Claude Cahun

Claude Cahun | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Lucy Renee Mathilde Schwob October 25, 1894 Nantes, France |

| Died | December 8, 1954 (aged 60) |

| Resting place | St Brelade's Church 49°11′03″N 2°12′10″W / 49.1841°N 2.2029°W |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Photography, writing, sculpture, collage |

| Movement | Surrealism |

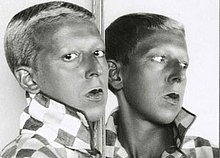

Claude Cahun (25 October 1894 – 8 December 1954) was a French artist, photographer and writer.[1] Her work was both political and personal, and often undermined traditional concepts of gender roles.

Though Cahun's writings suggested she identified as agender, most academic writings use feminine pronouns when discussing her and her work, as there is little documentation that gender neutral pronouns were used or preferred by the artist. In 1929 Cahun translated Havelock Ellis' theories on the third gender.

Early life

Born in Nantes as Lucy Renee Mathilde Schwob, Cahun was the niece of an avant-garde writer Marcel Schwob and the great-niece of Orientalist David Léon Cahun. When Cahun was four years old, her mother, Mary-Antoinette Courbebaisse, began suffering from mental illness, which ultimately led to her permanent internment at a psychiatric facility.[2] Due to the absence of her mother, Cahun was brought up by her grandmother, Mathilde Cahun.

Cahun attended a private high school in Surrey after experiences with anti-Semetism at her high school in Nantes.[3] She attended the University of Paris, Sorbonne.[3]

She began making photographic self-portraits as early as 1912 (aged 18), and continued taking images of herself through the 1930s.

Around 1919, she changed her name to Claude Cahun, after having previously used the names Claude Courlis (after the curlew) and Daniel Douglas (after Lord Alfred Douglas). During the early 20s, she settled in Paris with her lifelong partner and step-sibling Suzanne Malherbe. For the rest of their lives together, Cahun and Malherbe (who adopted the name "Marcel Moore") collaborated on various written works, sculptures, photomontages and collages. The two published articles and novels, notably in the periodical "Mercure de France", and befriended Henri Michaux, Pierre Morhange and Robert Desnos.

Around 1922 Claude and Malherbe began holding artists' salons at their home. Among the regulars who would attend were artists Henri Michaux and André Breton and literary entrepreneurs Sylvia Beach and Adrienne Monnier.[4]

Work

Cahun's work encompassed writing, photography, and theater. She is most remembered for her highly staged self-portraits and tableaux that incorporated the visual aesthetics of Surrealism.

Her published writings include "Heroines," (1925) a series of monologues based upon female fairy tale characters and intertwining them with witty comparisons to the contemporary image of women; Aveux non-avenus, (Carrefour, 1930) a book of essays and recorded dreams illustrated with photomontages; and several essays in magazines and journals.[5]

In 1932 she joined the Association des Écrivains et Artistes Révolutionnaires, where she met André Breton and René Crevel. Following this, she started associating with the surrealist group, and later participated in a number of surrealist exhibitions, including the London International Surrealist Exhibition (New Burlington Gallery) and Exposition surréaliste d'Objets (Charles Ratton Gallery, Paris), both in 1936. In 1934, she published a short polemic essay, Les Paris sont Ouverts, and in 1935 took part in the founding of the left-wing group Contre Attaque, alongside André Breton and Georges Bataille.

In 1994 the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London held an exhibition of Cahun's photographic self-portraits from 1927–47, alongside the work of two young contemporary British artists, Virginia Nimarkoh and Tacita Dean, entitled Mise en Scene. In the surrealist self-portraits, Cahun represented herself as a dandy, skinhead and androgyne, nymph, model and soldier.[6]

In 2007, David Bowie created a multi-media exhibition of Cahun’s work in the gardens of the General Theological Seminary in New York. It was part of a venue called the Highline Festival, which also included offerings by Air, Laurie Anderson, Mike Garson and Ricky Gervais. Bowie on Cahun:

You could call her transgressive or you could call her a cross dressing Man Ray with surrealist tendencies. I find this work really quite mad, in the nicest way.Outside of France and now the UK she has not had the kind of recognition that, as a founding follower, friend and worker of the original surrealist movement, she surely deserves. Meret Oppenheim was not the only one with a short haircut.

Nothing could better do this, I thought, than to show her photographs through the digital technology of the 21st century and in a setting that embraces the pastoral sanctuary of her last years.[7]

World War II activism

In 1937 Cahun and Malherbe settled in Jersey. Following the fall of France and the German occupation of Jersey and the other Channel Islands, they became active as resistance workers and propagandists. Fervently against war, the two worked extensively in producing anti-German fliers. Many were snippets from English-to-German translations of BBC reports on the Nazis' crimes and insolence, which were pasted together to create rhythmic poems and harsh criticism. The couple then dressed up and attended many German military events in Jersey, strategically placing them in soldier's pockets, on their chairs, etc. Also, they inconspicuously crumpled up and threw their fliers into cars and windows. In many ways, Cahun and Malherbe's resistance efforts were not only political but artistic actions, using their creative talents to manipulate and undermine the authority which they despised. In many ways, Cahun's life's work was focused on undermining a certain authority, however her specific resistance fighting targeted a physically dangerous threat. In 1944 she was arrested and sentenced to death, but the sentences were never carried out. However, Cahun's health never recovered from her treatment in jail, and she died in 1954. She is buried in St Brelade's Church with her partner Suzanne Malherbe.

Social critique and legacy

Cahun worked for herself and did not want to be famous.[8] It wasn't until 40 years after her death that Cahun's work became recognized, mostly thanks to François Leperlier In many ways, Cahun's life was marked by a sense of role reversal, and her public identity became a commentary upon the public's notions of sexuality, gender, beauty, and logic. Her adoption of a sexually ambiguous name, and her androgynous self-portraits display a revolutionary way of thinking and creating, experimenting with her audience's understanding of photography as a documentation of reality. their poetry challenged gender roles and attacked the increasingly modern world's social and economic boundaries. Also, Cahun's participation in the Parisian Surrealist movement diversified the group's artwork and ushered in new representations. Where most Surrealist artists were men, and their primary images were of women as isolated symbols of eroticism, Cahun epitomized the chameleonic and multiple possibilities of genders and of the body. Her photographs, writings, and general life as an artistic and political revolutionary continue to influence countless artists, namely Cindy Sherman, Nan Goldin and Del LaGrace Volcano.

Cahun's collected writings were published in 2002 as Claude Cahun – Écrits (ISBN 2-85893-616-1), edited by Françoise Leperlier.

Bibliography (French language)

- Vues et Visions (Pseudonym Claude Courlis), Mercure de France, No. 406, 16 May 1914

- La 'Salomé' d'Oscar Wilde. Le procés Billing et les 47000 pervertis du Livre noir, Mercure de France, No. 481, 1 July 1918

- Le poteau frontière (Pseudonym Daniel Douglas), La Gerbe, No. 3, December 1918

- Au plus beau des anges (Pseudonym Daniel Douglas), La Gerbe, No. 3, December 1918

- Cigarettes (Pseudonym Daniel Douglas), La Gerbe, No. 3, December 1918

- Aux Amis des livres, La Gerbe, No. 5, February 1919

- La Sorbonne en robe de fête (Pseudonym Daniel Douglas), La Gerbe, No. 5, February 1919

- La possession du Monde, par Georges Duhamel, La Gerbe, No. 7, April 1919

- Les Gerbes (Pseudonym Daniel Douglas), La Gerbe, No. 7, April 1919

- L'amour aveugle (Pseudonym Daniel Douglas), La Gerbe, No. 12, September 1919

- La machine magique (Pseudonym Daniel Douglas), La Gerbe, No. 12, September 1919

- Mathilde Alanic. Les roses refleurissent, Le Phare de la Loire, 29 June 1919

- Le théâtre de mademoiselle, par Mathias Morhardt, Le Phare de la Loire, 20 July 1919

- Vues et Visions, with Illustrations by Marcel Moore, Paris: Georges Crès & Cie, 1919

- Paraboles (Pseudonym Daniel Douglas), La Gerbe, No. 17, February 1920

- Une conférence de Georges Duhamel (Pseudonym Daniel Douglas), La Gerbe, No. 19, April 1920

- Marcel Schwob, La Gerbe, No. 20, May 1920

- Boxe (Pseudonym Daniel Douglas), La Gerbe, No. 22, July 1920

- Old Scotch Whisky, La Gerbe, No. 27, December 1920

- A propos d'une conference and Méditations à la faveur d'un Jazz Band, La Gerbe, No. 27, December 1920

- Héroïnes: 'Eve la trop crédule', 'Dalila, femme entre les femmes', 'La Sadique Judith', 'Hélène la rebelle', 'Sapho l'incomprise', 'Marguerite, sœur incestueuse', 'Salomé la sceptique', Mercure de France, No. 639, 1 February 1925

- Héroïnes: 'Sophie la symboliste', 'la Belle', Le Journal littéraire, No. 45, 28 February 1925

- Méditation de Mademoiselle Lucie Schwob, Philosophies, No. 5/6, March 1925

- Récits de rêve, in the special edition Les rêves, Le Disque vert, Third year, Book 4, No. 2, 1925

- Carnaval en chambre, La Ligne de cœur, Book 4, March 1926

- Ephémérides, Mercure de France, No. 685, 1 January 1927

- Au Diable, Le Plateau, No. 2, May–June 1929

- Ellis, Havelock: La Femme dans la société – I. L'Hygiene sociale, translated by Lucy Schwob, Mercure de France, 1929

- Aveux non avenus, illustrated by Marcel Moore, Paris: Editions du Carrefour, 30 May 1930

- Review on Bibliothèque Nationale Gallica

- Frontière Humaine, self-portrait, Bifur, No. 5, April 1930

- Protestez (AEAR), Feuille rouge, No. 2, March 1933

- Contre le fascisme Mays aussi contre l'impérialisme francais (AEAR), Feuille rouge, No. 4, May 1933

- Les Paris sont ouvert, Paris: José Corti, May 1934

- Union de lutte des intellectuels révolutionnaires, Contre-Attaque, 7 October 1935

- Prenez garde aux objets domestique, Cahier d'Art I-II, 1936

- Sous le feu des canons francais ... et alliés, Contre-Attaque, March 1936

- Dissolution de Contre-Attaque, L'Œuvre, 24 March 1936

- Exposition surréaliste d'objets, Exhibition at the Charles Ratton Gallery, Paris, 22–29 May 1936. Items listed by Claude Cahun are Un air de famille and Souris valseuses

- Il n'y a pas de liberté pour les ennemis de la liberté, 20 July 1936

- Deharme, Lise: Le Cœur de Pic, 32 illustrated with 20 photos by Claude Cahun, Paris: José Cortis, 1937

- Adhésion à la Fédération Internationale de l'Art Révolutionnaire Indépendant, Clé, No. 1, January 1939

- À bas les lettres de cachets! À bas la terreur grise! (FIARI), June 1939

Bibliography (English language)

- Weaver, M. and Hammond, A. "Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore: Surrealist Sisters." History of Photography, Summer 1993, 17 (2), 217.

- Laurie J. Monahan, "Radical Transformations: Claude Cahun and the Masquerade of Womanliness". In: Catherine de Zegher (ed.), Inside the Visible, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston & MIT Press, 1996.

- Claude Cahun, Tacinta Dean and Virginia Nimarkoh: Mise-En-Scene: Institute for Contemporary Arts: London: 1996: ISBN 0-905263-59-6

- Shelley Rice:Inverted Odysseys: Claude Cahun, Maya Deren and Cindy Sherman: Cambridge: Massachuesetts: MIT Press: 1999: ISBN 0-262-68106-4

- Tirza True Latimer, "Narcissus and Narcissus: Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore," in Women Together/Women Apart: Portraits of Lesbian Paris. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-8135-3595-6

- 'Playing a Part: The Story of Claude Cahun,' drama documentary film by Lizzie Thynne, Brighton: Sussex University, 2004. Available from l.thynne@sussex.ac.uk.

- Louise Downie: Don't Kiss Me: The Art of Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore: London: Aperture: 2006: ISBN 1-85437-679-9

- Julie Cole: "Claude Cahun, Marcel Moore and the Collaborative Construction of a Lesbian Subjectivity." In: Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard (eds.), Reclaiming Female Agency: Feminist Art History after Postmodernism, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2005.

- Marcus Williamson: "Claude Cahun at School in England", Lulu, 2011. ISBN 978-1-257-63952-6

- Jennifer L. Shaw: Reading Claude Cahun's Disavowals, Ashgate, 2013.

- Jennifer L. Shaw, “From Cabanel to Claude Cahun: More Manifestations of Venus” in Venus as Muse: Figurations of the Creative ed. Sebastian Goth, Rodopi, 2015.

- Jennifer L. Shaw, “Neonarcissism” in *Nierika* (Mexico City: Universidad Iberoamericana), "La Política Visual del Narcisismo: estudios de casos," Vol. 2, no. 2, May 31, 2013, 19-26.

- Jennifer L. Shaw, “Deconstructing Girlhood: Claude Cahun’s ‘Sophie la Symboliste,’ in Working Girls: Women’s Cultural Production During the Interwar Years, ed. Paula Birnbaum and Edwin Mellen Press, 2009.

- Jennifer L. Shaw, “Narcissus and the Magic Mirror” in Don’t Kiss Me: The Art of Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore, ed. Louise Downie, Tate Publishing, 2006.

- Colvile, Georgiana M.M. "Self-Representation as Symptom: The Case of Claude Cahun." Interfaces: Women, Autobiography, Image, Performance. The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 2005. p. 263-288.

Film

- Playing a Part, by Lizzie Thynne

- Lover Other, by Barbara Hammer

- Magic Mirror, by Sarah Pucill

Theater

- Claude, by Andrea Kleine

Exhibitions

- International Surrealist Exhibition, London – June–July 1936

- Surrealist Sisters Jersey Museum 1993

- Mise en Scene – Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), London – 13 October to 27 November 1994

- Claude Cahun : photographe : Claude Cahun 1894–1954 – Musée d'Art Moderne, Paris – 23 June to 17 September 1995

- Neue Museum, Graz, Austria – 4 October to 3 December 1997

- Fotografische Sammlung, Museum Folkwang Essen, Germany – 18 January – 8 March 1998

- Don't Kiss Me – Disruptions of the Self in the Work of Claude Cahun – Presentation House Gallery, North Vancouver, Canada – 7 November to 20 December 1998

- Don't Kiss Me – Disruptions of the Self in the Work of Claude Cahun – Art Gallery of Ontario, Ontario, Canada – 8 May to 18 July 1999

- Inverted Odysseys – Grey Art Gallery, New York City – 16 November 1999 to 29 January 2000

- Surrealism: Desire Unbound – Tate Modern, London – 20 September 2001 to 1 January 2002

- Claude Cahun – Retrospective – IVAM, Valencia, Spain – 8 November 2001 to 20 January 2002

- I am in training – don't kiss me – New York City – May 2004

- Acting Out: Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore – The Judah L. Magnes Museum – 4 April – July 2005

- Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, ME, USA – September to October 2005

- Jersey Museum – November 2005 to January 2006

- Cahun Exhibition – Jeu de Paume, Place de la Concorde, Paris – 24 May to 25 September 2011.

- Cahun Exhibition – Will also tour to Art Institute of Chicago and La Virreina Centre de la image, Barcelona in 2011/2012.

- March 2012 in Cahun's home town of Nantes, as part of two seasons on 'Le film et l'acte de création: Entre documentaire et oeuvre d'art' ('Film and the creative act: Between documentary and the work of art').

References

- ^ "Claude Cahun – Chronology". Retrieved 18 October 2007.

- ^ Colvile, Georgiana M.M. (2005). "Self-Representation as Symposium: The Case of Claude Cahun". Interfaces: Women, Autobiography, Image, Performance: 265. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ a b Doy, Gen (2007). Claude Cahun: A Sensual Politics of Photography. London/New York: I.B. Tauris. pp. xv–xvi. ISBN 9781845115517.

- ^ Schirmer, Lothar (2001). Women Seeing Women, A Pictorial History of Women's Photography. NY: Norton. p. 208.

- ^ Penelope Rosemont, Surrealist Women 1998, University of Texas Press

- ^ Katy Deepwell ' Uncanny Resemblances: Restaging Claude Cahun in 'Mise en Scene issue 1 Dec 1996 n.paradoxa: international feminist art journal online pp. 46–51

- ^ "David Bowie on DavidBowie.com". Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- ^ Colvile, Georgiana M.M. (2005). "Self-Representation as Symposium: The Case of Claude Cahun". Interfaces: Women, Autobiography, Image, Performance: 263–288.

Sources

- Claude Cahun info page

- Claude Cahun tribute and biography page

- The Daily Beast, 2015-04-21, "Claude Cahun: The Lesbian Surrealist Who Defied the Nazis"

- Feminist Art Archive, University of Washington, 2012, "Claude Cahun"

- Bower, Gavin James. “Claude Cahun: Finding a Lost Great.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 14 Feb. 2012. Web. 11 Dec. 2012

- Elkin, Lauren. “Reading Claude Cahun.” Quarterly Conversation RSS. Quarterly Conversation RSS, n.d. Web. 11 Dec. 2012

- Gen, Doy. “META: Claude Cahun-A Sensual Politics of Photography.” META-Magazine.com. MEGA, n.d. Web. 11 Dec. 201

- Guerilla Girls, The. “The 20th Century: Women of Isms.” The Guerrilla Girls’ Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art. New York: Penguin Group, 1998. 62-63. Print

- Zachmann, Gayle. The Photographic Intertext: Invisible Adventures in the Work of Claude Cahun. 3rd ed. Vol. 10. N.p.: Taylor and Francis Group, 2006. CrossRef. Web. 11 Dec. 2012.

External links

Media related to Claude Cahun at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Claude Cahun at Wikimedia Commons- Claude Cahun Home Page

- Claude Cahun, "Je est une autre" in PURPOSE #7 (photographic webmag)

- De l'Éros des femmes surréalistes et de Claude Cahun en particulier by Georgina M.M. Colvile

- Prof. Gen Doy on Claude Cahun

- Claude Cahun in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website

- 1894 births

- 1954 deaths

- Women Surrealists

- People from Nantes

- French Jews

- French photographers

- Lesbian artists

- Lesbian writers

- Transgender and transsexual writers

- Genderqueer people

- Surrealist artists

- French women artists

- Women photographers

- Feminist artists

- LGBT writers from France

- LGBT Jews

- People from Saint Saviour, Jersey

- French women writers

- French artists

- 20th-century women artists