Blood smear

| Blood film | |

|---|---|

Blood films, Giemsa stained | |

| ICD-9-CM | 90.5 |

| MedlinePlus | 003665 |

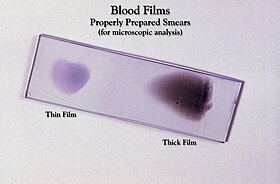

A blood film — or peripheral blood smear — is a thin layer of blood smeared on a glass microscope slide and then stained in such a way as to allow the various blood cells to be examined microscopically. Blood films are examined in the investigation of hematological (blood) disorders and are routinely employed to look for blood parasites, such as those of malaria and filariasis.

Preparation

Blood films are made by placing a drop of blood on one end of a slide, and using a spreader slide to disperse the blood over the slide's length. The aim is to get a region, called a monolayer, where the cells are spaced far enough apart to be counted and differentiated. The monolayer is found in the "feathered edge" created by the spreader slide as it draws the blood forward.

The slide is left to air dry, after which the blood is fixed to the slide by immersing it briefly in methanol. The fixative is essential for good staining and presentation of cellular detail. After fixation, the slide is stained to distinguish the cells from each other.

Routine analysis of blood in medical laboratories is usually performed on blood films stained with Romanowsky, Wright's, or Giemsa stain. Wright-Giemsa combination stain is also a popular choice. These stains allow for the detection of white blood cell, red blood cell, and platelet abnormalities. Hematopathologists often use other specialized stains to aid in the differential diagnosis of blood disorders.

After staining, the monolayer is viewed under a microscope using magnification up to 1000x. Individual cells are examined and their morphology is characterized and recorded.

Disorders

Characteristic red blood cell abnormalities are anemia, sickle cell anemia and spherocytosis. Sometimes the microscopic investigation of the red cells can be essential to the diagnosis of life-threatening disease (e.g. TTP).

White blood cells are classified according to their propensity to stain with particular substances, the shape of the nuclei and the granular inclusions.

- Neutrophil granulocytes usually make up close to 80% of the white count. They have multilobate nuclei and lightly staining granules. They assist in destruction of foreign particles by the immune system by phagocytosis and intracellular killing.

- Eosinophil granulocytes have granules that stain with eosin and play a role in allergy and parasitic disease. Eos have a multilobate nucleus.

- Basophil granulocytes are only seen occasionally. They are polymorphonucleated and their granules stain dark with alkaline stains, such as haematoxylin. They are further characterised by the fact that the granules seem to overlie the nucleus. Basophils are similar if not identical in cell lineage to mast cells, although no conclusive evidence to this end has been shown. Mast cells are "tissue basophils" and mediate certain immune reactions to allergens.

- Lymphocytes have very little cytoplasm and a large nucleus (high NC ratio) and are responsible for antigen-specific immune functions, either by antibodies (B cell) or by direct cytotoxicity (T cell). The distinction between B and T cells cannot be made by light microscopy.

- Plasma cells are mature B lymphocytes that engage in the production of one specific antibody. They are characterised by light basophilic staining and a very eccentric nucleus.

- Other cells are white cell precursors. When these are very abundant it can be a feature of infection or leukemia, although the most common types of leukemia (CML and CLL) are characterised by mature cells, and have more of an abnormal appearance on light microscopy (additional tests can aid the diagnosis).

Malaria

The preferred and most reliable diagnosis of malaria is microscopic examination of blood films, because each of the four major parasite species has distinguishing characteristics. Two sorts of blood film are traditionally used.

- Thin films are similar to usual blood films and allow species identification, because the parasite's appearance is best preserved in this preparation.

- Thick films allow the microscopist to screen a larger volume of blood and are about eleven times more sensitive than the thin film, so picking up low levels of infection is easier on the thick film, but the appearance of the parasite is much more distorted and therefore distinguishing between the different species can be much more difficult.[1]

From the thick film, an experienced microscopist can detect all parasites they encounter. Microscopic diagnosis can be difficult because the early trophozoites ("ring form") of all four species look identical and it is never possible to diagnose species on the basis of a single ring form; species identification is always based on several trophozoites. Please refer to the chapters on each parasite for their microscopic appearances: P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae.

The biggest pitfall in most laboratories in developed countries is leaving too great a delay between taking the blood sample and making the blood films. As blood cools to room temperature, male gametocytes will divide and release microgametes: these are long sinuous filamentous structures that can be mistaken for organisms such as Borrelia. If the blood is kept at warmer temperatures, schizonts will rupture and merozoites invading erythrocytes will mistakenly give the appearance of the accolé form of P. falciparum. If P. vivax or P. ovale is left for several hours in EDTA, the buildup of acid in the sample will cause the parasitised erythrocytes to shrink and the parasite will roll up, simulating the appearance of P. malariae. This problem is made worse if anticoagulants such as heparin or citrate are used. The anticoagulant that causes the least problems is EDTA. Romanowsky stain or a variant stain is usually used. Some laboratories mistakenly use the same staining pH as they do for routine haematology blood films (pH 6.8): malaria blood films must be stained at pH 7.2, or Schüffner's dots and James's dots will not be seen.

References

- ^ Warhurst DC, Williams JE (1996). "Laboratory diagnosis of malaria". J Clin Pathol. 49 (7): 533–38. doi:10.1136/jcp.49.7.533. PMC 500564. PMID 8813948.