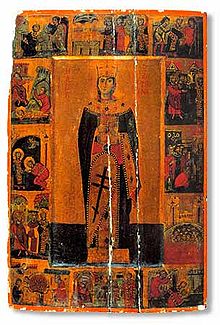

Catherine of Alexandria

Saint Catherine of Alexandria, also known as Saint Catherine of the Wheel and The Great Martyr Saint Catherine (Greek Template:Polytonic) is a Christian saint and martyr who is claimed to have been a noted scholar in the early 4th century. In the beginning of the fifteenth century, it was rumored that she had spoken to Saint Joan of Arc. The Orthodox Churches venerate her as a "great martyr", and in the Catholic Church she is traditionally revered as one of the Fourteen Holy Helpers.

What is told of Saint Catherine's life is mostly composed of legends which have many different variations, and have little historical basis. The most popular version is that Catherine was the daughter of Costus, governor of Alexandria. She announced to her parents that she would only marry someone who surpassed her in everything, such that "His beauty was more radiant than the shining of the sun, His wisdom governed all creation, His riches were spread throughout all the world."[1]

Life and legend

It is said that she visited her contemporary, the Roman Emperor Maximinus, and attempted to convince him of the error of his ways in persecuting Christians. She succeeded in converting his wife, the Empress, and many pagan wise men whom the Emperor sent to dispute with her, all of whom were subsequently martyred.[1] Upon the failure of the Emperor to win Catherine over, he ordered her to be put in prison; and when the people who visited her converted, she was condemned to death on the breaking wheel (an instrument of torture). According to legend, the wheel itself broke when she touched it, so she was beheaded.

In an elaboration of the legend, angels carried her body to Mount Sinai, where in the 6th century, the Eastern Emperor Justinian established Saint Catherine's Monastery, Mount Sinai, the church being built between 548 and 565 in Saint Katherine city, Egypt. Saint Catherine's Monastery survives, a famous repository of early Christian art, architecture and illuminated manuscripts that is open to visiting scholars still.

Her principal symbol is the spiked wheel, which has become known as the Catherine wheel, and her feast day is celebrated on 25 November by most Christian churches. However, the Russian Orthodox Church celebrates it on 24 November, because Empress Catherine the Great did not wish to share her patronal feast with the Leavetaking of the feast of the Presentation of the Theotokos. Because she was Catherine the Great's patron, the Catholic Church of St. Catherine, one of the first Catholic churches built in Russia, was named after Catherine of Alexandria.

Given the paucity of historical information, however, there is very little evidence to confirm any of these legends. Indeed, mentions of the legends themselves only began to appear centuries after her death.

Medieval cult

St. Catherine was one of the most influential saints in the religious culture of the late middle ages, and arguably considered the most important of the virgin-martyrs. Her power as an intercessor was reknown, and firmly established in most versions of her legend, in which she specifically entreats God at the moment of her death to answer the prayers of those who invoke her name. The development of her medieval cult was spurred by the reported rediscovery of her body around the year 800 at Mount Sinai, with hair still growing and a constant stream of healing oil emitting from her body.[4] There are a handful of pilgrimage narratives that chronicle the journey to Mount Sinai, most notably those of John Mandeville and Friar Felix Fabri.[5] However, the monastery at Mount Sinai was the best-known site of Catherine pilgrimage, but was also the most difficult to reach. The most prominent western shrine was the monastery in Rouen that claimed to house Catherine's fingers. It was not alone in the west, however, accompanied by many, scattered shrines and alters dedicated to Catherine, which existed throughout France and England. Some were better known sites, such as Canterbury and Westminster, which claimed a phial of her oil, brought back from Mount Sinai by Edward the Confessor.[6] Other shrines were the focus of generally local pilgrimage, many of which are only identified by brief mentions to them in various texts, rather than by physical evidence.[7]

St. Catherine also had a large female following, whose devotion was less likely to be expressed through pilgrimage. The importance of the virgin-martyrs as the focus of devotion and models for proper feminine behavior increased during the late middle ages.[8] Among these, St. Catherine in particular was used as an exemplar for women, a status which at times superseded her intercessory role.[9] Both Christine de Pizan and Geoffrey de la Tour Landry point to Catherine as a paradigm for young women, emphasizing her model of virginity and "wifely chastity."[10]

History and veneration

Historians such as Harold Thayler Davis believe that Catherine ('the pure one') may not have existed and that she was more an ideal exemplary figure than a historical one.[11] She did certainly form an exemplary counterpart to the pagan philosopher Hypatia of Alexandria in the medieval mindset; and it has been suggested that she was invented specifically for that purpose. Like Hypatia, she is said to have been highly learned (in philosophy and theology), very beautiful, sexually pure, and to have been brutally murdered for publicly stating her beliefs. Catherine is placed 105 years before Hypatia's death, although the first records mentioning her are much later.

Because of the fabulous character of her hagiography (the account of her martyrdom) and because of uncertainty about who she was, the Roman Catholic Church in 1969 removed her feast day from the Roman Catholic calendar of saints to be commemorated universally, wherever the Roman Rite is celebrated.[12] But she continued to be recognized as a saint of the Catholic Church, with a feast on November 25.[13] In 2002, her feast was restored to the Roman Catholic calendar of saints as an optional memorial, which may be celebrated throughout the Latin Church. The 1908 Catholic Encyclopedia describes the historical importance of the belief in her as follows:

Ranked with St Margaret and St Barbara as one of the fourteen most helpful saints in heaven, she was unceasingly praised by preachers and sung by poets. It is believed that Jacques-Benigne Bossuet dedicated to her one of his most beautiful panegyrics and that Adam of St. Victor wrote a magnificent poem in her honour: Vox Sonora nostri chori, etc. In many places her feast was celebrated with the utmost solemnity, servile work being suppressed and the devotions being attended by great numbers of people. In several dioceses of France it was observed as a Holy Day of Obligation up to the beginning of the seventeenth century, the splendor of its ceremonial eclipsing that of the feasts of some of the Apostles. Numberless chapels were placed under her patronage and her statue was found in nearly all churches, representing her according to medieval iconography with a wheel, her instrument of torture. Meanwhile, owing to several circumstances in his life, Saint Nicholas of Myra was considered the patron of young bachelors and students, and Saint Catherine became the patroness of young maidens and female students. Looked upon as the holiest and most illustrious of the virgins of Christ after the Blessed Virgin Mary, it was natural that she, of all others, should be worthy to watch over the virgins of the cloister and the young women of the world. The spiked wheel having become emblematic of the saint, wheelwrights and mechanics placed themselves under her patronage. Finally, as according to tradition, she not only remained a virgin by governing her passions and conquered her executioners by wearying their patience, but triumphed in science by closing the mouths of sophists, her intercession was implored by theologians, apologists, pulpit orators, and philosophers. Before studying, writing, or preaching, they besought her to illumine their minds, guide their pens, and impart eloquence to their words. This devotion to St. Catherine which assumed such vast proportions in Europe after the Crusades, received additional éclat in France in the beginning of the fifteenth century, when it was rumored that she had spoken to Joan of Arc and, together with St. Margaret, had been divinely appointed Joan's adviser.

References

- ^ a b c Self-Ruled Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America. Accessed 30 Dec 2006.

- ^ a b See her Patron Saints Index profile

- ^ a b See her Catholic Culture profile

- ^ S.R.T.O d'Ardeene and E.J. Dobson, Seinte Katerine: Re-Edited from MS Bodley 34 and other Manuscripts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981), xiv.

- ^ John Mandeville, The Travels of Sir John Mandeville (New York: Dover Publications Inc., 1964); Felix Fabri, The Wanderings of Felix Fabri (New York: AMS Press, 1971), 217.

- ^ Christine Walsh, "The Role of the Normans in the Development of the Cult of St. Katherine" in St. Katherine of Alexandria: Texts and Contexts in Western Medieval Europe eds. Jacqueline Jenkins and Katherine J. Lewis (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2003), 31; Katherine J. Lewis, "Pilgrimage and the Cult of St. Katherine of Alexandria in Late Medieval England" in St. Katherine of Alexandria: Texts and Contexts in Western Medieval Europe eds. Jacqueline Jenkins and Katherine J. Lewis (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2003),44.

- ^ Lewis, "Pilgrimage and the Cult of St. Katherine", 49-51.

- ^ John Bugge, Virginitas: An Essay in the History of the Medieval Ideal (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1975), 132; Katherine J. Lewis, The Cult of St. Katherine of Alexiandria in Late Medieval England (Rochester: The Boydell Press, 2000), 229; Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Alters: Traditional Religion in England c.1400-c.1580 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 174.

- ^ Katherine J. Lewis, "Model Girls? Virgin-Martyrs and the Training of Young Women in Late Medieval England" in Young Medieval Womeen eds. Katherine J. Lewis, Noel James Menuge and Kim M. Phillips (New York: St. Martin's PRess, 1999).

- ^ Christine de Pizan, The Treasure of the City of Ladies trans. by Sarah Lawson (New York: Penguin Books, 2003), 146; Christine de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies trans. by Rosalind Brown-Grant (New York: Penguin Books, 1999), 203; Rebecca Barnhouse, The Book of the Knight of the Tower (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 126, 193.

- ^ Harold Thayler Davis. Alexandria: The Golden City. (Principia Press of Illinois, 1957).

- ^ Calendarium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1969), p. 147

- ^ Martyrologium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2001 ISBN 88-209-7210-7)

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

See also

- Catherinettes

- Catherine wheel

- Saint Catherine of Alexandria, by Raphael

- Saint Catherine, by Caravaggio

- Catharina - Lunar crater named after St. Catherine

- Saint Catherine's Monastery, Mount Sinai

- Santa Catalina Island - California Channel Island named after St. Catherine

- Santa Catalina Mountains - A prominent mountain range north of Tucson, Arizona, United States was named after St. Catherine in 1697.

- Se Cathedral - dedicated to Saint Catherine

- Cartagena de Indias - Main Colombian city which Saint Catherine is patron.

- Santa Catarina - One of the tree states in south Brazil.

- St. Catherine Band Club [1]

- St. Catherine's Day

External links

- Pagbilao Church - Saint Catherine of Alexandria Church

- Iconographical Themes in Art - Saint Catherine of Alexandria

- Details of Saint Catherine's life - Saint Catherine Orthodox Church; includes a gallery of icons of the saint

- Feast of the Holy Great Martyr and Most Wise Catherine of Alexandria - Greek Orthodox Archdiocese

- St Catherine's church in Muhu island (Estonia)

- Representetions of Saint Catherine

- Fourteen Holy Helpers

- 287 births

- 305 deaths

- Ancient Roman women

- Christian folklore

- Eastern Orthodox saints

- Eastern Catholic saints

- Oriental Orthodox saints

- Roman Catholic saints

- Egyptian Roman Catholic saints

- Egyptian saints

- Saints of the Golden Legend

- 4th-century Christian martyr saints

- 3rd-century Romans

- 4th-century Romans

- 4th-century Christian female saints