Baxter Springs, Kansas

Baxter Springs | |

|---|---|

Downtown Baxter Springs (2008) | |

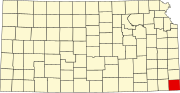

Location within Cherokee County and Kansas | |

| |

| Country | United States |

| State | Kansas |

| County | Cherokee |

| Incorporated | 1868 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–Council |

| • Mayor | Randy Trease[1] |

| Area | |

• Total | 3.19 sq mi (8.26 km2) |

| • Land | 3.11 sq mi (8.05 km2) |

| • Water | 0.08 sq mi (0.21 km2) |

| Elevation | 843 ft (257 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 4,238 |

• Estimate (2012[4]) | 4,162 |

| • Density | 1,362.7/sq mi (526.1/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 66713 |

| Area code | 620 |

| FIPS code | 20-04625 |

| GNIS feature ID | 1669487[5] |

| Website | BaxterSprings.us |

Baxter Springs is a city in Cherokee County, Kansas located along the Spring River. As of the 2010 census, the city population was 4,238.[6] It is the most populous city of Cherokee County.

From an early trading post, the city grew dramatically with the expansion of cattle ranching in the West and was the first "cow town" in Kansas following the Civil War. its population grew dramatically into the early 1870s in association with the cattle drives. After railroads were constructed into Texas, cattle drives no longer were made to Baxter Springs and other points along the trail, and the towns declined.

The city later had some economic success in the early twentieth century associated with lead mining in the area. The city protected its land, and owners and operators chose Baxter Springs for their residences and business offices. In 1926 the city's downtown main street was designated as part of the transcontinental U.S. Route 66 from Chicago to Los Angeles. By the 1940s, the high-quality lead had mostly been mined, and the industry declined. Some towns nearby disappeared altogether. Environmental restoration to correct damage left by mining has been underway for some time.

History

For thousands of years, indigenous peoples had lived along the waterways throughout the west. The Osage migrated west from the Ohio River area of Kentucky, driven out by the Iroquois. They settled in Kansas by the mid-17th century, adopting plains traditions, where they competed with other tribes. By 1750 they dominated much of the region of Kansas, Missouri and Oklahoma.

One of the largest Osage bands was led by Chief Black Dog (Manka - Chonka); his men completed the Black Dog Trail by 1803.[7][8] It started from their winter territory east of Baxter Springs and extended southwest to their summer hunting grounds at the Great Salt Plains in present-day Alfalfa County, Oklahoma.[8][9][10] The Osage stopped at the springs for healing on their way to summer hunting grounds. They made the trail by clearing it of brush and large rocks, and constructing earthen ramps to the fords. Wide enough for eight horsemen to ride abreast, the trail was the first improved road in Kansas and Oklahoma.[11]

Nineteenth-century settlers eventually named the city and nearby springs after its first European-American settler, A. Baxter, who claimed land about 1850 and built a frontier tavern or inn.[12] During the American Civil War, the United States government built several rudimentary military posts at present-day Baxter Springs, fortifying what had been a trading post: Fort Baxter, Camp Ben Butler and Camp Hunter.

In October 1863, the Confederate Quantrill's raiders attacked Fort Baxter, whose defense that day included a majority of infantry of United States Colored Troops.[12] The USCT held the fort, and Quantrill's men attacked a detachment of Union troops out on the prairie, in the Battle of Baxter Springs.[12] The Confederates outnumbered the Union forces outside the fort and killed nearly all of them, a total of 103 men.[13] After temporarily reinforcing the fort, the United States abandoned the Baxter Springs area later that year. It moved its troops to the better fortified Fort Scott, Kansas. Before leaving, US forces tore down and destroyed Fort Baxter to make it unusable for hostiles.[14]

By 1867, entrepreneurs in town had constructed a cable ferry across the Spring River, which was operated into the 1880s. At that time, it was replaced by the first bridge built across the river.

Around 1868 there was a great demand for beef in the North. Texas cattlemen and stock raisers drove large herds of cattle from the southern plains, and used Baxter Springs as a way point to the northern markets linking to railroads to the East. This led to the dramatic growth of Baxter Springs by the early 1870s as the first cow town in Kansas. By 1875, its population was estimated at 5,000.[12]

The town organized the Stockyards and Drovers Association to buy and sell cattle. They constructed corrals for up to 20,000 head of cattle, supplied with ample grazing lands and fresh water. Texas cattle trade stimulated the growth of related businesses, and Baxter Springs grew rapidly. At the same time that some settlers were building schools and churches, the town was the rowdy gathering place of cowboys, with associated saloons, livery stables, brothels and hotels to support their seasonal business.[15]

After railroads were constructed into Texas later in the century, cattlemen no longer needed Baxter Springs as a way station to the northern markets. The first railroad to enter Texas from the north, completed in 1872, was the Missouri–Kansas–Texas Railroad[16] As ranchers started shipping their beef directly from Texas, business in Baxter Springs and other cow towns fell off sharply.[15]

The discovery of lead in large veins in the tri-state area revived the area towns in the early twentieth century from the economic doldrums after the decline of the cattle drives. Lead had been found in small quantities and of poor quality in the early days of Baxter Springs along Spring Creek. It was suspected that higher grade ore could be found, but only at deeper depths. The Baxter Springs City Council by Ordinance 42 enacted provisions which greatly limited any mining within city limits. Their actions protected the land in the city; nearby towns have suffered from mining-related environmental degradation.[17]

Baxter Springs greatly benefited from the economic effects of regional mining activity. It was the residential choice of many of the mine owners and operators, who built ambitious houses to reflect their success. In addition, many mining executives built their business offices in Baxter Springs in the early 1900s. By the 1940s, however, much of the high-quality ore had been mined, and the industry declined in the region. Some towns became defunct, and "Hockerville, Lincolnville, Douthit, Zincville and others disappeared." The mining practices of the time caused considerable environmental degradation. Federal and state restoration efforts have helped to improve the land since the late twentieth century.[17]

A notable mine southwest of town was owned by the Estes family, a pioneering black family in the area who arrived after the Civil War, as did most incoming residents of the nineteenth century. The Estes mine was not the largest; however, it employed about 25 black workers in an industry marked by racial discrimination at the time.[17]

In 1926, the downtown main street became part of the historic Route 66 transcontinental highway connecting Chicago and Los Angeles. The designated highway was informally known as America's "Main Street" and had a prominent place in popular culture.[15] The town has reserved the land of Riverside Park along the Spring River for community access to its green banks.

2014 tornado

A tornado started near Quapaw, Oklahoma and moved through Baxter Springs on April 27, 2014.

Geography

Baxter Springs is located at 37°1′23″N 94°44′5″W / 37.02306°N 94.73472°W (37.023062, -94.734762).[18] The city is sited on the western bank of the Spring River at the edge of the Ozarks, in the Spring River basin. U.S. Route 69 Alternate and U.S. Route 166 have a junction at the city, and U.S. Route 400 bypasses it to the northeast. The center of town is less than two miles (3 km) from the Kansas-Oklahoma state border, though the incorporated area of the city extends to the border. It is also about 13 miles (21 km) west-southwest of Joplin, Missouri.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 3.19 square miles (8.26 km2), of which, 3.11 square miles (8.05 km2) is land and 0.08 square miles (0.21 km2) is water.[2]

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 1,284 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,177 | −8.3% | |

| 1890 | 1,248 | 6.0% | |

| 1900 | 1,641 | 31.5% | |

| 1910 | 1,598 | −2.6% | |

| 1920 | 3,608 | 125.8% | |

| 1930 | 4,541 | 25.9% | |

| 1940 | 4,921 | 8.4% | |

| 1950 | 4,647 | −5.6% | |

| 1960 | 4,498 | −3.2% | |

| 1970 | 4,489 | −0.2% | |

| 1980 | 4,773 | 6.3% | |

| 1990 | 4,351 | −8.8% | |

| 2000 | 4,602 | 5.8% | |

| 2010 | 4,238 | −7.9% | |

| 2014 (est.) | 4,073 | [19] | −3.9% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[20] 2012 Estimate[21] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[3] of 2010, there were 4,238 people, 1,754 households, and 1,151 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,362.7 inhabitants per square mile (526.1/km2). There were 2,053 housing units at an average density of 660.1 per square mile (254.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 85.2% White, 0.8% African American, 6.2% Native American, 0.4% Asian, 1.4% Pacific Islander, 0.4% from other races, and 5.7% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.7% of the population.

There were 1,754 households of which 33.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 47.9% were married couples living together, 12.7% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.0% had a male householder with no wife present, and 34.4% were non-families. 30.6% of all households were made up of individuals and 14.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.41 and the average family size was 2.99.

The median age in the city was 38 years. 26.1% of residents were under the age of 18; 8% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 25.1% were from 25 to 44; 25% were from 45 to 64; and 15.9% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.6% male and 51.4% female.

2000 census

As of the 2000 census, there were 4,602 people, 1,860 households, and 1,246 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,469.1 people per square mile (567.7/km²). There were 2,106 housing units at an average density of 672.3 per square mile (259.8/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 88.03% White, 0.98% Black or African American, 5.04% Native American, 0.20% Asian, 0.17% Pacific Islander, 0.48% from other races, and 5.11% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.30% of the population.

There were 1,860 households out of which 32.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 52.6% were married couples living together, 10.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 33.0% were non-families. 29.7% of all households were made up of individuals and 16.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.44 and the average family size was 3.02.

In the city the population was spread out with 26.5% under the age of 18, 9.2% from 18 to 24, 26.7% from 25 to 44, 20.8% from 45 to 64, and 16.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females there were 89.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 85.4 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $28,876, and the median income for a family was $33,933. Males had a median income of $27,005 versus $19,038 for females. The per capita income for the city was $13,789. About 9.3% of families and 10.2% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.5% of those under age 18 and 12.4% of those age 65 or over.

Popular Culture

Baxter Springs is mentioned in the song "Choctaw Bingo" by musician James McMurtry. Baxter Springs is also the setting for two of Canadian playwright, Norm Foster's plays; "Outlaw" and "Jenny's House of Joy".

Notable people

- Waylande Gregory (1905–1971), artist

- Hale Irwin, (born 1945), PGA golfer

- Charles Fox Parham (1873-1929), Penecostal leader

- Joe Don Rooney, (born 1975), lead guitarist for country pop trio Rascal Flatts

- H. Lee Scott, Jr., (born 1949), former President and CEO of Wal-Mart.

- Byron Stewart (born 1956), actor (The White Shadow, St. Elsewhere)

Gallery

- Historic Images of Baxter Springs, Special Photo Collections at Wichita State University Library

-

Route 66 Soda Fountain, 2008

-

Route 66 Welcome Center, 2010

-

Johnston Public Library, 2010

References

- ^ City Offices, Baxter Springs, 2007. Accessed 2008-10-20.

- ^ a b "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ^ a b "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ^ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2013-05-29.

- ^ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "2010 City Population and Housing Occupancy Status". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved June 14, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Black Dog Trail Marker". Retrieved 2012-01-14.

- ^ a b Burl E. Self, "Black Dog", Oklahoma Encyclopedia of History and Culture, accessed 5 Nov 2009

- ^ "Full text of "Wah Kon Tah The Osage And White Man S Road"". Retrieved 2012-01-14.

- ^ "DEXTER, "In The Flint Hills" KANSAS: BLACK DOG TRAIL.Photo of Chief Blackdog". Retrieved 2012-01-14.

- ^ Louis F. Burns, "Osage", Oklahoma Encyclopedia of History and Culture, accessed 5 Nov 2009

- ^ a b c d "Chapter XIII: The History of Baxter Springs", History of Cherokee County, Kansas and representative citizens, Ed. and comp. by Nathaniel Thompson Allison, 1904

- ^ http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/10/07/massacre-at-baxter-springs/?nl=opinion&emc=edit_ty_20131008&_r=0

- ^ Hugh L. Thompson, "Baxter Springs as a Military Post—1862–1863," Kansas in the Civil War Battles and Campaigns, Vol. 3, pp. 32-4 (from the Kansas State Historical Society).

- ^ a b c "History", City of Baxter Springs website, accessed 5 Nov 2009

- ^ Donovan L. Hofsommer. "Handbook of Texas Online – Missouri-Kansas-Texas railroad". Tshaonline.org. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- ^ a b c Tri-State Mining History, Baxter Springs Museum

- ^ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014". Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". Retrieved February 15, 2014.

Further reading

- County

- History of Cherokee County, Kansas; Nathanial Allison; Biographical Publishing; 646 pages; 1904. (Download 31MB PDF eBook)

- Kansas

- History of the State of Kansas; William G. Cutler; A.T. Andreas Publisher; 1883. (Online HTML eBook)

- Kansas : A Cyclopedia of State History, Embracing Events, Institutions, Industries, Counties, Cities, Towns, Prominent Persons, Etc.; 3 Volumes; Frank W. Blackmar; Standard Publishing Co; 944 / 955 / 824 pages; 1912. (Volume1 - Download 54MB PDF eBook),(Volume2 - Download 53MB PDF eBook), (Volume3 - Download 33MB PDF eBook)

External links

- City

- City of Baxter Springs

- Baxter Springs - Directory of Public Officials

- Baxter Springs Heritage Center and Museum

- Schools

- USD 508, local school district

- Maps

- Baxter Springs City Map, KDOT