Conjugated system

In chemistry, a conjugated system is a system of connected p-orbitals with delocalized electrons in molecules with alternating single and multiple bonds, which in general may lower the overall energy of the molecule and increase stability. Lone pairs, radicals or carbenium ions may be part of the system. The compound may be cyclic, acyclic, linear or mixed.

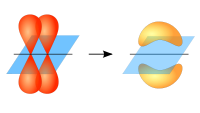

Conjugation is the overlap of one p-orbital with another across an intervening sigma bond (in transition metals d-orbitals can be involved).[1]

A conjugated system has a region of overlapping p-orbitals, bridging the adjacent single bonds. They allow a delocalization of pi electrons across all the adjacent aligned p-orbitals.[2] The pi electrons do not belong to a single bond or atom, but rather to a group of atoms.

The largest conjugated systems are found in graphene, graphite, conductive polymers, and carbon nanotubes.

Mechanism

Conjugation is possible by means of alternating single and double bonds. As long as each contiguous atom in a chain has an available p-orbital, the system can be considered conjugated. For example, furan (see picture) is a five-membered ring with two alternating double bonds and an oxygen in position 1. Oxygen has two lone pairs, one of which occupies a p-orbital on that position, thereby maintaining the conjugation of that five-membered ring. The presence of a nitrogen in the ring or groups α to the ring like a carbonyl group (C=O), an imine group (C=N), a vinyl group (C=C), or an anion will also suffice as a source of pi orbitals to maintain conjugation.

There are also other types of conjugation. Homoconjugation[3] is an overlap of two π-systems separated by a non-conjugating group, such as CH2. For example, the molecule CH2=CH–CH2–CH=CH2 (1,4-pentadiene) is homoconjugated because the two C=C double bonds (which are π-systems because each double bond contains one π bond) are separated by one CH2 group.[4]

Conjugated cyclic compounds

Cyclic compounds can be partly or completely conjugated. Annulenes, completely conjugated monocyclic hydrocarbons, may be aromatic, non-aromatic or anti-aromatic.

Aromatic compounds

Conjugated, planar, cyclic compounds that follow Hückel's rule are aromatic and exhibit an unusual stability. The classic example benzene has a system of 6 π-electrons, which forms the benzene ring along the planar σ-ring with its 12 electrons. For benzene there are two equivalent conjugated Lewis structures, so that the true molecular state is a quantum-mechanical combination of the two structures with six equivalent CC bonds which are intermediate between single and double bonds, and all of equal length and strength.

Non-aromatic compounds

Not all compounds with alternating double and single bonds are aromatic. Cyclooctatetraene, for example, possesses alternating single and double bonds. The molecule typically adopts a "tub" conformation. Because the p-orbitals of the molecule do not align themselves well in this non-planar molecule, the electrons are not as easily shared between the carbon atoms. The molecule can be still considered conjugated, but is neither aromatic, nor antiaromatic (because it is not planar).

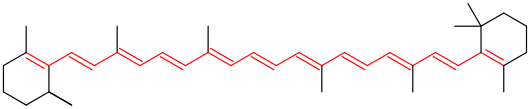

Conjugated systems in pigments

Many pigments make use of conjugated electron systems to absorb visible light, giving rise to strong colors. For example the long conjugated hydrocarbon chain in beta-carotene leads to its strong orange color. When an electron in the system absorbs a photon of light of the right wavelength, it can be promoted to a higher energy level. A simple model of the energy levels is provided by the quantum-mechanical problem of a one-dimensional particle in a box of length L, representing the movement of a pi electron along a long conjugated chain of carbon atoms. In this model the lowest possible absorption energy corresponds to the energy difference between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO). For a chain of n C=C bonds or 2n carbon atoms in the molecular ground state, there are 2n pi electrons occupying n molecular orbitals, so that the energy gap is[5]

Since the box length L is proportional to the number of C=C bonds n, this means that the energy ΔE of a photon absorbed in the HOMO-LUMO transition is approximately proportional to 1/n. The photon wavelength λ = hc/ΔE is then approximately proportional to n. Although this model is very approximate, λ does in general increase with n (or L) for similar molecules. For example the HOMO-LUMO absorption wavelengths for conjugated butadiene, hexatriene and octatetraene are 217 nm, 252 nm and 304 nm respectively.[6]

Many electronic transitions in conjugated π-systems are from a predominantly bonding molecular orbital (MO) to a predominantly antibonding MO (π to π*), but electrons from non-bonding lone pairs can also be promoted to a π-system MO (n to π*) as often happens in charge-transfer complexes. A HOMO to LUMO transition is made by an electron if it is allowed by the selection rules for electromagnetic transitions. Conjugated systems of fewer than eight conjugated double bonds absorb only in the ultraviolet region and are colorless to the human eye. With every double bond added, the system absorbs photons of longer wavelength (and lower energy), and the compound ranges from yellow to red in color. Compounds that are blue or green typically do not rely on conjugated double bonds alone.

This absorption of light in the ultraviolet to visible spectrum can be quantified using ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy, and forms the basis for the entire field of photochemistry.

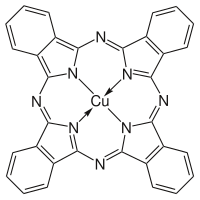

Conjugated systems that are widely used for synthetic pigments and dyes are diazo and azo compounds and phthalocyanine compounds.

Phthalocyanine compounds

Conjugated systems not only have low energy excitations in the visible spectral region but they also accept or donate electrons easily. Phthalocyanines, which, like Phthalo Blue and Phthalo Green, often contain a transition metal ion, exchange an electron with the complexed transition metal ion that easily changes its oxidation state. Pigments and dyes like these are charge-transfer complexes.

Porphyrins and similar compounds

Porphyrins have conjugated molecular ring systems (macrocycles) that appear in many enzymes of biological systems. As a ligand, porphyrin forms numerous complexes with metallic ions like iron in hemoglobin that colors blood red. Hemoglobin transports oxygen to the cells of our bodies. Porphyrin–metal complexes often have strong colors. A similar molecular structural ring unit called chlorin is similarly complexed with magnesium instead of iron when forming part of the most common forms of chlorophyll molecules, giving them a green color. Another similar macrocycle unit is corrin, which complexes with cobalt when forming part of cobalamin molecules, constituting Vitamin B12, which is intensely red. The corrin unit has six conjugated double bonds but is not conjugated all the way around its macrocycle ring.

|

|

|

| Heme group of hemoglobin | The chlorin section of the chlorophyll a molecule. The green box shows a group that varies between chlorophyll types. | Cobalamin structure includes a corrin macrocycle. |

Chromophores

Conjugated systems form the basis of chromophores, which are light-absorbing parts of a molecule that can cause a compound to be colored. Such chromophores are often present in various organic compounds and sometimes present in polymers that are colored or glow in the dark. Chromophores often consist of a series of conjugated bonds and/or ring systems, commonly aromatic, which can include C–C, C=C, C=O, or N=N bonds.

Conjugated chromophores are found in many organic compounds including azo dyes (also artificial food additives), compounds in fruits and vegetables (lycopene and anthocyanidins), photoreceptors of the eye, and some pharmaceutical compounds such as the following:

See also

- Resonance

- Hyperconjugation

- Cross-conjugation

- Polyene

- Conjugated microporous polymer

- List of conjugated polymers

References and notes

- ^ IUPAC Gold Book - conjugated system (conjugation)

- ^ March Jerry; (1985). Advanced Organic Chemistry reactions, mechanisms and structure (3rd ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons, inc. ISBN 0-471-85472-7

- ^ IUPAC Gold Book - homoconjugation

- ^ Some orbital overlap is possible even between bonds separated by one (or more) CH2 because the bonding electrons occupy orbitals which are quantum-mechanical functions and extend indefinitely in space. Macroscopic drawings and models with sharp boundaries are misleading because they do not show this aspect.

- ^ P. Atkins and J. de Paula Physical Chemistry (8th ed., W.H.Freeman 2006), p.281 ISBN 0-7167-8759-8

- ^ Atkins and de Paula p.398