Damrong Rajanubhab

| Tisavarakumarn | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prince of Siam, Prince Damrong Rajanubhab | |||||

HRH Prince Ditsawarakuman, Prince Damrong Rajanubhab | |||||

| Born | 21 June 1862 Bangkok, Siam | ||||

| Died | 1 December 1943 (aged 81) Bangkok, Thailand | ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Chakri | ||||

| Father | King Mongkut | ||||

| Mother | Consort Chum | ||||

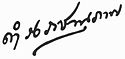

| Signature |  | ||||

Tisavarakumarn Damrong Rajanubhab (สมเด็จพระเจ้าบรมวงศ์เธอ พระองค์เจ้าดิศวรกุมาร กรมพระยาดำรงราชานุภาพ; RTGS: Ditsawarakuman Damrongrachanuphap[Note 1]) (21 June 1862 – 1 December 1943) was the founder of the modern Thai education system as well as the modern provincial administration. He was also an autodidact (self-taught) historian, and one of the most influential intellectuals of his time.

Born as Phra Ong Chao Tisavarakumarn (พระองค์เจ้าดิศวรกุมาร; "Prince Tisavarakumarn"), a son of King Mongkut with Consort Chum (เจ้าจอมมารดาชุ่ม; Chao Chom Manda Chum), a lesser royal wife; he initially learned Thai and Pali from private tutors, and English at the Royal School with Mr Francis George Patterson. At the age of 14, he received his formal education in a special palace school created by his half-brother, King Chulalongkorn. He was given posts in the royal administration at an early age, becoming the commander of the Royal Guards Regiment in 1880 at age 18, and after several years working in building army schools as well as modernizing the army in general. In 1887, he was appointed as Grand-officer to the army (commander-in-chief). At the same time he was chosen by the king to become the Minister of Education in his provisional cabinet. However, when King Chulalongkorn began his administrative reform programme in 1892, Prince Damrong was chosen to lead the Ministry of the North (Mahatthai), which was converted into the Ministry of the Interior in 1894.

In his time as minister, he completely overhauled the provincial administration. Many minor provinces were merged into larger ones, the provincial governors lost most of their autonomy when the post was converted into one appointed and salaried by the ministry, and a new administrative division – the monthon (circle) covering several provinces – was created. Also, the formal education of administrative staff was introduced. Prince Damrong was among the most important advisors of the king, and considered second only to him in power.

Political climate in Siam (1855–1893)

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2013) |

- For further information, see: Gustave Rolin-Jaequemyns #Situation in Siam

Legal traditions made little if any sense to foreigners.[1] Nor did they have knowledge of the ancient political climate.[2] Nor aware that the Bowring Treaty, which nearly all considered a significant advancement, had accomplished none of its objectives and had been set-back for the Siamese for the ensuing decades.[3] Monthon reforms met with resistance, complicated by French interference in Siamese authority.[4]

Foreign advisers

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2013) |

Prince Damrong went in search of a European General Advisor for the king by way of the Suez Canal. In December 1891, during a lunch hosted by the British ambassador to Egypt, Damrong met Gustave Rolin-Jaequemyns, who had edited the first issue of Revue de Droit International et de Législation Comparée ("Review of International Law and Comparative Legislation"), which had appeared late 1868 with contributions from many noted scholars. Following a hasty correspondence with Bangkok, the prince was able to offer Rolin-Jaequemyns an annual salary of ₤3000. Among his successors were Edward Strobel, the first American Adviser in Foreign Affairs, followed with lesser titles by Jens Westengard, Eldon James and Francis B. Sayre. Strobel, Westengard, James and Sayre were all Harvard Law Professors.[5]

Later years

After the death of King Chulalongkorn in 1910, the relationship with his successor King Vajiravudh was less smooth. Prince Damrong finally resigned in 1915 from his post at the ministry, officially due to health problems, since otherwise the resignation would have looked like an affront against the absolute monarch.

During the brief reign of King Prajadhipok, the prince proposed that the king founded the Royal Institute, mainly to look after the National Library and the museums. He became the first President of the Royal Institute of Thailand. He was given the title Somdet Phra Chao Borommawong Thoe Krom Phraya Damrong Rajanubhab by King Prajadhipok in recognition to his works. This became the name by which he is generally known.

In the following years Damrong worked as a self-educated historian, as well as writing books on Thai literature, culture and arts. Out of his works grew the National Library, as well as the National Museum.

Being one of the main apologists of absolute monarchy, after the Siamese revolution of 1932 which introduced Constitutional monarchy in the kingdom, Damrong was exiled to Penang in British Malaysia. In 1942, after the old Establishment had substantially regained power from the 1932 reformists, he was allowed to return to Bangkok, where he died one year later.

Prince Damrong is credited as the father of Thai history, the education system, the health system (the Ministry of Health was originally a department of the Ministry of the Interior) and the provincial administration. He also had a major role in crafting Bangkok's anti-democratic state ideology of "Thainess".[citation needed]

On the centenary of his birth in 1962, he became the first Thai to be included in the UNESCO list of the world's most distinguished persons. On 28 November 2001, to honour the remarkable contributions the prince made to the country, the government declared that 1 December would thereafter be known as "Damrong Rajanupab Day".[6]

His many descendants use the Royal surname Tisakula (Template:Lang-th.)

Writings

Prince Damrong wrote countless books and articles, of which only a few are available in English translation:

- Our Wars with the Burmese: Thai-Burmese Conflict 1539–1767, ISBN 974-7534-58-4

- Journey through Burma in 1936: A View of the Culture, History and Institutions, ISBN 974-8358-85-2

- H. R. H. Prince Damrong (1904). "The Foundation of Ayuthia" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. JSS Vol. 1.0e (digital). Siam Heritage Trust. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|nopp=(help) - Wright, Arnold (2008) [1908]. Wright, Arnold; Breakspear, Oliver T (eds.). Twentieth century impressions of Siam (PDF 65.3 MB). London&c: Lloyds Greater Britain Publishing Company.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) for which Prince Damrong offered advice and images

See also

Notes

- ^ Full transcription is "Somdet Phrachao Borommawongthoe Phra-ongchao Ditsawarakuman Kromphraya Damrongrachanuphap" (สมเด็จพระเจ้าบรมวงศ์เธอ พระองค์เจ้าดิศวรกุมาร กรมพระยาดำรงราชานุภาพ)

References

- ^ Sarasin Viraphol (1977). "Law in traditional Siam and China: A comparative study" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. JSS Vol. 65.1 (digital). Siam Heritage Trust: image 2. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

This represents the incorporation of natural law (jus naturale) into the positive law (jus gentium) of the ruler, making the pouvoir arbitraire the sole legal principle for government.

- ^ Sunait Chutintaranond (1990). "Mandala, Segmentary State and Politics of Centralization in Medieval Ayudhya" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. JSS Vol. 78.1i (digital). Siam Heritage Trust. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

...I am interested in the ways in which Kautilya's theory of mandala has been interpreted by historians for the purpose of studying ancient states in South and Southeast Asia.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|nopp=(help) - ^ Terwiel, B.J. (1991). "The Bowring Treaty: Imperialism and the Indigenous Perspective" (free PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. JSS Vol. 79.2f (digital). Siam Heritage Trust: image. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

In this paper the evidence upon which historians have based their statements on the Treaty's economic results is examined. It will be shown that all take their cue from Bowring's own words. Secondly it will be shown that Bowring's remarks are not necessarily a reliable indicator.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|nopp=(help) - ^ Murdoch, John B. (1974). "The 1901-1902 Holy Man's Rebellion" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. JSS Vol.62.1 (digital). Siam Heritage Trust. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|nopp=(help) - ^ Oblas, Peter (1972). "Treaty Revision and the Role of the American Foreign Affairs Adviser 1909-1925" (free). Journal of the Siam Society. JSS Vol. 60.1 (digital). Siam Heritage Trust: images 2–4, 7–9. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

In the course of his service, Sayre was awarded the Grand Cross of the Crown of Siam. The title of Phya Kalyanamaitri was also bestowed upon him.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|nopp=(help) - ^ "Man of many talents". Prince Damrong. Ministry of Interior (Thailand). 5 March 2010. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

Additional reading

- Biography from the Encyclopedia of Asian History

- Chachai Khumthawiphon (1991). สมเด็จฯ กรมพระยาดำรงราชานุภาพและประวัติศาสตร์นิพนธ์ไทยสมัยใหม่: การวิเคราะห์เชิงปรัชญา (pdf) (in Thai). Bangkok: Thammasat University Press.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - Masao, T. (Toshiki Masao) (1905). "Researches into Indigenous Law of Siam as a study of Comparative Jurisprudence" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. JSS Vol.2.1e. (digital). Siam Heritage Trust. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- Prince Damrong's Foundation (1978). The Illustrated Biography of His Royal Highness Prince Damrong Rajanupab (pdf) (in Thai and English). Bangkok: Fine Arts Department of Thailand.

- Tej Bunnag (1977). The provincial administration of Siam, 1892–1915: the Ministry of the Interior under Prince Damrong Rajanubhab. Kuala Lumpur; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-580343-4.

- Use dmy dates from December 2011

- Thai princes

- Phra Ong Chao

- Chakri Dynasty

- House of Disakul

- Chulalongkorn family

- Thai historians

- Historians of Thailand

- Knights of the Order of the Royal House of Chakri

- Knights of the Order of the Nine Gems

- Knights Grand Cordon of the Order of Chula Chom Klao

- Knights of the Ratana Varabhorn Order of Merit

- Knights Grand Cordon of the Order of the Crown of Thailand

- 1862 births

- 1943 deaths