Bombus lapidarius

| Red-tailed bumblebee | |

|---|---|

| |

| Worker | |

| |

| Male | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Subfamily: | |

| Tribe: | |

| Genus: | |

| Subgenus: | |

| Species: | B. lapidarius

|

| Binomial name | |

| Bombus lapidarius | |

Bombus lapidarius is a species of bumblebee in the subgenus Melanobombus. Commonly known as the red-tailed bumblebee, B. lapidarius can be found throughout much of Central Europe. Known for its distinctive black and red body, this social bee is important in pollination.[2]

Taxonomy and Phylogeny

The red-tailed bumblebee is a part of the Hymenoptera order, Apidae family, and the Bombus genus, which includes many species including Bombus genalis, Bombus angustus, and Bombus nobilis.

Description and Identification

The red-tailed bumblebee is typically distinguished by its black body with red markings around the abdomen. Worker females and the queen look similar, except the queen is much larger than the worker females. Males typically have both the red and black as well as a yellow band around the abdomen and yellow markings on the face. These bees do not typically form extensive or complex colonies.[3] These nests usually only contain a few hundred bees, at most.[4] B. lapidarius nests have been found in many different habitats, but the bees typically prefer open terrain as opposed to more heavily forested landscapes.[5] Further, B. lapidarius tend to have a medium sized proboscis, which is significant in that it allows the species to be a good pollinator.[6] Their nests are built in cairns or walls, which explains the literal meanings of their common names in various Germanic languages: "Stone bumblebee" (cf. German: Steinhummel, Swedish: Stenhumla). They are also found in the straw of stables or in abandoned birds' nests. An average colony consists of about 100 to 200 worker bees. Red-tailed bumblebees prefer the nectar of various species of clover and deadnettle.

Distribution and Habitat

Bombus lapidarius is often found throughout Europe, including England as well as parts of Germany, Sweden, Ireland and Finland.[7] This species typically has a fairly wide distribution.[3] As described in the foraging patterns section, they can fly over 1500 meters to better forage for food. They typically are found in temperate regions. Further, colonies are often found in open terrain.[3]

Colony Cycle

Red-tailed bumblebees typically appear in the summer months of June, July, and August.[8] Colonies are initiated via the queen, where workers and males follow roles to keep the colony thriving. Though there is a hierarchy between the queen and the rest of the colony, there does not appear to be a hierarchy between the workers themselves.[9]

Behavior

Courtship Behavior

Red-tailed bumblebee males utilize sexual pheromones to attract females. Males will fly around and mark spots with the pheromone compounds (Z)-9-hexadecenol and hexadecanal via their labial gland. These secretions are highly species specific, thus likely greatly reduce inter-species mating. B. lapidarius typically fly and secrete above the treetops, which are more affected by the effects of the wind and the sun. Therefore, this species typically has to secrete more pheromone than other species to be effective.[10] Further, these compounds were found in trace amounts in the air around the areas that individuals had scent marked.[11] Different populations differing in location (specifically Southern Italy, the Balkans, and Centre-Eastern Europe) have experienced genetic differentiation in pheromone composition.[2]

Queen Pheromones

Queen red-tailed bumblebees also appear to secrete pheromones. Functionally, these pheromones appear to inhibit ovarian development in worker bees. Although it is still unclear what the true function of the queen’s pheromones are, the pheromones that are secreted are chemically quite different than those of the workers.[12]

Foraging Patterns

B. lapidarius has been found to be one of the more dominant species when foraging and have been found to travel as far as 1750 meters to forage for resources such as Phacelia tenuifolia.[8] Interestingly, however, it appears that individual bumblebees vary greatly in distance traveled in foraging efforts. Although there were differences in foraging for each individual bee as well as for each species, studies suggest that B. lapidarius are willing to travel very large distances. In fact, these bees appear to be able to travel 11.5 kilometers away from their nests.[8]

Males and Workers

Males have been found to have traveled a much greater range than workers.[13] This behavior may help lead to greater genetic variation, as populations appear to be diverse and avoid inbreeding. Workers, in comparison, tend to stay closer to the nest. Workers are often invested in cell building within the nest.[9] Furthermore, B. lapidarius workers do not appear to have a hierarchy between them, which differs from many other species.

Diet

Red-tailed bumblebees typically will eat pollen and nectar.[10] Interestingly, workers will sometimes attempt to eat eggs the queen has laid.[9] The queen makes a valiant effort to prevent this from happening, but the workers are successful in this attempt fairly frequently. Though the queen would not attempt to hurt or injure workers engaging in this activity, she would threaten them with her mandible or hit the workers with her head.[9] Though this is not well understood, it provides an interesting question for further study.

Interaction With Other Species

Parasites

Bombus lapidarius often experiences parasites, including different species from the Psithyrus genus.[14] All Psithyrus species lack a worker caste - instead the female queen cuckoo bee will invade the nest of a host species and lay her eggs there. These cuckoo bees utilize different mechanisms via chemical recognition systems, including mimicry and repulsion, to invade B. lapidarius nests. By mimicking both physical traits as well as chemical secretions, cuckoos have evolved to mimic B. lapidarius species in particular. Typically, species avoid cuckoo parasitism by emitting complex hydrocarbons.[14] These hydrocarbons are how species such as the red-tailed bumblebee recognize each other. However, cuckoos are able to copy these hydrocarbons in order to introduce themselves into a host colony. However, if cuckoos do not match the B. lapidarius traits in these ways, parasitism can still be achieved via repulsion. Cuckoos can produce a worker repellent, thus again allowing the parasitic species to survive within the group. Hosts will either raise these cuckoos as their own, or cuckoos will invade and become a part of the B. lapidarius colony. Occasionally, Psithyrus queens will even eat B. lapidarius eggs if her own brood is becoming nutritionally deficient.[14]

Mutualism

Red-tailed bumblebees are very important for pollination for many different species of flower and crops.[15] Further, B. lapidarius was found to forage and pollinate at higher temperatures than other Bombus species.[16] This is important for understanding when and where pollination will best occur.

Human Importance

Stings

This species is a type of bumblebee, thus has the ability to sting.[2]

Agriculture

This bee is a very important part of pollination. For many species of plant, such as species of Viscaria, only bees and butterflies have proboscides long enough to pollinate effectively. [17] This importance is reinforced by studies which show B. lapidarius was more numerous and had a higher feeding density than other species studied[17]

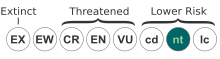

Conservation status

Red-tailed bumblebees rank among the most common and most recognized bumblebees of Central Europe, but rarer species have similar appearances, such as Bombus ruderarius.

This species is widespread across Ireland, though some evidence indicates the species is declining in agricultural grasslands.[18] It is considered Near Threatened in Ireland.[19]

References

- ^ ITIS Report

- ^ a b c Lecocq, Thomas (December 2013). "Scent of a break-up: phylogeny and reproductive trait differences in the red-tailed bumblebee ("Bombus lapidarius")". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 13 (263).

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c Svensson, Birgitta (February 2000). "Habitat preferences of nest-seeking bumble bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in an agricultural landscape". 77 (3): 247–255.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) Cite error: The named reference "habitat" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Schultze-Motel, P (January 1991). "Heat loss and thermoregulation in a nest of a bumblebee Bombus Lapidarius (Hymenoptera, Apidae)". Thermochimica Acta. 193: 57–66.

- ^ Schultze-Motel, P. (January 1991). "Heat loss and thermoregulation in a nest of the bumblebee Bombus lapidarius (Hymenoptera, Apidae)". Thermochimica Acta. 193: 57–66.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Jennerson, Ola (November 1993). "Insect flower visitation frequency and seed production in relation to patch size of Viscara vulgaris (Caryophyllaceae)". OIKOS. 68 (2): 283–292.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Martin, Stephen (May 2010). "Host specific social parasites (Psithyrus) indicate chemical recognition system in bumblebees". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 36 (8): 855–863.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c Walther-Hellwig, K. (2000). "Foraging habitats and foraging distances of bumblebees, Bombus spp. (Hym., Apidae), in an agricultural landscape". JAE. 124: 299–306.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c d Free, J.B. (1969). "The Egg-Eating Behaviour of Bombus lapidarius L.". Behavior. 35 (3): 313–317.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b Ayasse, M (January 2001). "Mating behavior and chemical communication in the order hymenoptera". Annual Review of Entomology. 46.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Bergman, Peter (May 1997). "Scent Marking, Scent Origin, and Species Specificity in Male Premating Behavior of Two Scandinavian Bumblebees". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 23 (5): 1235–1251.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Cahlikova, Lucie (February 2004). "Exocrine Gland Secretions of Virgin Queens of Five Bumblebee Species (Hymenoptera: Apidae, Bombini)". Naturforsch. 59.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Wolf, Stephan (January 2012). "Spatial and temporal dynamics of the male effective population size in bumblebees (Hymenoptera: Apidae)". Population Ecology. 54 (1): 115.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ a b c Martin, Stephen (August 2010). "Host Specific Social Parasites (Psithyrus) Indicate Chemical Recognition System in Bumblebees". Journal of Chemical Ecology. 36 (8): 855.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ Knight, M (April 2005). "An interspecific comparison of foraging range and nest density of four bumblebee (Bombus) species". Molecular Ecology. 14 (6): 1811.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ Corbet, Sarah (1993). "Temperature and the pollinating activity of social bees". Ecological Entomology. 18: 17.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ a b Jennersten, Ola (November 1993). "Insect Flower Visitation Frequency and Seed Production in Relation to Patch Size of Viscaria vulgaris (Caryophyllaceae)". OIKOS. 68 (2): 283.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^ http://www.npws.ie/en/media/NPWS/Publications/Redlists/Media,4860,en.pdf

- ^ Fitzpatrick, U., T.E. Murray, A. Byrne, R.J. Paxton & M.J.F. Brown (2006) Regional red list of Irish Bees. Report to National Parks and Wildlife Service (Ireland) and Environment and Heritage Service (N. Ireland).

- Leisering, Horst; Michael Lohmann (1998). Großer Naturführer in Farbe (Great coloured Guide to Nature) (in German). Compact Verlag, Munich. ISBN 3-8174-5229-2.