Church of Notre-Dame de Dives-sur-Merent

View from the southeast in 2020. | |

| |

| 49°17′7.1″N 0°5′49.0″W / 49.285306°N 0.096944°W | |

| Location | Dives-sur-Mer, Calvados France |

|---|---|

| Type | Church |

| Material | Limestone and Late Gothic flamboyant |

| Completion date | 1067 |

| Restored date | 2010 |

| Dedicated to | Virgin Mary |

Notre-Dame de Dives-Sur-Mer church is a Catholic building in the French commune of Dives-sur-Mer, in the Calvados department of the Normandy region. It was the site of a major pilgrimage that lasted until the Wars of Religion and the destruction of a devotional object, a Christ Saint-Sauveur, found by fishermen in the 11th century. The pilgrimage then resumed until the French Revolution.

Although the current building still contains elements dating back to the 11th century, and has suffered severe damage over the centuries, it is in relatively good condition thanks to successive restoration campaigns, the most recent dates from the early 21st century. According to Arcisse de Caumont,[1] it is "the most remarkable monument in Dives". It has been listed as a historic monument since 1888.[2] A number of furniture items have also been listed.

Few of the church's old stained-glass windows have survived, although at the end of the 20th century, a stained-glass panel from the 14th century was found and purchased by the commune with the help of the French government. The building has also preserved some remarkable marine graffiti on its walls, dating from the 15th to the early 20th centuries: the collection of graffiti, exceptional since there are over 400 of them, makes it possible to study both marine and river ships, as well as many aspects, including religious ones of the life of the community present in the commune for over more than five centuries.

Location[edit]

The church is located in the commune of Dives-sur-Mer, rue Hélène Boucher, in the heart of the old village and in the eastern part of the town, in the French department of Calvados. It is set back from the three main roads that run through the area. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the church was still surrounded by a cemetery.[3]

History[edit]

From its origins to the 13th century, a parish church whose development was linked to a pilgrimage.[edit]

The site has had a place of worship since at least Carolingian times, and even as early as the 6th or 7th centuries.[4] Dives depend on Jumièges Abbey from the 9th century.[5]

Fishermen discovered the statue of Christ Saint-Sauveur on April 6, 1001, according to the traditional date. The cult, however, is more recent.[6] After fishing, one of the men grazes the statue with an axe, causing it to bleed.[7] The cross was discovered three years later in the sea.[8] The statue would have been the subject of a dispute between sailors from Dives and Cabourg,[9] having been found in the waters of the latter parish; the statue, after being thrown into the estuary on the advice of the ecclesiastical authorities, then washed up on the Dives shore.[7] This statue may have been linked to Nicomedes, who sculpted several effigies, or to a cult building destroyed by marine erosion or from a sunken ship.[10] Saint-Sauveur was the name of the village until early modern times.[11] The building is mentioned in a text by Duke Richard II dated 1025.[6]

The church houses the relic, and the village is a place of pilgrimage that generates income.[10] This pilgrimage takes place twice a year, from Pentecost to Trinity Sunday, and in August.[5] It is based on the legend of Christ the Savior. Pilgrims enter through a portal reading the legend of Christ the Savior in the historiated keystones. The pilgrimage's purpose was not only to rescue pilgrims at sea, but also to fight epidemics and save their souls.[12] Access was via the south portal.[13]

The oldest parts of the current building date back to the 11th century, although it is not known when the first stone was laid, probably before.[14] Tradition attributes its construction to William the Conqueror, as early as 1067,[15] just after the conquest of England following the Battle of Hastings. Better evidenced, a charter from Guillaume de Breteuil dating from the end of the 11th century specifies that the donor granted Troarn Abbey a plot of land to extend the church. The extension of the building is thought to date from the late 11th and early 12th centuries.[16] Guillaume de Breteuil died in 1103.[17]

After the conquest of England, the fiefdom of Dives became part of the Abbey aux Hommes de Caen, whose rights were shared with the Abbey Saint-Martin de Troarn from 1066.[18] The rights of the Caen abbey were confirmed between 1066 and 1077.[18] The division between the two abbeys was confirmed by Odo between 1079 and 1083, as high dignitary of the duchy and not as bishop.[19] Odon's charter describes the building as an "old chapel".[16] The Abbaye aux Dames owns the tithe of Dives.[19] The Abbot of Caen collects tithes. He also collects tolls on captured whales and rights to salt produced.[19] The Saint-Martin de Troarn abbey owns the rights to the Dives church, the right to appoint a priest and the cemetery.[20]

Dives benefited from its connections with England.[21] A priory was founded in the 12th century, at an unknown date,[16] perhaps as a result of the success of the pilgrimage, with an unknown location.[22] In 1908, Abbé Bourdier mentions a period between 1179 and 1203 for the founding of this priory.[23] Some believe that the remains of the former priory, fortified at the beginning of the 15th century, are located opposite the church. The building was sold at the beginning of the 18th century.[24] According to Carpentier, this location is part of a local tradition, and it may simply be located within the church.[3][25]

The Romanesque extension to the church may date from this period. A document in the Saint-Martin de Troarn chartrier indicates that the donor's name, Durand, may apply to an abbot in office from 1059 to 1088, or to another in office from 1179 to 1203. Carpentier leans towards a dating in the last quarter of the 12th century.[26]

After the conquest of Normandy by Philippe Auguste, Dives became part of the royal domain, and was managed as a fiefferme; the lords of the estuary chose the English side, so the domains were handed over to loyal followers of the new power.[27] Around 1280, the fiefferme was attributed to the abbot of Saint-Étienne.[28]

From the 15th to the 18th century, between renovations and misfortunes[edit]

Expansion continued in the 14th and 15th centuries in Radiant Gothic style,[8] particularly in the nave.[29] The reconstruction of the building begins with the choir and extends up to the first two bays of the nave.[1] The transept and the upper part of the tower were also rebuilt.[11] The statue of the Holy Savior is placed in a high chapel and watched over by three monks provided with rooms.[30][31]

The Hundred Years' War caused serious damage to the church, which was "devastated".[15] Information on the Hundred Years' War is scarce.[32] English troops devastated the town in 1362 and 1410, and there was even a battle in 1443 that ended in a fire.[22] Construction of the church was delayed, especially as the Black Death affected the region. The Little Ice Age reached its zenith in 1380.[33] Caen was occupied in 1417 following a siege of the city.[34]

After 1417, the coastal areas were occasionally ravaged by English and French troops, despite the establishment of a "sea watch".[32] The watch was probably kept from the church tower.[35] The war disrupted trade and the church's construction was halted.[35] The church may have been destroyed, which explains the building's construction phases.[34]

Work was also carried out in the 16th century,[8] in Flamboyant Gothic style.[22] The destruction of the statue of Christ Saint-Sauveur, "a large worm-eaten crucifix" according to Théodore Beza,[36] is attributed to Admiral de Coligny's Huguenots in 1562,[30] stationed in the town awaiting English aid[22] after having sacked Troarn Abbey.[36] This episode took place at the start of the Wars of Religion.[36] A fire is said to have left its mark on the bell tower.[37]

A copy of the statue of Christ Saint-Sauveur was made in the 17th century and placed in the north transept[30] after having been deposited in the apsidal chapel of the Virgin.[38] The pilgrimage no longer drew large crowds.[22] According to Carpentier, the decline in pilgrimage had more to do with changing mentalities, the Catholic Reformation and economic changes from the 17th century onwards.[36] The town declined economically and demographically until the 19th century.[39] The high chapel is still mentioned in the early eighteenth century.[40]

From the French Revolution to the 21st century[edit]

Parish priest Perrin took his oath to the Constituent, then emigrated in 1792. He was replaced by a juring priest.[41] The church was looted in 1793: the bells narrowly escaped being melted down, but the silver treasure (representing 5.6 kg, or 12.34 lbs) was not so lucky.[41] The statue of the Saint-Sauveur was hidden by a local resident for the duration of the French Revolution.[41] The church became a temple of Reason in August 1793.[41]

The church was restored to worship in 1802, following the Concordat, and the parish had to rent the presbytery, which had been sold,[42] to accommodate the parish priest. Pilgrimages stopped[30] but resumed in 1812 with a new stained glass window,[42] and the reinstallation of the statue of Christ.[43] A single parish priest officiated in Dives and Cabourg in 1825; a house had to be acquired in the late 1820s to serve as a presbytery, but this was not completed until 1834. Work on the presbytery came up some forty years later.[44]

Restoration work began in 1842 and continued until the present day. However, the upper chapel was destroyed in the 1850s, but the building was recognized "for its heritage, architectural and historical value".[43] The building was listed as a historic monument on May 4, 1888.[2][14]

The medieval stained-glass windows were replaced in the second half of the 19th century, and the new glasswork was restored after the Second World War.[45] Work has also been carried out by the municipality since the late 20th and the beginning of the 21st centuries.[4] Since the 1990s, the church has been the subject of a major restoration campaign. A new campaign began in 2012 and was completed in 2014 with the restoration of the lantern tower and transept.[3] Restoration work has continued since the 2010s, in particular on the nave bays, the stained glass windows (thanks in part to a donation from a private individual)[46] and certain items of furniture.[3] The building remains fragile, as the sea air is eroding its sculptures.[47]

The building is used by the parish of Saint Sauveur de la Mer, created in 1997 and comprising the communes of Dives-sur-Mer and Houlgate. A statue of Saint Sauveur was donated to the building in 2001.[48] Since 2017, there has been only one priest for three parishes (Saint Sauveur de la Mer, Notre Dame des Fleurs and La Trinité des Monts).[49]

Description[edit]

Architecture[edit]

General features[edit]

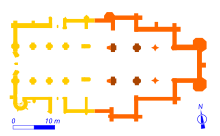

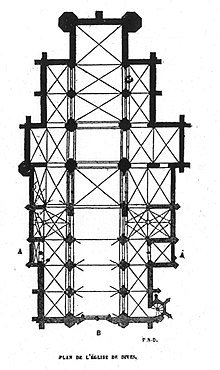

The church is built in limestone.[50] It is oriented and shaped like a Latin cross.[3]

The building comprises a nave and two aisles. There are two porches to the north and south, allowing two chapels to be placed on either side. The transept also retains two chapels. The chevet is flat, with a building behind it, possibly a sacristy.[3]

The church at Dives is "strangely similar to its English contemporaries", and out of all proportion to the size of the old village.[51] The church features Romanesque elements from the 11th century, with interlaced capitals at the transept crossing of the pre-Romanesque section. The transept and apse were enlarged in the 12th century, followed by the flamboyant Gothic style of the 14th and 15th centuries. The 14th-century reconstruction saw the addition of the aisled choir, the transept, the upper part of the square tower and the eastern bay.

In the early 1990s, the church was described as "surrounded by yew trees".[51] The remains of the gateway to the cemetery[51] on the north side of the building, feature shields carved on the two pillars, one better preserved than the other.[52]

-

North-west facade.

North-west facade. -

Southwest facade of the building.

-

Southwest facade.

Southwest facade. -

Building's southeast facade.

Building's southeast facade. -

Blason sur les vestiges du portail nord d'accès au cimetière.

Blason sur les vestiges du portail nord d'accès au cimetière.

[edit]

The western door is "a true masterpiece of sculpture" and was fitted with a porch that has now disappeared.[1] The building retains a pediment added in the 18th century,[43] with the inscription "le temple de Dieu est sainct" (the temple of God is holy) in a title block.[3] The monumental portal features a canopied Virgin and Child, and two other canopied statues of St. Peter and St. John the Baptist. The tympanum has no sculptures. The western facade features a polygonal tower.[3]

The first four bays of the nave were not completed until the late 15th or early 11th century,[32] along with the aisles and side chapels, the two side porches and the stair turret. The square tower was used as a lookout during the Hundred Years' War. The first bays of the nave are covered with a wooden ceiling.[34]

Two side porches, one opposite the other, were used for "the entrance and exit of the faithful".[1] The porch on the south facade has two levels, and the portal features a semicircular arch.[3] The charters were kept above the southern porch and above the baptismal font.[25]

-

Northern porch.

Northern porch. -

South gate.

South gate. -

18th-century pediment.

18th-century pediment. -

Mullioned windows on the north facade.

Mullioned windows on the north facade. -

North chapel, with the remains of the rooms used by the monks responsible for guarding the statue.

North chapel, with the remains of the rooms used by the monks responsible for guarding the statue. -

South chapel, with the chartrier in the upper section.

South chapel, with the chartrier in the upper section.

The north porch housed the monks' two-storey bedrooms and the upper chapel, reserved for clerics.[25] A fireplace has been preserved.[1][31] The building also retains mullioned windows in the north aisle, vestiges of the monks' bedrooms.[38]

Upper chapel[edit]

The rood screen, which delimited the upper chapel, was located on "the two bays preceding the transept"[1] and in front of the choir,[3] the fourth bay of the nave.[1] In the first third of the 19th century, Arcisse de Caumont describes the reliefs present at the time: on one of the arcades the story of the statue of Christ Saint-Sauveur was told, on another a ship with sailors was engraved, another a "figure of St-Sauveur crucified in relief" and on a fourth a construction scene with carpenters.[1] The building retains keystones from the 14th or 15th century, evoking the discovery of the statue.[11] These keystones were located in the two bays before the choir, which contained the upper chapel[53] and were reintegrated into the building in 1886 thanks to the efforts of Léon Le Rémois,[54] antique dealer and owner of the Hotel Guillaume le Conquérant.[55] Among the items preserved are a keystone with a text recounting the legend of the statue's rediscovery, another depicting a boat with sailors, and a third adorned with an angel.[54] These keystones may have been painted.[56]

-

Keystones in the rood screen.

Keystones in the rood screen. -

Keystone with part of the text of the legend of the discovery of Christ the Savior.

Keystone with part of the text of the legend of the discovery of Christ the Savior.

Lantern tower and upper parts of the building[edit]

The lantern tower has two levels, the second features a window.[3] A "gargoyle path" provided access to the roof of the building, from a staircase located to the southwest. The building can also be surrounded[57] by a covered walkway.[37] The gargoyle path was once protected by a baluster linking the bell towers.

At the transept intersection, the building retains the vestiges of the Romanesque church, with its pillars and round arches.[3]

The roof is gabled, with the exception of the side aisles and chapels, which are terraced, and lean-to roofs on the side aisles.[3]

A number of gables are present on the roof at the apse and transept crossing.[57] The bell tower features a baluster and pinnacles.[58] The staircase tower and bell tower feature large windows, giving the sea lookout a panoramic view of the town's surroundings.[58]

The church features some fine gargoyles, including one with a human head dating from the 15th century.[59] A 16th-century gargoyle depicting a monk has been named the "Malaucœureux".[37] Carvings depicting admiration, doubt and boredom have also been recognized.[59]

A sundial adorns the southern facade of the building.

-

Gargoyle.

Gargoyle. -

Gargoyle known as the "Malaucœureux".

Gargoyle known as the "Malaucœureux". -

Marmouset

Marmouset -

Marmouset

Marmouset -

Marmouset

Marmouset

Sacristy and hagioscope[edit]

The apse features a pentagonal building, possibly a sacristy.[3]

It should also be noted the hagioscope[3] or "Trou à lépreux" (leper hole), consisting of an external opening "pierced obliquely through the wall of the south facade",[13] enabling lepers to attend services from the outside.[37] It testifies to the existence of a leper colony in Dives, mentioned in 1475, perhaps located along the cemetery to the south of the church, now ruelle aux Ladres (Ladres Alley),[13] but without a chapel.[60] The Dives leprosarium and its assets were donated to the Pont-l'Évêque hospital in 1696.[61]

Graffitis[edit]

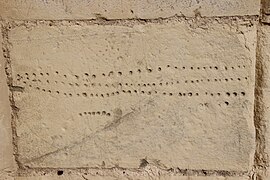

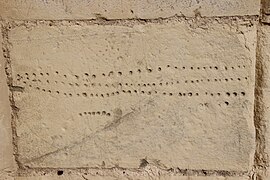

General features[edit]

The building's material, limestone, makes it easy to create graffiti.[50]

The special feature of this religious building is the large number - over 400[29] - of marine graffiti, sculptures of sea monsters and ex-votos of ships, dating from the 15th to the 20th centuries.[29] The graffiti can be dated from the late Middle Ages to the 20th century:[62] while the oldest date from the 15th - 17th centuries, the majority date from the 17th - 18th centuries, and the most recent from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Several graffiti appear to be done by the same hand, and may have been commissioned by a third party.[63] They have been catalogued by Vincent Carpentier, an archaeologist, and published in a book in 2011. Many of the graffiti have a religious character, akin to ex-votos[29] linked to fishing or "an avoided shipwreck".[37]

Graffiti are highly localized:[64] on the exterior, where it is found mainly on the south facade,[37] the bell tower and the southwest tower.[29] The south porch "forms a separate ensemble".[64] Inside, they can be found along the southern wall, not far from the bell tower and on the southwest staircase.[64] The facade and south porch account for half of the corpus, while the bell tower contains around 140.[64] The upper chapel holds seventeen, the nave twelve and the southwest tower seven.[65]

The graffiti are painted "at man's height", except for some that are very high up.[66] The locations of the interior graffiti are hidden, and their presence on the southern wall is perhaps linked to the presence of the cemetery on this side; moreover, this facade did not face the street.[65] The authors may have focused on the "pilgrims' route" in the 19th century.[65] The graffiti is executed in drypoint, lead pencil or sanguine,[50] by "parishioners "[62] who are usually anonymous and adults.[67]

Featured elements[edit]

They depict boats, figures and objects, and are sometimes accompanied by inscriptions.[29] They also feature symbols such as crosses and crucifixes, as well as fleurs-de-lis and rosettes.[68] Incisions known as "devil's claws" are also present.[69] Shoes are depicted, symbolizing a pilgrimage on foot, and can be dated to the 17th and 18th centuries.[52]

Some graffiti depict buildings, perhaps the church.[70] Anthropomorphic representations are very varied: archers, sailors, cartoonish characters. Various animals are also depicted.[70] Inscriptions have been found, but their meaning is not always deciphered.[71] Some names may be boat names or signatures, and some may be children's epitaphs.[72]

A total of two hundred and sixty-eight ship graffiti have been inventoried, with great diversity in the quality of the depictions.[55] Some representations of ships can be dated.[73] Only boats from the "traditional and cultural world of sailing" are represented.[73] Large ships and small vessels, even simple flat-bottomed barges, are present, constituting "a very interesting iconographic record for the successive ages of sailing in the Bay of the Seine":[74] the majority can be dated to the 18th and 19th centuries, but representations range from the late 15th to the early 20th century. The oldest are in the bell tower, at the bottom of the staircase or in the upper chapel.[75] The earliest ships were naves or carrack.[76] Ships from the 17th and 18th centuries are mostly fishing boats, but also larger ones sometimes topped by a fleur-de-lys motif.[77] The south porch features a large number of eighteenth-century boats, while those from the late 18th and 19th centuries include trawlers, brigs and three-masters.[78] Flat-bottomed vessels designed for river navigation are also present, but are difficult to date because their shapes have changed little over the centuries:[79] these vessels are of various types, including écaudes, flètes and gabarres.[80]

-

Graffito with holes.

Graffito with holes. -

Graffito with fleur-de-lis.

Graffito with fleur-de-lis. -

Graffito with fleurs-de-lis on the sail.

Graffito with fleurs-de-lis on the sail. -

Graffito with crucifix.

Graffito with crucifix. -

Graffito with crucifix.

Graffito with crucifix.

Conservation and interpretation issues[edit]

The graffiti are hidden; the act must therefore have been "punishable", even if not devoid of religiosity,[62] they are "an act of individual piety" and not "a gratuitous or recreational act". They are a "collection of offerings motivated by piety".[81]

Graffiti are fragile and unprotected, despite the fact that they are "an authentic heritage of a community which, whether religious or not, still organizes the major events of its social or cultural life around the parish sanctuary".[82] Graffiti are threatened both by wear and tear on the stones due to weathering or pollution[50] and by building restoration campaigns,[83] despite their documentary value,[84] and "(their) high heritage value ".[85] The best-preserved graffiti are located on the upper parts of the exterior walls on the inside of the church.[50]

The proximity of the sea, a "universe of permanent danger", has led to these testimonies, the best-known avatars being the models placed in sailors' chapels.[86] Graffiti display the fears and hopes of seafarers: they are an ex-voto but also bear witness to popular superstition.[81] They are linked to important personal events and are an ex-voto in relation to the community's limited means.[87] The end of this practice corresponds to the great changes that took place in the commune at the end of the 19th century, and to a new stage in religious life, with a "policy of supervising the piety of the working classes".[81] Graffiti had both "a collective and an intimate dimension".[87]

Stained-glass windows[edit]

Medieval stained-glass windows[edit]

The oldest are Les Anges musiciens (The musician Angels), donated by Guy d'Harcourt, Bishop of Lisieux, in the 14th century, according to a fragmentary inscription.[32] Removed during work on the building's glass roof and the installation of new stained-glass windows in the 19th century,[3] the windows became part of the collections of the owner of the Village d'Art Guillaume the Conqueror.

Although it had been classified as an object since 1888, no trace of the stained glass was found until it was rediscovered in 1928.[11] The Le Rémois collection was dispersed in 1973.[3]

It was rediscovered at the end of the 20th century and bought back by the State and the town of Dives. The stained-glass window, which had remained intact during Arcisse de Caumont's lifetime, is only partially preserved.[11] The windows, which were to be restored in 1996, can now be viewed at the Dives-sur-Mer Tourist Office.[3]

There are eight angel musicians in medallions measuring 40 cm (15.7inches) in diameter,[32] out of ten described in the 19th century. The stained glass window was located in the "upper part" of the chevet window.[1] The same window preserved scenes with "the lamb, the pelican, and several scenes of the fall of man" and also "several saints and donors", the middle featuring "a silver key on a gules background with two gold strips",[1] "arms of Guy de Harcourt".[32] The stained glass was made in Rouen or Évreux.[32]

-

General view of the current stained glass window.

General view of the current stained glass window. -

Gittern player.

Gittern player. -

Panpipes player.

Panpipes player. -

Organist.

Organist.

The 19th-century Madonna stained-glass window features medieval medallions: Creation, Temptation of Adam and Eve, Adam and Eve driven from Paradise.[45]

-

Medallion of Creation.

Medallion of Creation. -

Temptation medallion.

Temptation medallion.

Contemporary stained-glass windows[edit]

Stained-glass windows by Louis-Gustave Duhamel-Marette (1836-1900) were installed in the large skylight in 1875.[45] La pêche du Christ and Le Jugement stained glass window were installed in 1880.[88]

- South transept rose window, medallion of the Virgin Mary and Saint Dominic[89]

- Virgin Mary stained glass[90]

- Stained glass window of Saint Peter

- Stained glass window of John the Baptist

- Stained glass window of Saint Dominic receiving the rosary

- Stained glass window of the Death of Saint Joseph

- Vitrail du Christ Saint Sauveur,[89][91] also known as the legend of the miraculous Christ of Dives.

-

Stained-glass window of Saint Peter.

Stained-glass window of Saint Peter. -

Stained-glass window of the Virgin Mary.

Stained-glass window of the Virgin Mary. -

Stained-glass window of St John the Baptist.

Stained-glass window of St John the Baptist. -

Stained-glass window of the Virgin Mary.

-

Stained-glass window.

Furniture[edit]

Works of art[edit]

At the beginning of the 21st century, the building housed the following pieces:

- Saint Anne and Mary

- Adoring angels

- Pietà from 1877

- Polychrome Virgin

- Baptism of Christ, painting by Rémy Eugène Julien dated 1840

south rose window,[37] painting of The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa of Ávila[92][93] by Comte de Dramard.[37]

-

Baptism of Christ, 1840 by Rémy Eugène Julien (1797-1868).

Baptism of Christ, 1840 by Rémy Eugène Julien (1797-1868). -

The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1876), Georges de Dramard (1838-1900).

The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1876), Georges de Dramard (1838-1900). -

Angel worshipper.

Angel worshipper.

In his book, Arcisse de Caumont mentions a "crudely executed" painting depicting the Discovery of the Saint-Sauveur, and inscriptions near the altar.[1] He also mentions tombstones[1] that no longer exist in the building.

List of William the Conqueror's companions[edit]

Above the main entrance door are the names of the 475 principal barons who accompanied William the Bastard to the English coast. This list was placed by the historian and archaeologist Arcisse de Caumont in 1862.[38][88][a] The 24 m2 slab was inaugurated on August 17, 1862.[94][43] Some names are authentic, others not.[38] According to Carpentier, the list drawn up by Léopold Delisle is more authentic than subsequent lists deposited at the Battle Abbey or the Château de Falaise.[43] In particular, he relies on the Domesday Book.[3]

The list refers to the boarding of William the Conqueror's soldiers in the Bay of Dives, an episode recounted in the Bayeux tapestry: 1,000 boats and 8,000 men took part in the operation.[10] In addition to the list in the church, a column was installed in Houlgate[17] and inaugurated on August 18, 1861.[95]

Miscellaneous furniture[edit]

The church preserves an 18th-century lectern.[92] The bird symbolizes good fighting evil incarnated by a serpent, a globe is present.[37] In addition, a southern altarpiece is dedicated to Pentecost.[96]

At the beginning of the 21st century, the building still had three bells, dated 1772 (Marie-Jeanne), 1853 (Marie) and 1891 (Marie-Georgina).[97] Arcisse de Caumont mentions four bells, one of which came from Trousseauville, two from 1772, including Marie-Jeanne, and one dated 1676.[1]

Notes[edit]

- ^ According to Malte-Brun, the list was reproduced from a marble table on which the names were engraved.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m de Caumont, Arcisse (1862). tatistique monumentale du Calvados, t. 4: Arrondissement de Pont-l'Évêque (in French). Caen. pp. 5–14.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "Église Notre-Dame". plateforme ouverte du patrimoine, base Mérimée (in French).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "The church on the website patrimoine-religieux.fr". L'Observatoire du Patrimoine Religieux (in French). Archived from the original on 2023-03-07. Retrieved 2023-12-08.

- ^ a b Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 25. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 46. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b Françoise Dutour and Monique Hauguemar (1991). Dives et les Divais (in French). Condé-sur-Noireau: Éditions Charles Corlet. p. 21. ISBN 2-85480-274-8.

- ^ a b c Association de sauvegarde de l'église Notre-Dame de Dives-sur-Mer (2015). Église Notre-Dame Dives-sur-Mer (in French). p. 3.

- ^ Association de sauvegarde de l'église Notre-Dame de Dives-sur-Mer (2015). Église Notre-Dame Dives-sur-Mer (in French). p. 18.

- ^ a b c Françoise Dutour and Monique Hauguemar (1991). Dives et les Divais (in French). Condé-sur-Noireau: Éditions Charles Corlet. p. 22. ISBN 2-85480-274-8.

- ^ a b c d e Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 38. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b c Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 48. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b Association de sauvegarde de l'église Notre-Dame de Dives-sur-Mer (2015). Église Notre-Dame Dives-sur-Mer (in French). p. 8.

- ^ a b c Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 31. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b Françoise Dutour and Monique Hauguemar (1991). Dives et les Divais (in French). Condé-sur-Noireau: Éditions Charles Corlet. p. 23. ISBN 2-85480-274-8.

- ^ a b Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b c Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. pp. 28–29. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 30. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Françoise Dutour and Monique Hauguemar (1991). Dives et les Divais (in French). Condé-sur-Noireau: Éditions Charles Corlet. p. 24. ISBN 2-85480-274-8.

- ^ a b c d e Françoise Dutour and Monique Hauguemar (1991). Dives et les Divais (in French). Condé-sur-Noireau: Éditions Charles Corlet. p. 25. ISBN 2-85480-274-8.

- ^ Association de sauvegarde de l'église Notre-Dame de Dives-sur-Mer (2015). Église Notre-Dame Dives-sur-Mer (in French). p. 19.

- ^ Françoise Dutour and Monique Hauguemar (1991). Dives et les Divais (in French). Condé-sur-Noireau: Éditions Charles Corlet. p. 109. ISBN 2-85480-274-8.

- ^ a b c Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 49. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 33. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 35. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 6. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b c d Association de sauvegarde de l'église Notre-Dame de Dives-sur-Mer (2015). Église Notre-Dame Dives-sur-Mer (in French). p. 9.

- ^ a b Association de sauvegarde de l'église Notre-Dame de Dives-sur-Mer (2015). Église Notre-Dame Dives-sur-Mer (in French). p. 20.

- ^ a b c d e f g Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 39. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 40. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b c Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 42. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 41. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b c d Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 52. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Françoise Dutour and Monique Hauguemar (1991). Dives et les Divais (in French). Condé-sur-Noireau: Éditions Charles Corlet. p. 108. ISBN 2-85480-274-8.

- ^ a b c d Françoise Dutour and Monique Hauguemar (1991). Dives et les Divais (in French). Condé-sur-Noireau: Éditions Charles Corlet. p. 107. ISBN 2-85480-274-8.

- ^ Françoise Dutour and Monique Hauguemar (1991). Dives et les Divais (in French). Condé-sur-Noireau: Éditions Charles Corlet. p. 27. ISBN 2-85480-274-8.

- ^ Association de sauvegarde de l'église Notre-Dame de Dives-sur-Mer (2015). Église Notre-Dame Dives-sur-Mer (in French). p. 21.

- ^ a b c d Françoise Dutour and Monique Hauguemar (1991). Dives et les Divais (in French). Condé-sur-Noireau: Éditions Charles Corlet. p. 34. ISBN 2-85480-274-8.

- ^ a b Françoise Dutour and Monique Hauguemar (1991). Dives et les Divais (in French). Condé-sur-Noireau: Éditions Charles Corlet. p. 35. ISBN 2-85480-274-8.

- ^ a b c d e Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 68. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Françoise Dutour and Monique Hauguemar (1991). Dives et les Divais (in French). Condé-sur-Noireau: Éditions Charles Corlet. pp. 52–53. ISBN 2-85480-274-8.

- ^ a b c Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 69. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Actu. "L'imposant chantier de réfection des vitraux de l'église de Dives-sur-Mer". On actu.fr (in French).

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 47. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 5. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ "Eglise Dives-Houlgate : Présentation". www.ndml.fr.

- ^ a b c d e Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 79. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b c Françoise Dutour and Monique Hauguemar (1991). Dives et les Divais (in French). Condé-sur-Noireau: Éditions Charles Corlet. pp. 108–109. ISBN 2-85480-274-8.

- ^ a b Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 91. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 43. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 44. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 100. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 45. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 51. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b Association de sauvegarde de l'église Notre-Dame de Dives-sur-Mer. Église Notre-Dame Dives-sur-Mer (in French). p. 16.

- ^ Association de sauvegarde de l'église Notre-Dame de Dives-sur-Mer (2015). Église Notre-Dame Dives-sur-Mer (in French). pp. 6–7.

- ^ Association de sauvegarde de l'église Notre-Dame de Dives-sur-Mer (2015). Église Notre-Dame Dives-sur-Mer (in French). p. 7.

- ^ a b c Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 83. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 85. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b c d Vincent, Carpentier (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 81. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b c Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 82. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 80. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. pp. 129–130. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. pp. 86–88. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 92. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. pp. 93–96. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 84. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 101. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 108. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. pp. 113–114. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. pp. 121–122. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. pp. 122–128. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b c Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 130. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 21. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carptentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 131. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. p. 131. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- ^ a b Association de sauvegarde de l'église Notre-Dame de Dives-sur-Mer (2015). Église Notre-Dame Dives-sur-Mer (in French). p. 10.

- ^ a b Association de sauvegarde de l'église Notre-Dame de Dives-sur-Mer (2015). Église Notre-Dame Dives-sur-Mer (in French). p. 11.

- ^ Ministère de la culture. "verrière figurée : Vie de la Vierge, Médaillons de la Genèse". fr.

- ^ "ensemble de 8 verrières". Ministère de la culture (in French).

- ^ a b Association de sauvegarde de l'église Notre-Dame de Dives-sur-Mer (2015). Église Notre-Dame Dives-sur-Mer (in French). p. 13.

- ^ "tableau et son cadre : Sainte Thérèse d'Avila". Ministère de Culture (in French).

- ^ Association de sauvegarde de l'église Notre-Dame de Dives-sur-Mer (2015). Église Notre-Dame Dives-sur-Mer (in French). p. 14.

- ^ Françoise Dutour and Monique Hauguemar (1991). Dives et les Divais (in French). Condé-sur-Noireau: Éditions Charles Corlet. p. 55. ISBN 2-85480-274-8.

- ^ "autel latéral sud, retable et tableau : Pentecôt". Ministère de Culture (in French).

- ^ Association de sauvegarde de l'église Notre-Dame de Dives-sur-Mer (2015). Église Notre-Dame Dives-sur-Mer (in French). p. 22.

See also[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

- de Caumont, Arcisse (1862). Statistique monumentale du Calvados: Arrondissement de Pont-l'Évêque (in French). Vol. 4. Caen: Hardel. pp. 5–14.

- Carpentier, Vincent (2011). L'église de Dives et ses graffiti marins (in French). Caen: Éditions Cahiers du temps. ISBN 978-2-35507-039-6.

- Dutour, Françoise; Hauguemar, Monique (1991). Dives et les Divais (in French). Condé-sur-Noireau: Éditions Charles Corlet. p. 125. ISBN 2-85480-274-8.

- Salet, Francis (1987). "Vitraux de Dives-sur-Mer". Bulletin Monumental (in French). 145 (1): 124.

- Association de sauvegarde de l'église Notre-Dame de Dives-sur-Mer (2015). Église Notre-Dame Dives-sur-Mer, Dives-sur-Mer.

- Le patrimoine des communes du Calvados (in French). Vol. 14. Flohic Éditions. 2001. p. 1715. ISBN 978-2-84234-111-4.

External links[edit]

- Religious resources: Clochers de France · GCatholic.org

- Architectural resources: Mérimée · Structurae

- "Site officiel de la paroisse". ndml.fr (in French). Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- "L'église sur le site de la commune". dives-sur-mer.fr (in French). Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- "Les travaux de l'église Notre-Dame possibles grâce au diocèse". ouest-france.fr (in French). April 11, 2013. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- "La restauration des transepts bientôt financée". ouest-france.fr (in French). September 29, 2013. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- "L'imposant chantier de réfection des vitraux de l'église de Dives-sur-mer". actu.fr. June 29, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- Video on YouTube