Australian megafauna

Australian megafauna is a term used to describe a number of comparatively large animal species in Australia. These species became extinct during the Pleistocene (20,000-50,000 years before present), but exact dates for their extinction have been lacking until recently.

The cause of the extinction is an active and contentious field of research. It is hypothesised that with the arrival of humans (around 48,000-60,000 years ago), hunting and the use of fire to manage their environment may have contributed to the extinction of the megafauna.[1] Increased aridity during peak glaciation (about 18,000 years ago) may have also contributed to the extinction of the megafauna. Some proponents claim climate change alone caused extinction of the megafauna, but these arguments do not account for the fact that megaufaunal species comfortably survived 2 million years of climatic oscillations, including a number of arid glacial periods, before their sudden extinction.

New evidence based on accurate optical luminescence and Uranium-thorium dating of megafaunal remains suggests that humans were the ultimate cause of the extinction of megafauna in Australia.[2] The dates derived show that all forms of megafauna became extinct in the same rapid timeframe — approximately 47,000 years ago — the period of time in which humans first arrived in Australia. The dates derived suggest the main mechanism for extinction was human burning of a then much less fire-adapted landscape; analysis of oxygen and carbon isotopes from teeth of megafauna indicate sudden, drastic, non-climate-related changes in vegetation and the diet of surviving marsupial species, as well as the loss of megafaunal species. Further analysis of oxygen and carbon isotopes from teeth of megafauna indicate the arid regional climates at the time of extinction were similar to arid regional climates of today, and that the megafauna were well adapted to arid climates.

Extinct Australian megafauna: pre-1788

The following is an incomplete list of Australian megafauna, in the format:

- Latin name, (common name, period alive), and a brief description.

Mammals

- Procoptodon goliath (the Giant Short-faced Kangaroo) is the largest kangaroo to have ever lived. It grew 2-3 metres (7-10 feet) tall, and weighed up to 230 kilograms. It had a flat shortened face with jaw and teeth adapted for chewing tough semi-arid vegetation, and forward-looking eyes providing stereoscopic vision. Procoptodon was one of seventeen species in three genera in the Sthenurine subfamily, all of which are extinct. Sthenurines inhabited open woodlands in central Northern Australia as the tropical rainforests were beginning to retreat. All sthenurines had an extremely developed, almost hoof-like, fourth toe on the hindlimbs, with other toes vestigial. Additionally, elastic ligaments between the toe bones gave this group improved spring and speed compared to modern kangaroos. Sthenurine forelimbs were long with two extra-long fingers and claws compared with the relatively small, stiff arms of modern macropods. These may have been used for pulling branches nearer for eating and for quadrupedal movement for short distances.

- Simosthenurus occidentalis (another Sthenurine) was about as tall as a modern Eastern Grey Kangaroo, but much more robust. It is one of the nine species of leaf-eating kangaroos identified in fossils found in the Naracoorte Caves National Park.

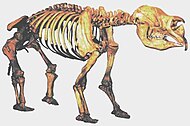

- Diprotodon optatum was the largest species of Diprotodontid. Approximately three metres long, two metres high at the shoulder and weighing up to two tonnes, it resembled a giant wombat. It is the largest marsupial currently known.

- Zygomaturus trilobus was a smaller (bullock-sized, about two metres long by one metre high) Diprotodontid that may have had a short trunk. It appears to have lived in wetlands, using two fork-like incisors to shovel up reeds and sedges for food.

- Palorchestes azael (the Marsupial Tapir) was a Diprotodontid of a similar size to Zygomaturus, with long claws and a longish trunk. It lived in the Miocene.

- Phascolarctos stirtoni was a koala similar to the modern form, but one third larger.

- Thylacoleo carnifex, (the Marsupial Lion), was the size of a leopard, and had a cat-like skull with large slicing pre-molars. It had a retractable thumb-claw and massive forelimbs. It was almost certainly carnivorous and a tree-dweller.

- Sarcophilus harrisii laniarius was a large form of the Tasmanian Devil.

- Zaglossus hacketti was a sheep-sized echidna uncovered in Mammoth Cave in Western Australia, and is the largest monotreme so far uncovered.

- Megalibgwilia ramsayi was a large, long-beaked echidna with powerful forelimbs for digging. Its diet would probably have included worms and grubs rather than ants.

- Propleopus oscillans (the Carnivorous Kangaroo), from the Miocene and Pliocene epochs, was a large (~70 kilogram) rat-kangaroo with large shearing and stout grinding teeth that indicate it may have been an opportunistic carnivore able to eat insects, vertebrates (possibly carrion), fruits, and soft leaves.

- Protemnodon a form of giant wallaby with 4 species.[3]

- Congruus congruus a wallaby from Naracoorte.

- Warrendja wakefieldi a wombat from Naracoorte.

Birds

- Family Dromornithidae: this group of birds was more closely related to waterfowl than modern ratites.

- Dromornis stirtoni, (Stirton's Thunder Bird, Miocene epoch) was a flightless bird three metres tall that weighed about 500 kilograms. It is one of the largest birds so far discovered. It inhabited subtropical open woodlands and may have been carnivorous. It was heavier than the Moa and taller than the Aepyornis.

- Bullockornis planei (the 'Demon Duck of Doom') was another huge member of the Dromornithidae. It was up to 2.5 metres tall and weighed up to 250 kilograms, and was probably carnivorous.

- Genyornis newtoni (the Mihirung) was related to Dromornis, and was about the height of an ostrich. It was the last survivor of the Dromornithidae. It had a large lower jaw and was probably omnivorous.

- Leipoa gallinacea (formerly Progura) was a giant malleefowl.

Reptiles

- Megalania prisca was a giant, carnivorous goanna-like lizard that might have grown to as long as seven metres, and weighed up to 1,940 kilograms (Molnar, 2004).

- Wonambi naracoortensis was a non-venomous snake of five to six metres in length, an ambush predator at waterholes which killed its prey by constriction.

- Quinkana sp., was a terrestrial crocodile which grew from five to possibly 7 metres in length. It had long legs positioned underneath its body, and chased down mammals, birds and other reptiles for food. Its teeth were blade-like for cutting rather than pointed for gripping as with water dwelling crocodiles. It belonged to the Mekosuchine subfamily (all now extinct). It was discovered at Bluff Downs in Queensland.

- Liasis sp., (Bluff Downs Giant Python), lived during the Pliocene epoch, grew up to ten metres long, and is the largest Australian snake known. It hunted mammals, birds and reptiles in riparian woodlands. It is most similar to the extant Olive Python (Liasis olivacea).[4]

References

- ^ Miller, G. H. 2005. Ecosystem Collapse in Pleistocene Australia and a Human Role in Megafaunal Extinction. Science, 309:287-290 PMID 16002615

- ^ Prideaux, G.J. et al. 2007. An arid-adapted middle Pleistocene vertebrate fauna from south-central Australia. Nature 445:422-425

- ^ Helgen, K.M., Wells, R.T., Kear, B.P., Gerdtz, W.R., and Flannery, T.F. (2006). Ecological and evolutionary significance of sizes of giant extinct kangaroos. Australian Journal of Zoology 54, 293–303. doi:10.1071/ZO05077

- ^ Scanlon JD and Mackness BS. 2001. A new giant python from the Pliocene Bluff Downs Local Fauna of northeastern Queensland. Alcheringa 25: 425-437

- Field, J. H. and J. Dodson. 1999. Late Pleistocene megafauna and archaeology from Cuddie Springs, south-eastern Australia. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 65: 1-27.

- Field, J. H. and W. E. Boles. 1998. Genyornis newtoni and Dromaius novaehollandiae at 30,000 b.p. in central northern New South Wales. Alcheringa 22: 177-188.

- Long, J.A., Archer, M. Flannery, T.F. & Hand, S. 2003. Prehistoric Mammals of Australia and New Guinea -100 Million Years of Evolution. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. 242pp.

- Molnar, R. 2004. Dragons in the Dust: The Paleobiology of the Giant Lizard Megalania. Indiana University Press. Page: 127.

- Murray, P. F. and D. Megirian. 1998. The skull of dromornithid birds: anatomical evidence for their relationship to Anseriformes (Dromornithidae, Anseriformes). Records of the South Australian Museum 31: 51-97.

- Roberts, R. G., T. F. Flannery, L. A. Ayliffe, H. Yoshida, J. M. Olley, G. J. Prideaux, G. M. Laslett, A. Baynes, M. A. Smith, R. Jones, and B. L. Smith. 2001. New ages for the last Australian megafauna: continent-wide extinction about 46,000 years ago. Science 292: 1888-1892.

- Wroe, S., J. Field, and R. Fullagar. 2002. Lost giants. Nature Australia 27(5): 54-61.