Campaign of Grodno

| Campaign of Grodno | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Invasion of Poland, Great Northern War | |||||||

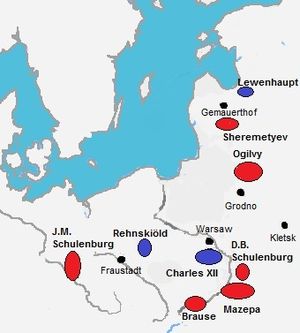

Strategical view, late 1705 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

51,000: 10,000 Polish and Lithuanian[2] |

117,500: 23,500 Saxon[1] 20,000 Cossack[1] 16,000 Polish and Lithuanian[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

6,900 or more in larger battles and sieges ..see casualties |

43,000 or more in larger battles and sieges ..see casualties | ||||||

The Campaign of Grodno was a plan developed by Johann Patkul and Otto Arnold von Paykull during the Swedish invasion of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a part of the Great Northern War. Its purpose was to crush Charles XII's army with overwhelming force in a combined offensive of Russian and Saxon troops. The campaign, executed by Peter I of Russia and Augustus II of Saxony, began in July 1705 and lasted almost a year. In divided areas the allies would jointly strike the Swedish troops occupied in Poland, in order to neutralize the influence the Swedes had in the Polish politics. However, the Swedish forces under Charles XII successfully outmaneuvered the allies, installed a Polish king in favor of their own and finally won two decisive victories at Grodno and Fraustadt in 1706. This resulted in the Treaty of Altranstädt (1706) in which Augustus renounced his claims to the Polish throne, broke off his alliance with Russia, and established peace between Sweden and Saxony.

The campaign led to Sweden gaining control over the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, until the Swedish defeat at Battle of Poltava and the Treaty of Thorn (1709) which restored the Russian-backed Augustus to the Polish throne and forced the remaining Swedes out of the Commonwealth.

Background

In 1700 Sweden was attacked by a coalition of Saxony, Russia, and Denmark–Norway. Saxony, under Augustus II, invaded Swedish oversea dominions in Livonia and quickly attacked the city of Riga. Meanwhile, Frederick IV of Denmark attacked the Swedish allied duchies of Holstein and Gottorp in order to secure his rear, before commencing with the planned invasion of Scania, which had been previously annexed by Sweden in the Treaty of Roskilde in 1658. A short time later, Russia under Peter I swept into Swedish Ingria and besieged the strategic city of Narva. Unprepared for these developments, the Swedes were forced into a war on three fronts.[3]

First year

Despite their significant military advantage the allied armies encountered immediate setbacks. Denmark–Norway was quickly knocked out of the war by a bold Swedish landing on Humlebæk resulting in the Peace of Travendal. After this development, the Swedish army under Charles XII was free to sail east across the Baltic sea to tackle the remaining opponents, Russia and Saxony.[4] In response to this threat, Augustus lifted the siege of Riga and marched back across the Düna river in order to observe the Swedish movements. Charles then decided to march against Peter I of Russia, who was besieging Narva, with the aim of saving the city. Shortly later the two armies met in the battle of Narva. This ended in a decisive Swedish victory which greatly crippled the Russian army, forcing them to abandon their campaign in Swedish territory and withdraw to Russia.[5]

Invasion of Poland

Having secured two quick and decisive victories over his opponents which greatly increased his reputation, Charles marched against the Saxon forces in early 1701. These were camped on the opposite bank of the Düna. The clash occurred in the battle of Düna, ending in another Swedish victory. However, the outcome was not as decisive as Charles had hoped for.[5] A large part of Augustus' army survived and marched into neutral Prussia. As a consequence, Charles was not able to capitalize on the previous Russian setback at Narva, but was forced to postpone the planned invasion. Instead he decided to chase the Saxon army into the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, where Augustus was also king. Thus far, technically, Poland-Lithuania had stayed neutral in the conflict since Augustus began the war with Sweden in his capacity as Elector of Saxony rather than as king of Poland. Charles' purpose was to remove Augustus from the Polish throne. The subsequent conflict became known as the Swedish invasion of Poland.[6][7]

In 1702, after having seized the Polish capital of Warsaw, Charles caught up and won a battle against Saxon and Polish armies at Kliszów.[8] Even though the Swedish victory was not decisive, factions within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth began supporting the Swedish cause, in opposition to Augustus. This triggered the Polish civil war of 1704-1706.[7] The reputation of Charles and his army grew and they soon took Kraków, the "second Polish capital".[9] Minor operations and skirmishes followed, as the Saxon and Polish–Lithuanian armies preferred to avoid facing the Swedes in direct battle.[10]

After engagements at Pultusk and Toruń in 1703[11] Augustus was finally forced to abdicate the Polish throne in 1704, in favor of a monarch installed by the Swedes, Stanisław I Leszczyński. Charles and Leszczyński were supported by the Warsaw Confederation of Polish nobles.[12] In opposition to these developments the Sandomierz Confederation was created by other nobles in support of Augustus. The latter could call on about 75% of the military capacity of the Polish army.[13] Some smaller engagements at Poznań, Lwów, Warsaw and Poniec followed in 1704 as a consequence of Augustus' attempts to retake the throne.[14]

The campaign

Up until early 1705, Peter's efforts were focused on Livonia and Ingria, and there were few direct confrontations against the Swedish main army in Poland. After the initial outcomes in the Polish theater however, Peter assembled his army closer to the Commonwealth in order to provide assistance to Augustus against Charles, and to put pressure on the local nobility in an attempt to restore Augustus to the Polish throne.[15] The Swedish army in turn, spent the first half of the year close to Rawicz in order to secure the coronation of Stanisław Leszczyński.[16]

Opposing forces

The Russian–Saxon–Polish allies assembled their armies in Lithuania for a joint offensive against the Swedes. Their troops consisted of four contingents; the main Russian army of 50,000 men under Georg Benedict Ogilvy near Polotsk, another 8,000 Russians and 10,000 Lithuanians loyal to Augustus close to Vilnius, about 6,000 Poles and 3,500 Saxons under Otto Arnold von Paykull at Brest-Litovsk[15] and 20,000 Cossacks under Ivan Mazepa in Volhynia. In Saxony close to 20,000 men were recruited for the main Saxon army under Johann Matthias von der Schulenburg. In all, the allied forces enjoyed a massive advantage as their forces counted almost 120,000 men against the 35,000 Swedes[1] and 10,000 Poles and Lithuanians[2] in Poland under Charles and the 6,000 men in Courland under Adam Ludwig Lewenhaupt.[1]

Plan of attack

In early March 1705 the Russian Field Marshal Boris Sheremetyev set up a meeting with the Saxon general Otto Arnold von Paykull in order to agree to a common course of action in the ensuing campaign. The basis for the strategy was a plan developed by Johann Patkul as early as 1703, which envisioned a joint strike which would neutralize the Swedish army. von Paykull, inspired by Patkul's blueprint, advocated it as a way to lure Charles and the main Swedish army out of Greater Poland eastward towards Brest-Litovsk. This was to be accomplished by having the combined forces of the main Russian army under Ogilvy and von Paykull's troops stationed at Brest, which would force Charles to meet them in battle. At the same time the main Saxon army would attack Charles from the rear by sweeping through Poland out of Saxony, ultimately catching the Swedish army exposed. The plan seemed rather daring to Patkul and he suggested that the allies should first crush Lewenhaupt's army, before Ogilvy's troops approached Charles. Otherwise Ogilvy's rear would be threatened.[17] A compromise was made between the two strategies and it was decided that Sheremetyev should engage Lewenhaupt at the same time as Ogilvy marched towards the strongly fortified city of Grodno. The belief was that there, behind fortifications, Oglivy would be able to withstand Charles long enough for the main Saxon army to arrive from Kraków. Meanwhile, von Paykull would attack with his combined Saxon–Polish force towards Warsaw in order to interrupt the coronation of Stanisław I.[18]

Campaign begins

The Saxon–Russian plans were put into action in early July as Sheremetyev began his march towards Lewenhaupt in Courland. The two armies met on July 26, at the battle of Gemauerthof where the Russians were defeated. Despite the outcome Lewenhaupt chose to withdraw back to Riga having suffered notable losses himself, leaving Courland open for Peter I to occupy with freshly arrived reinforcements. This worked in favor of the allies as the rear of Ogilvy's army which was marching towards Grodno was now secured accordingly.[18]

Only five days later, on July 31, Paykull reached the outskirts of Warsaw with his army and in a surprise attack attempted to interrupt the coronation of Stanisław. In the ensuing battle of Warsaw the much smaller Swedish force under Carl Nieroth guarding the city won a decisive victory. Paykull was captured along with secret documents which informed the Swedes of a possible attack on Warsaw by a larger Russian army under Peter.[19]

It now seems, as if the war will begin for real and have every Swede at once, by the great number of nations surrounding him, engrossed....

— Gentleman of the court, Gustaf Adlerfelt, 1705[20]

After having received this information while at Rawicz, Charles struck camp on August 8 and marched closer to Warsaw in order to fully protect the city until the coronation of Leszczyński was completed.[18] He left General Carl Gustaf Rehnskiöld with 10,000 men at Poznań to guard against the main Saxon army under Schulenburg which threatened to enter Poland.[21] On September 15, Peter I seized the town of Mitau in Courland.[22] However, the allied successes were limited as the coronation of Leszczyński as Stanisław I of Poland was completed on October 4.[23]

Later the same month, on October 25, the allies made a quick push to destroy the bridge going over the Vistula, from Warsaw to Praga, in order to slow down the Swedish troop movements. However, the attack was repulsed by a handful of men.[24] A month later, on November 28, Sweden and Poland made peace in the Treaty of Warsaw through the Warsaw Confederation which increased Sweden's position even further. Charles could now march, after having waited more than a year since Augustus was dethroned, against the Russian army under Ogilvy which had already by this time reached Grodno.[25]

Being somewhat delayed, Charles broke up his winter quarters at Blonie on January 9, 1706 and approached Grodno with the main Swedish army of 20,000 men[26] and the 10,000 Poles and Lithuanians.[2] A Russian army of 28,000 men was stationed there.[26][27] Bad weather prevented him from marching out earlier. Urgently seeking battle Charles seemed to walk straight into the trap the allies had set for him, according to their initial plan. In Saxony, Schulenburg still waited with his 20,000 men to cross the Polish border and engage Rehnskiöld. He planned to move with his army as soon as he got word of Charles crossing the Vistula river.[26] However, Charles commenced with a rapid winter march; this was typical for the Swedes, dating back to the time of Gustavus Adolphus, but quite unusual for continental armies.[28] This in turn surprised the allies as they believed Charles would not begin his march before spring.[26] Having received word of his approach however, they considered three alternatives; to meet Charles' army in the open field, fortify in Grodno, or retreat. While they disagreed among themselves about their course of action Charles' army appeared before the fortifications of Grodno on January 24, after a quick march, forcing the allies to stay in the city.[29] Prior to the Swedish arrival, Augustus who had thus far accompanied the Russian army, broke away with 5,000 cavalry.[30] He strove to increase his troops with another 3,000 men[31] before uniting forces with Sculenburg and the Saxon main army whose only obstacle in order to attack Charles' army in the rear, accordingly, were the 10,000 men under Rehnskiöld stationed at Poznań.[32][33]

Main confrontation

After having scouted the Russian fortifications at Grodno, Charles realized a frontal assault would be impossible. At the same time, the Russians would not let themselves be provoked out into the field. Charles instead decided to try and starve them out by crossing the Neman river in January 15, encircling the city from the east, forcing 15,000 Russian cavalry to withdraw.[34][35] In doing this he blocked the Russian communication lines, and also cut off their resources and supplies.[34] Smaller Swedish parties were sent towards Vilnius in order to prevent General Christian Felix Bauer from supplying the trapped Russians. One of these, commanded by Jan Kazimierz Sapieha and Józef Potocki managed to beat 3,000 Russians at the Battle of Olita on February 9.[36] Meanwhile, on February 7 Schulenburg had received word of Charles' crossing of the Vistula, and begun his march with the Saxon army in order to beat Rehnskiöld's smaller force near Poznań.[37] Rehnskiöld, however, did not wait to be defeated and instead strove to engage Schulenburg before the arrival of Augustus 8,000 men. By using a daring feint Rehnskiöld managed to lure Schulenburg into a more disadvantageous position near Wschowa (Fraustadt), where the two armies clashed on February 13.[38] Here, the Swedish general won a decisive victory killing or capturing up to 75% of Schulenburg's force.[39] Crippled by this setback, the main Saxon army had no choice but to retreat. The whole allied plan collapsed, as the opportunity for the allies to destroy Charles' army in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth with a sweeping movement from behind, vanished.[40]

Shortly after, on February 22, Carl Gustaf Dücker with 1,000 dragoons fought off 7,000 Poles and Russians under Christian Felix Bauer at Olkieniki near Vilnius, capturing and killing hundreds of allied troops. He also seized the Lithuanian capital and secured the Swedish connection to Livonia.[36] The situation in Grodno soon became unsustainable for the Russians as the soldiers began to die of starvation and disease.[41] In order to save his army, Peter I ordered his ally Ivan Mazepa and his Cossacks to carry out continuous harassing attacks on the back of the Swedes. Mazepa dispatched 14,000 men for this purpose. However, the Swedes countered the move, sending large contingents of troops from Grodno to assault Mazepa's nearby outposts. Mazepa sustained large casualties at both Nesvizh on March 23, where Johan Reinhold Trautvetter and his 500 Swedish dragoons killed and captured around 700 out of 1,200 Cossacks, and at Lyakhavichy in late March, where Carl Gustaf Creutz held 1,400 men trapped inside the fortress.[42]

On March 27, the Russians received word about the earlier disastrous defeat at Wschowa. Peter I realized that the chances of a combined attack on Charles were now minimal. He ordered Ogilvy to attempt an escape from the encirclement at Grodno and a retreat towards Brest-Litovsk.[43] Ogilvy carried out the order on April 4 and managed to break out unseen with his reduced army, leaving 8,000 men behind at Grodno who had died of starvation and sickness. Another 9,000 men were lost during the retreat as the Swedes pursued the Russians as far as Polesia, where they finally gave up the chase.[44][45] Mazepa met a similar defeat, as he sent 4,700 men in an attempt to save the Cossacks trapped inside Lyakhavichy. Instead these were annihilated in the battle of Kletsk on April 30, after which the garrison in Lyakhavichy surrendered to the Swedes on May 12 and the fortress was destroyed.[42] In total, almost 10,000 Cossacks were killed, out of the initial 14,000 who actively participated in the campaign.[42][46]

Aftermath

Charles had won one of his greatest victories at Grodno 1706, by simply cutting off his opponents' resources and supplies. Later, in a letter to his ally Frederick IV of Denmark, Peter I confirmed losses of up to 17,000 men during the encirclement and retreat.[47] After his pursuit of the Russian army, having chased them out of Lithuania, Charles saw his opportunity to march back to Poland in order to meet up with Rehnskiöld, in preparation for the invasion of Saxony. He arrived there in August 5.[48] Meanwhile, Schulenburg did what he could in an attempt to increase the Saxon army to measure the expected invasion from the Swedes, something which was proven close to impossible after the battle of Fraustadt.[49] In a last attempt to stop the invasion, Augustus II of Saxony offered Courland to Sweden and Lithuania to the newly crowned king Stanisław I of Poland. The generous offer was, however denied by Charles who crossed the Saxon border in September 5. As Saxony was close to defenseless, the Swedes could easily push away any resisting troops.[48] In September 19, they occupied the city of Leipzig which finally forced Augustus into unconditional peace under Swedish terms. Among other things, the traitor and second principal behind the Grodno campaign, Johann Patkul was turned into Swedish custody.[50]

Outcome

The campaign of Grodno proved disastrous to the allies who did not manage to attain any of their goals, while the Swedish army reached almost all of theirs; Stanisław Leszczyński was crowned king of Poland,[23] the Saxon and Russian armies in Poland were beaten,[51] and peace was forced upon Augustus who renounced all his claims to the Polish throne.[50] The two traitors and principal designers of the campaign, Johann Patkul and Otto Arnold von Paykull were also taken prisoner by the Swedes and executed in 1707.[50][52] However, the Great Northern War was far from being won. Charles reorganized his forces to march against his last remaining opponent, Peter the Great and the Tsardom of Russia. The Swedish invasion of Russia began in 1707 and ended with the disastrous Swedish defeat at Poltava. This marked a decisive turn in the war with Saxony and Denmark rejoining the alliance.[53]

| Battle | Swedish numbers | Coalition numbers | Swedish casualties | Coalition casualties | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gemauerthof | 7,000 | 14,000 | 1,900 | 5,000 | Swedish victory |

| Warsaw | 2,000 | 9,500 | 300 | 1,800 | Swedish victory |

| Mitau[22] | 900 | 10,000 | – | – | Russian victory |

| Praga | 1,000 | 5,000 | 150 | 250 | Swedish victory |

| Grodno | 34,000 | 41,000 | 3,000 | 15,000–17,000 | Swedish victory |

| Olita[36] | – | 3,000 | – | – | Swedish victory |

| Fraustadt | 10,000 | 20,000 | 1,500 | 15,000 | Swedish victory |

| Olkieniki[36] | 1,000 | 7,000 | – | 100+ | Swedish victory |

| Nesvizh[42] | 500 | 1,200 | 50 | 700 | Swedish victory |

| Lyakhavichy[42] | 2,000 | 1,400 | – | 1,400 | Swedish victory |

| Kletsk | 1,500 | 4,700 | 30 | 4,000 | Swedish victory |

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g Oskar Sjöström (2008). p. 69

- ^ a b c Alexander Gordon (1755). p. 216

- ^ Nicholas Dorrell (2009). p. 10

- ^ Nicholas Dorrell (2009). p. 11

- ^ a b Nicholas Dorrell (2009). p. 12

- ^ Nicholas Dorrell (2009). pp. 13–14

- ^ a b Nicholas Dorrell (2009). p. 15

- ^ Ulf Sundberg (2010). p. 220

- ^ Oskar Sjöström (2008). p. 40

- ^ Bengt Liljegren (2000). p. 47

- ^ Ulf Sundberg (2010). p. 223

- ^ Oskar Sjöström (2008). p. 54

- ^ Robert I Frost (2000). p. 268

- ^ Ulf Sundberg (2010). pp. 226–227

- ^ a b Oskar Sjöström (2008). p. 68

- ^ Ulf Sundberg (2010). p. 229

- ^ Oskar Sjöström (2008). p. 70

- ^ a b c Oskar Sjöström (2008). p. 72

- ^ Peter Ullgren (2008). p. 127

- ^ Oskar Sjöström (2008). p. 74

- ^ Oskar Sjöström (2008). p. 75

- ^ a b Knut Lundblad (1835). p. 391

- ^ a b Oskar Sjöström (2008). p. 84

- ^ Grimberg & Uddgren (1914). pp. 233–236

- ^ Oskar Sjöström (2008). p. 85

- ^ a b c d Oskar Sjöström (2008). pp. 86–87

- ^ Lars Ericson (2003). p. 274

- ^ Tom Gullberg (2008). p. 28

- ^ Grigorjev & Bespalov (2012). p. 165

- ^ Axel Svensson (2001). p. 89

- ^ Oskar Sjöström (2008). p. 88

- ^ Olle Larsson (2009). p. 148

- ^ Bengt Liljegren (2000). p. 134

- ^ a b Grigorjev & Bespalov (2012). p. 166

- ^ Axel Svensson (2001). p. 87

- ^ a b c d Axel Svensson (2001). p. 90

- ^ Oskar Sjöström (2008). p. 111

- ^ Oskar Sjöström (2008). pp. 150–157

- ^ Oskar Sjöström (2008). p. 245

- ^ Oskar Sjöström (2008). p. 263

- ^ Olle Larsson (2009). p. 149

- ^ a b c d e Håkan Henriksson (2009). pp. 6–12

- ^ Oskar Sjöström (2008). p. 276

- ^ Grigorjev & Bespalov (2012). p. 167

- ^ Ulf Sundberg (2010). p. 232

- ^ Oleg Bezverkhnii. Paragraph. 5

- ^ Peter Ullgren (2008). p. 293

- ^ a b Oskar Sjöström (2008). pp. 277–278

- ^ Oskar Sjöström (2008). p. 275

- ^ a b c Oskar Sjöström (2008). p. 280

- ^ Nicholas Dorrell (2009). p. 18

- ^ Peter Ullgren (2008). p. 128

- ^ Ulf Sundberg (2010). pp. 238–243

References

- Sjöström, Oskar. Fraustadt 1706, ett fält färgat rött. Historiska Media, (2009). ISBN 978-91-85507-90-0

- Dorrel, Nicholas A. The Dawn of the Tsarist Empire: Poltava & the Russian Campaigns of 1708–1709. Partizan Press, (2009). ISBN 978-1-85818-594-1

- Sundberg, Ulf. Sveriges krig: 1630–1814. Svenskt Militärhistoriskt Bibliotek, (2010). ISBN 978-91-85789-63-4

- Ullgren, Peter. Det stora nordiska kriget 1700–1721, en berättelse om stormakten Sveriges fall. Prisma, (2008). ISBN 978-91-518-5107-5

- Larsson, Olle. Stormaktens sista krig, Sverige och stora nordiska kriget 1700–1721. Historiska Media, (2009). ISBN 978-91-85873-59-3

- Grigorjev, Boris & Bespalov, Aleksandr. Kampen mot övermakten. Baltikums fall 1700–1710. Efron & Dotter, (2012). ISBN 978-91-85653-52-2

- Gullberg, Tom. Krigen kring Östersjön, Lejonet vaknar 1611–1660. Schildts, (2008). ISBN 978-951-50-1822-9

- Robert I. Frost. The Northern Wars: War, State and Society in Northeastern Europe, 1558–1721. Longman, (2000). ISBN 978-0-582-06429-4

- Svensson, Axel. Karl XII som fältherre. Svenskt Militärhistoriskt Bibliotek, (2001). ISBN 91-974056-1-2

- Liljegren, Bengt. Karl XII, en biografi. Historiska Media, (2000). ISBN 91-88930-99-8

- Ericson, Lars. Svenska slagfält. Wahlström & Widstrand, (2003). ISBN 91-46-21087-3

- Grimberg, Carl & Uddgren, Hugo. Svenska krigarbragder. P.A. Norstedt & Söner, (1914).

- Lundblad, Knut. Geschichte Karl des Zwölften Königs von Schweden, Band 1. Hamburg, (1835).

- Henriksson, Håkan. När kosackerna kom till Askersund. Aktstycket, (December 2009).

- Gordon, Alexander. The History of Peter the Great, Emperor of Russia: To which is Prefixed a Short General History of the Country from the Rise of that Monarchy: and an Account of the Author's Life, Volume 1. Aberdeen. (1755).