Dimple

| |

|---|---|

Bilateral cheek dimples | |

| Anatomical terminology |

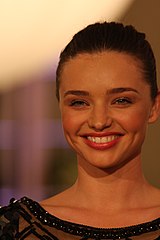

A dimple (also known as a gelasin)[1] is a small natural indentation in the flesh on a part of the human body, most notably in the cheek. Numerous cultures believe that cheek dimples are a good luck charm that entices people who think they are physically attractive, but they are also associated with heroism and innocence, which has been included in literature for many centuries.

Medical research debates whether cheek dimples can be inherited or which type of allele they are, but it is certain that humans with cheek dimples are more likely to have them in both cheeks. Depth and length appearances are affected by the shape of the skull and dimples can appear and disappear due to age. There are four types of facial dimples, including cheek, and the cleft chin (sometimes nicknamed a "chin dimple").

Overview

Cheek dimples when present, show up when a person makes a facial expression, such as smiling, whereas a chin dimple is a small line on the chin that stays on the chin without making any specific facial expressions. Dimples may appear and disappear over an extended period;[2] a baby born with dimples in their cheeks may lose them as they grow into a child due to their diminishing baby fat.[3]

Anatomy

Dimples are usually located on mobile tissue,[4][5] and are possibly caused by variations in the structure of the facial muscle known as zygomaticus major. Specifically, the presence of a double or bifid zygomaticus major muscle may explain the formation of cheek dimples.[6] This bifid variation of the muscle originates as a single structure from the zygomatic bone. As it travels anteriorly, it then divides with a superior bundle that inserts in the typical position above the corner of the mouth. An inferior bundle inserts below the corner of the mouth.

Cheek dimples can occur in any person, but some studies have suggested that dimples (both cheek and chin) are more common in females.[7][8] They can be either permanent,[9] or transient (aging makes dimples appear/disappear due to facial development and muscle growth):[9] a Greek study spanning almost 20 years concluded that 34% of Greek adults had dimples whereas 13% of Greek youths (between 7 and 15 years old) had dimples as well,[10] which might suggest that transient dimples are more common than permanent.[11]

Professor John McDonald, citing limited research, concluded that dimples have been mislabeled as genetically inherited and as a dominant trait.[6][12] It is believed that cheek dimple genes occur on the 16th chromosome, whereas cleft chin genes occur on the 5th.[13] However, the University of Utah considers dimples an "irregular" dominant trait that is probably controlled mostly by one gene but is influenced by other genes.[14]

Characteristics

Having bilateral dimples (dimples in both cheeks) is the most common form of cheek dimples.[15] In a 2018 study of 216 people aged 18–42 with both unilateral (one dimple) and bilateral, 120 (55.6%) had dimples in both of their cheeks.[15] It was originally concluded that 60% of people with one dimple likely have it in their left cheek,[16] but later research concluded that 53% were on the right,[15] however, this may be due to differing cultures. Dimples are analogous and how they form in cheeks varies from person to person.[17] Dimple depth and size can also vary; unilateral dimples are usually large,[18] and a possible 12.8% of bilateral people have dimples positioned asymmetrically.[19] They are not linked with a dimpled chin: a study from 2010 by the University of Ilorin examined 500 Yoruban Nigerians with both uni- and bilateral cheek dimples, discovering that only 36 (7.2%) had a cleft chin as well.[20]

The shape of a person's face can affect the look and form as well:[21] leptoprosopic (long and narrow) faces have long and narrow dimples, and euryprosopic (short and broad) faces have short, circular dimples.[21] People with a mesoprosopic face are more likely to have dimples in their cheeks than any other face shape.[22] Singaporean plastic surgeon Khoo Boo-Chai (1929–2012) determined that a cheek dimple occurs on the intersecting line between the corner of the mouth and the outer canthi of the eye,[23] (nicknamed the "KBC point" in dimple surgery)[24] but people with natural dimples do not always have their dimples on the KBC point.[25] The other common type of facial dimple form near the mouth in three types: lower para-angle (underneath the mouth and lips), para-angle ("around the mouth angle"),[26] and upper para-angle (above the mouth and lips).[27]

Society and culture

Cheek dimples are often associated with youth and beauty and are seen as an attractive quality in a person's face, accentuating smiles and making the smile look more cheerful and memorable.[28] Throughout numerous cultures and history, there have been superstitions based on dimples: Chinese culture believes that cheek dimples are a good luck charm[29][30] (particularly, children born with them are seen as pleasant, polite and enthusiastic),[31] but can lead to complicated romantic relationships;[31] and a proverb (often incorrectly credited to Pope Paul VI)[32] argues "A dimple in your cheek/Many hearts you'll seek/A dimple in your chin/The devil within".[33] According to Candy Bites: The Science of Sweets, the dent in Junior Mints is based on this belief, arguing that a unilateral dimple is more attractive than bilateral.[34] Richard Steele wrote that a dimpled laugh "is practised to give a grace to the features, and is frequently made a bait to entangle a gazing lover; this was called by the ancients the Chian laugh."[35] He added: "The prude hath a wonderful esteem for the Chian laugh or dimple [...] and is never seen upon the most extravagant jests to disorder her countenance with the ruffle of a smile [but] very rarely takes the freedom to sink her cheek into a dimple" implying that dimples are alluring due to demure women that have them.[35]

The Englishwoman's Magazine from 1866 featured an article named "The Human Form Divine: Dimples and Wrinkles", which associated cheek dimples with youth. On transient dimples, it wrote: "But generally, dimples mark the departure of youth, and fade away at the approach of crow's feet";[36] "Did you ever see a pretty child's face without dimples in it? Dimples in the cheek—temping dimples—and a dimple in the chin that gave a roguish smartness to the face?"[36] British boxer-turned-Hollywood actor Reginald Denny had his cheek dimples gushed about in a Photoplay article, which Professor Michael Williams inferred that "dimples might also provide a humanizing touch"[37] in the handsome Denny who had "dimples in conjunction with the physique of a young Greek god[.]"[37]

Women without dimples are said to envy the women that have them because dimples are "pitfalls for the men" that "[are] something purely natural and unattainable by art".[36] This has led to artificial attempts to create them: the Ohio-based Dolly Dimpler company advertized in Photoplay about a device that created dimples in customers' cheeks;[38] in 1936, Isabella Gilbert invented the Dimple Maker, a face-fitting brace which pushed dents into the cheeks to emulate dimples,[39] but it is unknown whether the artificial dimples could last this way (the American Medical Association argued that frequent users could develop cancer);[40] and in the 21st century, people undergo dimple surgery.[41]

In fiction

The sentiments appear in fiction: authors have described dimples in their characters for centuries to show beauty,[42] especially in women, which has been seen as part of their sex appeal.[42] This is possibly why cheek dimples have been identified with female characters: Anne from Anne of Green Gables envied other female characters' dimples,[43] whereas Wives and Daughters featured a paragraph about Molly wondering whether she was beautiful as she looked in her mirror, which was followed by: "She would have been sure if, instead of inspecting herself with such solemnity, she had smiled her own sweet merry smile, and called out the gleam of her teeth, and the charm of her dimples."[44] Scarlett O'Hara exploited her cheek dimples in Gone with the Wind when she was flirting to get her own way,[45][46] to the point where Rhett is implied to be aware of what she is doing.[47]

Shakespeare often acknowledged cheek dimples, usually on children, such as "the pretty dimples of [the baby boy's] chin and cheek" in The Winter's Tale or the "pretty dimpled boys, like smiling Cupids" from Antony and Cleopatra;[42] however, Adonis' in Venus and Adonis are mentioned from the point of view of the flirting Venus. There are theories that some of his famous female protagonists had them as well, such as Juliet Capulet,[42][36] "Jessica and Maria [and] Rosalind."[36]

See also

- Cleft chin — also known as a "chin dimple"

- Dimples of Venus — nickname for dimples in the lower back, which are portrayed as physically attractive

- Mendelian traits in humans

- Sacral dimple — lower back dimples

- Skin dimple

References

Citations

- ^ Garg, Anu. "A.Word.A.Day". Wordsmith. Retrieved 2013-08-12.

- ^ Wiedemann Hans-Rudolf (July 1990). "Cheek Dimples". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 36 (3): 376. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320360337. PMID 2363446.

- ^ "Are facial dimples determined by genetics?". Genetics Home Reference. U. S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ Cummins, H (1966). Morris' Human Anatomy (12 ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Book Co. p. 112. ASIN B002JHKLHE.

- ^ Almaary et al. (2018), p. 22

- ^ a b Pessa, Joel E.; Zadoo, Vikram P; Garza, Peter A; Adrian Jr, Erle K; Dewitt, Adriane I; Garza, Jaime R (1998). "Double or bifid zygomaticus major muscle: anatomy, incidence, and clinical correlation". Clinical Anatomy. 11 (5): 310–3. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2353(1998)11:5<310::AID-CA3>3.0.CO;2-T. PMID 9725574.

- ^ Almaary et al. (2018), p. 23: "Among the 120 individuals with bilateral dimples, 99 (82.5%) were female and 21 (17.5%) were male. Regarding the 96 participants with unilateral dimples, 72 (75%) were female and 24 (25%) were male."

- ^ Omotoso, Adeniyi & Medubi (2010), p. 242: "7.2% of the [Nigerian] population studied had both cheek dimples and chin dimple, as it was found to be present in a total of 36 out of 500 south-western Nigerians. The incidence was higher in females (n=22; 4.4%) than males (n=14; 2.8%)."

- ^ a b Omotoso, Adeniyi & Medubi (2010), p. 241

- ^ Abrahams, Marc (July 5, 2005). "Greek Cheek". The Guardian. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

- ^ Pentzos-DaPonte, Athena; Vienna, Alessandro; Brant, Larry; Hauser, Gertrude (October 2004). "Cheek dimples in Greek children and adolescents". International Journal of Anthropology. 19 (4): 289–295. doi:10.1007/BF02449856. S2CID 85295663.

- ^ McDonald, J.H. "Myths of Human Genetics". Sparky House Publishing. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ Omotoso, Adeniyi & Medubi (2010), p. 244

- ^ Utah. "Observable Human Characteristics". Archived from the original on 2016-09-13. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ a b c Almaary et al. (2018), p. 23

- ^ KBC (1962), p. 281

- ^ Almaary et al. (2018), p. 24

- ^ KBC (1962), p. 281: "If it is a single dimple, then the big one is more common."

- ^ KBC (1962), p. 284

- ^ Omotoso, Adeniyi & Medubi (2010), p. 242

- ^ a b Almaary et al. (2018), p. 25

- ^ Almaary et al. (2018), p. 23: "Most of the people included in this study had the mesoprosopic facial form (132 (61.1%)..."

- ^ KBC (1962), p. 284, caption under Figure 6 photo: "Bisection of perpendicular line dropped from external canthus..."

- ^ Almaary et al. (2018), p. 22

- ^ Almaary et al. (2018), p. 22, 25: "We found that 54.8 percent of the total dimples [out of 336 individual dimples] were not positioned on the KBC point. [...] We observed a higher prevalence of dimples among the mesoprosopic group, compared to the other two groups, with no unilateral or bilateral predominence [sic]."

- ^ KBC (1962), p. 284

- ^ KBC (1962), p. 283-284; Almaary et al. (2018), p. 22

- ^ Almaary et al. (2018), p. 22: "Some believe that dimples make a person’s smile more memorable and distinct, associating it with cheerfulness."

- ^ KBC (1962), p. 281: "...it has come to be accepted [in Chinese culture] that a dimpled wife is one who brings happiness and good luck to the family."

- ^ Almaary et al. (2018), p. 22

- ^ a b "Face Reading Cheek Dimples". Your Chinese Astrology. Archived from the original on 2020-05-15. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "20 Delightful Dimple Quotes". enkiquotes.com. Archived from the original on 2020-05-15. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ de Lys, Claudia (1958). A Treasury of Superstitions. Philosophical Library. p. 99. OCLC 31114923.

- ^ Hartel, Richard W.; Hartel, AnnaKate (28 March 2014). "Junior Mints". Candy Bites: The Science of Sweets. New York: Springer Science & Business Media: 97. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-9383-9. ISBN 978-1-4614-9382-2. S2CID 199492484.

- ^ a b Steele, Richard. "On Laughter". The Tatler. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2020-05-15. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine (1866)

- ^ a b Williams, Michael (2013). "Shadows of Desire: War, Youth and Classical Vernacular". Film Stardom, Myth and Classicism: The Rise of Hollywood's Gods. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillian. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-230-35544-6.

- ^ "Advertising Section". Photoplay. No. April 1926. 1926. p. 142.

Positively dimples can lie made with the DOLLY DIMPLER, a simple harm-less device invented by a woman.

- ^ "Bizarro Beauty Products, from 1889 to Now | Collectors Weekly". Collector's Weekly. Archived from the original on 2020-05-23.

Modern Mechanix has uncovered several other disturbing 1930s and '40s beauty devices, including Isabella Gilbert's metal brace that could dig those smiley dimples right into your face...

- ^ "Bad Inventions: Dimple Maker – History By Zim". History by Zim. Archived from the original on 2020-05-23.

- ^ Hosie, Rachel (23 July 2017). "DIMPLEPLASTY: INCREASING NUMBER OF MILLENNIALS HAVING COSMETIC SURGERY TO CREATE DIMPLES". The Independent. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d Dunkling, Leslie (July 6, 2006). When Romeo Met Juliet. p. 68-69. ISBN 978-1412055437.

- ^ Montgomery, L. M. Anne of Green Gables. p. 248.

'Mrs. Allan has a lovely smile; she has such exquisite dimples in her cheeks. I wish I had dimples in my cheeks, Marilla. I'm not half so skinny as I was when I came here, but I have no dimples yet. If I had perhaps I could influence people for good...'

- ^ Gaskell, Elizabeth (1866). Wives and Daughters. p. 121.

- ^ Gone with the Wind (1936), p. 5–6: But she smiled when she spoke, consciously deepening her dimple and fluttering her bristly black lashes as swiftly as butterflies' wings. The boys were enchanted, as she had intended them to be, and they hastened to apologize for boring her.

- ^ Gone with the Wind (1936), p. 215: [Scarlett's] spirits rose, as always at the sight of her white skin and slanting green eyes, and she smiled to bring out her dimples.

- ^ Gone with the Wind (1936), p. 223: "Better stick to your own weapons—dimples, vases, and the like."

Research and literature cited

- Omotoso, GO; Adeniyi, PA; Medubi, LJ (2010). "Prevalence of facial dimples amongst South-western Nigerians: a case study of Ilorin, Kwara State of Nigeria". International Journal of Biomed Science. 6 (4): 241–244.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - "Dimples and Wrinkles". The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine. An Illustrated Journal, Combining Practical Information, Instruction, and Amusement. The Human Form Divine. 1: 304. 1866.

- Margaret Mitchell (1936). Gone with the Wind (1944 ed.). New York: The Macmillian Company.

- Boo-Chai, Khoo (1962). "The facial dimple—clinical study and operative technique". Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Transplant Bull. 30 (2): 281–288. doi:10.1097/00006534-196208000-00008. PMID 13871123. S2CID 5701728.

- Almaary, Hayaat F.; Scott, Cynthia; Karthik, Ramakrishnan (2018). "New Landmarks for the Surgical Creation of Dimples Based on Facial Form". The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology. 11 (5): 22–26. PMC 5955629. PMID 29785234.