Cretans and told them that their cause would succeed. He emphasized that the drama of Arkadi was no different than the Destruction of Psara and the Third Siege of Missolonghi. He described the tragedy of Arkadi:

In writing these lines, I am obeying an order from on high; an order that comes from agony.

[...]

One knows this word, Arkadian, but one hardly understands what it means. And here are some of the precise details that have been neglected. In Arkadia, the monastery on Mount Ida, founded by Heraclius, six thousand Turks attacked one hundred ninety-seven men and three hundred forty-three women and also children. The Turks had twenty-six cannons and two howitzers, the Greeks had two hundred forty rifles. The battle lasted two days and two nights; the convent had twelve hundred holes found in it from cannon fire; one wall crumbled, the Turks entered, the Greeks continued the fight, one hundred fifty rifles were down and out and yet the struggle continued for another six hours in the cells and the stairways, and at the end there were two thousand corpses in the courtyard. Finally the last resistance was broken through; the masses of the Turks took the convent. There only remained one barricaded room that held the powder and, in this room, next to the altar, at the center of a group of children and mothers, a man of eighty years, a priest, the hegumen Gabriel, in prayer...the door, battered by axes, gave and fell. The old man put a candle on the altar, took a look at the children and the women and lit the powder and spared them. A terrible intervention, the explosion, rescued the defeated...and this heroic monastery, that had been defended like a fortress, ended like a volcano.[35]

Not finding the necessary solution from the big European powers, the Cretans sought aid from the United States. At this time, the Americans tried to establish a presence in the Mediterranean and showed support for Crete. The relationship grew as they looked for a port in the Mediterranean and they thought, among others, to buy the island of Milo or Port Island.[36] The American public was sympathetic. The American philhellenes arrived to advocate for the idea of Cretan independence,[37] and in 1868, a question of recognition of independent Crete was addressed in the House of Representatives,[38] but it was decided by a vote to follow a policy of non-intervention in Ottoman affairs.[39]

Architecture

Walls and doors

The surrounding wall of the monastery forms a nearly rectangular quadrangle and surrounds an area of 5200 m². The feeling of a fortress is reinforced by the embrasures that are on the top part of the west wall and on the southern and eastern façades. Additionally, the width of the outside eastern wall is 1.20 meters.[40]

Inside the walls are buildings such as the hegumen's house, the monks' cells, the refectory, the stockrooms, the powder magazine and the hospice.[4]

The monastery has two main doors : one to the west and one on the east of the building. Entree could also be made through smaller doors: one in the south-west, two to the north and one last on the western façade.

The main door of the monastery is on the western façade of the surrounding wall. This door is called Rethemniotiki or Haniotiki, after its orientation towards those two towns. The original door was built in 1693, by the hegumen Neophytos Drossas. A manuscript at the monastery describes the original door, which was destroyed in 1866 during the Turkish assault. Made of square stones, there were two windows, decorated with pyramid-shaped pediments and framed by ribbed columns that were decorated with lions. On the pediment, there was an inscription that read:

"Lord, watch over the spirit of your servant, the Hegumen Neophytos Drossas, and of all our Christian brothers."[Note 5]

The current door was built in 1870. The general form of the former door was conserved, with two windows at level, framed by two columns. But the inscription honoring the hegumen Drossas, the lions and the pediments were not rebuilt.

On the eastern façade of the wall is the second door to the monastery. Facing Heraklion, the door is named Kastrini, after Kastro. As with the western door, the original door was destroyed in 1866 and was rebuilt in 1870.[41]

Church

The church is a basilica with two naves; the northern nave is dedicated to the Transfiguration of Christ and the southern nave is dedicated to Saint Constantine and Saint Helen. Saint Helen stands at the center and slightly to the south of the monastery. According to the inscription engraved on the face of the clock, the church was founded in 1587 by Klimis Hortatsis. The architecture of the building is heavily influenced by Renaissance art, as the church was built in the period in which Crete was a colony of the Republic of Venice.

In the smaller part of the front of the church, constructed by square blocks of regular brickwork, the primary element is four pairs of Corinthian columns. While there is a classically antique influence, the columns themselves, placed on elevated pedestals, are Gothic.[42][10] Between each pair of columns, there is an archway. The two arches at the ends of the facade support a door and a circular opening, decorated by palm leaves on the circumference.[43] The archway in the center of the façade is plain.

On the higher part of the façade, above the columns, there is a series of molding and elliptical openings, which are also decorated in palm leaves around the perimeter. The clock is at the centre and, at each end, there are Gothic obelisks.[43] Comparisons of the façade of the monastery with the work of Italian architects Sebastinao Serlio and Andrea Palladio suggests that the architect of the church was probably inspired by them.[43]

In 1645, the church was damaged by looters who destroyed the altar.[44] Long before the capture of the monastery by the Turks in 1866, the church was torched and the icons entirely destroyed. Only a cross, two wooden angels and a passage of the resurrection of Christ were saved from the flames. The apses of the church were also destroyed.

The current iconostase, in cypress, was erected in 1902. From 1924 to 1927, at the initiative of the archbishop Timotheos Veneris, the work of strengthening and restoration of the apses and the clock were begun.[44][45] The tiles on the interior of the building were totally replaced in 1933.[45]

Powder magazine

Before 1866, the powder magazine was in the southern part of the interior.[46] Slightly before the Turkish attack, and in fear that it could easily be broken into and the monastery blown up, the munitions were moved to the cellar, which was situated approximately 75 centimetres below where it had been originally placed, which was more secure.[46] The powder magazine is an oblong vaulted building. It is 21 metres long and 5.4 metres wide and was destroyed entirely during an explosion in 1866, with the exception of a small part of the vault in the western part of the room.[47]

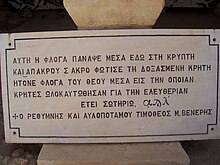

In 1930, the archbishop Timotheos Veneris placed a commemorative inscription which was fit in the eastern wall in remembrance of the events of 1866. The inscription reads:

The flame which lights the depths of this crypt

was a godly flame in which

the Cretans perished for freedom[Note 6]

The refectory

The refectory, the place where the monks took their meals, is located in the northern aisle of the monastery. It was built in 1687, which is mentioned in the inscription located below the door leading into courtyard of the refectory. On this inscription,[Note 7] one can read the name of Neophytos Drossas.[48]

From this courtyard, one can reach the hegumen's home by a staircase and the refectory. Above the door to the refectory, there is an inscription engraved in the lintel of the door in the honor of the virgin Mary and a hegumen preceding Neophytos Drossas.[Note 8] The refectory is a rectangular room of 18.10 meters long and 4.80 meters wide. It is covered by a vault. The eastern part holds the kitchens.

This building, which has not changed since its construction in 1687,[48] is the place where the last fighting in the assault of 1866 took place. One can still see the traces of bullets and swords in the wood of the tables and chairs.[49]

The hospice

The northwestern part of the monastery holds a hospice. Before 1866, this place held the hegumen's home, which was completely destroyed in the battle. It was a two-story building, the ground floor of which held kitchens and a dining room. From the dining room, a staircase led to a big room called the Synode room and was where the monks gathered after services.[50]

After 1866, the house was left in ruins for a number of years due to a lack of funds to rebuild. Near the end of the 19th century, the hegumen Gabriel Manaris visited several cities in Russia to try to raise funds to reconstruct the building. He collected money, sacred urns and priestly clothing. In 1904, under the direction of the bishop of Rethymno, Dionyssios, the house was cleared and replaced with a hospice, which was finished in 1906.

The stables

Outside the monastery, approximately 50 metres from the western door, are located the former stables of the monastery. They were constructed in 1714 by the hegumen Neophytos Drossas, which can be seen from the inscription over the door.[Note 9]

The building is 23.9 metres long and 17.2 metres wide. It is divided into three sections, each 4.3 metres. The internal and external walls are 1 metre wide. A staircase leads to the roof. The building sheltered the monastery's animals, but also was a room for the farm laborers.[51] Traces of the battle in 1866 are still visible, particularly on the staircase and the window jambs on the eastern wall.[52]

Memorial of the dead

Outside the monastery, about sixty metres to the west, there is a structure commemorating the sacrifice of the Cretans who died in 1866. This memorial, situated on the plateau that the monastery is located on, dominates the gorges.

The remains of the dead from the 1866 siege are stored in a glazed shelf. These bones clearly show battle scars and are pierced by bullets and swordcuts.[53] An inscription commemorates the sacrifice of the fallen Cretans:

Nothing is more noble or glorious than dying for one's country.

Of an octagonal shape, this structure is the former windmill which was later transformed into a storage room.[51] It served as a boneyard for a short time after the siege and acquired its current shape in 1910 at the initiative of Dionyssios, then the bishop of Rethymnon.[51]

35°18′36.27″N 24°37′46.11″E / 35.3100750°N 24.6294750°E

Notes

- ^ Version by Pococke and Sieber.

- ^ " ΑΡΚΑΔΙ(ΟΝ) ΚΕΚΛΗΜΑΙ /ΝΑΟΝ ΗΔ ΕΧΩ / ΚΟΝΣΤΑΝΤΙΝΟΥ ΑΝΑΚΤΟΣ / ΙΣΑΠΟΣΤΟΥΛΟΥ "

- ^ According to Robert Pashley, the Cretans drank the Arkadi wine on special occasions.

- ^ The summit of the hill is approximately 500 metres to the north of the monastery.

- ^ ΜΝΗΣΘΗΤΙ ΚΕ ΤΗΣ ΨΥΧΗΣ ΤΟΥ ΔΟΥΛΟΥ ΣΟΥ ΝΕΟΦΥΤΟΥ ΙΕΡΜΟΝΑΧΟΥ ΚΑΙ ΚΑΘΗΓΟΥΜΕΝΟΥ ΚΑΙ ΠΑΣΗΣ ΤΗΣ ΕΝ ΧΡΙΣΤΩ ΗΜΩΝ ΑΔΕΛΦΟΤΟΣ, in Provatakis (1980), p. 17

- ^ Αυτή η φλόγα π' άναψε μέσα εδώ στη κρύπτη κι απάκρου σ' άκρο φώτισε τη δοξασμένη Κρήτη, ήτανε φλόγα του Θεού μέσα εις την οποία Κρήτες ολοκαυτώθηκαν για την Ελευθερία

- ^ ΑΧΠΖ / ΝΦΤ / ΔΡC (abbreviations for 1687 Néophytos Drossas)

- ^ ΠΑΜΜΕΓΑ ΜΟΧΘΟΝ ΔΕΞΑΙΟ ΒΛΑΣΤΟΥ ΗΓΕΜΌΝΟΙΟ / ΔΕΣΠΟΙΝΑ Ω ΜΑΡΙΑ ΦΙΛΤΡΟΝ ΑΠΕΙΡΕΣΙΟΝ ΑΧΟ (Virgin Mary, accept the labor and the infinite devotion of the hegumen Vlastos 1670)

- ^ ΑΨΙΔ / ΜΑΙΟΥ Η / ΝΕΟΦΥ / ΤΟ ΔΡΣ (1714, May 8, Néophytos Drossas)

References

- ^ Detorakis (1988), p. 397

- ^ R. Pococke, Travels in the Orient, in Egypt, Arabia, Palestine, Syria, Greece, p. 187.

- ^ Kalogeraki (2002), p. 10

- ^ a b Kalogeraki (2002), p. 40

- ^ a b J. Pitton de Tournefort, Telling of Travels to the Levant, p. 19.

- ^ Robert Pashley (1837), Travels in Crete, London, p. 231.

- ^ Kalogeraki (2002), p. 17

- ^ a b Provatakis (1980), p. 12

- ^ a b Kalogeraki (2002), p. 18

- ^ a b J. Pitton de Tournefort, Telling of Travels to the Levant, p. 20.

- ^ a b c F.X. Sieber, Travels in the island of Crete in the year 1817

- ^ Thomas Keightley, History of the war of Independence in Greece

- ^ Provatakis (1980), p. 13

- ^ a b J. Tulard, Histoire de la Crète, p. 114.

- ^ Detorakis (1988), p. 328

- ^ Detorakis (1988), p. 329

- ^ a b Detorakis (1988), p. 330

- ^ Detorakis (1988), p. 331

- ^ Provatakis (1980), pp. 65–66

- ^ Provatakis (1980), p. 66

- ^ Provatakis (1980), p. 67

- ^ a b Provatakis (1980), p. 68

- ^ Kalogeraki (2002), p. 23

- ^ Kalogeraki (2002), p. 24

- ^ Kalogeraki (2002), p. 27

- ^ a b Kalogeraki (2002), p. 28

- ^ Provatakis (1980), p. 70

- ^ Provatakis (1980), p. 71

- ^ a b Provatakis (1980), p. 75

- ^ a b Provatakis (1980), p. 76

- ^ a b Kalogeraki (2002), p. 32

- ^ a b Kalogeraki (2002), p. 33

- ^ Dalègre (2002), p. 196

- ^ Kalogeraki (2002), p. 36

- ^ V. Hugo, Correspondance, t. 3, 1867

- ^ May (1944), p. 286

- ^ May (1944), pp. 290–291

- ^ May (1944), p. 292

- ^ May (1944), p. 293

- ^ Provatakis (1980), p. 16

- ^ Kalogeraki (2002), p. 44

- ^ Kalogeraki (2002), p. 45

- ^ a b c Kalogeraki (2002), p. 46

- ^ a b Provatakis (1980), p. 35

- ^ a b Kalogeraki (2002), p. 47

- ^ a b Provatakis (1980), p. 24

- ^ Kalogeraki (2002), p. 51

- ^ a b Kalogeraki (2002), p. 49

- ^ Kalogeraki (2002), p. 50

- ^ Kalogeraki (2002), p. 52

- ^ a b c Kalogeraki (2002), p. 53

- ^ Provatakis (1980), p. 28

- ^ Provatakis (1980), p. 25

Sources

- Dalègre, Joëlle (2002). Grecs et Ottomans, 1453–1923: de la chute de Constantinople à la disparition de l'empire ottoman (in French). l'Harmattan. ISBN 2747521621.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Detorakis, Theocharis (1988). "Η Τουρκοκρατία στην Κρήτη" [Turkish rule in Crete]. In Nikolaos M. Panagiotakis (ed.). Crete, History and Civilization (in Greek). Vol. II. Vikelea Library, Association of Regional Associations of Regional Municipalities. pp. 333–436.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kalogeraki, Stella (2002). Arkadi. Rethymnon: Mediterraneo Editions.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - May, Arthur J. (1944). "Crete and the United States, 1866–1869". Journal of Modern History. 16 (4): 286–293. JSTOR 1871034.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Provatakis, Theocharis (1980). Monastery of Arkadi. Athens: Toubi's.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

Media related to Moni Arkadiou at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Moni Arkadiou at Wikimedia Commons