Cornerstone

The cornerstone (or foundation stone) concept is derived from the first stone set in the construction of a masonry foundation, important since all other stones will be set in reference to this stone, thus determining the position of the entire structure.

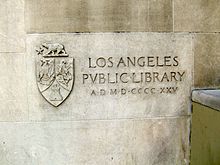

Over time a cornerstone became a ceremonial masonry stone, or replica, set in a prominent location on the outside of a building, with an inscription on the stone indicating the construction dates of the building and the names of architect, builder, and other significant individuals. The rite of laying a cornerstone is an important cultural component of eastern architecture and metaphorically in sacred architecture generally. There are six references to cornerstones in both the Old and New Testaments.

Some cornerstones include time capsules from, or engravings commemorating, the time a particular building was built.

History

Often, the ceremony involved the placing of offerings of grain, wine and oil on or under the stone. These were symbolic of the produce and the people of the land and the means of their subsistence. This in turn derived from the practice in still more ancient times of making an animal or human[1][2] sacrifice that was laid in the foundations.

The origins of this tradition are vague but its presence in Judeo-Christian countries can be associated with at least six quotations from the Old Testament (Job 38:6, Psalm 118:22, Isaiah 19:13, Isaiah 28:16, Jeremiah 51:26, Zechariah 10:4) and also six citations in the New Testament (Matthew 21:42, Mark 12:10, Luke 20:17, Acts 4:11, Ephesians 2:20 and 1 Peter 2:7) and Isaiah 28:16 quoted by the writer of the Book of 1st Peter in chapter 2, verse 6 KJVTemplate:Bibleverse with invalid book. The writer of the Book of Ephesians makes clear that Jesus is the cornerstone, of a faith rather than a building, referred to in the New Testament Ephesians 2:20.[3]

Frazer (2006: p. 106-107) in The Golden Bough charts the various propitiary sacrifices and effigy substitution such as the shadow, states that:

Nowhere, perhaps, does the equivalence of the shadow to the life or soul come out more clearly than in some customs practised to this day in South-eastern Europe. In modern Greece, when the foundation of a new building is being laid, it is the custom to kill a cock, a ram, or a lamb, and to let its blood flow on the foundation-stone, under which the animal is afterwards buried. The object of the sacrifice is to give strength and stability to the building. But sometimes, instead of killing an animal, the builder entices a man to the foundation-stone, secretly measures his body, or a part of it, or his shadow, and buries the measure under the foundation-stone; or he lays the foundation-stone upon the man's shadow. It is believed that the man will die within the year. The Roumanians of Transylvania think that he whose shadow is thus immured will die within forty days; so persons passing by a building which is in course of erection may hear a warning cry, Beware lest they take thy shadow! Not long ago there were still shadow-traders whose business it was to provide architects with the shadows necessary for securing their walls. In these cases the measure of the shadow is looked on as equivalent to the shadow itself, and to bury it is to bury the life or soul of the man, who, deprived of it, must die. Thus the custom is a substitute for the old practice of immuring a living person in the walls, or crushing him under the foundation-stone of a new building, in order to give strength and durability to the structure, or more definitely in order that the angry ghost may haunt the place and guard it against the intrusion of enemies.[4]

In ancient Japan legends talk about Hitobashira (人柱, "human pillar"), in which maidens were buried alive at the base or near some constructions as a prayer to ensure the buildings against disasters or enemy attacks.

Modern practices

In modern practice, normally, a VIP of the organization, or a local celebrity or community leader, will be invited to conduct the ceremony of figuratively beginning the foundations of the building, with the person's name and official position and the date usually being recorded on the stone. This person is usually asked to place their hand on the stone or otherwise signify its laying.

Often still, and certainly until the 1970s, most ceremonies involved the use of a specially manufactured and engraved trowel that had a formal use in laying mortar under the stone. Similarly, a special hammer was often used to ceremonially tap the stone into place.

The foundation stone often has a cavity into which is placed a time capsule containing newspapers of the day or week of the ceremony plus other artifacts that are typical of the period of the construction: coins of the year may also be immured in the cavity or time capsule.[5]

Freemasonry

Freemasons sometimes perform the public cornerstone laying ceremony for notable buildings. This ceremony was described by The Cork Examiner of 13 January 1865 as follows:

...The Deputy Provincial Grand Master of Munster, applying the golden square and level to the stone said ; " My Lord Bishop, the stone has been proved and found to be 'fair work and square work' and fit to be laid as the foundation stone of this Holy Temple".' After this, Bishop Gregg spread cement over the stone with a trowel specially made for the occasion by John Hawkesworth, a silversmith and a jeweller. He then gave the stone three knocks with a mallet and declared the stone to be 'duly and truly laid'. The Deputy Provincial Grand Master of Munster poured offerings of corn, oil and wine over the stone after Bishop Gregg had declared it to be 'duly and truly laid'. The Provincial Grand Chaplain of the Masonic Order in Munster then read out the following prayer: 'May the Great Architect of the universe enable us as successfully to carry out and finish this work. May He protect the workmen from danger and accident, and long preserve the structure from decay; and may He grant us all our needed supply, the corn of nourishment, the wine of refreshment, and the oil of joy, Amen. So mote it be.' The choir and congregation then sang the Hundredth Psalm.[6]

In Freemasonry, which grew from the practice of stonemasons, the initiate (Entered Apprentice) is placed in the north-east corner of the Lodge as a figurative foundation stone.[7] This is intended to signify the unity of the North associated with darkness and the East associated with light.[8]

Ecclesiastical

A cornerstone (Greek: Άκρογωνιεîς, Latin: Primarii Lapidis) will sometimes be referred to as a "foundation-stone", and is symbolic of Christ, whom the Apostle Paul referred to as the "head of the corner" and is the "Chief Cornerstone of the Church" (Ephesians 2:20). Many of the more ancient churches will place relics of the saints, especially martyrs, in the foundation stone.

Western Roman Catholic Churches

According to the pre-Vatican II rite of the Roman Catholic Church: Before the construction of a new church begins, the foundations of the building are clearly marked out and a wooden cross is set up to indicate where the altar will stand. Once preparations have been made, the bishop—or a priest delegated by him for that purpose—will bless holy water and with it sprinkle first the cross that was erected and then the foundation stone itself. Upon the stone he is directed to engrave crosses on each side with a knife, and then pronounce the following prayer: "Bless, O Lord, this creature of stone (creaturam istam lapidis) and grant by the invocation of Thy holy name that all who with a pure mind shall lend aid to the building of this church may obtain soundness of body and the healing of their souls. Through Christ Our Lord, Amen."[9]

After this, the Litany of the Saints is said, followed by an antiphon and Psalm 126 (Psalm 127 in the Hebrew numbering), which appropriately begins with the verse, "Unless the Lord build the house, they labour in vain that build it". Then the stone is lowered into its place with another prayer and again sprinkled with holy water. More antiphons and psalms follow, while the bishop sprinkles the foundations, dividing them into three sections and ending each with a special prayer. Finally, Veni Creator Spiritus is sung, and two short prayers. Then the bishop, if he deems it opportune, sits down and exhorts the people to contribute to the construction, appointments and maintenance of the new church, after which he dismisses them with his blessing and the proclamation of an indulgence.[3]

Eastern Churches

In the Eastern Orthodox Church the blessing of the bishop must be obtained before construction on a new church may commence, and any clergyman who ventures to do so without a blessing can be deposed. The "Rite of the Foundation of a Church" (i.e., the laying of the cornerstone) will differ slightly depending on whether the church is to be constructed of wood or of stone. Even when a church is built of wood, the cornerstone must in fact be made of stone.

The cornerstone is a solid stone cube upon which a cross has been carved. Below the cross, the following words are inscribed:

In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, this church is founded, in honour and memory of (here the name of the patron saint of the new church is inserted); in the rule of (here the name of the ruler is inserted); in the episcopacy of (here the name of the bishop is inserted); in the Year of the World _____ (Anno Mundi), and from the Birth in the flesh of God the Word _____ (Anno Domini).

In the top of the stone a cross-shaped space is hollowed out into which relics may be placed. Relics are not required, but they are normally placed in the cornerstone. If no relics are inserted in the stone, the inscription may be omitted, but not the cross.

After the foundations for the new church have been dug and all preparations finished, the bishop (or his deputy) with the other clergy vest and form a crucession to the building site. The service begins with a moleben and the blessing of holy water. Then a cross is erected in the place where the Holy Table (altar) will stand, and the cornerstone is consecrated and set in place.[10][11]

See also

References

- ^ Jarvis, William E. (2002), Time Capsules: A Cultural History, McFarland & Company, p. 105, ISBN 978-0-7864-1261-7

- ^ Hastings, James; Selbie, John Alexander; Gray, Louis Herbert (1914), Encyclopaedia of Religion and Ethics, vol. VI., New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 863

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Thurston, Herbert (1912), "Corner Stone", The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. XIV, New York: Robert Appleton Company, retrieved 2007-08-02

- ^ The Golden Bough - James George Frazer - Google Boeken. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

- ^ Kleisner, Tomas (1970-01-01). "An Unknown Medal for the Foundation of Susice Monastery, 1651 | Tomas Kleisner". Academia.edu. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

- ^ "Saint Fin Barre's Cathedral > Cork Past and Present". Corkpastandpresent.ie. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

- ^ Duncan, Malcolm C. Duncan's Ritual of Freemasonry David McKay Company, NY

- ^ Symbolism of Freemasonry: Its Science, Philosophy, Legends, Myths, and Symbolism - Albert Gallatin Mackey - Google Books. Books.google.com.au. Retrieved 2013-11-07.

- ^ Pontificale Romanum, Fasc. III, "De Benedictione et Impositione primarii Lapidis pro Ecclesia aedificanda"

- ^ Hapgood, Isabel (1975), "The Office Used at the Founding of a Church (the Laying of the Corner-Stone)", Service Book of the Holy Orthodox-Catholic Apostolic Church (5th Ed.), Englewood, NJ: Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese, p. 479

- ^ Sokolof, Archpriest D. (2001), "The Order of the Consecration of a Church", A Manual of the Orthodox Church's Divine Services (3rd printing, re-edited), Jordanville, NY: Printshop of St. Job of Pochaev, p. 136

External links

- Blessing and laying Foundation Stone (Malankara Syriac Orthodox Church)

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.