Broadway Tunnel (San Francisco)

Western portal, from inside the north tunnel, facing west | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Location | San Francisco, California |

| Coordinates | 37°47′49″N 122°24′54″W / 37.796812°N 122.414893°W |

| Route | Broadway |

| Operation | |

| Work begun | May 1, 1950 |

| Opened | December 21, 1952 |

| Owner | City of San Francisco |

| Operator | City of San Francisco |

| Traffic | Automotive and pedestrian |

| Technical | |

| Length | 1,616 ft (493 m) |

| No. of lanes | 4 |

| Operating speed | 40 mph (64 km/h) |

| Tunnel clearance | 13.5 ft (4.1 m) |

The Broadway Tunnel (officially the Robert C. Levy Tunnel) is a roadway tunnel in San Francisco, California. The tunnel opened in 1952, and serves as a high-capacity conduit for traffic between Chinatown and North Beach to the east and Russian Hill and Van Ness Avenue to the west. In a proposal of the city's 1948 Transportation Plan, the tunnel was to serve as a link between the Embarcadero Freeway and the Central Freeway.

History

Early plans

Abner Doble (grandfather of the namesake who would go on to build steam-powered cars) and his associates in the Folsom St. and Fort Point Railroad and Tunnel Co. were granted "the right to construct a tunnel through Russian Hill, on the line of Broadway, from Mason to Hyde or Larkin" by the California State Assembly on April 22, 1863.[1]: 414 [2][3]

Fifty years later, Bion J. Arnold submitted a report to the City of San Francisco in March 1913, calling for a tunnel on Broadway to supplement the Stockton Street Tunnel, which was already under construction.[1] The general route of a tunnel for Broadway was described in April 1913, extending from Mason to Larkin.[4] A landowner protested against the proposed tunnel, calling it "absolutely as unnecessary as a bridge to the moon."[5] Also in 1913, a railway tunnel was proposed for Broadway as part of an extension for the Municipal Railway to carry passengers to and from the Panama-Pacific Exposition.[6] Arnold's proposal called for a combined rail and road tunnel with a single arch for Broadway through Russian Hill, 2,338 feet (713 m) long and 60 feet (18 m) wide, carrying two tracks each 11 feet (3.4 m) wide; three lanes of traffic 24 feet (7.3 m) wide in total; and two sidewalks each 7 feet (2.1 m) wide..[1]: 220, 222–224

Plans were elaborated in brief by City Engineer M.M. O'Shaughnessy as one of ten potential tunnel projects in San Francisco at the October 1917 meeting for the San Francisco Association of the members of the American Society of Civil Engineers. O'Shaughnessy proposed a 2,300-foot (700 m) long bore, but the article reporting the meeting described it as merely "investigated and not likely to be soon built."[7]

Construction

In 1948, voters in the City of San Francisco passed a $5 million bond measure (equivalent to $51 million in 2023) to fund the construction of the Broadway Tunnel.[8] Site preparations, including the move of an apartment building from 1453 Mason to Vallejo Street,[9] were underway by October 1949, and the construction contract was anticipated to be bid in January 1950.[10] In February, Morrison-Knudsen was awarded the contract after submitting the low bid of $5,243,355[11] and construction began in May 1950.[12] The final cost was some $7,300,000.[13]

Completion was originally projected for May 1952, but unanticipated loose rock meant that shoring was required.[14] The tunnel opened to traffic on December 21, 1952.[13] Mayor Elmer Robinson cut a ceremonial ribbon to mark the occasion.[12]

Dedication and later years

The Broadway Tunnel was named in honor of Robert C. Levy (1921-1985) in January 1986. Mr. Levy was the City Engineer and Superintendent of Building Inspection for the City and County of San Francisco. A plaque outside the tunnel reads, "He devoted his life to high standards of professionalism in engineering and to the City which he loved."

Design

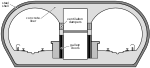

The east portal is just east of the Mason Street overpass. The west portal is just east of the Hyde Street overpass. Combined with these two overpasses, the tunnel provides for uninterrupted traffic flow along Broadway for a stretch of six blocks, between Powell on the east and Larkin on the west. There are two bores, each carrying two lanes of one-way traffic. The northern tunnel carries westbound traffic, and the southern tunnel carries eastbound traffic. Each tunnel is 1,616 feet (493 m) long.[13]

The vertical clearance throughout much of the tunnel is nearly 20 feet (6.1 m), but there is an overhanging concrete slab at the eastern end, which reduces vertical clearance to 13 ft 6 in (4.11 m).[15]

There are narrow sidewalks on the outboard side of each tunnel (e.g., the north side of the westbound tunnel). Bicyclists tend to use the sidewalk, but signal lights triggered by an inductive loop were installed in 2011 to alert motorists to the presence of bicycles in the tunnel.[16]

Public art and architecture

A stylized dragon relief sculpture by Patti Bowler, rendered in bronze, has been mounted above the eastern portal of the tunnel since 1969.[17][18] The building atop the eastern portal is the Chinatown Public Health Center (Chinese: 華埠公共衛生局), a public health clinic operated by the San Francisco Department of Public Health.[19] It was built in the 1970s and remodeled in 2010.[20]

In 2008, the artist Moose, sponsored by the company Green Works, executed a 140-foot (43 m) long mural by cleaning dirt from the side of the approach to the western portal of the tunnel using pressure washing and cardboard stencils, a technique known as reverse graffiti.[21]

In popular media

The Broadway Tunnel has been used as a filming location for several motion pictures, including:[22]

- Hells Angels on Wheels (1967)[23]

- Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978)[22]

- Magnum Force (1973)[22]

- The Princess Diaries (2001)[22]

- War (2007)[24]

- What Dreams May Come (1998)[25]

See also

References

- ^ a b c Arnold, Bion J. (March 1913). "10. Tunnels into Harbor View". Report on the Improvement and Development of the Transportation Facilities of San Francisco (Report). Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ "Appendix: Railroad Franchises". San Francisco Municipal Reports for the Fiscal Year 1879-80 Ending June 30, 1880 (Report). San Francisco Board of Supervisors. p. 914. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ California State Assembly. "An Act to provide for the construction of a Street Railroad and Tunnel through Russian Hill, in the City and County of San Francisco". Fourteenth Session of the Legislature. Statutes of California. State of California. Ch. 293 p. 392.

The right is hereby given to Abner Doble, I.T. Pennel, Joseph M. Wood, I.W. Cudworth, to them and their associates and assigns, to construct a tunnel in the City and County of San Francisco, through Russian Hill, on the line of Broadway street, from Mason street to Hyde or Larkin street, with the exclusive use of said tunnel, and the right to charge tolls upon animals and vehicles which may pass through the same. Said tunnel shall not be less than twenty feet in width, by sixteen feet in height, in the centre chord thereof; the entrances, shafts, slopes, and open cuts, shall be protected with suitable railings, walls, etc., to prevent accidents; [...]

- ^ "Tunnel Committee Makes Progress Report". Municipal Record. VI (17). San Francisco Board of Supervisors: 78. 24 April 1913. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "Protests Against Proposed Broadway Tunnel". Municipal Record. VI (10). San Francisco Board of Supervisors: 130. 6 March 1913. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ O'Shaughnessy, M. M. (5 April 1913). Report on Extension of Municipal Railways to Provide Transportation for the Panama-Pacific Exposition (Report). San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "City Engineer Describes City Tunnels". Municipal Record. X (50). San Francisco Board of Supervisors: 409–410. 13 December 1917. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ Wallace, Kevin (27 March 1949). "The City's Tunnels: When S.F. Can't Go Over, It Goes Under Its Hills". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- ^ Donovan, Diane C.; Montgomery, Steve (2015). San Francisco Relocated. Arcadia Publishing. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-4671-3371-5. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ "Broadway Tunnel Brings Sausalito Closer to S.F." Sausalito News. 27 October 1949. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "Low Bidder Named for Bay City Tunnel Job". San Bernardino Sun. AP. 3 February 1950. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ a b "Broadway Tunnel Opened To Traffic". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 22 December 1952. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ a b c "Broadway Tunnel Opens Sunday; Will Cut Travel Time from Sausalito to S.F." Sausalito News. 18 December 1952. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "S.F. Tunnel Job Faces New Delay". Sausalito News. 10 April 1952. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ Egelko, Bob (19 August 2006). "SAN FRANCISCO / Tunnel death suit rejected". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ Bialick, Aaron (3 June 2011). "SFMTA Installs Bike and Ped Lights on the Broadway Tunnel and Tenderloin". Streetsblog SF. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ Cindy (28 March 2012). "Chinatown – Broadway Tunnel". Art and Architecture SF. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "Dragon Relief, (sculpture)". Smithsonian American Art Museum. 1969. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "Chinatown Public Health Center". San Francisco Health Network. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "Chinatown Health Center". San Francisco Department of Public Works. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ Colom, Francisco. "Reverse Graffiti Project in San Francisco". More Than Green. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Film Locations in San Francisco" (PDF). City of San Francisco. 17 April 2018. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ Wethern, George; Colnett, Vincent (1978). A Wayward Angel: The Full Story of the Hells Angels. Richard Marek Publishers. ISBN 1-59228-385-3. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "Broadway Tunnel to close for film car chase Sunday". San Francisco Examiner. 14 October 2006. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ "What Dreams May Come". Film in America. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

External links

- A trip through Broadway Tunnel on YouTube

- De Leuw, Cather and Company (1948). A Report to the City Planning Commission on a Transportation Plan for San Francisco. City Planning Commission, San Francisco. OCLC 7431642.

- Rhodes, Michael (25 May 2010). "The Broadway Tunnel: One of SF's Meanest Streets for Biking and Walking". Streetsblog SF. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Broadway Tunnel East Mini Park". San Francisco Department of Recreation and Parks. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Broadway Tunnel West Mini Park". San Francisco Department of Recreation and Parks. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- San Francisco County Transportation Authority (July 2015). Chinatown Neighborhood Transportation Plan (PDF) (Report). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- DDB (25 June 2009). "Reverse graffiti". Ads of the World. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Best Tunnel: Broadway Tunnel". SF Weekly. 2003. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- "Broadway Tunnel". Bridgehunter. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- "San Francisco tunnel open to traffic". Engineering News-Record. Vol. 149. McGraw-Hill. 1952. p. 50.