Chert

Chert (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈtʃɜːrt/) is a fine-grained silica-rich microcrystalline, cryptocrystalline or microfibrous sedimentary rock that may contain small fossils. It varies greatly in color (from white to black), but most often manifests as gray, brown, grayish brown and light green to rusty red; its color is an expression of trace elements present in the rock, and both red and green are most often related to traces of iron (in its oxidized and reduced forms respectively).

Occurrence

Chert occurs as oval to irregular nodules in greensand, limestone, chalk, and dolostone formations as a replacement mineral, where it is formed as a result of some type of diagenesis. Where it occurs in chalk or marl, it is usually called flint. It also occurs in thin beds, when it is a primary deposit (such as with many jaspers and radiolarites). Thick beds of chert occur in deep geosynclinal deposits. These thickly bedded cherts include the novaculite of the Ouachita Mountains of Arkansas, Oklahoma, and similar occurrences in Texas in the United States. The banded iron formations of Precambrian age are composed of alternating layers of chert and iron oxides.

Chert also occurs in diatomaceous deposits and is known as diatomaceous chert. Diatomaceous chert consists of beds and lenses of diatomite which were converted during diagenesis into dense, hard chert. Beds of marine diatomaceous chert comprising strata several hundred meters thick have been reported from sedimentary sequences such as the Miocene Monterey Formation of California and occur in rocks as old as the Cretaceous.[1]

Terminology: "chert", "chalcedony" and "flint"

There is much confusion concerning the exact meanings and differences among the terms "chert", "chalcedony" and "flint" (as well as their numerous varieties). In petrology the term "chert" is used to refer generally to all rocks composed primarily of microcrystalline, cryptocrystalline and microfibrous quartz. The term does not include quartzite. Chalcedony is a microfibrous (microcrystaline with a fibrous structure) variety of quartz.

Strictly speaking, the term "flint" is reserved for varieties of chert which occur in chalk and marly limestone formations.[2][3] Among non-geologists (in particular among archaeologists), the distinction between "flint" and "chert" is often one of quality - chert being lower quality than flint. This usage of the terminology is prevalent in America and is likely caused by early immigrants who imported the terms from England where most true flint (that found in chalk formations) was indeed of better quality than "common chert" (from limestone formations).

Among petrologists, chalcedony is sometimes considered separately from chert due to its fibrous structure. Since many cherts contain both microcrystaline and microfibrous quartz, it is sometimes difficult to classify a rock as completely chalcedony, thus its general inclusion as a variety of chert.

Chert and Precambrian fossils

The cryptocrystalline nature of chert, combined with its above average ability to resist weathering, recrystallization and metamorphism has made it an ideal rock for preservation of early life forms.[4]

For example:

- The 3.2 Ga chert of the Fig Tree Formation in the Barbeton Mountains between Swaziland and South Africa preserved non-colonial unicellular bacteria-like fossils.[5]

- The Gunflint Chert of western Ontario (1.9 to 2.3 Ga) preserves not only bacteria and cyanobacteria but also organisms believed to be ammonia-consuming and some that resemble green algae and fungus-like organisms.[6]

- The Apex Chert (3.4 Ga) of the Pilbara craton, Australia preserved eleven taxa of prokaryotes.[7]

- The Bitter Springs Formation of the Amadeus Basin, Central Australia, preserves 850 Ma cyanobacteria and algae.[8]

- The Devonian Rhynie chert (400 Ma) of Scotland has the oldest remains of land flora, and the preservation is so perfect that it allows cellular studies of the fossils.

Prehistoric and historic uses

In prehistoric times, chert was often used as a raw material for the construction of stone tools. Like obsidian, as well as some rhyolites, felsites, quartzites, and other tool stones used in lithic reduction, chert fractures in a Hertzian cone when struck with sufficient force. This results in conchoidal fractures, a characteristic of all minerals with no cleavage planes. In this kind of fracture, a cone of force propagates through the material from the point of impact, eventually removing a full or partial cone; this result is familiar to anyone who has seen what happens to a plate-glass window when struck by a small object, such as an airgun projectile. The partial Hertzian cones produced during lithic reduction are called flakes, and exhibit features characteristic of this sort of breakage, including striking platforms, bulbs of force, and occasionally eraillures, which are small secondary flakes detached from the flake's bulb of force.

When a chert stone is struck against an iron-bearing surface sparks result. This makes chert an excellent tool for starting fires, and both flint and common chert were used in various types of fire-starting tools, such as tinderboxes, throughout history. A primary historic use of common chert and flint was for flintlock firearms, in which the chert striking a metal plate produces a spark that ignites a small reservoir containing black powder, discharging the firearm.

In some areas, chert is ubiquitous as stream gravel and fieldstone and is currently used as construction material and road surfacing. Part of chert's popularity in road surfacing or driveway construction is that rain tends to firm and compact chert while other fill often gets muddy when wet. However, where cherty gravel ends up as fill in concrete, the slick surface can cause localized failure.

Chert has been used in late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century headstones or grave markers in Tennessee and other regions.

Varieties of chert

There are numerous varieties of chert, classified based on their visible, microscopic and physical characteristics.[9][10] Some of the more common varieties are:

- Flint is a compact microcrystalline quartz. It is found in chalk or marly limestone formations and is formed by a replacement of calcium carbonate with silica. It is commonly found as nodules. This variety was often used in past times to make bladed tools.

- "Common chert" is a variety of chert which forms in limestone formations by replacement of calcium carbonate with silica. This is the most abundantly found variety of chert. It is generally considered to be less attractive for producing gem stones and bladed tools than flint.

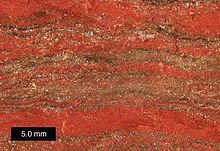

- Jasper is a variety of chert formed as primary deposits, found in or in connection with magmatic formations which owes its red color to iron(III) inclusions. Jasper frequently also occurs in black, yellow or even green (depending on the type of iron it contains). Jasper is usually opaque to near opaque.

- Radiolarite is a variety of chert formed as primary deposits and containing radiolarian microfossils.

- Chalcedony is a microfibrous quartz.

- Agate is distinctly banded chalcedony with successive layers differing in color or value.

- Onyx is a banded agate with layers in parallel lines, often black and white.

- Opal is a hydrated silicon dioxide. It is often of a Neogenic origin. In fact is not a mineral (it is a mineraloid) and it is generally not considered a variety of chert, although some varieties of opal (opal-C and opal-CT) are microcrystaline and contain much less water (sometime none). Often people without petrological training confuse opal with chert due to similar visible and physical characteristics.

- Magadi-type chert is a variety that forms from a sodium silicate precursor in highly alkaline lakes such as Lake Magadi in Kenya.

- Porcelanite is a term used for fine-grained siliceous rocks with a texture and a fracture resembling those of unglazed porcelain.

- Siliceous sinter is porous, low-density, light-colored siliceous rock deposited by waters of hot springs and geysers.

Other lesser used terms for chert (most of them archaic) include firestone, silex, silica stone, chat, and flintstone.

See also

- Petrology

- Eolith

- Nodule (geology) not to be confused with Concretion

- Obsidian

- Opal

- Whinstone

- Archaeology

- Clovis Points, archaeological artefacts of the Clovis culture in New Mexico

- Piatra Tomii, a prehistoric chert mine in Alba County, Romania

References

- ^ *Sam Boggs, Jr., "Principles of Sedimentology and Stratigraphy", Prentice Hall, 2006, 4th Ed., ISBN 0-13-154728-3

- ^ George R. Rapp, "Archaeomineralogy", 2002. ISBN 3-540-42579-9

- ^ Barbara E. Luedtke, "The Identification of Sources of Chert Artifacts", American Antiquity, Vol. 44, No.4 (Oct., 1979), 744-757.

- ^ THE EARLIEST LIFE: Annotated listing

- ^ Fig Tree Formation of South Africa

- ^ Gunflint chert

- ^ BIOGENICITY OF MICROFOSSILS IN THE APEX CHERT

- ^ Cyanobacertial fossils of the Bitter Springs Chert, UMCP Berkley

- ^ W.L. Roberts, T.J. Campbell, G.R. Rapp Jr., "Encyclopedia of Mineralogy, Second Edition", 1990. ISBN 0-442-27681-8

- ^ R.S. Mitchell, "Dictionary of Rocks", 1985. ISBN 0-442-26328-7

- Photo & note re: Fig Tree Formation

- Microphotographs of Fig Tree fossils

- Schopf, J.W. (1999) Cradle of Life: The Discovery of Earth's Earliest Fossils, Princeton University Press, 336 p. ISBN 0-691-00230-4

- An Archaeological Guide To Chert Types Of East-Central Illinois