Black City (Baku)

40°22′59″N 49°53′20″E / 40.383°N 49.889°E

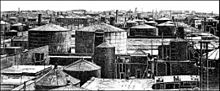

Black City (Azerbaijani: Qara Şəhər) is the general name for the southeastern neighbourhoods of Baku, which once formed its suburbs. In the late 19th and early 20th century it became the main location for Azerbaijan's oil industry, and the area's name derives from the smoke and soot of the factories and refineries.

History

[edit]

Background

[edit]Baku was incorporated into the Russian Empire in 1813 under the Treaty of Gulistan. At that time it was a small town of 10,000 inhabitants.[1] The world's first oil well was drilled at Baku in 1847/1848, and was soon followed by many more.[2] The first oil refining plants were built in 1859 in the city suburbs.[1] By the 1860s the Baku fields accounted for 90% of the world's oil supply.[2] Industrial buildings came to occupy large sections of the city. Plants and factories were hazardous to the population due to air pollution from their smokestacks. Public pressure forced the provincial authorities to consider developing a separate industrial zone. In 1870, the authorities suggested that pasture lands to the east of the city be allotted for construction of oil refineries.[3] By 1872 there were almost sixty refineries in Baku producing kerosene. A law was passed prohibiting the construction of any new plants in the city, and allocating a new district outside the city limits for refineries.[4]

Foundation and growth

[edit]

By 1874 there were 123 refineries in what would become known as "Black City".[4] The refinery district was about 8 miles (13 km) from the shipping ports.[5] An industrial area plan was completed in 1876. Some of the farms and pastures of the neighbouring village of Keshla were zoned to accommodate replacements for factories that had been dismantled in the city. The new industrial zone was 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) from residential areas. To prevent further pollution, the new zoning law prohibited oil refineries from being built within the residential area.[3] By 1880, there were 118 industrial businesses functioning in the Black City area.[3]

Most of the Baku oil workers lived in the area. The suburb also accommodated oil companies offices, workshops and housing for the associated labourers. Living conditions were very bad in contrast to conditions in Baku proper.[6] Wealthy residents chose to settle in the city centre, where oil extraction and refinery were forbidden.[7] The area came to be known as Black City (Russian: Чёрный город) because of the black smoke and soot coming from the factories and oil refineries. A Turkish traveller who visited Black City in 1890 described it as follows:

"Everything is black; the walls, the earth, the air, and the sky. You can feel the oil and inhale the fumes, and reek chokes you. You walk among clouds of smoke which cover up the sky."[8]

In 1878, the Nobel Brothers built the first oil pipeline in the Russian Empire. It was 5.6 miles (9.0 km) long and 2 inches (51 mm) in diameter, and could deliver almost 10,000 barrels per day.[9] Crude was pumped from the oil wells to central storage tanks at Balakhani, and from there to the refineries. The cost of construction was recovered in the first year of operation.[10] Other companies soon followed the Nobels' lead.[11]

The older Nobel brothers founded the Nobel Brothers Oil Extraction Partnership in 1879, and were soon in control of 75% of the oil industry in Baku.[1] As of October 1885, most of the Baku refineries were in Black City. The oil was moved by pipes 4 to 6 inches (100 to 150 mm) in diameter resting on the ground and conforming to its curvature. There were twelve reservoirs in all, two owned by the Nobels. The smaller refiners had to make use of the reservoirs owned by the larger firms.[12]

Later developments

[edit]Balakhany was an oil-rich area 9 miles (14 km) from Baku city.[13] The Swedish explorer Sven Hedin visited the Balakhany oil fields in 1890. There were then 410 wells, of which the Nobels owned 116, mostly 720 to 900 feet (220 to 270 m) deep. One of the Nobel wells gushed 150,000 poods per day, and the Nobels pumped 230,000 poods of crude each day to Black City through two lines, the largest with a diameter of 24 inches (610 mm). The Nobels produced 60,000 poods of refined oil per day.[14][a]

When Black City began growing beyond its borders, oil industrialists started to look for new convenient areas to serve their needs. Soon a new industrial area to the east of Black City emerged and became known as White City. By the end of 1902, up to 20 more large oil refineries and oil-related trade businesses were built here such as Mantashev and Co., Caspian–Black Sea Society and Shibayev's Chemical Plant.[3] Unlike Black City, White City accommodated more modern and better functioning refineries and therefore, the area was not as polluted.[13] In 1882–1883, the Nobel brothers founded an industrial community on the border of Black City and White City called Villa Petrolea.[15] By 1905, most oil refineries of Baku were located there.[16]

James Dodds Henry wrote in 1905 that Black City and Bibi-Heybat were the only "black spots" of Baku.[13] Baku was one of the toughest cities in the Russian Empire. As a young man Joseph Stalin spent time there in the 1900s, where he allied himself with organized crime gangs against the oil tycoons. It was said that some wasteland in Black City was controlled by a gang. Stalin "made an agreement with the gang only to let through Bolsheviks, not Mensheviks. The Bolsheviks had special passwords." Another story says that Stalin was behind the profitable kidnapping of the oil tycoon Musa Nagiyev.[17] Stalin also organized strikes in the oil fields, and the Bolsheviks distributed their newspaper Iskra via the oil shipping network.[5]

Planning

[edit]

The plan for Black City marked the first time in the history of Russian urban planning that the design of an urban area was based on the principle of symmetrical construction. The blocks in Black City were laid out in a rectangular grid with wide, straight roads. One of the roads ended at a square which overlooked the area's numerous wharfs. This was quite different from the layout of downtown Baku, with its small blocks and a network of narrow streets. The industrial zone grew from south to north and eventually occupied the rural area that separated Black City from Balakhany. After draining the coastal marshes and reclaiming the land, the coastal area of Black City began to be used as well.[3]

In the decades that followed its initial construction, the road plan of Black City did not change. The built-up area was renovated and replaced according to technological requirements of the time.[3]

Current situation

[edit]As of 1993, the Baku region only produced about 2% of the crude oil in the countries of the former Soviet Union, mostly from offshore wells.[18] Black City still contains a large park that was established by Ludvig and Robert Nobel.[19] However, a 2009 book described a desolate scene of derelict oil wells, garbage and pollution in the vicinity of Black City, with no trace of greenery.[20] The Villa Petrolea, formerly the residence of the Nobel brothers, was empty and derelict[21] before the start of a restoration programme, organised between 2004 and 2007 by a public organization named the Baku Nobel Heritage Fund. The reconstructed Villa Petrolea now houses the Baku Nobel Oil Club, an International Conference Hall and the Nobel Brothers Museum, the first Nobel museum outside Sweden.[22]

The area of Black City is currently under the jurisdiction of the Xətai raion. The district is served by the Şah İsmail Xətai (or Khatai) station of the Baku Metro system.

Future plans

[edit]A masterplan for the redevelopment of a 221 hectares of former industrial land as "White City" foresees the construction of 10 urban neighbourhoods to house around 50,000 residents and to create work space for 48,000 jobs.[23] The project is being implemented jointly by Atkins and Foster and Partners.[24][25][26] There will be 39 hectares of landscaped parks and gardens, roughly 1/3 the total area of Hyde Park, London, and plans suggest provision of 40,000 car parking places.[27] The waterfront will extend Baku Boulevard by another 1.3 km and plans to include a 65m ferris wheel, a 4-hectare fountain garden and a whole series of 'landmark' buildings, to ensure the environment does not feel too homogenous.[28] There should be a vast entertainment centre, mall, and two new metro stations: one central with exits on Nobel pr and another interchange station on the northern edge of the redevelopment at Babek pr.[29]

Cultural impact

[edit]- White and Black Cities, a short film (1908). The film includes scenes of a spectacular oil well fire, one of several such films recording the drama of the Baku oil industry. At the time such events were seen as inevitable byproducts of progress.[30]

- The Black City, a novel by Boris Akunin (2012)

Notes and references

[edit]- Notes

- ^ A "pood" was a Russian unit of weight, about 36.11 pounds, so the Nobel's daily refined petroleum output in 1890 would have been 60,000x36.11 pounds, or 2,166,600 pounds (982,800 kg)

- Citations

- ^ a b c Dumper & Stanley 2007, p. 64.

- ^ a b Farndon 2012, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f Fatullayev 1978.

- ^ a b Sokolov 2002, p. 26.

- ^ a b Black 2012, p. 80.

- ^ Heyat 2002, p. 47.

- ^ Swietochowski 2004, p. 21.

- ^ Black 2004, p. 100.

- ^ Vassiliou 2009, p. 98.

- ^ Henry 1905, p. 73-74.

- ^ Henry 1905, p. 88.

- ^ Russian Petroleum - Bradstreet's.

- ^ a b c Henry 1905, p. 8.

- ^ Hedin 1926, p. 528.

- ^ Villa Petrolea - Our Baku.

- ^ Henry 1905, p. 14.

- ^ Montefiore 2008, p. 187.

- ^ Kaufman 1993, p. 948.

- ^ Beene 2011, p. 357.

- ^ Agbahowe 2009, p. 404.

- ^ Asbrink 2002, pp. 56–59.

- ^ "Baku Nobel Heritage Fund (BNHF); Baku Nobel Oil Club (BNOC)". Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- ^ White City Facts & Figures

- ^ Baku White City Urban Development Project.

- ^ "Atkins White City plans". Archived from the original on 2014-06-27. Retrieved 2014-04-17.

- ^ White City website

- ^ White City Facts & Figures

- ^ White City Facts & Figures

- ^ White City Facts & Figures

- ^ Murray & Heumann 2009, p. 25.

- Sources

- Agbahowe, Nathaniel U. (2009-01-30). Wake Up Africa!. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4389-1467-1. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- Asbrink, Brita (Summer 2002). "The Nobels in Baku: Swedes' Role in Baku's First Oil Boom". Azerbaijan International. 10 (2). Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- "Baku White City Urban Development Project" (PDF). Islamic Development Bank. June 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-11. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- Beene, Gary (2011-07-25). The Seeds We Sow: Kindness That Fed a Hungry World. Sunstone Press. ISBN 978-1-61139-012-4. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- Black, Brian C. (2012-03-22). Crude Reality: Petroleum in World History. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-4422-1611-2. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- Black, Edwin (2004-11-11). Banking on Baghdad: Inside Iraq's 7,000-Year History of War, Profit, and Conflict. John Wiley & Sons. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-471-70895-7. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- Dumper, Michael R. T.; Stanley, Bruce E. (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-919-5. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- Farndon, John (2012-01-16). DK Eyewitness Books: Oil. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-7566-9898-0. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- Fatullayev, Shamil (1978). ГРАДОСТРОИТЕЛЬСТВО БАКУ: XIX - начала XX веков [BAKU URBAN PLANNING: 19th - early 20th centuries] (in Russian). Institute of Architecture and Art of the Academy of Sciences of Azerbaijan SSR (IAiI). Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- Hedin, Sven (1926). My Life As an Explorer. Asian Educational Services. p. 528. ISBN 978-81-206-1057-6. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- Henry, James Dodds (1905). Baku: an eventful history. A. Constable & Co., ltd.

- Heyat, Farideh (2002). Azeri Women in Transition: Women in Soviet and Post-Soviet Azerbaijan. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7007-1662-3. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- Kaufman, Richard F. (1993). The Former Soviet Union in Transition. M.E. Sharpe. p. 948. ISBN 978-1-56324-318-9. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- Montefiore, Simon Sebag (2008-10-14). Young Stalin. Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4000-9613-8. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- Murray, Robin L.; Heumann, Joseph K. (2009-01-08). Ecology and Popular Film: Cinema on the Edge. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-7678-9. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- "Russian Petroleum". Bradstreet's Weekly: A Business Digest. Bradstreet Company. 1886. p. 275. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- Sokolov, Vasily Andreevich (2002-03-01). Petroleum. The Minerva Group, Inc. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-89875-725-5. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- Swietochowski, Tadeusz (2004-06-07). Russian Azerbaijan, 1905-1920: The Shaping of a National Identity in a Muslim Community. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52245-8. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- Vassiliou, Marius (2009-03-02). Historical Dictionary of the Petroleum Industry. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6288-3. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- ""Вилла Петролеа" - "Villa Petrolea" - поселок служащих (Черный город,Баку)" ["Villa Petrolea" town employees (Black City, Baku)]. Our Baku (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2012-05-07. Retrieved 2013-02-14.