Cursive

Cursive, also known as longhand, script, handwriting, looped writing, joined-up writing, joint writing, or running writing is any style of penmanship in which the symbols of the language are written in a conjoined and/or flowing manner, generally for the purpose of making writing faster. Formal cursive is generally joined, but casual cursive is a combination of joins and pen lifts. The writing style can be further divided as "looped", "italic", or "connected".

The cursive method is used with a number of alphabets due to its improved writing speed and infrequent pen lifting. In some alphabets, many or all letters in a word are connected, sometimes making a word one single complex stroke.

Descriptions

Cursive is any style of penmanship in which the symbols of the language are written in a conjoined and/or flowing manner, generally for the purpose of making writing faster. This writing style is distinct from "printscript" using block letters, in which the letters of a word are unconnected and in Roman/Gothic letterform rather than joined-up script. Not all cursive copybooks join all letters: formal cursive is generally joined, but casual cursive is a combination of joins and pen lifts. In the Arabic, Syriac, Latin, and Cyrillic alphabets, many or all letters in a word are connected, sometimes making a word one single complex stroke. In Hebrew cursive and Roman cursive, the letters are not connected.

Subclasses

Looped

In looped cursive penmanship, some ascenders and descenders have loops which provide for joins.

Italic

Cursive italic penmanship—derived from chancery cursive—uses non-looped joins or no joins. In italic cursive, there are no joins from g, j, q or y, and a few other joins are discouraged.[1][failed verification] Italic penmanship became popular in the 15th-century Italian Renaissance. The term "italic" as it relates to handwriting is not to be confused with italic typed letters that slant forward. Many, but not all, letters in the handwriting of the Renaissance were joined, as most are today in cursive italic.

Origin

The origin of the cursive method is associated with practical advantages of writing speed and infrequent pen lifting to accommodate the limitations of the quill. Quills are fragile, easily broken, and will spatter unless used properly. Steel dip pens followed quills; they were sturdier, but still had some limitations. The individuality of the provenance of a document (see Signature) was a factor also, as opposed to machine font.[2]

The term cursive derives from the 18th century Italian corsivo from Medieval Latin cursivus, which literally means running. This term in turn derives from Latin currere ("to run, hasten").[3]

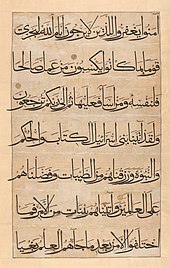

Arabic

In the Arabic script, most letters of any given word are joined to one another in a continuous flowing line. Thus, there is in effect no distinction between cursive and non-cursive forms of Arabic, only individual variations which amount to calligraphy (a highly developed art in the Arab world).

Bengali

In Bengali cursive script[citation needed] (also known in Bengali as "professional writing"[citation needed]) the letters are more likely to be more curvy in appearance than in standard Bengali handwriting. Also, the horizontal supporting bar on each letter (matra) runs continuously through the entire word, unlike in standard handwriting. This cursive handwriting often used by literature experts, differs in appearance from the standard Bengali alphabet as it is free hand writing similar to Japanese calligraphy, where sometimes the alphabets are complex and appears different from the standard handwriting.[citation needed]

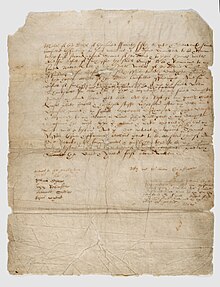

Roman

Roman cursive is a form of handwriting (or a script) used in ancient Rome and to some extent into the Middle Ages. It is customarily divided into old (or ancient) cursive, and new cursive. Old Roman cursive, also called majuscule cursive and capitalis cursive, was the everyday form of handwriting used for writing letters, by merchants writing business accounts, by schoolchildren learning the Latin alphabet, and even by emperors issuing commands. New Roman cursive, also called minuscule cursive or later Roman cursive, developed from old Roman cursive. It was used from approximately the 3rd century to the 7th century, and uses letter forms that are more recognizable to modern eyes; "a", "b", "d", and "e" have taken a more familiar shape, and the other letters are proportionate to each other rather than varying wildly in size and placement on a line.

Greek

The Greek alphabet has had several cursive forms in the course of its development. In antiquity, a cursive form of handwriting was used in writing on papyrus. It employed slanted and partly connected letter forms as well as many ligatures. Some features of this handwriting were later adopted into Greek minuscule, the dominant form of handwriting in the medieval and early modern era. In the 19th and 20th centuries, an entirely new form of cursive Greek, more similar to contemporary Western European cursive scripts, was developed.

English

Cursive writing was used in English before the Norman conquest. Anglo-Saxon Charters typically include a boundary clause written in Old English in a cursive script. A cursive handwriting style—secretary hand—was widely used for both personal correspondence and official documents in England from early in the 16th century.

Cursive handwriting developed into something approximating its current form from the 17th century, but its use was neither uniform, nor standardized either in England itself or elsewhere in the British Empire. In the English colonies of the early 17th century, most of the letters are clearly separated in the handwriting of William Bradford, though a few were joined as in a cursive hand. In England itself, Edward Cocker had begun to introduce a version of the French rhonde style, which was then further developed and popularized throughout the British Empire in the 17th and 18th centuries as round hand by John Ayers and William Banson.[5]

In the American colonies, on the eve of their independence from the Kingdom of Great Britain, it is notable that Thomas Jefferson joined most, but not all of the letters when drafting the United States Declaration of Independence. However, a few days later, Timothy Matlack professionally re-wrote the presentation copy of the Declaration in a fully joined, cursive hand. Eighty-seven years later, in the middle of the 19th century, Abraham Lincoln drafted the Gettysburg Address in a cursive hand that would not look out of place today.

Note that not all such cursive, then or now, joined all of the letters within a word.

In both the British Empire and the United States in the 18th and 19th centuries, before the typewriter, professionals used cursive for their correspondence. This was called a "fair hand", meaning it looked good, and firms trained their clerks to write in exactly the same script.

In the early days of the post office, letters were written in cursive – and to fit more text on a single sheet, the text was continued in lines crossing at 90 degrees from the original text.[6] Block letters were not suitable for this.[citation needed]

Although women's handwriting had noticeably different particulars from men's, the general forms were not prone to rapid change. In the mid-19th century, most children were taught the contemporary cursive; in the United States, this usually occurred in second or third grade (around ages seven to nine). Few simplifications appeared as the middle of the 20th century approached.[citation needed]

After the 1960s, a movement originally begun by Paul Standard in the 1930s to replace looped cursive with cursive italic penmanship resurfaced. It was motivated by the claim that cursive instruction was more difficult than it needed to be: that conventional (looped) cursive was unnecessary, and it was easier to write in cursive italic. Because of this, a number of various new forms of cursive italic appeared, including Getty-Dubay, and Barchowsky Fluent Handwriting.

The decline of English cursive in the United States

Starting in the 1930s and 1940s, colleges discarded the teaching of handwriting techniques from curriculum. Students in college at that time therefore lacked the handwriting skills and ways to teach handwriting. Those who went into education at the time did not value cursive as much as the generation before them, and they were unsuccessful in passing the skills to the next generation. In addition to the new technology that would become popular over the following decades, cursive seemed inefficient compared to the technology that could produce information more quickly. One of the earliest forms of new technology that caused the decline of handwriting was the invention of the ballpoint pen patented in 1888 by John Loud. Two brothers, Laszlo and Gyorgy Biro further developed the pen by changing the design and using different ink that dried quickly. With their design, it was guaranteed that the ink would not smudge, as it would with the earlier design of pen and it no longer required the careful penmanship one would use with the older design of pen. The ballpoint pen was mass-produced and sold for a cheap price, changing the way people wrote. Over time the emphasis of using the style of cursive to write slowly declined, only to be later impacted by other technologies.[7][8]

Throughout recent years cursive has been on a downward slope due to its lack of necessity. It has been an open topic whether cursive could be soon removed from all schools. Most of school is geared toward helping students pass and take whichever route in life they choose, whether it may be college or going straight to the workforce. No option out of school requires a student to know cursive. Furthermore, teachers prepare students for using computers in their future, and cursive writing is generally thought to be of little value. The FairFax Education Association is the biggest teachers union in the country and even they have called cursive a “dying art.” Common Core for most educational institutes is to let teachers teach what is required and tested through various standardized tests. Thus, rendering cursive non-essential when it comes to a student trying to graduate from their various high schools, what makes this most important is that the “No Child Left Behind” law does not test schools on cursive also meaning that most teachers, teach toward their respective standardized test. Simply put however, many consider cursive too tedious to learn and believe that it is not useful in the long run for school.[9][10]

On the 2006 SAT, a United States post-secondary education entrance exam, only 15 percent of the students wrote their essay answers in cursive.[11]

In a 2007 survey of 200 teachers of first through third grades in all 50 American states, 90 percent of respondents said their schools required the teaching of cursive.[12]

A 2008 nationwide survey found elementary school teachers lacking formal training in teaching handwriting to students. Only 12 percent of teachers reported having taken a course in how to teach it.[13]

In 2012, the American states of Indiana and Hawaii announced that their schools will no longer be required to teach cursive (but will still be permitted to), and instead will be required to teach "keyboard proficiency". As of 2011 the same was true of Illinois. Since the nationwide proposal of the Common Core State Standards in 2009, which do not include instruction in cursive, the standards have been adopted by 44 states as of July 2011, all of which have debated whether to augment them with cursive.[14][15]

Conservation efforts and cognitive benefits

Many essential documents in the United States require signatures, which are conventionally in cursive handwriting. Additionally, many historical documents, such as the United States Constitution, are written in cursive—the inability to read cursive therefore precludes one from being able to fully appreciate such documents in their original format.[16] Despite the decline in the day-to-day use of cursive, it is being reintroduced to the curriculum of schools in the United States. States such as California, Idaho, Kansas, Massachusetts, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee have already mandated cursive in schools as a part of the Back to Basics program designed to maintain the integrity of cursive handwriting.[17] Some[who?] argue that cursive is not worth teaching in schools and "in the 1960s cursive was implemented because of preference and not an educational basis; Hawaii, Indiana, and Illinois have all replaced cursive instruction with 'keyboard proficiency' and 44 other states are currently weighing similar measures."[18][attribution needed]

With the widespread use of computers which has nearly taken the handwritten word to extinction, researchers set out to test the effectiveness of both mediums. In a study done by Pam Mueller which compared scores of students who took notes by hand and via laptop computer showed that students who took notes by hand showed advantages in both factual and conceptual learning.[19] Another study done by Anne Mangen showed that children showed an acceleration in learning new words when they wrote them by hand rather than on a computer screen.[20] Learning to write in cursive is a stepping stone to developing neat handwriting and in a third study conducted by Florida International University, professor Laura Dinehart concluded that students with neater handwriting tend to develop better reading and writing skill, though it is difficult to conclude causation from such an association.[9] Aside from these cognitive benefits, students with dyslexia, who have difficulty learning to read because their brains associate sounds and letter combinations inefficiently have found that cursive can help them with the decoding process because it integrates hand-eye coordination, fine motor skills and other brain and memory functions.[21]

German

Up to the 19th century, Kurrent (also known as German cursive) was used in German language longhand. Kurrent was not used exclusively, but in parallel to modern cursive (which is the same as English cursive). Writers used both cursive styles: location, contents and context of the text determined which style to use. A successor of Kurrent, Sütterlin, was widely used in the period 1911-1941 until the Nazi Party banned it, and German speakers brought up with Sütterlin continued to use it well into the post-war period.

Today, three different styles of cursive writing are taught in German schools, the Lateinische Ausgangsschrift (introduced in 1953), the Schulausgangsschrift (1968), and the Vereinfachte Ausgangsschrift (1969).[22] The German National Primary Schoolteachers' Union has proposed replacing all three with Grundschrift, a simplified form of non-cursive handwriting adopted by Hamburg schools.[23]

Russian

The Russian Cursive Cyrillic alphabet is used (instead of the block letters) when handwriting the modern Russian language. While several letters resemble Latin counterparts, many of them represent different sounds. Most handwritten Russian, especially personal letters and schoolwork, uses the cursive Russian (Cyrillic) alphabet. Most children in Russian schools are taught in the 1st grade how to write using this Russian script.

Chinese

Cursive forms of Chinese characters are used in calligraphy; "running script" is the semi-cursive form and "grass script" is the cursive. The running aspect of this script has more to do with the formation and connectedness of strokes within an individual character than with connections between characters as in Western connected cursive. The latter are rare in Hanzi and the derived Japanese Kanji characters which are usually well separated by the writer.

-

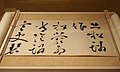

Semi-cursive style Calligraphy of Chinese poem by Mo Ruzheng

-

classical poem in cursive script at Treasures of Ancient China exhibit

-

8 cursive characters for dragon

-

Calligraphy of both cursive and semi-cursive by Dong Qichang

-

Four columns in cursive script quatrain poem, Quatrain on Heavenly Mountain. Attributed to Emperor Gaozong of Song, the tenth Chinese Emperor of the Song Dynasty

-

One page of the album "Thousand Character classic in formal and Cursive script" attributed to Zhi Yong

Examples

-

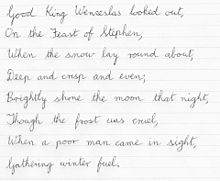

Example of classic American business handwriting known as Spencerian script from 1884.

-

Table of 19th-century Greek cursive letter forms.

See also

- Cursive script (East Asia) (Grass script)

- D'Nealian Script

- Emphasis (typography)

- Hieratic and Cursive hieroglyphs

- Palmer Method

- Paper

- Pen

- Penmanship

- Shorthand

- Spencerian script

- Sütterlin and Kurrent - German Cursive Template:Nb10

Notes

- ^ Bounds, Gwendolyn (October 5, 2010). "How Handwriting Boosts the Brain". The Wall Street Journal. New York: Dow Jones. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

- ^ Georges Jean (1997). Writing: The story of alphabets and scripts, London: Thames and Hudson Ltd. [New Horizons]

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "cursive". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- ^ Cardenio, Or, the Second Maiden's Tragedy, pp. 131-3: By William Shakespeare, Charles Hamilton, John Fletcher (Glenbridge Publishing Ltd., 1994) ISBN 0-944435-24-6

- ^ Whalley, Joyce Irene (1980). The Art of Calligraphy, Western Europe & America. London: Bloomsbury. p. 400. ISBN 0-906223-64-4.

- ^ Livingston, Ira (1997). "The Romantic Double-Cross: Keats's Letters". Arrow of Chaos: Romanticism and Postmodernity. University of Minnesota Press. p. 143. ISBN 0816627959.

- ^ "How The Ballpoint Pen Killed Cursive". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- ^ Enstrom, E.A. (1965). "The Decline of Handwriting". The Elementary School Journal.

- ^ a b Shapiro, T. Rees (2013-04-04). "Cursive handwriting is disappearing from public schools". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- ^ "The End of the Line for Cursive?". ABC News. 2011-01-25. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- ^ "The Handwriting Is on the Wall". Washington Post. 11 October 2006.

- ^ "Schools debate: Is cursive writing worth teaching?". USA Today. 23 January 2009.

- ^ Graham, Steve; Harris, Karen R.; Mason, Linda; Fink-Chorzempa, Barbara; Moran, Susan; Saddler, Bruce (February 2008). "How do primary grade teachers teach handwriting? A national survey". Reading and Writing. 21 (1–2). New York: Springer Netherlands: 49–69. doi:10.1007/s11145-007-9064-z. ISSN 0922-4777. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ^ Webley, Kayla (6 July 2011). "Typing Beats Scribbling: Indiana Schools Can Stop Teaching Cursive". TIME Newsfeed. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ "Hawaii No Longer Requires Teaching Cursive In Schools". Huffpost Education. 1 August 2011.

- ^ Steinmetz, Katy. "Five Reasons Kids Should Still Learn Cursive Writing". TIME.com. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- ^ "Is cursive handwriting slowly dying out in America?". PBS NewsHour. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- ^ "Is Cursive Handwriting Going Extinct?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- ^ Mueller, Pam (2014). "The Pen Is Mightier Than the Keyboard: Advantages of Longhand Over Laptop Note Taking". Psychological Science. doi:10.1177/0956797614524581.

- ^ Mangen, Anne (2015). "Handwriting versus Keyboard Writing: Effect on Word Recall". Journal of Writing Research.

- ^ "How cursive can help students with dyslexia connect the dots". PBS NewsHour. Retrieved 2015-10-30.

- ^ "Grundschrift-Schreibschrift". grundschrift-schreibschrift.de.

- ^ Helen Pidd. "German teachers campaign to simplify handwriting in schools". the Guardian.

External links

- Lessons in Calligraphy and Penmanship, including scans of classic nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century manuals and examples

- The Golden Age of American Penmanship, including scans of the January 1932 issue of Austin Norman Palmer's American Penman

- Normal and Bold Victorian Modern Cursive electronic fonts for downloading

- Mourning the Death of Handwriting, a TIME Magazine article on the demise of cursive handwriting

- Op-Art: The Write Stuff, a New York Times article on the advantages of Italic hand over both full cursive and block printing

- The Society for Italic Handwriting, supporters of teaching a simplified cursive hand

- Cursive-Fonts, online resource for cursive fonts in ttf format

- Has Technology Killed Cursive Handwriting?—Mashable, June 11, 2013

- Why Cursive Still Matters in Education