Battle of Ain Jalut

| Battle of Ain Jalut | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mongol raids into Palestine | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Mongol Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| Kitbuga † | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Light cavalry and horse archers, heavy cavalry, infantry, hand cannoneers | Mongol lancers and horse archers, 500 Cilician Armenian troops, Georgian contingent, local Ayyubid contingents | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown; most sources agree or at least note that it was probably numerically much larger than the Mongol force[2] | One Mongol detachment of about 10,000-12,000[1][2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Near complete | ||||||

|

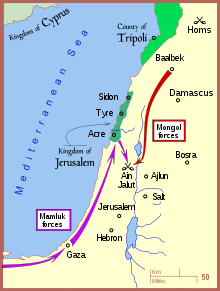

The Battle of Ain Jalut (Ayn Jalut, in Arabic: عين جالوت, the "Spring of Goliath", or Harod Spring, in Hebrew: מעין חרוד) took place on 3 September 1260 between Muslim Mamluks and the Mongols in the southeastern Galilee, in the Jezreel Valley, not far from the site of Zir'in. The battle marked the south-westernmost extent of Mongol conquests, and was the first time a Mongol advance had been permanently halted.[3] This was blamed on the sudden death of the then-Khagan Möngke Khan; an event that forced the Mongol Ilkhanate Hulagu Khan to take a large part of his army back with him on the way to Mongolia. This left Hulagu's lieutenant, Kitbuga, with only a small detachment of soldiers.

Preceding events

When Möngke Khan became Great Khan in 1251, he immediately set out to implement his grandfather Genghis Khan's plan for world empire. To lead the task of subduing the nations of the West, he selected his brother, another of Genghis Khan's grandsons, Hulagu Khan.[4]

Assembling the army took five years, and it was not until 1256 that Hulagu was prepared to begin the invasions. Operating from the Mongol base in Persia, Hulagu proceeded south. Möngke Khan had ordered good treatment for those who yielded without resistance, and destruction for those who did not. In this way Hulagu and his army had conquered some of the most powerful and longstanding dynasties of the time. Other countries in the Mongols' path submitted to Mongol authority, and contributed forces to the Mongol army. By the time that the Mongols reached Baghdad, their army included Cilician Armenians, and even some Frankish forces from the submissive Principality of Antioch. The Hashshashin in Persia fell, the 500-year-old Abbasid Caliphate of Baghdad was destroyed (see Battle of Baghdad), and so too fell the Ayyubid dynasty in Damascus. Hulagu's plan was to then proceed southwards through the Kingdom of Jerusalem towards the Mamluk Sultanate, to confront the major Islamic power.[4]

During the Mongol attack on the Mamluks in the Middle East, most of the Mamluks were Kipchaks, and the Golden Horde's supply of Kipchaks replenished the Mamluk armies and helped them fight off the Mongols.[5]

Mongol envoys to Egypt

In 1260, Hulagu sent envoys to Qutuz in Cairo, demanding his surrender:

From the King of Kings of the East and West, the Great Khan. To Qutuz the Mamluk, who fled to escape our swords. You should think of what happened to other countries and submit to us. You have heard how we have conquered a vast empire and have purified the earth of the disorders that tainted it. We have conquered vast areas, massacring all the people. You cannot escape from the terror of our armies. Where can you flee? What road will you use to escape us? Our horses are swift, our arrows sharp, our swords like thunderbolts, our hearts as hard as the mountains, our soldiers as numerous as the sand. Fortresses will not detain us, nor armies stop us. Your prayers to God will not avail against us. We are not moved by tears nor touched by lamentations. Only those who beg our protection will be safe. Hasten your reply before the fire of war is kindled. Resist and you will suffer the most terrible catastrophes. We will shatter your mosques and reveal the weakness of your God and then will kill your children and your old men together. At present you are the only enemy against whom we have to march.[6]

Qutuz responded, however, by killing the envoys and displaying their heads on Bab Zuweila, one of the gates of Cairo.[4]

The campaign

The power dynamic then changed due to the death of the Great Khan Möngke on an expedition to China, requiring Hulagu and other senior Mongols to return home to decide upon his successor. A potential Great Khan, Hulagu took the majority of his army with him, and left a much smaller force west of the Euphrates of only around one or two tumens (10,000–20,000 men, the size of a modern military division) under his best general, the Nestorian Christian Naiman Kitbuqa Noyan.[7]

Upon receiving news of Hulagu's departure, Mamluk Sultan Qutuz quickly assembled a large army at Cairo and invaded Palestine.[8] In late August, Kitbuqa's forces proceeded south from their base at Baalbek, passing to the east of Lake Tiberias into Lower Galilee.

The Mamluk Sultan Qutuz at that time allied with a fellow Mamluk, Baibars, who chose to ally himself with Qutuz in the face of a greater enemy, after the Mongols captured Damascus and most of Bilad al-Sham.[3]

The Mongols, for their part, attempted to form a Franco-Mongol alliance with (or at least demand the submission of) the remnant of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, now centered on Acre; but Pope Alexander IV had forbidden this. Tensions between Franks and Mongols had also increased when Julian of Sidon caused an incident which resulted in the death of one of Kitbuqa's grandsons. Angered, Kitbuqa sacked Sidon. The Barons of Acre and the remainder of the Crusader outposts, contacted by the Mongols, had also been approached by the Mamluks, seeking military assistance against the Mongols.[3]

Though the Mamluks were the traditional enemies of the Franks, the Barons of Acre recognized the Mongols as the more immediate menace, and so the Crusaders opted for a position of cautious neutrality between the two forces.[9] In an unusual move, they agreed that the Egyptian Mamluks could march north through the Crusader territories unmolested, and even camp to resupply near Acre. When news arrived that the Mongols had crossed the Jordan River, Sultan Qutuz and his forces proceeded southeast toward the spring at Ain Jalut in the Jezreel Valley.[10]

The battle

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2013) |

The first to advance were the Mongols, whose force also included troops from the Kingdom of Georgia and about 500 troops from the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, both of which had submitted to Mongol authority. The Mamluks had the advantage of knowledge of the terrain, and Qutuz capitalized on this by hiding the bulk of his force in the highlands, hoping to bait the Mongols with a smaller force under Baibars.

The two armies fought for many hours, with Baibars most of the time implementing hit-and-run tactics, in order to provoke the Mongol troops and at the same time preserve the bulk of his troops intact. When the Mongols carried out another heavy assault, Baibars – who it is said had laid out the overall strategy of the battle since he had spent much time in that region, earlier in his life, as a fugitive – and his men feigned a final retreat, drawing the Mongols into the highlands to be ambushed by the rest of the Mamluk forces concealed among the trees. The Mongol leader Kitbuqa, already provoked by the constant fleeing of Baibars and his troops, committed a grave mistake; instead of suspecting a trick, Kitbuqa decided to march forwards with all his troops on the trail of the fleeing Mamluks. When the Mongols reached the highlands, Mamluk forces emerged from hiding and began to fire arrows and attack with their cavalry. The Mongols then found themselves surrounded on all sides.

The Mongol army fought very fiercely and very aggressively to break out. Some distance away, Qutuz watched with his private legion. When Qutuz saw the left wing of the Mamluk army almost destroyed by the desperate Mongols seeking an escape route, Qutuz threw away his combat helmet, so that his warriors could recognize him. He was seen the next moment rushing fiercely towards the battlefield yelling "wa islamah!" ("Oh my Islam"), urging his army to keep firm, and advanced towards the weakened side, followed by his own unit. The Mongols were pushed back and fled to a vicinity of Bisan, followed by Qutuz's forces, but they managed to reorganize and return to the battlefield, making a successful counterattack. However, the battle shifted in favor of the Mamluks, who now had both the geographic and psychological advantage, and eventually some of the Mongols were forced to retreat. When the battle ended, the Mamluk heavy cavalrymen had accomplished what had never been done before, beating the Mongols in close combat.[10] Kitbuqa and almost the whole Mongol army that had remained in the region perished.

The Battle of Ain Jalut is also notable for being the earliest known battle where explosive hand cannons (midfa in Arabic) were used.[11] These explosives were employed by the Mamluk Egyptians in order to frighten the Mongol horses and cavalry and cause disorder in their ranks. The explosive gunpowder compositions of these cannons were later described in Arabic chemical and military manuals in the early 14th century.[12][13]

Aftermath

On the way back to Cairo after the victory at Ain Jalut, Qutuz was assassinated by several emirs in a conspiracy led by Baibars.[14] Baibars became the new Sultan. His successors would go on to capture the last of the Crusader states in The Holy Land by 1291.

Internecine conflict prevented Hulagu Khan from being able to bring his full power against the Mamluks to avenge the pivotal defeat at Ain Jalut. Berke Khan, the Khan of the Golden Horde to the north of Ilkhanate, had converted to Islam, and watched with horror as his cousin destroyed the Abbasid Caliph, the spiritual head of Islam. Muslim historian Rashid-al-Din Hamadani quoted Berke as sending the following message to Mongke Khan, protesting the attack on Baghdad (not knowing Mongke had died in China): "He (Hulagu) has sacked all the cities of the Muslims, and has brought about the death of the Caliph. With the help of God I will call him to account for so much innocent blood."[15] The Mamluks, learning through spies that Berke was both a Muslim and not fond of his cousin, were careful to nourish their ties to him and his Khanate.

After the Mongol succession was finally settled, with Kublai as the last Great Khan, Hulagu returned to his lands by 1262, and massed his armies to attack the Mamluks and avenge Ain Jalut. However, Berke Khan initiated a series of raids in force which lured Hulagu north, away from the Levant to meet him. Hulagu suffered severe defeat in an attempted invasion north of the Caucasus in 1263. This was the first open war between Mongols, and signaled the end of the unified empire.

Hulagu was able to send only a small army of two tumens in his sole attempt to attack the Mamluks after Ain Jalut, and it was repulsed. Hulagu Khan died in 1265 and was succeeded by his son Abaqa.

Battle of Ain Jalut in fiction

Robert Shea's historical novel The Saracen deals extensively with the Battle of Ain Jalut and the subsequent assassination of Sultan Qutuz.

Notes

- ^ a b Encyclopedia Grammatica

- ^ a b John, Simon (2014). Crusading and warfare in the Middle Ages : realities and representations. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781472407412.

- ^ a b c Tschanz, David W. "Saudi Aramco World : History's Hinge: 'Ain Jalut".

- ^ a b c Man, John (2006). Kublai Khan: From Xanadu to Superpower. London: Bantam. pp. 74–87. ISBN 978-0-553-81718-8.

- ^ Halperin, Charles J. 2000. “The Kipchak Connection: The Ilkhans, the Mamluks and Ayn Jalut”. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 63 (2). Cambridge University Press: 229–45. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1559539.

- ^ Tschanz, David W. "Saudi Aramco World : History's Hinge: 'Ain Jalut".

- ^ René Grousset (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Rutgers University Press. pp. 361 &, 363. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ^ p.424, 'The Collins Encyclopedia of Military History' (4th edition, 1993), Dupuy & Dupuy,

- ^ Morgan, p. 137.

- ^ a b Bartlett, p. 253

- ^ Islamic Focus: Hand Cannons. Islamic Focus.co.za, January 2015

- ^ Ahmad Y Hassan, Gunpowder Composition for Rockets and Cannon in Arabic Military Treatises In Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries Archived February 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ancient Discoveries, Episode 12: Machines of the East. History Channel. 2007. (Part 4 and Part 5)

- ^ Although medieval historians give conflicting accounts, modern historians assign responsibility for Qutuz's assassination to Baibars, as Baibars had been promised Syria as a reward for his efforts in Ain Jalut but when it was time to claim his prize, Qutuz commanded him to be patient. See Perry (p. 150), Amitai-Preiss (p. 47, "a conspiracy of amirs, which included Baybars and was probably under his leadership"), Holt et al. (Baibars "came to power with [the] regicide [of Qutuz] on his conscience"), and Tschanz. For further discussion, see article on "Qutuz".

- ^ The Mongol Warlords quotes Rashid al Din's record of Berke Khan's pronouncement; this quote is also found in Amitai-Preiss's The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War.

References

- Al-Maqrizi, Al Selouk Leme'refatt Dewall al-Melouk, Dar al-kotob, 1997.

- Bohn, Henry G. (1848) The Road to Knowledge of the Return of Kings, Chronicles of the Crusades, AMS Press, New York, 1969 edition, a translation of Chronicles of the Crusades : being contemporary narratives of the crusade of Richard Coeur de Lion by Richard of Devizes and Geoffrey de Vinsauf and of the crusade of St. Louis, by Lord John de Joinville.

- Amitai-Preiss, Reuven (1995). Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War, 1260–1281. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 978-0-521-46226-6.

- Bartlett, W. B. (1999). God Wills It! - An Illustrated History of the Crusades. Sutton Publishing Limited. ISBN 0-7509-1880-2.

- Eric H. Cline (2002). The Battles of Armageddon. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-06739-7.

- Robert Cowley; Geoffrey Parker (2001). The Reader's Companion to Military History. Houghton Mifflin. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-618-12742-9. Retrieved 2008-03-26.

- J. D. Fage; Roland Anthony Oliver (1975). The Cambridge History of Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20981-1.

- Grousset, René (1991), Histoire des Croisades, III, Editions Perrin, ISBN 2-262-02569-X.

- Hildinger, Erik. (1997). Warriors of the Steppe. Sarpedon Publishing. ISBN 0-306-81065-4

- Holt, P. M.; Lambton, Ann; Lewis, Bernard (1977) The Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. 1A: The Central Islamic Lands from Pre-Islamic Times to the First World War, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29135-4.

- Morgan, David (1990) The Mongols. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-17563-6

- Nicolle, David, (1998). The Mongol Warlords Brockhampton Press.

- Perry, Glenn E. (2004) The History of Egypt, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-313-32264-8.

- Reagan, Geoffry, (1992). The Guinness Book of Decisive Battles . Canopy Books, NY.

- Saunders, J. J. (1971) The History of the Mongol Conquests, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. ISBN 0-8122-1766-7

- Sicker, Martin (2000) The Islamic World in Ascendancy: From the Arab Conquests to the Siege of Vienna, Praeger Publishers.

- Soucek, Svatopluk (2000) A History of Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press.

- Tschanz, David W. (July–August 2007). "History's Hinge: 'Ain Jalut". Saudi Aramco World. Archived from the original on 12 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-24.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

- Battles involving the Mongols

- Medieval Israel

- Medieval Palestine

- Battles involving the Mamluk Sultanate (Cairo)

- Conflicts in 1260

- Battles involving the Kingdom of Georgia

- Battles involving the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia

- Egypt–Mongolia relations

- 1260 in the Mamluk Sultanate (Cairo)

- 1260 in the Kingdom of Georgia

- 1260 in the Mongol Empire