Comics Code Authority

The Comics Code Authority (CCA) is an organization established to regulate the content of comic books in the United States. Member publishers submit comic books to the CCA, which screens them for conformance to its Comic Code, and authorizes the use of their seal on the cover if the books comply. At the height of its influence, it was a de facto censor for the U.S. comic book industry.

Founding

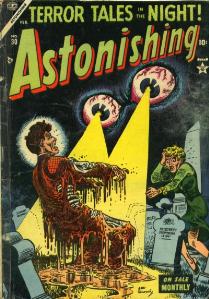

The CCA was founded in 1954, in response to public concern about what was deemed inappropriate material in many comic books. This included graphic depictions of violence or gore in crime and horror comics, as well as the sexual innuendo of what aficionados refer to as good girl art. Dr. Fredric Wertham's book Seduction of the Innocent rallied opposition to this type of material in comics, arguing that it was harmful to the children who made up a large segment of the comic book audience. Senate subcommittee hearings led by Estes Kefauver had many publishers concerned about government regulation, prompting them to form a self-regulatory body instead.

In its original form, the Code prohibited depictions of gore, sexuality, and excessive violence; required that authority figures were never to be ridiculed or presented disrespectfully, and that good must always win; and prohibited scenes with vampires, werewolves, ghouls or zombies. The code also prohibited advertisements of liquor, tobacco, knives, fireworks, nude pin-ups and postcards, and "toiletry products of questionable nature".

There were critics from both sides of the debate. Wertham dismissed the Code as an inadequate half-measure. William Gaines, head of EC Comics — whose best-selling titles included Crime SuspenStories, The Vault of Horror and The Crypt of Terror — complained about clauses prohibiting titles with the words "Terror", "Horror", or "Crime", as well as the clause banning vampires, werewolves, and zombies. Indeed, these restrictions quickly made EC unprofitable, and all its comics besides MAD were dropped within brief years following the CCA's introduction.

While the CCA did not have any legal authority over other publishers, magazine distributors often refused to carry comics without the CCA's seal of approval. Some publishers thrived under these restrictions, others adapted by canceling unapproved publications and focusing on Code-approved content, and others were unable to survive. The range of comics published contracted substantially following the introduction of the Code. Older readers abandoned the medium, dissatisfied by stories written within parameters intended to make them suitable for children. The medium came to be even more strongly associated with children, a perception that persists to this day.

Updating

In the late 1960s, the underground comics scene arose, with artists creating comics that delved into subject matter explicitly not allowed by the Code. However, these comics were distributed largely through other channels, such as head shops, making CCA approval unnecessary for their success.

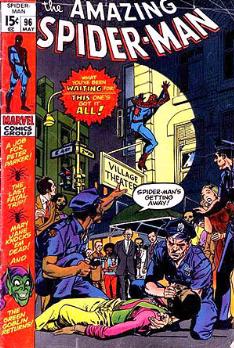

In 1971, Marvel Comics editor-in-chief Stan Lee was approached by the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare to do a comic book story about drug abuse. Lee agreed and wrote a three-part Spider-Man story portraying drug use as dangerous and unglamorous. The CCA refused to approve the story because of the presence of narcotics, deeming the context of the story irrelevant. Lee, with the approval of his boss, Martin Goodman, published the story regardless in The Amazing Spider-Man #96-98 (May-July 1971), without CCA approval. The storyline was well-received and the CCA's argument for denying its approval was criticized as counterproductive.

"That was the only big issue that we had" with the Code, Lee recalled in a 1998 interview.

- "I could understand them; they were like lawyers, people who take things literally and technically. The Code mentioned that you mustn't mention drugs and, according to their rules, they were right. So I didn't even get mad at them then. I said, 'Screw it' and just took the Code seal off for those three issues. Then we went back to the Code again. I never thought about the Code when I was writing a story, because basically I never wanted to do anything that was to my mind too violent or too sexy. I was aware that young people were reading these books, and had there not been a Code, I don't think that I would have done the stories any differently". [1]

The Code subsequently was revised in 1971 to permit the depiction of "narcotics or drug addiction" if presented "as a vicious habit". Also newly allowed were vampires, ghouls, and werewolves, "when handled in the classic tradition of Frankenstein, Dracula, and other high caliber literary works written by Edgar Allan Poe, Saki, Conan Doyle and other respected authors whose works are read in schools around the world." Zombies, lacking a respected "literary" background, remained forbidden. However, Marvel skirted the zombie restriction in the mid-1970s by calling the apparently deceased, mind-controlled followers of various Haitian super-villains "zuvembies".

Despite periodic revisions to the Code to reflect changing attitudes about appropriate subject matter (e.g. the original ban on making reference to homosexuality as a sexual perversion was revised in 1989 to include gay and lesbians among the classes of people that comic books could not stereotype) its influence on the medium continued to diminish, and publishers gradually reduced the prominence of the seal on their covers. The development of new distribution channels, especially "direct market" comics specialty shops, provided additional means for non-Code books to reach a large audience, and newsstand distribution — a shrinking component of industry sales — became less important.

A new generation of publishers emerged in the 1980s and 1990s that distributed solely to specialty shops and did not join the CCA or submit their books for approval. DC Comics, Marvel, and other CCA sponsors began to publish lines of comics intended for adult audiences, without the CCA seal. For example, in the 1990s DC Comics' Milestone imprint submitted its books to the CCA, but published them regardless of the CCA's ruling, placing the seal only on issues that passed. In 2001, Marvel Comics withdrew from the CCA in favor of its own ratings system. As of 2005, DC Comics and Archie Comics are the only major publishers still submitting their books for CCA approval, and in the case of DC, only books from their Johnny DC and DC Universe superhero lines are submitted.

1954 Code highlights

- Crimes shall never be presented in such a way as to create sympathy for the criminal, to promote distrust of the forces of law and justice, or to inspire others with a desire to imitate criminals.

- If crime is depicted it shall be as a sordid and unpleasant activity.

- Criminals shall not be presented so as to be rendered glamorous or to occupy a position which creates a desire for emulation.

- In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.

- Scenes of excessive violence shall be prohibited. Scenes of brutal torture, excessive and unnecessary knife and gunplay, physical agony, gory and gruesome crime shall be eliminated.

- No comic magazine shall use the word horror or terror in its title.

- All scenes of horror, excessive bloodshed, gory or gruesome crimes, depravity, lust, sadism, masochism shall not be permitted.

- All lurid, unsavory, gruesome illustrations shall be eliminated.

- Inclusion of stories dealing with evil shall be used or shall be published only where the intent is to illustrate a moral issue and in no case shall evil be presented alluringly, nor so as to injure the sensibilities of the reader.

- Scenes dealing with, or instruments associated with walking dead, torture, vampires and vampirism, ghouls, cannibalism, and werewolfism are prohibited.

- Profanity, obscenity, smut, vulgarity, or words or symbols which have acquired undesirable meanings are forbidden.

- Nudity in any form is prohibited, as is indecent or undue exposure.

- Suggestive and salacious illustration or suggestive posture is unacceptable.

- Females shall be drawn realistically without exaggeration of any physical qualities.

- Illicit sex relations are neither to be hinted at nor portrayed. Violent love scenes as well as sexual abnormalities are unacceptable.

- Seduction and rape shall never be shown or suggested.

- Sex perversion or any inference to same is strictly forbidden.

- Nudity with meretricious purpose and salacious postures shall not be permitted in the advertising of any product; clothed figures shall never be presented in such a way as to be offensive or contrary to good taste or morals.

See also

Reference

- Dean, M. (2001) Marvel drops Comics Code, changes book distributor. The Comics Journal 234, p.19.