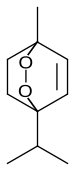

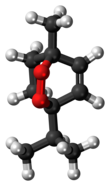

Ascaridole

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

1-Methyl-4-(1-methylethyl)-2,3-dioxabicyclo[2.2.2]oct-5-ene

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.408 | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties[1] | |||

| C10H16O2 | |||

| Molar mass | 168.23 g/mol | ||

| Appearance | Colorless liquid | ||

| Density | 1.010 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | 3.3 °C (37.9 °F; 276.4 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 40 °C (104 °F; 313 K) at 0.2 mmHg | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Ascaridole is a natural organic compound classified as a bicyclic monoterpene that has an unusual bridging peroxide functional group. It is a colorless liquid with a pungent smell and taste that is soluble in most organic solvents. Like other low molecular weight organic peroxides, it is unstable and prone to explosion when heated or treated with organic acids. Ascaridole determines the specific flavor of the Chilean tree boldo and is a major constituent of the oil of Mexican tea (wormseed). It is a component of natural medicine, tonic drinks and food flavoring in Latin American cuisine. As part of the oil, ascaridole is used as an anthelmintic drug that expels parasitic worms from plants, domestic animals and the human body.

History

Ascaridole was the first, and for a long time only, discovered naturally-occurring organic peroxide. It was isolated from Chenopodium oil and named by Hüthig in 1908, who described its explosive character and determined its chemical formula as C10H16O2. Hüthig also noted the indifference of ascaridole to aldehydes, ketones or phenols that characterized it as non-alcohol. When reacted with sulfuric acid, or reduced with zinc powder and acetic acid, ascaridole formed cymene.[2][3] These results were confirmed in a detailed study by E. K. Nelson in 1911, in particular that ascaridole explodes upon heating, reacting with sulfuric, hydrochloric, nitric, or phosphoric acids. Nelson showed that the new substance contained neither a hydroxyl nor a carbonyl group and that upon oxidation with iron sulfate it formed a glycol, now known as ascaridole glycol, C10H18O3. The glycol is more stable than ascaridole and has a higher melting point of about 64 °C, boiling point of 272 °C, and density of 1.098 g/cm3. Nelson also predicted the chemical structure of ascaridole which was almost correct, but had the peroxide bridge not along the molecular axis, but between the other, off-axis carbon atoms.[4] This structure was corrected by Otto Wallach in 1912.[5][6][7]

The first laboratory synthesis was demonstrated in 1944 by Günther Schenck and Karl Ziegler and might be regarded as mimicking the natural production of ascaridole. The process starts from α-terpinene which reacts with oxygen under the influence of chlorophyll and light. Under these conditions singlet oxygen is generated which reacts in a Diels–Alder reaction with the diene system in the terpinene.[7][8][9] Since 1945, this reaction has been adopted into the industry for large-scale production of ascaridole in Germany. It was then used as an inexpensive drug against intestinal worms.[10]

Properties

Ascaridole is a colorless liquid that is soluble in most organic solvents. It is toxic and has a pungent, unpleasant smell and taste. Like other pure, low molecular weight organic peroxides, it is unstable and prone to explosion when heated to a temperature above 130 °C or treated with organic acids. When heated, it emits fumes which are poisonous and possibly carcinogenic.[1][5][11] Ascaridole (organic peroxide) is forbidden to be shipped as listed in the US Department of Transportation Hazardous Materials Table 49 CFR 172.101.

Occurrence

The specific flavor of the Chilean tree boldo (Peumus boldus) primarily originates from ascaridole. Ascaridole is also a major component of epazote (or Mexican tea, Dysphania ambrosioides, formerly Chenopodium ambrosioides)[12][13] where it typically constitutes between 16 and 70% of the plant's essential oil.[14][15] The content of ascaridole in the plant depends on cultivation and is maximal when the nitrogen to phosphorus ratio in the soil is about 1:4. It also changes through the year peaking around the time when the plant seeds become mature.[16]

Applications

Ascaridole is mainly used as an anthelmintic drug that expels parasitic worms (helminths) from body and plants. This property gave the name to this chemical, after Ascaris – a genus of the large intestinal roundworms. In the early 1900s, it was a major remedy against intestinal parasites in humans, cats, dogs, goats, sheep, chickens, horses, and pigs, and it is still used in livestock, particularly in the Central American countries. The dosage was specified by the ascaridole content in the oil, which was traditionally determined with an assay developed by Nelson in 1920. It was later substituted with modern gas chromatography and mass spectrometry methods.[17] The worms and their larvae were killed by immersion in a solution of ascaridole in water (about 0.015 vol%) for 18 hours at 50 °F (10 °C) or 12 hours at 60 °F (16 °C) or 6 hours at 65 to 70 °F (18 to 21 °C). Meanwhile, such immersion did not damage the roots and stems of plants such as Iris, Phlox, Sedum and others at 70 °F (21 °C) for 15 hours or longer.[11]

The wormseed plant itself (Mexican tea) is traditionally used in Mexican cuisine for flavoring dishes and preventing flatulence from bean-containing food.[15] It is also part of tonic drinks and infusions to expel intestinal parasites and treat asthma, arthritis, dysentery, stomach ache, malaria, and nervous diseases in folk medicine practiced in North and South America, China, and Turkey.[16][17]

Health issues

The usage of wormseed oil on humans is limited by the toxicity of ascaridole and has therefore been discouraged. In high doses, wormseed oil causes irritation of skin and mucous membranes, nausea, vomiting, constipation, headache, vertigo, tinnitus, temporary deafness and blindness. Prolonged action induces depression of the central nervous system and delirium which transits into convulsions and coma. Long-term effects include pulmonary edema (fluid accumulation in the lungs), hematuria, and albuminuria (presence of red blood cells and proteins in the urine, respectively) and jaundice (yellowish pigmentation of the skin). Fatal doses of wormseed oil were reported as one teaspoon for a 14-month-old baby (at once) and daily administration of 1 mL over three weeks to a 2-year-old child. Ascaridole is also carcinogenic in rats.[15]

References

- ^ a b Lewis, R. J.; Lewis, R. J., Sr (2008). Hazardous Chemicals Desk Reference. Wiley-Interscience. p. 114. ISBN 0-470-18024-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schimmel's Report. April 1908. p. 108.

- ^ Arbuzov, Yu. A. (1965). "The Diels–Alder Reaction with Molecular Oxygen as Dienophile". Russ. Chem. Rev. 34 (8): 558. doi:10.1070/RC1965v034n08ABEH001512.

- ^ Nelson, E. K. (1911). "A Chemical Investigation of the Oil of Chenopodium". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 33 (8): 1404–1412. doi:10.1021/ja02221a016.

- ^ a b Wallach, O. (1912). "Zur Kenntnis der Terpene und der Ätherischen Öle" [Regarding Terpenes and Essential Oils]. Liebigs Ann. Chem. (in German). 392 (1): 49–75. doi:10.1002/jlac.19123920104.

- ^ Nelson, E. K. (1913). "A Chemical Investigation of the Oil of Chenopodium. II". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 35: 84–90. doi:10.1021/ja02190a009.

- ^ a b Nelson, E. K. "Chapter 5: Oxides: Ascaridole". The Terpenes. Vol. 2. CUP Archive. pp. 446–452.

- ^ Pape, M. (1975). "Industrial Applications of Photochemistry" (pdf). Pure Appl. Chem. 41 (4): 535–558. doi:10.1351/pac197541040535.

- ^ Schenck, G. O.; Ziegler, K. (April–June 1944). "Die Synthese des Ascaridols" [The Synthesis of Ascaridoles]. Naturwissenschaften (in German). 32 (14–26): 157. doi:10.1007/BF01467891. ISSN 0028-1042.

- ^ Brown, W. H.; Foote, C. S.; Iverson, B. L.; Anslyn, E. V. (2009). Organic Chemistry. Cengage Learning. p. 967. ISBN 0-495-38857-2.

- ^ a b US Department of Agriculture (1972). "Technical Bulletin". Technical Bulletin. 1441. US Department of Agriculture: 65.

- ^ Garro Alfaro, J. E. Plantas Competidoras: un componente más de los agroecosistemas. EUNED. p. 245. ISBN 9968-31-235-5.

- ^ Lang, A. L. A. (2003). Ecología Química. Plaza y Valdés. p. 323. ISBN 970-722-113-5.

- ^ Paget, H. (1938). "Chenopodium Oil. Part III. Ascaridole". J. Chem. Soc. 392 (1): 829–833. doi:10.1039/JR9380000829.

- ^ a b c Contis, E. T. (1998). "Some Toxic Culinary Herbs in North America". In Tucker, A. O.; Maciarella, M. J. (eds.). Food Flavors: Formation, Analysis, and Packaging Influences. Elsevier. pp. 408–409. ISBN 0-444-82590-8.

- ^ a b Small, E. (2006). Culinary Herbs. NRC Research Press. pp. 295–296. ISBN 0-660-19073-7.

- ^ a b "Chenopodium ambrosioides". Medicinal Plants for Livestock. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University, Department of Animal Science.