Battle of Fort Henry

| Battle of Fort Henry | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Bombardment and capture of Fort Henry, Tenn, by Currier and Ives. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Ulysses S. Grant Andrew H. Foote | Lloyd Tilghman (POW) | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

District of Cairo Western Flotilla |

Fort Henry garrison Fort Heiman garrison | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

15,000 7 ships[1] | 3,000–3,400[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 40[2] | 79[2] | ||||||

The Battle of Fort Henry was fought on February 6, 1862, in western Middle Tennessee, during the American Civil War. It was the first important victory for the Union and Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in the Western Theater.

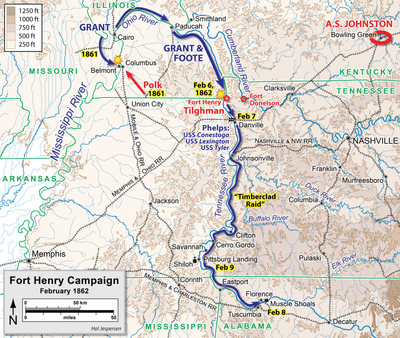

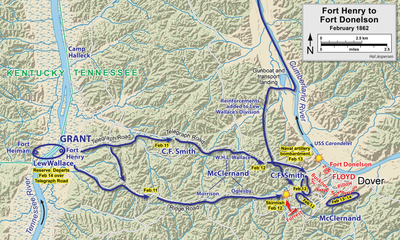

On February 4 and February 5, Grant landed two divisions just north of Fort Henry on the Tennessee River. (Although the name was not yet in use, the troops serving under Grant were the nucleus of the Union's successful Army of the Tennessee.[3]) His plan was to advance upon the fort on February 6 while it was being simultaneously attacked by United States Navy gunboats commanded by Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote. A combination of effective naval gunfire and the poor siting of the fort, almost completely inundated by rising river waters, caused its commander, Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman, to surrender to Foote before the Army arrived.

The surrender of Fort Henry opened the Tennessee River to Union traffic past the Alabama border, which was demonstrated by a "timberclad" raid of wooden ships from February 6 through February 12. They destroyed Confederate shipping and railroad bridges upriver. Grant's army proceeded overland 12 miles (19 km) to the Battle of Fort Donelson.

Background

In early 1861 the critical border state of Kentucky had declared neutrality in the American Civil War. This neutrality was first violated on September 3, when Confederate Brig. Gen. Gideon J. Pillow, acting on orders from Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk, occupied Columbus. Two days later Union Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, displaying the personal initiative that would characterize his later career, seized Paducah, a major transportation hub of rail and port facilities at the mouth of the Tennessee. Henceforth, neither adversary respected the proclaimed neutrality of the state and the Confederate advantage was lost; the buffer zone that Kentucky provided was no longer available to assist in the defense of Tennessee.[4]

By early 1862, on the Confederate side, a single general, Albert Sidney Johnston, commanded all forces from Arkansas to the Cumberland Gap. But his forces were spread too thinly over a wide defensive line: his left flank was Polk in Columbus with 12,000 men; his right flank was Brig. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner in Bowling Green, Kentucky, with 4,000; the center consisted of two forts under the command of Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman, also with 4,000. Fort Henry and Fort Donelson were the sole positions to defend the important Tennessee and Cumberland rivers, respectively. If these rivers were opened to Union military traffic, two direct invasion paths would lead into Tennessee and beyond.[5]

| Key commanders at the Battle of Fort Henry |

|---|

|

The Union military command in the West suffered from a lack of unified command, organized into three separate departments: the Department of Kansas, under Maj. Gen. David Hunter; the Department of Missouri, under Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck; and the Department of the Ohio, under Brig. Gen. Don Carlos Buell. By January 1862, this disunity of command was apparent because they could not agree on a strategy for operations in the Western theater. Buell, under political pressure to invade and hold pro-Union eastern Tennessee, moved slowly in the direction of Nashville. In Halleck's department, Grant demonstrated up the Tennessee River to divert attention from Buell's intended advance, which did not occur. Halleck and the other generals in the West were coming under political pressure from President Abraham Lincoln to participate in a general offensive by Washington's Birthday. Despite his traditional caution, Halleck eventually reacted positively to Grant's proposal that he move against Fort Henry. He hoped that this would improve his standing in relation to his rival, Buell. But he and Grant were also concerned about rumors that Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard would soon arrive in the theater with large numbers of reinforcements, so celerity was warranted. On January 30, 1862, Halleck authorized Grant to take Fort Henry.[6]

Grant wasted no time, leaving Cairo, Illinois, at the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, on February 2. His invasion force consisted of 15–17,000 men in two divisions, commanded by Brig. Gens. John A. McClernand and Charles F. Smith, and the Western Flotilla, commanded by United States Navy Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote. Foote had four ironclad gunboats (flagship USS Cincinnati, USS Carondelet, USS St. Louis, and USS Essex) under his direct command, and three wooden ("timberclad") gunboats (USS Conestoga, USS Tyler, and USS Lexington) under Lt. Seth Ledyard Phelps. There were insufficient transport ships this early in the war to deliver all of the army troops in a single operation, so two trips upriver were required to reach the fort.[1]

Fort Henry

Fort Henry was a five-sided, open-bastioned earthen structure covering 10 acres (0.04 km2) on the eastern bank of the Tennessee River, near Kirkman's Old Landing.[7] The site was about one mile above Panther Creek and about six miles below the mouth of the Sandy River and Standing Rock Creek.[8]

In May 1861, Isham G. Harris, the governor of Tennessee, appointed the state's attorney, Daniel S. Donelson, as a brigadier general and directed him to build fortifications on the rivers of Middle Tennessee. Donelson found suitable sites, but they were within the borders of Kentucky, then still neutral. Moving upriver to just inside the Tennessee border, he selected the site of the fort that would bear his name on the Cumberland River. Colonel Bushrod Johnson of the Tennessee Corps of Engineers approved of the site.[9]

As construction of Fort Donelson began, Donelson moved 12 miles (19 km) west to the Tennessee River and selected the site of Fort Henry, naming it after Tennessee Senator Gustavus Adolphus Henry Sr.. Since Fort Donelson was on the west bank of the Cumberland, he selected the east bank of the Tennessee for the second fort so that one garrison could travel between them and be used to defend both positions, which he deemed unlikely to be attacked simultaneously. Unlike its counterpart on the Cumberland, Fort Henry was situated on low, swampy ground, dominated by hills across the river. On the plus side, it had an unobstructed field of fire two miles (3 km) downriver. Donelson's surveying team—Adna Anderson, a civil engineer, and Maj. William F. Foster from the 1st Tennessee Infantry—objected strongly to the site and appealed to Colonel Johnson, who inexplicably approved it.[10]

The fort was designed to stop traffic on the river, not to withstand infantry assaults, certainly not at the scale that armies would achieve during the war. Construction began in mid-June, using men from the 10th Tennessee Infantry and slaves, and the first cannon was test fired on July 12, 1861. After this flurry of activity, however, the remainder of 1861 saw little more because forts on the Mississippi River had a higher priority for receiving men and artillery. In late December, additional men from the 27th Alabama Infantry arrived along with 500 slaves. They constructed a small fortification across the river on Stewart's Hill, within artillery range of Fort Henry, naming it Fort Heiman. At about the same time, Brig. Gen. Lloyd Tilghman assumed command of both Forts Henry and Donelson. At Fort Henry were approximately 3,000–3,400 men, two brigades commanded by Colonels Adolphus Heiman and Joseph Drake. They were armed primarily with antique flintlock rifles from the War of 1812.[11]

Seventeen guns were mounted in Fort Henry by the time of the battle, eleven covering the river and the other six positioned to defend against a land attack. There were two heavy guns, a 10-inch (250 mm) Columbiad and a 24-pounder rifled cannon, with the remainder being 32-pounder smoothbores. There were two 42-pounders, but no ammunition of that caliber was available. When the river was at normal levels, the walls of the fort rose 20 feet (6.1 m) about it and were 20 feet (6.1 m) thick at the base, sloping upward to about 10 feet (3.0 m) thick at the parapet. But in February 1862, heavy rains caused the river to rise and most of the fort was underwater, including the powder magazine.[12]

The Confederates deployed one additional defensive measure, which was then unique in the history of warfare: several torpedoes (in modern terminology, a naval minefield) were anchored below the surface in the main shipping channel, rigged to explode when touched by a passing ship. (This measure turned out to be ineffective, due to high water levels and the leaking metal containers of the torpedoes.)[13]

Battle

On February 4 and February 5, Grant landed his divisions in two different locations: McClernand's three miles (5 km) north on the east bank of the Tennessee River to prevent the garrison's escape and C.F. Smith's to occupy Fort Heiman on the Kentucky side, which would ensure the fort’s fall. But the battle turned on naval actions and concluded before the infantry saw action.[14]

Tilghman realized that it was only a matter of time before Fort Henry fell. Only nine guns remained above the water to mount a defense. While leaving artillery in the fort to hold off the Union fleet, he escorted the rest of his force out of the area and sent them off on the overland route to Fort Donelson, twelve miles (19 km) away. Fort Heiman was abandoned on February 4, and all but a handful of artillerymen left Fort Henry on February 5. (Union cavalry pursued the retreating Confederates, but the poor conditions of the roads prevented any serious confrontation and they took only a few captives.)[15]

Foote's seven gunboats began bombarding the fort on February 6. This was the first engagement for the Western Flotilla, using newly designed and hastily constructed ironclads. Foote deployed the four ironclads in a line abreast, followed by the three wooden ships, which held back for long-range, but less effective, fire against the fort. It was primarily the low elevation of Fort Henry's guns that allowed Foote's fleet to escape serious destruction; the Confederate fire was able to hit the ships only where their thin armor was strongest. One ship was seriously damaged, causing many casualties. A chance 32-pound shot penetrated USS Essex and hit her middle boiler, sending scalding steam throughout half of the ship. Thirty-two men were killed or wounded, including her commander, William D. Porter, and the ship was out of action for the remainder of the campaign.[16]

Aftermath and the timberclad raid

After the battle had lasted 75 minutes, Tilghman surrendered to the fleet, which had engaged the fort and closed within 400 yards (370 m). A small boat from the fleet was able to sail directly through the sally port of the fort and pick up Tilghman for the surrender ceremony on Cincinnati, demonstrating the extent of flooding. Twelve officers and 82 men surrendered; other casualties are estimated to be 15 men killed and 20 wounded. The evacuating force left all of its artillery and equipment behind. Tilghman was imprisoned, but exchanged on August 15.[17]

Tilghman wrote bitterly in his report that Fort Henry was in a "wretched military position. ... The history of military engineering records no parallel to this case." Grant sent a brief dispatch to Halleck: "Fort Henry is ours. ... I shall take and destroy Fort Donelson on the 8th and return to Fort Henry." Halleck wired to Washington: "Fort Henry is ours. The flag is reestablished on the soil of Tennessee. It will never be removed."[18]

If Grant had been as cautious as other generals in the Union Army and had delayed his departure by two days, the battle would have never occurred, since by February 8, Fort Henry was completely underwater. The North treated Fort Henry as a glorious victory. On February 7, the gunboats Cincinnati, St. Louis, and Essex returned to Cairo with whistles blowing, flying Confederate flags upside down. The Chicago Tribune wrote that the battle was "one of the most complete and signal victories in the annals of the world's warfare."[19]

Fort Henry's fall opened the Tennessee River to Union gunboats and shipping past the Alabama border. This was quickly demonstrated. Immediately after the surrender, Foote sent Lieutenant Phelps with the three timberclads, the Tyler, Conestoga, and Lexington, on a mission up river to destroy installations and supplies of military value. (The ironclads of the flotilla had sustained damage in the bombardment and were slower and less maneuverable for the mission at hand, which would include pursuit of Confederate ships.) The raid reached as far as Muscle Shoals, just past Florence, Alabama, the limit of navigability. The Union ships and their raiding parties destroyed numerous supplies and the important bridge of the Memphis & Ohio Railroad, 25 miles (40 km) upriver. They also captured a variety of Southern ships, including the Sallie Wood, the Muscle, and an ironclad under construction, the Eastport. The Union ships returned safely to Fort Henry on February 12. However, Phelps made a major blunder during his otherwise successful raid. The citizens of the town of Florence asked him to spare their town and its railroad bridge, of the Memphis and Charleston Railroad. Phelps told them that he would, seeing no military importance to the bridge. Yet the loss of the bridge would have essentially split the Confederate theater in half. It was this bridge that Johnston's army would ride across on their journey to Corinth, Mississippi, in preparation for the Battle of Shiloh.[20]

After the fall of Fort Donelson to Grant's army on February 16, the two major water transportation routes in the Confederate west became Union highways for movement of troops and material. And as Grant suspected, this action flanked the Confederate forces at Columbus, causing them to withdraw from that city and Western Kentucky soon thereafter.[21]

Preservation

Although closely associated with Fort Donelson, the site of Fort Henry is not managed by the U.S. National Park Service as part of the Fort Donelson National Battlefield. It is currently memorialized as part of the Land Between the Lakes National Recreation Area. When the Tennessee River was dammed in the 1930s, creating Kentucky Lake, the remains of Fort Henry were submerged permanently. A small navigation beacon far from the Kentucky shoreline marks the location of the northwest corner of the former fortification. Fort Heiman was on privately owned land until October 2006, when the Calloway County, Kentucky, executive office transferred 150 acres (0.61 km2) associated with Fort Heiman to the National Park Service, for management as part of the Fort Donelson National Battlefield. Some of the entrenchments are still visible.[22]

Notes

- ^ a b c Estimates of Grant's troop strength vary. Cooling, pp. 11–12: 15,000. Gott, pp. 76–78: 15,000. Eicher, p. 169: 12,000; McPherson, p. 396: 15,000. Woodworth, p. 72: 17,000. Nevin, p. 61: 17,000. For the Confederate strength: Eicher, p. 171; Gott, pp. 54, 73; Cooling, p. 12.

- ^ a b NPS

- ^ Woodworth, p. 10.

- ^ Nevin, p. 46; Eicher, pp. 111–13; Gott, pp. 37–39; Cooling, p. 4.

- ^ Esposito, text to map 25; Nevin, p. 54.

- ^ Cooling, pp. 9–11; Eicher, p. 148; Gott, pp. 45, 46, 68, 69, 75; Esposito, map 25; Simon, p. 104.

- ^ Gott, p. 73; Cooling, p. 4.

- ^ Map of the Tennessee River for the use of the Mississippi Squadron under command of Acting Rear Admiral S. P. Lee, U.S.N., from reconnaissance by a party of the United States Coast Survey. 1864-'65., Sheet no. 5: 57 to 70 miles above Paducah.

- ^ Nevin, pp. 56–57; Gott, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Gott, pp. 17–18; Cooling, p. 5; Nevin, p. 57.

- ^ Eicher, p. 171; Gott, pp. 54, 73; Cooling, p. 12.

- ^ Nevin, pp. 62, 67; Cooling, pp. 5, 13; Gott, pp. 61, 62, 89.

- ^ Gott, pp. 62, 82.

- ^ Woodworth, pp. 73–74; Eicher, p. 171; Gott, p. 80.

- ^ Gott, pp. 88–89; Cooling, p. 13.

- ^ Nevin, pp. 63–65; Gott, pp. 92–95; Cooling, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Gott, pp. 97–98; McPherson, p. 397; Cooling, p. 15; Eicher, p. 172. Tilghman was imprisoned at Fort Warren in Boston and was exchanged for Union Brig. Gen. John F. Reynolds, captured at the Battle of Gaines' Mill; see biography.

- ^ Gott, p. 105.

- ^ Gott, pp. 105, 117.

- ^ Gott, pp. 107–14; McPherson, p. 397; Cooling, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Nevin, p. 101.

- ^ NPS FAQ on Forts Henry and Donelson; Clarksville, Tennessee Leaf-Chronicle article on Fort Heiman property transfer, published October 31, 2006.

References

- Cooling, Benjamin Franklin. The Campaign for Fort Donelson. National Park Service Civil War series. Fort Washington, PA: U.S. National Park Service and Eastern National, 1999. ISBN 1-888213-50-7.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Esposito, Vincent J. West Point Atlas of American Wars. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1959. OCLC 5890637. The collection of maps (without explanatory text) is available online at the West Point website.

- Gott, Kendall D. Where the South Lost the War: An Analysis of the Fort Henry—Fort Donelson Campaign, February 1862. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2003. ISBN 0-8117-0049-6.

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. Oxford History of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-19-503863-0.

- Nevin, David, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. The Road to Shiloh: Early Battles in the West. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1983. ISBN 0-8094-4716-9.

- Simon, John Y., ed. Papers of Ulysses S. Grant: January 8 - March 31, 1862. Vol. 4. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1972. ISBN 0-8093-0507-0.

- Woodworth, Steven E. Nothing but Victory: The Army of the Tennessee, 1861–1865. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. ISBN 0-375-41218-2.

- National Park Service battle description

Further reading

- Grant, Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant. 2 vols. Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885–86. ISBN 0-914427-67-9.

- Simpson, Brooks D. Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph over Adversity, 1822–1865. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2000. ISBN 0-395-65994-9.

External links

- Battles of the Federal Penetration up the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers of the American Civil War

- Battles of the Western Theater of the American Civil War

- Union victories of the American Civil War

- Naval battles of the American Civil War

- Tennessee in the American Civil War

- Forts in Tennessee

- Stewart County, Tennessee

- Henry County, Tennessee

- Calloway County, Kentucky

- Conflicts in 1862

- 1862 in Tennessee